JAZZ was a music novelty in 1915. This son of ragtime and brother of the blues was impudent, restless, and comical. It had a universal quality that suited an era of aviation heroics and tin lizzie practicality. At about the same time that jazz was catching on in show biz it began to be heard at Dartmouth.

At the 1915 Winter Carnival concert, Bones Joy '16, Eddie Earle '17, and Slats Baxter '17 introduced this rousing new style of instrumental entertainment on banjo-guitar, piano, and traps. It was a live and lively echo of the raspy phonograph recordings of the Van Eps Trio, the avant garde combo at the Victor studios.

By 1916, the Campus Banjo Orchestra played the Carnival dance for the Phi Sigs, Tri Kaps, and Phi Gams with one-steps like "Mandy Lee" alternating with foxtrots like "Bill Bailey" and "Pretty Baby." Gyp Green '17 and John Sullivan '18 were stars of this six-piece group. They concocted a brand-new picking technique with pieces of celluloid for a snappier, jazzier sound than the old strumming.

Not long ago, Green and several other pathfinders of the Jazz Age in the North Country were asked to think back to the tempo of the times. Their memories of those days a half-century and more ago echo clearly, more durable than brittle discs salvaged from dusty attics. Green teamed with pianist Bill Cunningham '19 at Myer's upstairs eating club at 4 South Main and recalled that "Bill was bound to ruin any piano he pounded." Cunningham, the well-muscled center on "Iron Major" Frank Cavanaugh's football team, got himself hired as piano maestro when the Nugget movie house opened in 1916. He was the first of a string of gifted pianists who heightened the suspense, hilarity, or pathos of the silent films with ad lib jazzy accompaniments.

Jazz reinforcements arrived with the Class of 1920. Sal Andretta '20, who later held the U.S. Justice Department's highest career post, recently wrote that "Vince Breglio '20 and I took turns playing dances in the hall over the old post office with Jimmie Parkes '20 as the trap drummer." Parkes remembered: "I played for free lunch and supper at the Wheelock Club. Breg and I and violinist Al Lucier '18 were a threesome. Then came Paul Sample '20 (later Dartmouth's artist-in-residence) and his C-melody saxophone." When Lucier dropped out and Jim Reber '20 came in on banjo, Andretta switched to banjo, too, and they named themselves the Dartmouth '20 Five. Some of them toured with the Dartmouth Musical Clubs as an instrumental act called The Scrap Iron Four.

In the spring of 1917, the biggest jazz news on campus was the first phonograph record by the Original Dixieland "Jass" Band. Their "Livery Stable Blues" sold a million copies throughout America. The fad caught on. By 1918, the victrolas in fraternity houses, dorms, and homes were spinning "At the Jazz Band Ball," "Tiger Rag," "Bluin' the Blues," "Fidgety Feet," and similar classics of the new order by those Dixielanders (white musicians) from New Orleans. (It was at least another five years before the sensational black bands like those of the legendary King Oliver or pioneer Fletcher Henderson attracted much interest in the colleges. They simply weren't known. Those "race" records were segregated to music stores in Harlem, down on Chicago's South Side, or Negro districts in other cities.)

In late 1918, Governor Cox of Massachusetts invited the Dartmouth Jazz Band, now so titled, to play at the Smileage Ball at the Copley Plaza in Boston to help raise money for Liberty Bonds. Andretta reported: "We had a helluva time. Did a lot of good for Dartmouth and the war effort."

Before he died, Paul Sample wrote: "After the war, some of us returned to college, and we resumed playing at the Wheelock Club and for various dances in the area." His scrapbook has a snapshot of the reunited group: Paul, his brother Dinny Sample '2l, Breglio, Andretta, Reber, and newcomers Gordon "Gin" Plumb '22 and Ben Bishop '22. They played such 1919 favorites as "Hindustan," "After You've Gone," "Somebody Stole My Gal," and "A Good Man is Hard to Find." And surely they all listened to "Oh Frenchy" by Wilbur Sweatman's Jazz Orchestra, purchased at Bailey's in White River Junction, nearest source of canned jazz.

Jazz was soon to reach Dartmouth by a new medium. The Dartmouth Radio Club started meeting in Wilder Laboratory where, with sharp tuning and an earphone harness, a listener might hear Ted Lewis' first record, "Blues My Naughty Sweetie Gives to Me," crackling in from Station KDKA in Pittsburgh.

Anew and durable jazz-band name came into being for the Musical Clubs show in May of 1920. Bill Embree '21 explained it:

I decided to put together an act of acrobatic dancing and'jazz songs. I wanted a stage band that could play Dixieland music like the "Darktown Strutters' Ball." My band included Paul and Dinny Sample on saxophones, A 1 Curtis '22 playing trumpet, Homer Cleary '21 on piano, and Bill Terry '21 on the drums. I had a terrible time thinking of a name for the act, and during some wakeful hours at night I tried my best to think of something wicked, and hit upon "Barbary Coast" as being such - whether it was related to the buccaneers off the African coast or the section of San Francisco which used that name.

The review of the show in TheDartmouth said the palm for getting the most encores went to Underworld Embree and his Barbary Coast Five. After its first appearance, the band was built up to eight, with Plumb and Had Pinney '22 on sax and Charles Palmer '23 on trombone.

More about Cap Palmer. Tradition says that Dartmouth's canoeist and world traveler John Ledyard arrived by buggy from Hartford 'as a freshman in 1772 and that his baggage included materials for stage performances - including the costume of a Numidian prince. Well, Cap Palmer arrived in 1919 loaded for Jazz. His family drove him up from Boston. His baggage included a complete set of drums, a cowbell piano, a couple of trombones, a bass sax, a banjo, guitar, tin fife, and a megaphone for vocals. He made music during Delta Alpha, in Commons, and with the College band when he played jazz breaks on trombone in the performance between the halves at the football games.

Palmer was soon playing with the Barbary Coast. He recently recalled soft spring nights in 1920 after the Nugget let out. The piano in the Beta fraternity house was shoved out from the living room to the porch and a band session would just sort of happen. Piano, saxes, trumpet, banjo, and drums. Although a rank freshman, I was allowed in on trombone. It was all spontaneous. We played the current songs like "Ida, Sweet as Apple Cider," "Avalon," "Japanese Sandman," "La Veeda," "Dardanella," and "Shine." Nice slow tempos. We abhorred "Ja Da." Someone would call out a number. The piano would start it and the rest of us would join in, one by one, as we figured out the key. Word got around campus and guys would begin to drift in to listen. We played for hours. There might have been hundreds sitting all around the area. It was one of the many things that contributed to the Dartmouth spirit.

On June 8, 1920, an advertisement for Allen's drug store in Hanover first mentioned Victor victrolas and records. Hot dog! The Dartmouth students at last had ready access to a liberal education in jazz music. Jim Campion, always the enterprising merchant, soon competed with Brunswick records, and later added Columbia and Okeh in the special downstairs Smoke Shop. Paul Whiteman, the front-running favorite of the 1920s dance bands, cut his first records that summer: "Whispering" (very low-profile jazz) and "Wang Wang Blues" (which lent itself admirably to hot breaks and jazzy licks).

When the 1920 football season opened, music was a big part of the autumn ritual. At the bonfire rallies beforehand. On the train to out-of-town' games - usually woodshedding up in the baggage car. At the game, of course. And, for the jazz lovers, at the dances after the game. Palmer remembered they were called brawls. Usually at the Plaza in Boston, or the Biltmore or the Commodore in New York. Never in New Haven. "We played in tuxedos with soft shirts. Gordon's gin was our official beverage."

In 1920-21, the Barbary Coast regulars were augmented, from time to time, by Mai Johnson '21 on drums, a well-regarded trumpet player named Taylor in '21 or '22, Walt Sands and Dick Willis '22, Bob Hight '22 or Mox Hubert '23 on banjo, Hal Baker '23 (another of the Nugget piano virtuosi), George "Spike" Hamilton '23 (who made a career of band leading), and Red Holbrook '24. On very rare occasions Charlie Zimmerman '23 contributed his violin-playing, which, he cheerfully admitted, was "terrible," but "the rest of the band covered up for me!"

ZIMMERMAN'S contribution to Dartmouth's jazz was considerably more than his violin-playing. He wrote:

I had the idea for a different type of college dance. My high-school classmate Denis Maduro (at Cornell) and I organized the First Inter-Collegiate Ball. It would be held in the main ballroom of a well-known hotel. It would run from 9:30 to 3:00 a.m. rather than the usual nine to twelve. It would feature one or two Broadway song and dance stars such as Marilyn Miller. It would have continuous music with two or three bands competing for crowd approval. And the tickets would cost $5.50 rather than the customary $3.00.

Zimmerman and his friend engaged the Big Four, an eight-piece band from Cornell, and the Barbary Coast, then managed by Dick Willis. They borrowed a few hundred dollars and rented the ballroom of the Commodore Hotel in New York and decorated it with modern cartoons. They advertised in a number of eastern college newspapers. To say that it turned out to be a riotous success would be rank understatement. Before the evening was over, the New York fire and police departments were both on duty, and Zimmerman was at the door of the hotel regretfully refunding money to the hundreds who had to be refused lest the hotel collapse. For the next three years, every Thanksgiving, Christmas, and Easter another Inter-Collegiate Ball took place in either Boston or New York. Plus a couple in Paris during the summers. The Barbary Coast played at each of them - and quickly won much more than local fame. Also, the Barbary Coast was selected by the Cunard Line to furnish the music for its original student third-class European tour, and every summer a representation of the band played on the French Riviera.

In 1921-22, both Dick Willis and Spike Hamilton were important factors in the success of the Barbary Coast. Palmer said:

Dick was one hell of a promoter - and always laughing and calling out to the crowd. He dug up the jobs for us. We were a co-op band, but Willis, as the promoter, got one extra share of the take. Spike was our out-front leader of the big band. He was tall, craggy faced, with a mane of yellow hair. Had a great smile. A good, but square, violinist. One night, as Spike played, hair tossed back and eyes closed, the rest of the band, one by one, dropped down off the stand until nothing was left but an unattended bass drum. Spike's soaring, moaning violin was left alone in the beautiful blue spotlight. The chorus ended. Spike turned around, flung out his arms and said, "Hit it, fellows." The lights blazed up - to a very empty stage.

Wallie Lord '24, saxophone, was typical of many of the early-day student musicians. He wrote:

I played sax at Ma Brown's eating club and various other eating clubs all during my college career. I also played some dance jobs in surrounding towns. [He enclosed a 1921 ad: 100 GIRLS want dance partners to follow the Dartmouth Jazz to Lebanon tonight, Monday, November 7th. All set. Let's go. Spike Hamilton. Wallie Lord. Bob Hight. Bill Perry. Dick Willis, Director. At Etna on Wednesday night.] In 1922, I made the Musical Clubs tour south in the spring. And the following year, too. I played with the Barbary Coast in New York in a battle of music with Rudy Vallee's band from Yale. I also played piano at the Nugget - taking the 2:15 show - usually something like "Wang Wang Blues" during a torrid love scene.

In 1922-23, a new trumpet joined the Coast - a senior, well on his way to Phi Bete honors, J. Dudley Pope '23, who remembered:

In spring vacation, 1923, the Musical Clubs concert trip went as far west as St. Louis. After the concert, at the Chase Hotel, the manager offered our dance band the regular job there — ten men at $1,100 a week. We seriously considered it - for a few minutes. We stopped in New York City and cut a couple of records. I remember recording "Ida." We got the job of playing for the Junior Prom in 1923, instead of the usual nationally known orchestra. We added one pro, a piano player named Sid Reinherz, from Boston. As I look back on those days, they really were the most enjoyable of my life. I think I would have played in a dance band without being paid - it was that much fun.

Cap Palmer noted:

We picked up good stuff off the records as they came through. Our favorite spot was at Allen's, in the back marble-table-and-ice-cream-chairs section. They had a phonograph and shelves of records arranged numerically. All Victor. Four or five of us would gather around the machine and play, let's say, the new Original Memphis Five release - over and over and over - memorizing the essential melody lines as well as we could, including the breaks or figures of our professional counterpart. My idols were trombonist Miff Mole and his trumpet partner Phil Napoleon.

The band members were not the only ones who bought the new jazz records. Wind-up phonographs were to be heard in every dorm and fraternity house. By the summer of 1923, the best-sellers were Paul Whiteman and Ted Lewis. California Rambler records were just starting to come out on Columbia. Weems and Waring started recording for Victor. Isham Jones was established on Brunswick, and Abe Lyman helped popularize that label. This big-band music was often what the Barbary Coast boys called "magee" or "cook book," but some very sharp jazz could be heard by cats like Gus Mueller, Ray Lopez, Bill Moore, Adrian Rollini, Frankie Trumbauer, Louis Panico, and a few other sidemen who were "with it."

Student musicians appreciated without envy the polished jazz recorded by professional musicians. College bands made up the difference with their irrepressible joie de vivre. They had super self-confidence. One said: "We enjoyed a popularity entirely due to our enthusiasm and originality. We were all pretty good fakers and could improvise to most any tune that came along. Very few were proficient reading musicians." Another said: "All of us were highly talented. We needed no scores. The arrangements were joint ventures with everyone suggesting and participating. Breaks were worked out in a few minutes and no one ever forgot his part. Several of us had perfect timing, and all had fantastic musical memories." And that considered opinion hasn't changed in 50 years.

Roily Howes '28, banjo, said: "I know what made the band great. Dedicated jazz men of great talent who played together every day. We played for our meals and the good food made us strong and healthy: 45 to 90 minutes at lunch time every day - six, seven, or eight men - usually three saxes, piano, banjo, drums. Sometimes some brass. Sometimes a bass. This developed fantastic teamwork and the evolution of a style which led to fame." George Zahm commented: "Quite a few of us never paid a nickel for food all the time we were in college. All frugal fathers should see that their sons learn to play an instrument before going to Dartmouth."

ONE new commercial venture by the Barbary Coast was a record sponsored and sold by Campion's College Smoke Shop. It was recorded in the Columbia studios in New York in November 1924, and issued on the Personal Record series as 72-P, a two-sided, black ten-inch shellac disc with a creamcolored label. Titles: "San" and "Wabash Blues" - by the Barbary Coast Orchestra. It was a sell-out. Several members of the band still have their own copies. Personnel: George Zahm '25, Paul Dillingham '26, and Bob Slater '27, reeds; Paul "Sid" Hexter '25, piano and leader; Obie Barker '26, banjo; Walt Irvine '25, drums and trombone. Plus two added starters. Barker recalled; "The trumpet player was lent to us by the Columbia people. For two hours he tried to remodel us. His success was dismal." But in Zahm's opinion: "He put out some pretty fair licks that still sound pretty good today."

Woody Burgert '27, trumpet, said: "I didn't play on that recording, but I have it, and it's been played ten thousand times." Record collectors consider the Barbary Coast recordings choice examples of that era. A copy in excellent playing condition would go at auction for $20 or better. Burgert singled out three fellow musicians for special praise: "Cap Palmer for his highly personal and peerless playing of 'lda'; Paul Dillingham, the one true virtuoso of this or any band, pronounced 'the greatest' by men from the big bands who filled in with us at the notorious InterCollegiate Balls; and Bob Slater, a sound musician and charming companion."

Bob Slater had some lively recollections of the 1925-26 edition of the Barbary Coast:

We played prom dates at Smith, Holyoke, and Skidmore. Regardless of where we had been, we usually wound up on Sunday afternoon with a tea dance at the Plym Inn in Northampton. It was there that Cliff Randall, our in-house Sinatra, fell off the stage into the receptive arms of an anonymous Smithie while singing "I've Got a Feeling I'm Falling," thus demonstrating what good timing we had. Coming back from an early spring prom date at Skidmore in the wee hours of another Sunday morning, in Harry Eastman's 1921 Cadillac limousine taxi, snow began falling as we left Saratoga. By the time we neared the crest of Rutland Mountain, it was axle-deep, and we had to stop. Nine of us in the car. No light. No heat. At long last came the dawn! We chipped frost off the window to see out, and guess what - not a hundred yards away was a big logging camp. They fed us fried eggs, bacon and flapjacks, and hot apple pie. With a big assist from the crew, we got the car over the hump and headed back for Hanover.

In the college year of 1926-27, two outstanding musicians came to prominence: Ed Plumb '29 and Russ Goudey '29. Bob Slater described Ed's brilliant alto sax playing, his great originality, and keen imagination. Ed became a senior arranger for the Walt Disney productions. Russ Goudey led the Barbary Coast both his junior and senior years, was proficient on many instruments, composed, arranged, and directed. He was director and conductor of the Philco radio programs, served as music consultant to film studios and recording companies, finally forming his own company as a musical consultant in 1948, and is still fully involved in film assignments.

In the spring of 1927, the Barbary Coast Orchestra of Dartmouth recorded another two numbers on the Columbia Personal Record series, 94-P, for Campion's College Smoke Shop. The titles were "Weary Blues" and "Canzone-Amorosa." Both were fox trots and "arranged by M. R. Goudey." Personnel included: Randall, Slater, and Goudey on reeds; Chuck Peacock '3O on banjo; Red Kennedy '29 on tuba; Phil Thompson '27 on piano; and Lew Beers '28 on drums. One trumpet (and accordion) was Johnny Hahn '30. A second trumpet was Keith Preston of Hamilton College. The trombone player was Howard "Miff' Berg from the University of Pennsylvania. Both Preston and Berg were frequent and welcome participants with the Barbary Coast. And still are - both men attended the 1977 reunion in Hanover, and afterward Nat Morey reported that "Keith's and Howie's lips held out. We had three-part harmony throughout, and the band was really great." On the 1927 record date, both men took fine 16-bar solos. Russ Goudey played a beautiful alto sax solo on "Weary Blues."

NINETEEN TWENTY-SEVEN was the peak year for memorable recorded jazz. It was "that wonderful year" when Paul Whiteman featured the Rhythm Boys, both Dorseys and the fabulous Bix Beiderbecke on silky jazz treatments like "Changes." Red Nichols and his Five Pennies recorded one hot hit after another. Ted Lewis engaged Ruth Etting for a smooth "Keep Sweeping the Cobwebs Off the Moon." Ben Pollack had Benny Goodman and Glenn Miller. Coon-Sanders and their Night Hawks knocked us out with "Sluefoot." Charles Dornberger recorded the most sensational "Tiger Rag" on wax. The New Orleans Owls treated record aficionados to "That's A Plenty." The California Ramblers did a tuneful "Mine, All Mine." Duke Ellington created the style-setting "Black and Tan Fantasy." Louis Armstrong and his Hot Seven recorded what are today among the most sought-after examples of his genius. And Jelly-Roll Morton's Red Hot Peppers continued with his own unique series of hot classics.

So much for the first dozen years of jazz at Dartmouth. Those of us who could afford to buy one - maybe two - new records a week had joyful, listening at Allen's and Campion's. With the records and the likes of the Barbary Coast we had a bonanza.

Memories

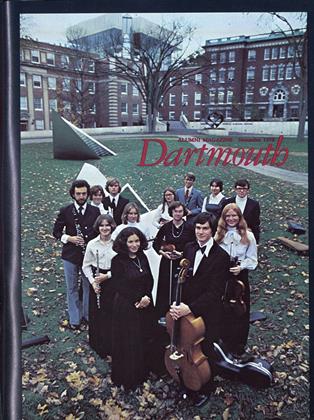

The Dartmouth '20 Five — plus three (from left): Jimmie Parkes, Sal Andretta,Paul Sample, Dinny Sample, Al Lucier, Vince Breglio, Jim Reber, and Don MacDonald.The photograph, from Paul Sample's scrapbook, was taken in late 1917.

At the Jockey Club Ball in Biarritz, summer of 1927 (from left): Cliff Randall'27; Keith Preston, Hamilton College '27; Russ Goudey '29; George Kennedy'29; Lew Beers '28; Howard Berg, Penn '30; Ken Semple '26; Phil Thompson '27.

Dick Holbrook '31 has been a recordcollector since 1926 and a researcher andwriter on jazz for 30 years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureMaking Music

November 1978 By Dana Grossman -

Article

ArticleThe Joy of Moving

November 1978 By W.B.C. -

Article

ArticleMan of the Cloth

November 1978 By M.B.R. -

Article

ArticleWhy the NCAA

November 1978 By SEAVER PETERS '54

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTo Screenwriting Born

November 1982 By Budd Schulberg '36 -

Feature

FeatureQuartet in Residence

October 1975 By DAVID WYKES -

Feature

Feature... AND MANY DARTMOUTH YESTERDAYS

October 1961 By Edward Connery Lathem '51 -

Feature

FeatureA BLUE-CHIP ASSET FOR 50 YEARS

APRIL 1964 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21, CLIFFORD L. JORDAN JR. '45 -

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

OCTOBER, 1908 By Horace Porter -

Feature

FeatureONE HUNDRED MASTER DRAWINGS

October 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40