A fabulously lucrative business career to support the already fascinating but very costly hobby of Egyptology . . .

A neat ambition, but not one likely to succeed in the Depression world into which RICHARD A. PARKER '30 and his classmates graduated. Four years later, still in the same job—though admittedly lucky to have one—Parker started doctoral studies at the University of Chicago and went on to become one of the world's leading Egyptologists.

From 1949 until his retirement this year as Egyptology chairman at Brown University, he headed the only independent department in his field in the U.S. His scholarship has enriched the knowledge of the ancient world through extensive publication, notably the four volumes of Egyptian Astronomical Texts, done in collaboration with Otto Neugebauer, a mathematical historian at Brown. The series is a compilation of all known texts of early decans, stars used to measure time, found as far back as 2150 B.C. on coffin lids; star clocks from the tombs of 12-century Ramses; and other astronomical inscriptions. He is a Corresponding Fellow of the British Academy, an illustrious body comprising only 123 members in 30 countries, only one of them an American Egyptologist.

Egyptologists come in essentially two models, Parker explains: archeologists and philologists, those who deal with artifacts and those whose main concern is language—"although both approaches become history." He is a philologist, an epigrapher, who deciphers and interprets the inscriptions and papyri uncovered by the archeologists.

Egypt is a fertile field for the historian for two fortuitous reasons. Models for 20th-century bureaucrats, ancient Egyptians were record-mad, and—thanks to a hot, dry climate—their documents dating back to 3000 B.C. have been found in a remarkable state of preservation.

The Brown Department of Egyptology is unique in more than one respect. For 23 years Parker has been that rarest of academic phenomena, an administrator with no financial worries. "I was the only chairman the provost greeted with a smile at budget time," he remarks cheerfully.

The department and its handsome endowment are an indirect legacy of an unsavory chapter of American history. C.E. Wilbour, an 1854 Brown alumnus, was a minor factotum of Boss Tweed of New York infamy. When the larcenous ring was broken up, Wilbour made a precipitate retreat to Europe, presumably with some share of an estimated $45 million bilked from the city. In later years, indulging a long-standing hobby in affluent leisure, he became a respected Egyptologist. During the 1920's a daughter, piqued at the handling of some family treasures, withdrew her support of the Brooklyn Museum and, at her death, bestowed a considerable fortune on Brown to establish a department to honor her father's memory.

When the Wilbour windfall came in 1947, Brown's president instructed Neugebauer to "find me an Egyptologist." Parker, then teaching at Chicago and already working with Neugebauer, was an obvious choice. He was hesitant to relinquish a recent appointment as field director of Chicago's permanent expedition at Luxor in the Nile "Valley of the Tombs of Kings," where he had spent part of several years, but he finally yielded to the unprecedented opportunity.

The Egyptologist is a rara avis. By Parker's estimate, there are no more than 18 to 20 professionals in America, including both university scholars and museum curators. A problem at Brown has been to choose top-flight graduate students willing to risk four years of their lives on a field which might or might not support them after they earned their doctorates.

Parker tells a wry story to illustrate the scarcity of openings in the trade. On a recent trip to England, he was riding in a small car with the Oxford Professor of Egyptology and another distinguished colleague when they had a near miss from a truck. The Englishman's first breathless comment: "For a moment there, I thought there might be three vacancies in Egyptology."

Queried occasionally on the justification for large expenditures on such an esoteric subject, Parker likens the study of the ancient world to a medical history. More than pure challenge—"Just because it's there, like Everest"— Egyptology "deals with the human animal, with mankind as a unit. It is just as important to know what man thought in the past, how he met crises, how he adapted, as it is for a doctor to know his patient's health record. It gives us background against which to judge ourselves."

Retirement from Brown has meant little slackening in Parker's scholarly pace. His research continues wherever there are important Egyptian collections. He was in London in the spring for the commemoration of the opening of King Tut-amkh-amoun's tomb in 1922. He returns next month to speak at a two-day symposium on ancient astronomy sponsored jointly by the Academy and the Royal Society.

In his extensive collection of cartoons spoofing Egyptology, his favorite has one portly gentleman remarking to another: "I'm in Egyptology; what's your racket?" With a racket like Richard Parker's, who needs hobbies?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe U.S.-Canadian Relationship

December 1972 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29 -

Feature

FeatureHall of Hallmark

December 1972 -

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Hold Annual Meeting

December 1972 -

Feature

FeatureRugby Posts A Winning Fall Season

December 1972 By TREVOR O'NEILL '73 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

December 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1972 By Jack DeGange

MARY ROSS

-

Feature

FeatureOMBUDSMAN

OCTOBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Article

ArticleTriple-Threat Academician

DECEMBER 1971 By MARY ROSS -

Article

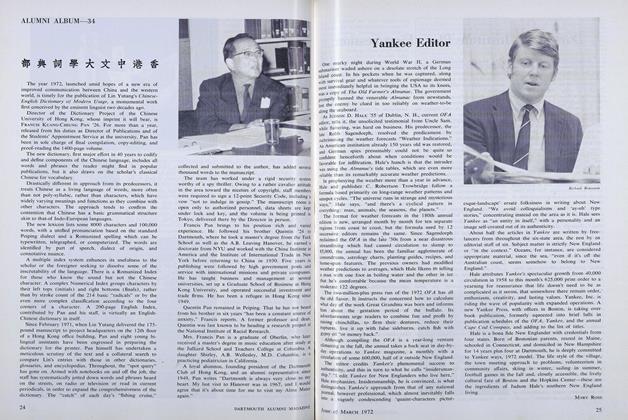

ArticleYankee Editor

MARCH 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureGiving and Getting

December 1979 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureLiberal Arts, yes 'Core of Knowledge,' no Changing the Calendar, maybe

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Mary Ross -

Article

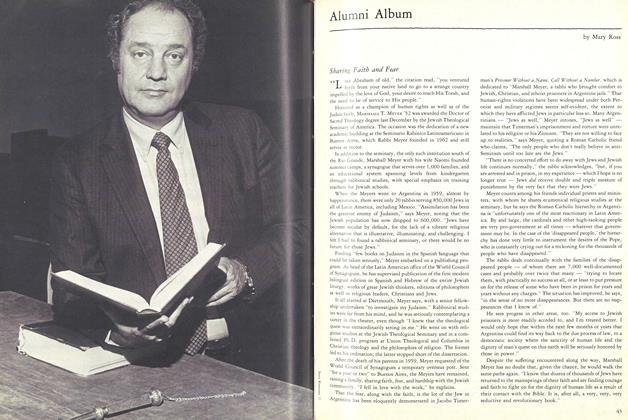

ArticleSharing Faith and Fear

MAY 1982 By Mary Ross

Features

-

Feature

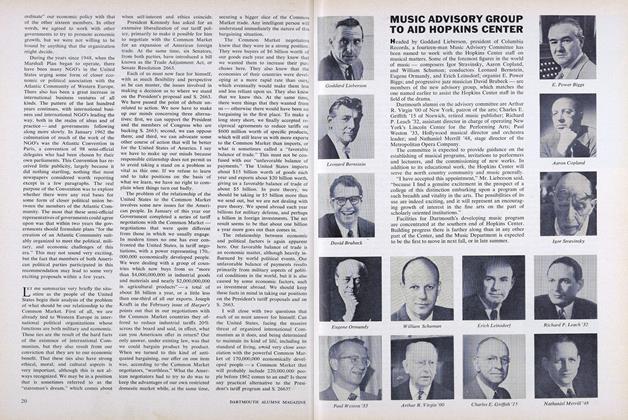

FeatureMUSIC ADVISORY GROUP TO AID HOPKINS CENTER

May 1962 -

Feature

FeatureAIMEE BAHNG

Nov - Dec -

Feature

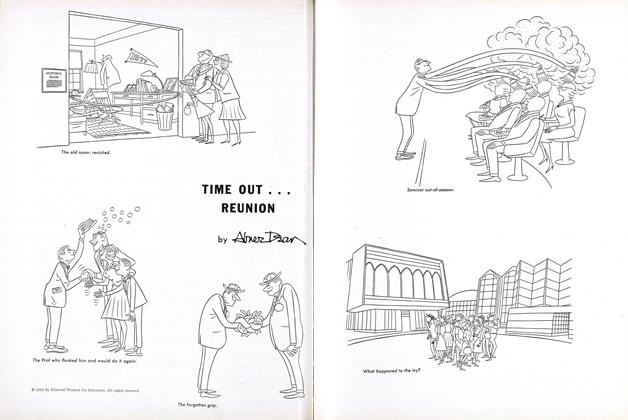

FeatureTIME OUT ... REUNION

JUNE 1963 By Abnez Dean -

Feature

FeatureTHE MOCK-DUEL MURDER

April 1956 By EDWARD CONNERY LATHEM '51 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

JAnuAry | FebruAry By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

FeatureManin the Red Flannel shirt

January 1974 By M.B.R.