WE of the Class of 1968 are gathered here today in order that we may properly take leave of Dartmouth College. Dressed in the gowns of tradition, we will cross the platform to collect our certificates of success. Then, having completed the rites of passage, we will go our many separate ways. What has been Dartmouth College will be for us memories of road trips and snowball fights, Winter Carnivals and term papers, visits from George Wallace and Stokely Carmichael. These and other memories will stay with us, as we live and act in a larger society.

But it seems to me that there is a paradoxical element in the education we have received at Dartmouth. Through our highly qualified faculty and our fine facilities, we have been given the opportunity to develop our minds and stock them with funds of knowledge. Yet our location in the wilderness, for all its virtues, may have shielded us from some of the main currents of life in our society. I would suggest that our liberal education, in the absence of a prolonged confrontation with social reality, may suffer from a serious inadequacy: it may obscure a vital link between our knowledge and its relevance to the world beyond Dartmouth College. I am grateful for the rise in student activism at Dartmouth, for our Tucker Foundation projects and our Foreign Study Program — and for the New Hampshire primary. It is through such channels as these that we "monastic" Dartmouth men can translate knowledge into action.

It is traditional for a valedictory speaker to talk of the mingled nostalgia, exhilaration, and apprehension he and his fellow graduates experience as they anticipate crossing the threshold into the larger society. A Dartmouth man should look forward to a full life in his post-college years. He should expect to do graduate work or get a promising job, see lots of women and, maybe, travel abroad for a while. Then he may raise a family and settle down in a comfortable suburban home with a three-car garage and a little place out back where he can protect his motor boat from the snows of winter. Such expectations may have been realistic once, but for most of us in the Class of 1968 they are daydreams.

They are daydreams because the larger society we will enter is in turmoil. For us, the act of commencement is tainted with a nightmare vision of smoking cities policed by soldiers, of silent factories, and of empty stores. These are our own American cities we envision, and they are the cities of the people whom we have made the victims of our "protection" abroad. Our powerful, complex American society trembles before the threat that the cancerous injustices it has tolerated so long may now destroy it from within. We who graduate today are the citizens who must resolve the injustices of the nation we shall inherit. We shall also be called to wear the khaki of the soldier who puts his airborne torch to foreign cities; cities he is told to destroy in order that they may be saved. We fool ourselves if we think we can build our own society and destroy a foreign nation at the same time.

Of the many pressing domestic needs we face, I believe it is most crucial that we respond to the needs of our oppressed black, tan, and red minorities. Having suffered intolerably under the burden of discrimination, they are now prepared to thrust it from their shoulders. We white elite may make that difficult for them, or we may lend our shoulders to the burden and help to cast it away — but with us or in spite of us, it will be gotten rid of.

Let us be clear that we must either promote or oppose this process, but we cannot be neutral. There is no option of non-involvement today. All of us, regardless of the colors of our skins, are constituent elements of the established society that has institutionalized oppression. Those of you who are non-whites know this with the certainty of experience, and you are acting accordingly. We who are white must also realize that to evade the responsibility of reform is to passively aggravate the conditions that must be transformed if this society is to be worth living in. In the words of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders:

Segregation and poverty have created in the racial ghetto a destructive environment totally unknown to most white Americans.

What white Americans have never fully understood — but what the Negro can never forget — is that white society is deeply implicated in the ghetto. White institutions created it, white institutions maintain it, and white society condones it.

Surely it must be apparent to us, as highly educated people, that the domestic problems we face today are of compelling urgency. They are radically different from the problems faced by past generations of Americans, and so they demand radically new solutions — solutions that aim at their roots. Had our nation adopted the programs urged by students of minority group relations forty years ago — and those programs were radical in their day — we might now be graduating into a very different society. I quote again from the report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders:

This is our basic conclusion: Our nation is moving toward two societies, one black, one white — separate and unequal.

To pursue our present course will involve the continuing polarization of the American community and, ultimately, the destruction of basic democratic values.

The alternative ... is the realization of common opportunities for all within a single society.

This alternative will require a commitment to national action — compassionate, massive and sustained, backed by the resources of the most powerful and the richest nation on this earth. From every American it will require new attitudes, new understanding, and, above all, new will.

There is no question but that America has at her disposal the material and financial resources that a national commitment to the goals of social justice would require. We here can bring our educated minds, our youthful energy, and our determined wills to the endeavor. We can transform our society, but we can do so only if we are able to stop the present destructive mischanneling of our talents, our resources, and ourselves. The national effort for which we and others of our age are manipulated makes "niggers" of us all, regardless of the colors of our skins. I refer, of course, to the Asian war that has begun in Vietnam.

Most of us who graduate today will find that our career plans, our graduate educations, and our attempts to respond to the needs of this nation will be interrupted by a notice to report for induction into the Armed Forces of this country. Many of those drafted will be ordered to join in the military effort in Asia. I urge you to make the fullest use of the academic skills you have gained at Dartmouth College before you accept that governmental imperative. Study the history of the Vietnam war, and study its conduct. Study the impact it is having on Asian societies, on Asian attitudes toward America, and on America's conception of herself. Men of the Class of 1968, educated men, Dartmouth men, before you set off to participate in the devastation of that small country, Vietnam, and to risk your lives into the bargain, consider what you are about.

As you study this war I believe you will become convinced, as I am convinced, that it is more than an accident, or a freak accumulation of mistakes. It is the inevitable fruit of an international policy aimed at maintaining an oppressive status quo. It is my conclusion that the Vietnam war is a colossal stupidity, a vast international atrocity, and an expensive lesson in the futility of modern aggressive imperialism — for, thank God, we are losing that war. The battles we claim to be winning have moved from the countryside to Saigon itself, where we feel forced to "protect" the people by firing rockets and cannons at their homes.

These are sad, shocking things to say, and I do not say them lightly. I say them in the spirit of President John Sloan Dickey's 1961 Convocation Address. The President said on that occasion that "we must reckon with the fact that it will not profit America to 'win' any struggle if thereby as a nation we lost our character, or as the Bible would put it, our soul," and he expressed his conviction that an American "success" in the Bay of Pigs invasion would have been a great tragedy for this nation.

Before you answer the call to fight, think well of what this war means for America. It underscores the words our honored alumnus, Daniel Webster, spoke in 1811: . . a free government, with an uncontrolled power of military conscription, is a solecism, at once the most ridiculous and abominable that ever entered into the head of man." Begun and maintained on a platform of official falsehood, the war has taught us to speak cynically of a "credibility gap" between ourselves and the men who by tradition and by law should represent us honestly and honestly inform us of their actions. It drains from our land the wealth that should provide hospitals, schools, and homes, making a farce of progressive domestic legislation. In truth, the short-range profits that derive from a wartime economy are deceptively attractive, for in the long run a society pays dearly for its investments in wars.

Men of the Class of 1968, educated men, Dartmouth men, use the skills that you have gained here as you plan your courses of action. We must find our places in an on-going universal struggle for freedom and human dignity. I urge you to refuse to fight in Vietnam when that call comes to you. Take the path that seems appropriate for you. It may be conscientious objection, draft resistance, or escape to a country of greater freedom in the north. Those of you in ROTC and those of you who believe we must maintain a standing army for defense may face the much more difficult path of refusing to comply with an order to go to Vietnam. But whatever you do, I pray that you will not sacrifice your minds and your bodies in the service of this ignoble cause.

My friends, we cannot win hearts and minds through brutal coercion, nor can we hide the ugly sight of social injustice beneath a wave of uniforms. The society we seek at home and the cooperative world we must have can come only through the commitment of our talents and our resources to the tasks of peaceful, constructive change. We must make that commitment our own.

Valedictorian James Newton, summa cumlaude graduate with highest distinctionin psychology, received four outside graduatefellowships but as a Quaker hopesto spend two years with the AmericanFriends Service. Centering his interestsin international relations programs atDartmouth, he was active in the CutterHall Experiment and Cosmopolitan Cluband studied abroad in his junior year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNon-Violent Change in Our Society

July 1968 By THE HON. JACOB K. JAVITS, LL.D. '68 -

Feature

Feature"People as Well as Things"

July 1968 By HARVEY P. HOOD '18 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1968 -

Feature

FeatureReunion Week: Fun Plus Education

July 1968 -

Feature

FeatureCouncil Honors Three Alumni

July 1968 -

Feature

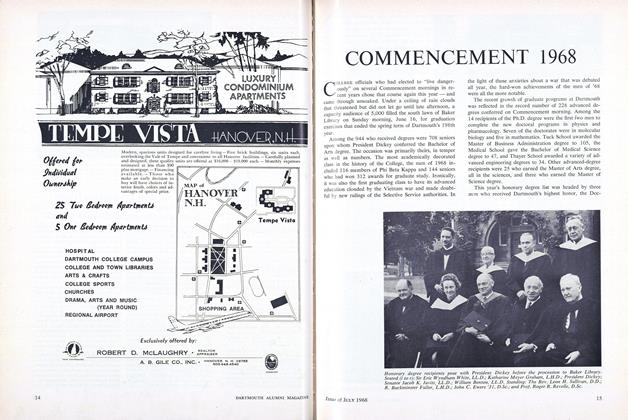

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1968

July 1968

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1956 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Better Understanding

Mar/Apr 2007 By ANDREA USEEM ’95 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLouis Burkot

OCTOBER 1997 By Jon Douglas '92 -

Feature

FeatureAre Conservatives Being Silenced?

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCox, Poe, and Jefferson's Dead Body

MARCH 1995 By Peter Gilbert '76 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Up

SEPTEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham