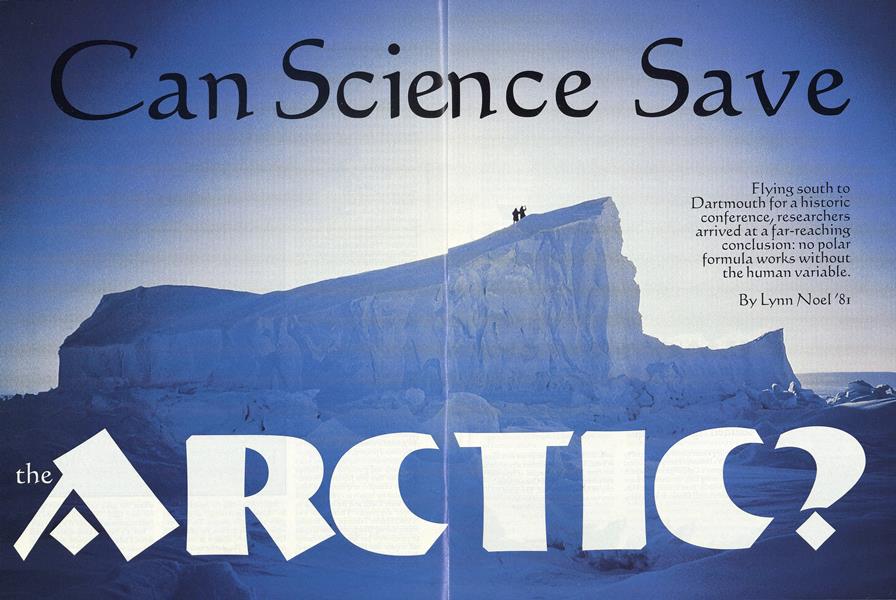

THE HANOVER PLAIN is a far cry from the North Pole—until it snows. But in the high blue days of early December, with a fresh fall of snow squeaking underfoot and icicles tinseling bike handlebars, 250 Arctic scientists seemed right at home.

Attending a joint meeting sponsored by Dartmouth's Institute of Arctic Studies and the U.S. Army's Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab, the scientists came from Yellowknife, from Iqaluit, from Oslo and Stockholm and Helsinki, from Moscow and Beijing, from Nuuk, Reykjavik, and Rovaniemi. Europeans were there in force, 35 Russian scientists arrived on a bus from JFK, and a handful of Japanese and a delegation from the Chinese Academy of Sciences showed. The occasion was a defining moment for Arctic research, possibly the mostimportant scientific gathering for the North since the International Polar Year of 1882-83.

It was the first International Conference for Arctic Research Planning, designed to promote international cooperation for science and policy research in the far North. The catalyst is a five-year-old International Arctic Science Committee whose U.S. delegate and vice president is Dartmouth professor oran Young. Since 1989 Young has directed the College's Institute of Arctic Studies within the John Sloan Dickey Center for International Understanding. A political scientist with a lifetime involvement in the high North and an intellect that crosscuts many disciplines, Young has drawn together social and physical scientists, lawyers, doctors, historians, writers, and even artists.

This is not the first time polar scientists have gone south to Dartmouth in the winter; Dartmouth hosted a polar-research conference in December 1958. Maybe the difference this time is the public's sense of urgency. The Arctic has become a focus of environmental concern. Consider:

•Toxic clouds from the Chernobyl explosion.

•Soviet nuclear submarines corroding on the sea bed, including some with radiation-packed warheads.

•Hydroelectric dams that flood whole watersheds.

•Polar bear and seal hunts and protests that pit local hunters against animal-rights activists.

•Oil-slicked otters from the Exxon Valdez and Soviet pipelines that leak crude oil into the Siberian tundra.

•Cod moratoriums, whaling bans, highseas face-offs over salmon, and farming schemes for everything from lobsters to sea urchins.

•Massive clearcutting of old-growth forests in the taiga—the great green belt of northern forest that girdles the Pole from Vermont's Northeast Kingdom to Clayoquot Sound in British Columbia and most of central Siberia.

•Smog warnings in Fairbanks from Arctic haze, and sunburns from a growing ozone hole.

•Mercury pollution in the food chains of northern Quebec, and methane gas released by flooded river basins.

•Proposed drilling leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge that draw international fire from environmentalists and native groups.

•Low-level military-training flights over Labrador that disturb caribou migrations and native settlements.

•Unemployment, alcoholism, suicide, drags, and a profound sense of loss in tiny northern communities.

•Home rule in Greenland, self-government in Canada's Nunavut, separatism in Quebec, and the collapse of the Soviet Union, all remapping the balance of power in the North.

Yet, despite the barrage of depressing television news, the region remains largely unexplored. "We know less about the Arctic than we do about the dark side of the moon," says U.S. Navy officer and conference delegate Robert Anderson, whose submarines carry at least one payload per year of scientific equipment into the North Pole beneath the sea. The Arctic's unknown quality makes it a test case for the world: it is the planet's last large relatively undisturbed ecosystem that has any significant history of human use.

While "preserve biodiversity" is a rallying cry for tropical ecosystems, an Arctic slogan might be "preserve biodensity." There are relatively few species of animals in the far north, but those species are represented in great numbers of individuals. These large concentrations of wildlife are vulnerable to catastrophe. The world's last great auk was slaughtered on Newfoundland's Funk Islands—named for the smell, or "funk," created by the seemingly infinite mass of colonial seabirds and later by their rotting carcasses. The auk serves as a symbol of the Arctic's vastness and concentration of riches, its apparent infinity and all-too-real vulnerability.

Unlike Antarctica—a nationless continent shared under international treaty since 1959—the Arctic is a chilly Mediterranean, an ice-covered ocean rimmed by eight sovereign nations. Canada, the United States, Russia, Finland, Sweden, Norway, Iceland, and Denmark all have well-established national territorial claims. More than 90 percent of the Arctic is in government ownership, and each nation exercises its rights to "exclusive economic zones" in its slice of the Arctic pie.

Another polar difference: Arctic climate is controlled not by a static land mass, as at the South Pole, but by gyres of wind and water in constant motion. Upwelling currents from the sea bed create open oases of nutrient-rich water, called polynyas, which draw huge concentrations of algae, plankton, fish, and the seabirds and marine mammals that feed on them. Snow piles on snow in the mountains of the Arctic rim, compressing ice crystals into giants' tongues of glaciers that calve off the icebergs of Glacier Bay and Greenland's Iceberg Alley.

Most importantly, the region of the North Pole is populated not by penguins but by people. Institute for Arctic Studies Senior Fellow Gail Osherenko studies the effects of changing policies on northern peoples and cultures. For the Dartmouth conference Osherenko dressed in a felttrimmed vest of domesticated reindeer and exhibited photos of Nenets reindeer herders on Russia's Yamal Peninsula. Oneseventh of their pasture land has been hurt by oil and gas development—a total of 17 million acres damaged or destroyed. The Russians have not yet introduced any plan to recognize the natives' rights to their ancestral land or even include them in decisions over it. What's worse, this kind of dispossession is common.

Nonetheless, the Dartmouth conference's chief conclusion is that people determine the fate of the Arctic, and science that excludes people will fail to save the region. Research must take human impacts into account for both practical and ethical reasons. Ecologically disturbed areas make up 8.3 percent of the Russian Arctic, ac according to biologist Arkady Tishkov of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He reported that every American dollar or its equivalent invested in oil and gas in the region results in four to eight square meters of disturbed tundra. Scottish scientist Robert Crawford said scientists have a moral obligation to mitigate such change and not just to study it. "If you do not address the issues of ecosystem disturbance," he argued, "you risk being accused of using the Arctic as a great international scientific playground."

Oran Young and anthropologist Nicholas Flanders, associate director of Dartmouth's Institute of Arctic Studies and president of the Arctic Research Consortium of the United States, have risen to that challenge in their own work to explore alternatives for the West Greenland salmon fishery. The collapse of fisheries is among the North's highest-profile issues today, and it is a critical one for the United States. In 1989,40 percent of the total American fish harvest came from Alaskan waters; it netted $2 billion for 50,000 people. From 1988 to 1992, the value of the West Greenland catch dropped by two-thirds, according to Young and Flanders. Research plans arising from the conference seek a more sophisticated understanding of the human and non-human interactions that can cause such collapse—from overfishing, quotas, and net size to water temperature, habitat loss, and climate change.

The Arctic's exploitable resources, which far exceed local markets, are under the demand as well as the control of the superpowers. As much as 600 trillion cubic feet of natural gas, 90 percent of the former Soviet Union's reserves, lie beneath northwestern Siberia. Reserves of northern crude oil total 100 billion barrelssome geologists double that estimate. The Trans-Alaska Pipeline fuels 24 percent of American oil production. A week before the conference, the United States lifted a longstanding ban on Alaskan oil exports.

Fossil fuels are not the only source of Arctic energy. Electric rivers pour into Arctic seas. Most of Scandinavia's rivers are already dammed, and the controversial James Bay project has powered Canadian and American energy grids—as well as electrifying Quebec separatism, environmental opposition, and native self-determination. Russia has outstripped even Quebec in promoting hydro power from its vast chunk of the Arctic.

Mining in the North balances on the thin edge of technology and market prices.

The Arctic is a treasure chest of copper, zinc, tin, nickel, and lead—not to mention gold, silver, and Siberian diamonds—but it is a well-locked chest. Extreme conditions and sheer distance make minerals costly to extract. Hard-rock mining comes with such baggage as ugly pits and toxic tailings, making it less than popular among environmentalists.

The Arctic is also as valuable for where it is as for what it holds. A glance at the globe shows that the far North is a shortcut between East and West. Russian nuclear icebreakers can now keep the Northern Sea Route open as many as 150 days a year, and there is serious interest in opening the Northwest Passage for shipping between Europe and Japan. This is a hot-button issue for Canadians, who are understandably nervous about the hazard of oil spills and who claim the waters of the Arctic archipelago within their exclusive economic zone.

Despite these global-sized resources, the world powers alone cannot determine the Arctic's ultimate fate. The people who live there remain crucial to far-northern realities. "We recognize the increasing northward flow of power and funding, brokered through northern communities in this age of new political realities for native peoples," stated Milton Freeman, a professor of anthropology at the University of Alberta. "We must develop the economic and political linkages of indigenous societies to nation-state transnational orders," added Rasmus Ole Rasmussen, a Danish geographer who co-chaired a conference working group on the environmental and social effects of Arctic industrialization.

The interaction between humans and wildlife is especially compelling. The Porcupine caribou herd provides an entire way of life to Canadian and Alaskan Gwich'in, who vigorously oppose drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. In Russia, wild reindeer compete with domesticated herds, and their herders, for pasturage and migration routes. International treaties protect many migratory species—such as polar bears, whales, and seabirds—but conflicts among native subsistence, economic development, and preservationists can shift and crack alliances faster than sea ice in summer.

Much of what we know about the Arctic, however, stems not from economics but from warfareCold Warfare, coincidentally. Considerable Soviet-American rivalry centered in the sliver of Arctic space that separated the powers. Washington had an urgent reason for northern military and scientific initiatives: Russia already had hundreds of thousands of people living in the Arctic, and its infrastructure of roads, settlements, and ports made the Soviets seem much more capable than NATO of sustained high-latitude warfare. The United States had to catch up to develop cold-worthy personnel and materiel. It was in that desperate spirit that Dartmouth's Northern Studies Program got its start in 1953.

As the Cold War's thawing has changed Arctic policy, it has reshaped the goals of Arctic study as well. What is needed, Osherenko and Young write in their book TheAge of the Arctic, "is new intellectual capital to cope with Arctic issues in an efficient, equitable, and ecologically sound fashion, in contrast to additional efforts to recruit new members to swell the ranks of the various interest groups engaged in the struggle." The Institute's Stefansson Fellowship, established in 1990, invests such intellectual capital in Dartmouth undergraduates, sending them to Russia, Alaska, Greenland, and Canada for Arctic studies.

The New World Order has also seen the rise of indigenous peoples and self-government. Native organizations like the Inuit Circumpolar Conference, the Dene Nation, and the Sami Council have strengthened claims over the right to manage tribal lands across the boundaries of nation-states. The disbanding of the Soviet Union poses disturbing parallels for its next largest neighbor, Canada, now coping with a restless Quebec and the impending self-government of Nunavut, the eastern half of the Northwest Territories. Federal governments cannot afford to manage the lands that they own, and the Arctic often takes low priority on the budget-cutting table. The map of the region, in short, is being re-drawn. Researchers can no longer afford to operate in a policy vacuum, according to Bruce Rigby, a former Parks Canada chief who now works for the Nunavut Research Institute. Local communities "will play an extreme role" in funding research world- wide, he told fellow Dartmouth conferees.

T o create an "enlightened plan for human activity in the Arctic," Oran Young says, you first need a new mental map that "breaks the iron grip of the Mercator projection." You need to stare down at the planet from the top—put the Arctic in the center, not at the edge. Then die connections among the region become selfevident. The shift toward sustainable development in the Arctic, as in any region, has two cornerstones: First, natural systems and their limits cannot be separated from human activity. Second, cultural systems that value non-material resources must be promoted and respected. The conference used these lodestones to sketch out new directions on that mental map. Studies of global ecosystems, of life at the edge, and of societies undergoing rapid cultural change teach us about the relationship of humans to the earth.

Geographers know this instinctively. As Dartmouth professor Robert Huke '48 says, "Geography is the study of the earth as the home of human beings." As such it straddles both "social science" and "natural science." (That conflict is a big reason why geography has been booted out of every Ivy League school but Dartmouth.) When the issue gets extended to the cross-disciplinary study of the Arctic, things get even more complicated: researchers must blend not just social and physical science but also "pure" knowledge with the practical. "Some research is funded to mask the effects of pollution. Often, it's not more science that's needed at all, but more political activity," said Scotland's Robert Crawford.

Crawford, in fact, disparaged the hope that science can ever restore the Arctic to pristine condition. He reported that his fellow committee members laughed that notion right out of the room. "And they were quite right," he added. "The whole notion of recovery is a cosmetic pseudo-science."

Oran Young agrees that pure science is not the sole answer. "We need to add a new criterion of relevance, while maintaining the requirement for excellence, in science," Young said at the conference. "We must stress the importance of integrating natural and social science to gain a holistic understanding of real-world problems.

It is clear from the conference at Dartmouth that good Arctic science will involve human knowledge of all kinds and applications—from ice cores to elders' tales to research projects designed by native communities. And so, if science has anything to do with saving the Arctic, it must return to its ancient intellectual roots. The pure and the practical, the traditional and the modern, the quantitative and the experiential, the economic and the aesthetic must merge for the future of this home for human beings.

Flying south to Dartmouth for a historic conference, researchers arrived at a far-reaching conclusion: no polar formula works without the human variable.

A humpback whale sounds in Alaska. Concentrations of Arctic wildlife make them vulnerble to catastrophe.

The Northern Lights hum over Denali National Park.

Arsenic and old ice: explorer Hall.

A Chukchi reindeer herder in Siberia. The Russians have yet to recognize the natives' rights to their land.

Tuthill hills at his job.

Arctic Lines The Arctic Circle lies at 66° 30' north latitude. Reckoning by the midnight sun, that is the southern limit of the 24-hour summer day. But reckoning by the treeline, the Arctic tundra meanders south of the circle. Some experts define the region by isotherms that connect points where the average annual temperature is 25 degrees Fahrenheit or where the annual high is 50. Other experts define the Arctic as the region where Inuit live. The Inuit, in turn, are defined as native peoples who live in the Arctic—a nice bit of circumpolar logic.

A Showman's Images Dartmouth's polar reputation stems in part from Vilhjalmur Stefansson, a prominent Arctic explorer early in this century. In 1952 he moved to Dartmouth with his 20,000 books, 20,000 pamphlets, and a vast array of manuscripts that constitutes one of the premier collections in North America. A dynamo behind the podium, Stefansson supplemented his lectures

with visuals—300 hand-tinted lantern slides. Dartmouth has them all, among the 20,000 Stefansson photographs in Baker Library's Special Collections. The dogsled shot on the opposite page is one of Stefansson's.

Art you Fit to be an Arctic Explorer? Stefansson devised a sim pie test for Arctic wannabees in the Army Air Corps: If your hands go numb when washed in cold tap water, stay home.

Better than Cashmere Stefansson was impressed with the fine wool of the oomingmak, or Arctic musk ox—a long-haired cross between a bison and a sheep. Eight times warmer than sheep's wool, musk-ox fibers are among the toastiest on earth. Stef suggested that the musk ox could be domesticated for its wool, which naturally sheds each spring. Anthropologist and ecologist John Teal Jr. '42 took up Stef's idea as a means of income for the Inuit. Since musk oxen make a formidable protective circle around their calves on land, Teal rounded them up by catching them off guard in water. Diving into 35-degree lakes, he searched underwater for the shortest-legged calves. He tried raising them in Vermont (too hot), then moved them to the University of Alaska in 1964. The experiment worked. Today the herd, still the only domesticated one in the world, keeps more than 200 Inuit knitting. Check out their cooperative, called Oomingmak, on the World Wide Web at .

Don't Leave Nome Without It In 1944 Vilhjalmur Stefansson wrote an Arctic Manual for the Army Air Corps. The 550-page volume had advice on everything from airplanes (park them facing the prevailing wind, he advised) to zippers (avoid them). Here are some Do's and Don'ts based on Stef's manual. Do: Use the skin of a baby caribou for your underwear. Skins from older animals are too warm—unless you happen to be flying in an open-cockpit plane. Wear eye protection to prevent snow blindness. Dark glasses are okay, but they frost over. Eskimo goggles made of wood with slits don't frost over, but also have a drawback "The field of vision is so limited that you cannot, without stooping over, see what lies at your feet." Sleep naked. Perspiration condenses on underwear and can freeze. Eat the head when moose or caribou is on the menu—the best part is behind the eyes. Roast it over an open fire by stringing it through the nostrils. Avoid rice, oatmeal, and beans. They take too much time and fuel to cook. Stick your feet in a snow bank if you break through the ice. Cold, dry snow acts as blotter. Don't: Lie down on pack ice. A polar bear may mistake you for a seal and pounce.

Don't: Eat your friends, unless you have already consumed your underwear. "Before the extremity of cannibalism is reached, all articles made out of rawhide or hide that has not been commercially tanned can be used as food," says Stef's manual. Use dogs as guides. "It may be fatal, for it has been recorded that parties following dogs have passed within a hundred yards of camps without noticing it." Camp leeward of the prevailing wind. Lees gather snow in open country. Overcook your food. Scurvy can result.

The Reviews Will be Glowing Every Dartmouth grad knows that the North Pole's second-most-famous denizen, a flight-worthy luminary named Rudolph, was first revealed to the world by Robert May '26. Now Robert Sullivan '75 has written an elaborate study of the true nature of reindeer flight and of Santa's Arctic headquarters. George Bush and Edmund Hillary cooperated with Sullivan's research. So did Dartmouth Special Collections Library Philip Cronenwett and Arctic Institute Director Oran Young. The Stefansson Collection came into play, and Photographer Mehling '69 clocked the speed of Santa's sleigh as it passed over Dartmouth Hall. The resulting book, entitled Flight of the Reindeer: The True Story of Santa's Mission, is due out by Macmillan this fall.

Noisy Lights The aurora borealis, nature's most beautiful plasma laboratory, is a loud place. The electrons that spark the lights also interfere with high-frequency radio waves and disrupt radar and satellite transmissions. In 1953 the navy asked Thayer professor Millett Morgan to help solve the problem, known as auroral roar. Today physics professor James Labelle's rocket- and ground-based measurements of the ionosphere are revealing fine structures within the ruckus. The sound is like a high-frequency chorus, says Labelle.

Wow, That's Strong Coffee In 1871, while leading a U.S. government expedition to the North Pole, Arctic explorer Charles Francis Hall died in northern Greenland's icebound Thank God Harbor. Hall had sickened after drinking a cup of coffee; a navy investigation concluded that he died of natural causes. More than half a century later, Vilhjalmur Stefansson suggested foul play to his colleagues at Dartmouth including peripatetic English professor Chauncey Loomis. In 1968 Loomis

mounted an expedition to Hall's lonely grave, exhumed the body, and arranged for bits of hair and nails to be tested in a Toronto forensics lab. It found high concentrations of arsenic. Hall may have accidentally overdosed on tranquilizers that contained the chemical. A darker explanation: his restive crew may have slipped rat poison into his coffee. Loomis published an account entitled Weird and Tragic Shores.

The Coldest Place in Hanover On a 90-degree August day, Andy Tuthill '76 dresses for work in mittens and down parka. While the campus swelters, Tuthill—a hydraulic engineer with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers' Cold Regions Research and Engineering Lab—works in a large sub-freezing room to test a model of a problematic ice dam on the Illinois Waterway. CRREL is one of the country's top research facilities for just about anything frigid. With its 24 cold rooms—some capable of 50 degrees below zero— CRREL has become an international ice library, storing ice cores that hold samples of the earth's climate and atmosphere dating back as far as 250,000 years. Dartmouth and CRREL share facilities and 16 senior researchers. About half of the research aims to support sup-port the cold-weather soldier with ice runways, powerful plows, and super-sticky snow tires. Civil engineering and polar science make up the other half of the research. CRREL's ice engineers work to reduce ice buildup in dams or rivers, foster avalanche control, improve asphalt and concrete for safer cold-weather roads, and prevent ice buildup on power lines. The lab offers public tours during the summer on Tuesdays and Thursdays, and by appointment throughout the year to interested groups. If you're in Hanover on a hot day, be sure to request an in-depth tour of the cold rooms.

Top of the World Flying from Fairbanks, Alaska, on September 5, army major Dick Lougee'27 became the first Dartmouth grad to reach the North Pole.

LYNN NOEL '81 is a research fellow at theInstitute of Arctic Studies and the author of Voyages: Canada's Heritage Rivers.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's Productivity

March 1996 By James Wright -

Feature

FeatureThe Left Fielder's Glove

March 1996 By JOHN MONAHAN -

Feature

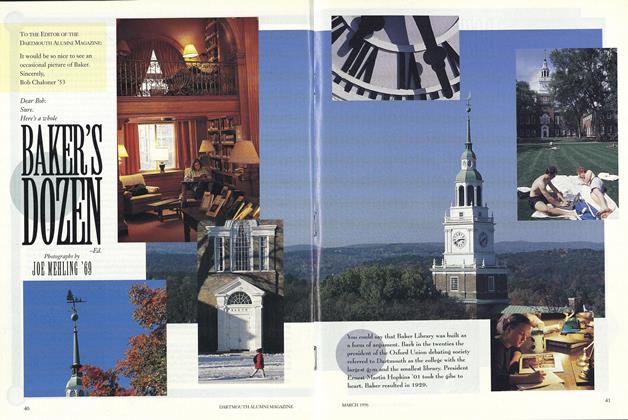

FeatureBAKER'S DOZEN

March 1996 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

March 1996 By "E. Wheelock" -

Article

ArticleSpace Politics

March 1996 By Karen Endicott -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

March 1996 By Armanda Iorio

Features

-

Feature

FeatureALUMNI COLLEGE '65

MAY 1965 -

Feature

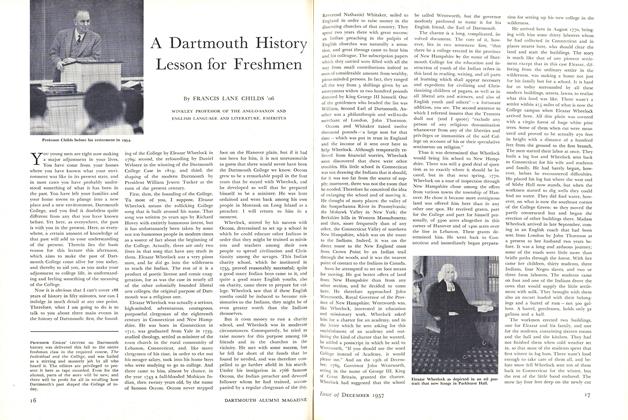

FeatureOldest Living Graduate, Will Be 100 This Month

APRIL 1964 By Dr. Edwin H. Allen '85 -

Feature

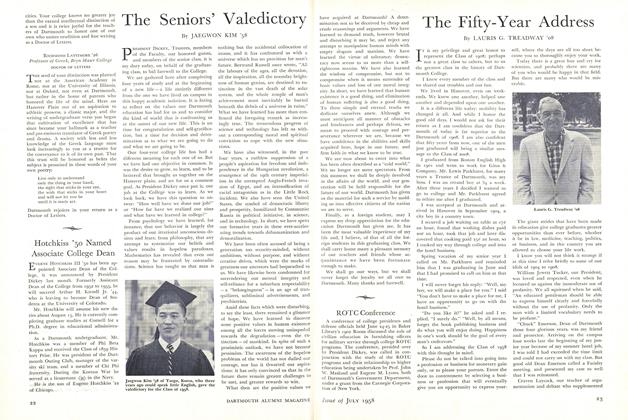

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1958 By JAEGWON KIM '58 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Innovative Economist

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2021 By MIKE SWIFT