Prof. Robert A. McKennan '25 calls his last class "a rite of passage" to the tribal rank of Emeritus

Professor McKennan, who retired in June,held his last class (Anthropology 62) on themorning of June 5. His farewell lecture,given in the presence of colleagues andfriends as well as students, took the formof a brief history of Dartmouth's Department of Anthropology, in which he has beenthe leading figure.

THIS marks a last time for both of us, and in a sense is an historic occasion. For me this is the last time I shall be able to lecture as Professor of Anthropology after this, it will be as Professor of Anthropology Emeritus. For you, it is the last time you will be able to attend the final class of someone who has taught 40 years at Dartmouth. I have checked with the Treasurer's Office, and there is only one person left on the faculty who, if he stays on, will be able to teach his last class in the 1990's, having then taught 40 years here.

Actually, I began teaching here more than 40 years ago; when I graduated in 1925, I returned in the fall to teach a freshman general education course called "Problems of Citizenship." I shudder to think what I may have said — or may not have said in that course! I taught the Class of 1929 when they were freshmen. Ed Kennard, who established the Department of Anthropology at Pittsburgh, was in one of my classes. (He was a Visiting Professor of Anthropology here a year ago.) The Chairman of the Department of Philosophy at Johns Hopkins was in my class, also the President of oberlin, and the Dean of the Law School at Stanford. (I mention these old students in particular because there seems to be a feeling around that Dartmouth wasn't an intellectual institution until recently.) In the Class of 1929 were also our present President and two members of the Board of Trustees, but I can't claim any responsibility for them, since I didn't teach them.

This in a way is a rite of passage. I will minimize the torture element as far as the initiate is concerned, and also the onlookers. As some of you know, it is customary in the tribe whose culture I know best for the old men to gather the young men together in the winter months and to pass on the oral and legendary history of the tribe. So let us move from Scottie Creek Titus' tent where we witnessed a shamanistic ceremony a day or so ago to Nabesna Bob's camp, and I will tell you something about the history of anthropology at Dartmouth.

I was not the first anthropologist to come to Dartmouth. The first one came in 1909, Charles Hawes. He had helped to excavate the Palace of Knossos in Crete. He had studied at Cambridge and had taught at the University of Wisconsin for two years before coming here. He started the program in anthropology at Wisconsin and he started it here. On the basis of Hawes' appointment, the University of Wisconsin has claimed membership in that select group of American institutions that were offering anthropology taught by an anthropologist in the first decade of the 20th Century. Since Hawes came to Dartmouth in 1909 there is no reason why Dartmouth too cannot lay claim to the same fame. Hawes came here in the Sociology Department with the title of Instructor in Archaeology. As was often the case in those days, members of the social sciences were asked to teach courses in Tuck School, and for one year Hawes taught a course in money and banking. I have talked with alumni who were in Tuck School at that time, and I gather that Hawes was more effective as a teacher of archaeology. When Hawes left here 1917 to go to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, he held the title of Assistant Professor of Anthropology, so I can't even claim to be the first person to hold a Dartmouth appointment in our discipline. However, I can claim to be the first man to hold the title of full Professor of Anthropology here at Dartmouth.

The next man to teach anthropology was Malcolm Willey, who came here in 1923. Although he was a sociologist, he had studied under Franz Boas, and he had been a close friend of Melville Herskovits at graduate school. Willey instituted a course in cultural anthropology in the spring of 1924, and I took it the first year it was given. Willey left to go into administrative work at Minnesota. He thought of it as a move to greener pastures. (Imagine a professor today thinking that administrative work constituted greener pastures!) This present course is the lineal descendant of the old Sociology 22, as set up by Willey in a straight Boasian tradition. I haven't gotten very far away from it.

Willey left in 1927, and was succeeded by Edwin Harvey, who came to us from Yale-in-China. He did his dissertation on Chinese religion and magic. (So you see there was an earlier Harvey here who had an interest in such subjects.) He added Sociology 21, which was the precursor of Anthropology 1. He had studied under Sumner at Yale, who wrote the 3-volume Science of Society, and Harvey ran the course in the Sumnerian tradition, which was quite like that of Morgan and Tylor.

I returned here in 1930 as Instructor in Sociology, having spent two years of graduate study in anthropology at Harvard and one year in the field studying a group of Northern Athapaskan Indians. Since Harvey was already teaching Sociology 21 and 22, I set up two courses on the American Indian (Sociology 25, The North American Indian, and Sociology 26, Central and South American Indians). Some of you have been exposed to (or are refugees from) my present course on The American Indian. In that first class in anthropology I had only four students. One was an Iroquois himself; one, Bill Fenton, became an international authority on the Iroquois and could now teach the Iroquois how to be Iroquois — his bibliography runs to some 100 items; one was a captain of the water polo team (we had a game then which was legalized underwater mayhem and later was eliminated by the Athletic Council before anybody was killed)—he was something of an anthropologist at heart, and went into the importing business. I used to get postcards from him mailed from all corners of the globe. The fourth man was just a good citizen. I have lost track of him — he is probably a bank president.

A number of professional men, scattered all over the country, came out of those early classes. I have already mentioned Fenton. I remember a Psychology major who became interested in the meaning of color and did his term paper for me on the different symbolic meanings that color had for different cultures. That man, Charlie Osgood, has been working on the problem of perception and meaning ever since, and is the Director of the Institute for Communications Research at the University of Illinois. Not long ago he served as president of the American Psychological Association. Another student who was interested in the Central and South American Indians became chairman of the Department of History at the University of Chicago, and has also served as president of the American Historical Society.

It was not until the postwar period, when Professor Harp came to the Museum as Curator of Anthropology, that we really got something going in anthropology. Sociology was going in one direction and anthropology in another. The few interested students we had in those days had to strain through many bushels of sociological chaff to get a few grains of anthropological wheat. That was the beginning of the new breed of anthropologists the breed of which you people are a part: Tom Stone, who founded the department at West Virginia; John Cook at the University of Alaska, now working with me on our research project; Cliff Lamberg-Karlovsky, who has specialized on the beginnings of agriculture in Persia and is now Assistant Professor of Anthropology at Harvard [recently appointed full professor and Curator of Near Eastern Archaeology in the Peabody Museum]; Dave Hally, who is building up a department at the University of Georgia; Dune Mathewson, who studied at the Universities of Edinburgh and London, and is in charge of the Upper Volta Archaeological Survey in Ghana; Paul Kaplan, who has done his field work in the Philippines and is taking his Ph.D. at Cornell.

Now we have our own major, our own building, and our own staff, and more than 20 Anthropology majors have gone on to graduate work in the subject. I am not trying to emphasize the professional aspects, but it does seem to me that with Professors Harp, Fernandez, Alverson, and Gregory, who is coming next fall, we are on our way to building up a Dartmouth School of Anthropology, and this is something we can be proud of.

I have given you, with malice aforethought, a microcosmic history of the youngest department at Dartmouth, because it seems to me this in a way reflects some of the things you might think about in regard to the history of the College.

One of these is a sense of historical continuity. The present is a product of the past, and the future can't help but be a product of both. No institution should be tradition-bound, and change is clearly not only inevitable but desirable; but changes in an institution, just like changes in a department, should be congruent with changes in the greater society of which it is a part. They should be made with some feeling of responsibility to the past, and some responsibility to the future, and to those I hope are going to come in the future. All of us members of the faculty and certainly undergraduates dergraduate are here for a relatively short time, in relation to the life span of the College, or even the life span of the Department. It seems to me that we are here more or less by historical accident. Faculty are appointed for a variety of reasons, and in this age of great professional mobility, inevitably many will move on. Students are here at the most for four years. I will not deny that students are the real heart of this institution. But I also can't escape the conviction that we do have some kind of responsibility to the 200 years of earlier Dartmouth graduates who have helped make the College what it is today. Many of them are still living, and many of them are making more of a sacrifice than you realize to make Dartmouth the place that it is.

But we have an equal responsibility to the Dartmouth students to come, and desirable as it is to change, these changes should be in terms not only of the present good, but the future good of undergraduates. I would like to think that, just as we have had 200 years of undergraduates up to now, we will have a long-continuing line of similar students, and we who are here now bear a very real responsibility to them. Just as I have ticked off the few isolated cases of students that I remember, there will be a long-continuing line of similar students passing through Anthropology and through Dartmouth in the years to come.

The fire in my camp is getting low; perhaps it is time to bring this rite of passage to an end. As in all rites of passage, the initiate emerges with a new name ... no longer Professor of Anthropology, but Professor of Anthropology Emeritus. Like old soldiers, old professors never die, they simply fade away, and this old professor is going to fade away to you know where ... the Upper Tanana. As some of you know, in company with a former student, John Cook, I have an ambitious research project under way at Healy Lake, dealing with the prehistory and the ecology of central Alaska, and I hope to continue work there for the next two years. I am sending Dave Gilmour up there next week to join the advance party, with instructions to dig innumerable pits down to bedrock using only a small trowel, keeping the soil profiles straight and clean, and also to see that the mosquitoes are well under control, so that when this old professor arrives later in the summer he will find the hard work all done.

Thank you all for coming to my last class!

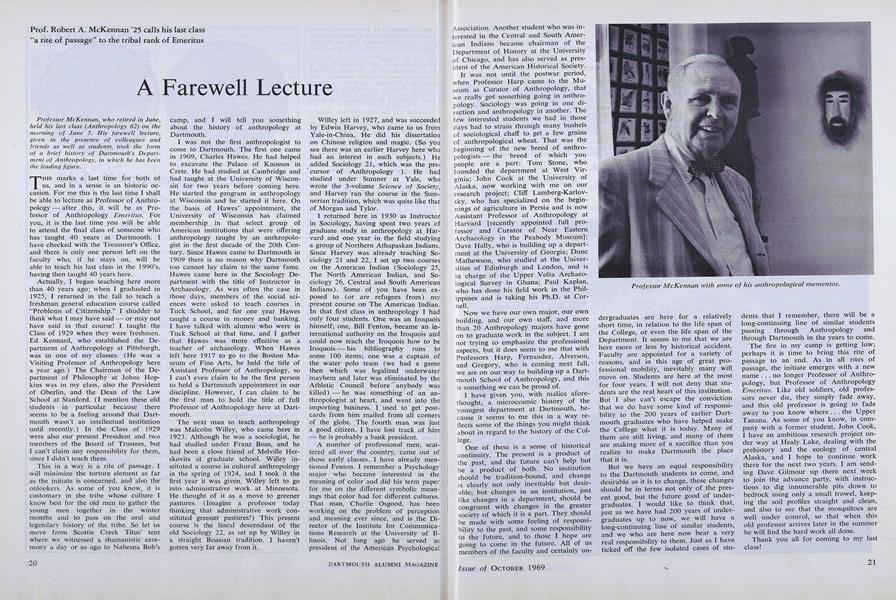

Professor McKennan with some of his anthropological mementos.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThird Century Fund Launches General Campaign Among Alumni

October 1969 -

Feature

FeatureThe Transcending Great Issues

October 1969 -

Feature

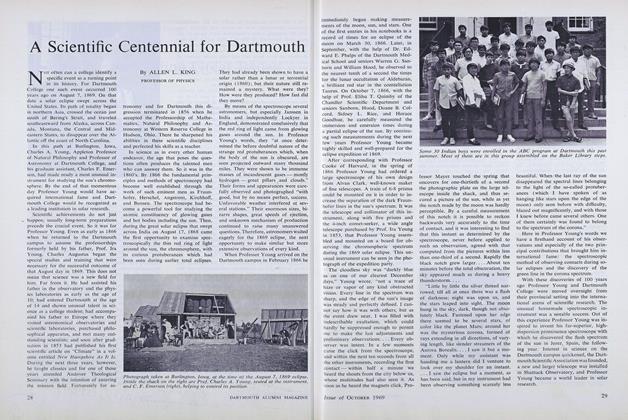

FeatureA Scientific Centennial for Dartmouth

October 1969 By ALLEN L. KING -

Feature

FeatureWhitewater Racing Gains New Status

October 1969 By JAY EVANS '49 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Draws Unusual Gifts

October 1969 -

Article

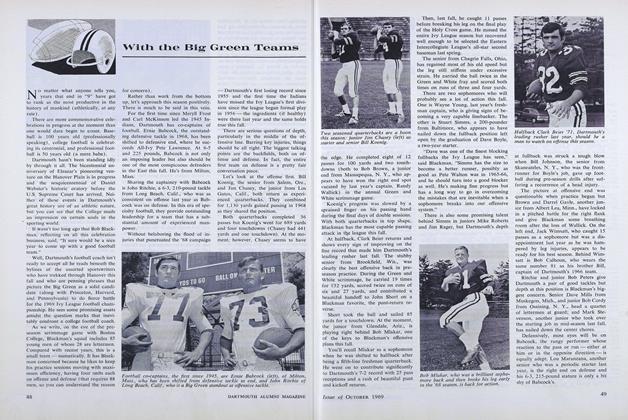

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

October 1969