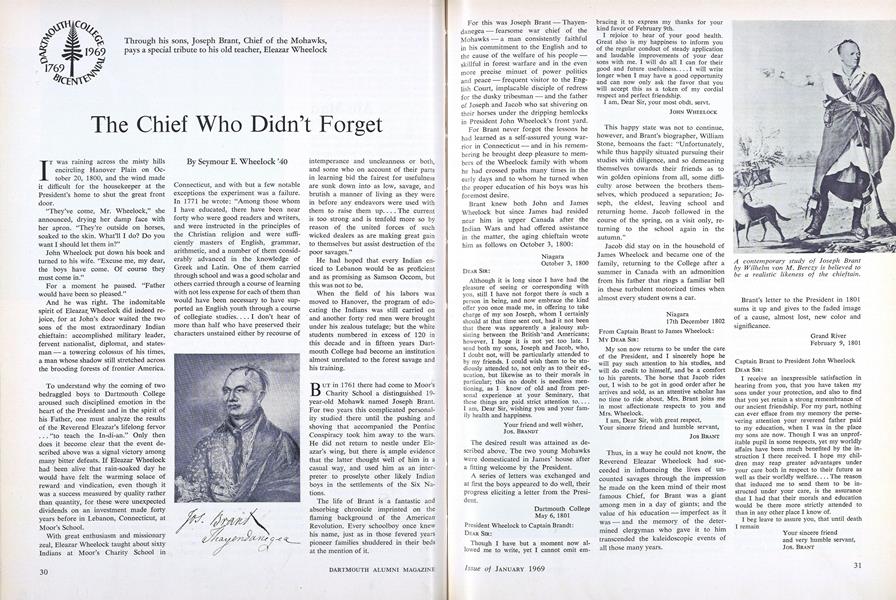

Through his sons, Joseph Brant, Chief of the Mohawks, pays a special tribute to his old teacher, Eleazar Wheelock

It was raining across the misty hills encircling Hanover Plain on October 20, 1800, and the wind made it difficult for the housekeeper at the President's home to shut the great front door.

"They've come, Mr. Wheelock," she announced, drying her damp face with her apron. "They're outside on horses, soaked to the skin. What'll I do? Do you want I should let them in?"

John Wheelock put down his book and turned to his wife. "Excuse me, my dear, the boys have come. Of course they must come in."

For a moment he paused. "Father would have been so pleased."

And he was right. The indomitable spirit of Eleazai; Wheelock did indeed rejoice, for at John's door waited the two sons of the most extraordinary Indian chieftain: accomplished military leader, fervent nationalist, diplomat, and statesman - a towering colossus of his times, a man whose shadow still stretched across the brooding forests of frontier America.

To understand why the coming of two bedraggled boys to Dartmouth College aroused such disciplined emotion in the heart of the President and in the spirit of his Father, one must analyze the results of the Reverend Eleazar's lifelong fervor . . . "to teach the In-di-an." Only then does it become clear that the event described above was a signal victory among many bitter defeats. If Eleazar Wheelock had been alive that rain-soaked day he would have felt the warming solace of reward and vindication, even though it was a success measured by quality rather than quantity, for these were unexpected dividends on an investment made forty years before in Lebanon, Connecticut, at Moor's School.

With great enthusiasm and missionary zeal, Eleazar Wheelock taught about sixty Indians at Moor's Charity School in Connecticut, and with but a few notable exceptions the experiment was a failure. In 1771 he wrote: "Among those whom I have educated, there have been near forty who were good readers and writers, and were instructed in the principles of the Christian religion and were sufficiently masters of English, grammar, arithmetic, and a number of them considerably advanced in the knowledge of Greek and Latin. One of them carried through school and was a good scholar and others carried through a course of learning with not less expense for each of them than would have been necessary to have sup- ported an English youth through a course of collegiate studies.... I don't hear of more than half who have preserved their characters unstained either by recourse of intemperance and uncleanness or both, and some who on account of their parts in learning bid the fairest for usefulness are sunk down into as low, savage, and brutish a manner of living as they were in before any endeavors were used with them to raise them up.. . . The current is too strong and is tenfold more so by reason of the united forces of such wicked dealers as are making great gain to themselves but assist destruction of the poor savages."

He had hoped that every Indian enticed to Lebanon would be as proficient and as promising as Samson Occom, but this was not to be.

When the field of his labors was moved to Hanover, the program of educating the Indians was still carried on and another forty red men were brought under his zealous tutelage; but the white students numbered in excess of 120 in this decade and in fifteen years Dartmouth College had become an institution almost unrelated to the forest savage and his training.

BUT in 1761 there had come to Moor's Charity School a distinguished 19-year-old Mohawk named Joseph Brant. For two years this complicated personality studied there until the pushing and shoving that accompanied the Pontiac Conspiracy took him away to the wars. He did not return to nestle under Eleazar's wing, but there is ample evidence that the latter thought well of him in a casual way, and used him as an interpreter to proselyte other likely Indian boys in the settlements of the Six Nations.

The life of Brant is a fantastic and absorbing chronicle imprinted on the flaming background of the American Revolution. Every schoolboy once knew his name, just as in those fevered years pioneer families shuddered in their beds at the mention of it.

For this was Joseph Brant - Thayendanegea - fearsome war chief of the Mohawks - a man consistently faithful in his commitment to the English and to the cause of the welfare of his people - skillful in forest warfare and in the even more precise minuet of power politics and peace - frequent visitor to the English Court, implacable disciple of redress for the dusky tribesman - and the father of Joseph and Jacob who sat shivering on their horses under the dripping hemlocks in President John Wheelock's front yard.

For Brant never forgot the lessons he had learned as a self-assured young warrior in Connecticut - and in his remembering he brought deep pleasure to members of the Wheelock family with whom he had crossed paths many times in the early days and to whom he turned when the proper education of his boys was his foremost desire.

Brant knew both John and James Wheelock but since James had resided near him in upper Canada after the Indian Wars and had offered assistance in the matter, the aging chieftain wrote him as follows on October 3, 1800:

Niagara October 3, 1800

DEAR SIR:

Although it is long since I have had the pleasure of seeing or corresponding with you, still I have not forgot there is such a person in being, and now embrace the kind offer you once made me, in offering to take charge of my son Joseph, whom I certainly should at that time sent out, had it not been that there was apparently a jealousy subsisting between the British and Americans; however, I hope it is not yet too late. I send both my sons, Joseph and Jacob, who, I doubt not, will be particularly attended to by my friends. I could wish them to be studiously attended to, not only as to their education, but likewise as to their morals in particular; this no doubt is needless mentioning, as I know of old and from personal experience at your Seminary, that these things are paid, strict attention to.... I am, Dear Sir, wishing you and your family health and happiness.

Your friend and well wisher, Jos. BRANDT

The desired result was attained as described above. The two young Mohawks were domesticated in James' house after a fitting welcome by the President.

A series of letters was exchanged and at first the boys appeared to do well, their progress eliciting a letter from the President.

Dartmouth College May 6, 1801

President Wheelock to Captain Brandt:

DEAR SIR:

Though I have but a moment now allowed me to write, yet I cannot omit embracing it to express my thanks for your kind favor of February 9th.

I rejoice to hear of your good health. Great also is my happiness to inform you of the regular conduct of steady application and laudable improvements of your dear sons with me. I will do all I can for their good and future usefulness.... I will write longer when I may have a good opportunity and can now only ask the favor that you will accept this as a token of my cordial respect and perfect friendship.

I am, Dear Sir, your most obdt. servt.

JOHN WHEELOCK

This happy state was not to continue, however, and Brant's biographer, William Stone, bemoans the fact: "Unfortunately, while thus happily situated pursuing their studies with diligence, and so demeaning themselves towards their friends as to win golden opinions from all, some difficulty arose between the brothers them- selves, which produced a separation; Joseph, the eldest, leaving school and returning home. Jacob followed in the course of the spring, on a visit only, returning to the school again in the autumn."

Jacob did stay on in the household of James Wheelock and became one of the family, returning to the College after a summer in Canada with an admonition from his father that rings a familiar bell in these turbulent motorized times when almost every student owns a car.

Niagara 17th December 1802

From Captain Brant to James Wheelock: MY DEAR SIR:

My son now returns to be under the care of the President, and I sincerely hope he will pay such attention to his studies, and will do credit to himself, and be a comfort to his parents. The horse that Jacob rides out, I wish to be got in good order after he arrives and sold, as an attentive scholar has no time to ride about. Mrs. Brant joins me in most affectionate respects to you and Mrs. Wheelock.

I am, Dear Sir, with great respect, Your sincere friend and humble servant,

Jos BRANT

Thus, in a way he could not know, the Reverend Eleazar Wheelock had succeeded in influencing the lives of uncounted savages through the impression he made on the keen mind of their most famous Chief, for Brant was a giant among men in a day of giants; and the value of his education - imperfect as it was - and the memory of the determined clergyman who gave it to him transcended the kaleidoscopic events of all those many years.

Brant's letter to the President in 1801 sums it up and gives to the faded image of a cause, almost lost, new color and significance.

Grand River February 9, 1801

Captain Brant to President John Wheelock DEAR SIR:

I receive an inexpressible satisfaction in hearing from you, that you have taken my sons under your protection, and also to find that you yet retain a strong remembrance of our ancient friendship. For my part, nothing can ever efface from my memory the persevering attention your reverend father paid to my education, when I was in the place my sons are now. Though I was an unprof- itable pupil in some respects, yet my worldly affairs have been much benefited by the instruction I there received. I hope my children may reap greater advantages under your care both in respect to their future as well as their worldly welfare.... The reason that induced me to send them to be instructed under your care, is the assurance that I had that their morals and education would be there more strictly attended to than in any other place I know of.

I beg leave to assure you, that until death I remain

Your sincere friend and very humble servant, Jos. BRANT

A contemporary study of Joseph Brantby Wilhelm von M. Berczy is believed tobe a realistic likeness of the chieftain.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Green Curve of the Future

January 1969 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38 -

Feature

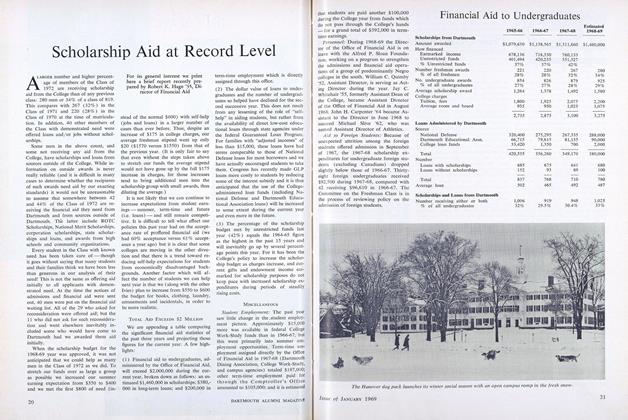

FeatureScholarship Aid at Record Level

January 1969 -

Feature

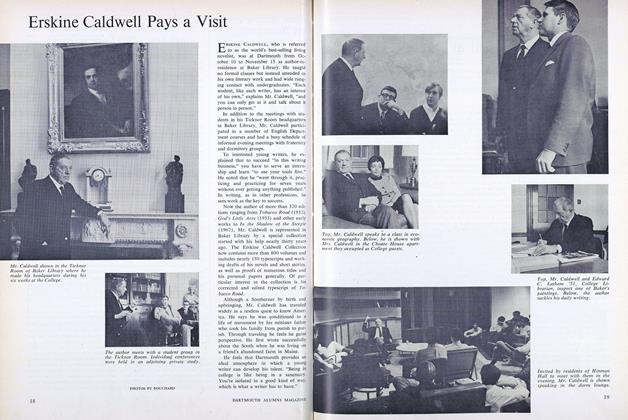

FeatureErskine Caldwell Pays a Visit

January 1969 -

Article

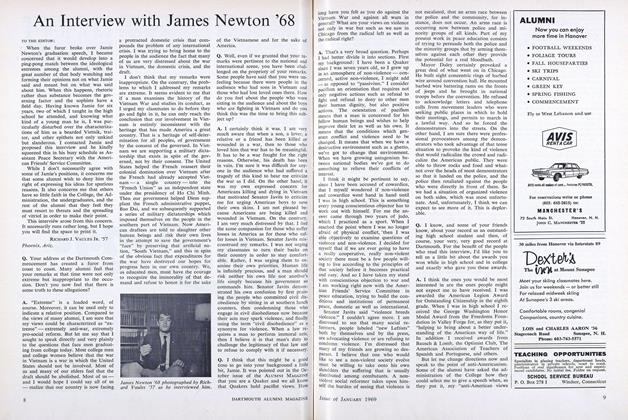

ArticleAn Interview with James Newton '68

January 1969 By RICHARD J. VAULES JR. '57 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1939

January 1969 By HENRY CONKLE, ALAN v. TISHMAN, ROBERT L. KAISER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1947

January 1969 By ROBERT B. KIRSCH, RICHARD HALLERITH

Seymour E. Wheelock '40

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWHAT OF ADMISSIONS AT DARTMOUTH?

October 1961 -

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1972 -

Cover Story

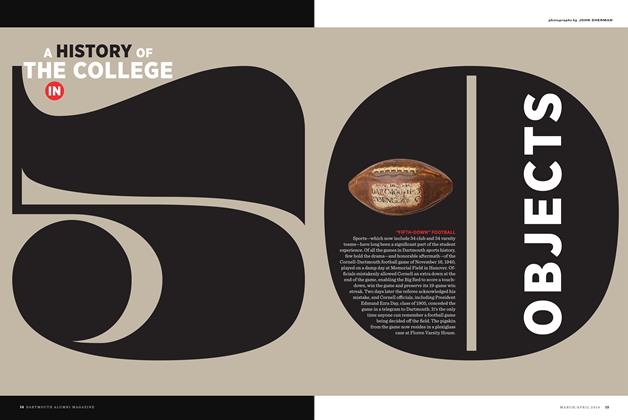

Cover Story"FIFTH-DOWN" FOOTBALL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureJazz Comes to College

November 1978 By Dick Holbrook -

FEATURE

FEATURERemnants of a Moment

MAY | JUNE 2016 By GAYNE KALUSTIAN ’17 -

Feature

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross