ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

If you converse with these missionaries of Christiancivilization, you will be surprised ... to meet a politicianwhere you expected to find a priest.

—Alexis de Tocqueville, fromDemocracy in America

They are all Politicians, and they are all Scripture learnt.

British colonial officialtraveling in rural Connecticut

THE Reverend Eleazar Wheelock was a very pious man who would never have taught Indians in the wilderness of New Hampshire had he not also been very shrewd. He used careful planning, hard work, the influence of friends and relatives, opportunism, and outright deception to obtain a charter for the college he wanted to establish. The document itself - most of which Wheelock wrote - reflected his astuteness. It guaranteed his personal domination of the institution although legal authority was placed in the hands of others. It contained a somewhat inaccurate statement of purpose because Wheelock knew that absolute honesty would alienate the group of Englishmen who controlled the money he needed to implement his ambitions; the college, not accidentally, was named after the most influential member of that group, Lord Dartmouth. The man who granted him the charter - young and energetic Governor John Wentworth - wanted strong Anglican representation on the Board of Trustees, yet Wheelock managed to keep the number small. Indeed, the twelve-man board contained nine Congregationalists, including two of Wheelock's relatives and other personal friends from Connecticut. All in all, it was a superb political performance.

Wheelock felt he needed money, land, and a charter to launch what he often called "ye affair."* By 1768 he had the money. He had sent his star Indian pupil, Samson Occom, and a minister named Nathaniel Whitaker to raise funds in England for the education of American natives; they accumulated over £ 12,000 in contributions and subscriptions while spending only £.1000 He also knew he would have little difficulty finding a location for whatever institution he founded. An associate seeking a large grant in the Ohio River valley had included Wheelock in his plans. New Yorkers in the Albany area had promised him both land and buildings. Several towns in Connecticut - including Lebanon where he ran an Indian charity school - seemed interested, as did a group of proprietors from his native province organizing a settlement along the Susquehanna River. Leading citizens in western Massachusetts urged him to come there. Western New Hampshire offered even more possibilities: not only did Wheelock have many friends in the area, but the colony's new governor had given twenty-one pounds to Occom and promised to grant a township for the charity school should it be relocated in his governance. The southern colonies presented still other as yet unexplored opportunities.

A charter, however, was not easy to come by. Wheelock already had a good deal of experience in the matter. For years he had been trying without success to obtain such a document for the school, mainly to attract additional financial support. He first petitioned the government in England through two men who sympathized with his effort to Christianize Indians. Lord Halifax, who received the memorial in 1761, thought a charter would be too expensive and advised Wheelock to have the Connecticut Assembly pass an incorporation law which imperial authorities would then ratify. But the Assembly, for quite understandable reasons, turned him down. Connecticut was a corporation created by a charter granted in the seventeenth century and, as such, enjoyed much more political independence than most other American colonies. Since English law prohibited one corporation from creating another, provincial leaders hesitated to take any action which might jeopardize their status. "Ye forming a Corporation within a Corporation might be of dangerous consequent to ye Peace and unity of the government," they explained, adding that "ye neighbor governments envy us our Charter Privileges and we fear that hereby we shall give them opportunity and occasion to disserve us." Wheelock notified his contacts in the mother country about the Assembly decision, hopeful that renewed efforts for a royal charter might be made. Again he was disappointed. Word came back from England's leading evangelical preacher, George Whitefield, that without Assembly approval no charter could be obtained; Whitefield's influential patron, the Earl of Dartmouth, agreed. For the next few years Wheelock kept pestering his friends in the Connecticut government, but gained nothing except a reputation for perseverance.

When he began to think seriously about moving the Indian school and perhaps starting a college for missionaries - the idea is first mentioned in a letter written during the summer of 1763 - Wheelock renewed his efforts to obtain a charter in England. General Phineas Lyman, the man seeking a land grant in the Ohio River valley, was asked to use his influence with the Ministry. Wheelock also sought advice on how to proceed from churchmen and public officials in the colonies, and may have instructed Whitaker to work on the project. The results were far from encouraging. One correspondent in Pennsylvania who knew much more about the inner workings of imperial government than Wheelock wrote that it was "not so easy a Matter as many may be ready to imagine even to get Access to the Court; much more difficult is it to succeed in any Application for a favour." Recent ferment in the colonies over the Stamp Act, he noted, made success even less likely, for British officials would now be reluctant "to favour any Design recommended from America, especially if carried on by Dissenters." Whitaker reported: "At present there is no hope of a charter, and if you should get one they will encumber it & make it worse than nothing." William Smith, a leading New York barrister who served as Wheelock's main source of legal information, told him to keep trying, but recommended a plan of attack obviously doomed to failure.

MEANWHILE incorporation had taken on new importance. Whitaker had transferred the power of attorney given him by Wheelock to an independent Trust which included Lord Dartmouth as president, a well-known philanthropist named John Thornton as treasurer, and Robert Keen as secretary; the Trust, Whitaker's English advisers argued, was necessary to assure potential patrons their donations would be well managed. Wheelock did not like the arrangement. To begin with, he wanted to control the money himself and the Trust might ask him to justify each and every expenditure. In addition, most Trust members were Anglicans who, although sympathetic with his general desire to educate Indians, might try to link his activities to the Church of England. His worst fears were confirmed when Keen wrote asking for a deed which empowered the Trust to choose Wheelock's successor when he died, and to refuse payment of bills drawn on the Trust's account. Since these terms were unacceptable - among other things Keen had suggested a missionary named Samuel Kirkland as the successor while Wheelock wanted his own son Ralph - he calculated his response carefully. First he sent Keen a superfluous power of attorney, ignoring the request for a deed completely. He waited two months, then wrote again, explaining why he could not accept Keen's term. The delay gave him time to make plans which, if successful, would keep the power of the English group to a minimum. By late November, 1767, he had decided to seek a charter in America, one which left control of the school in the hands of a local board of trustees: the English Trust would only distribute funds. "I don't see how ye Affair can be accommodated," Wheelock wrote Whitaker, "without Incorporation or at least a Trust here."

William Smith who in the 1740's had helped found the College of New Jersey (later Princeton), had drafted its first charter, and still served on its board of trustees — probably played a key role in shaping the strategy. When Wheelock asked in 1765 for advice on how to handle the funds to be collected in England, Smith offered three "hints." Whatever type of institution Wheelock founded, it should be run by "a set of Gentlemen in [Smith's emphasis] ye Colonies . . . who shall have all the power of the Corporation, as to the management of its Estates, supplying Vacanies etc.,. . ." There should also be "another set of sundry special friends in England, Scotland, Ireland and every Colony on the Continent, who are to be Correspondents with ye first Set, and only have ye general power of receiving Donations to be transmitted to ye first Set." Above all, the institution should be incorporated. "Incorporation," Smith wrote, "sets up ye scheme as an Object of Notoriety. Donors knowing ye name of ye body corporate give with legal certainty by last will or otherwise, & with great Ease and confidence than by searching out private friends who after all may not thought to be fit to be trusted - besides, if any are disposed to give Lands, or the income of Lands, or other real Estate, it faces ye trouble & expense of devising special deeds oftrust." Smith reiterated his thoughts several times, once commenting "that a Charter is more necessary for such an Institution in this Country than it can be in England. An incorporated Body," he explained, "will not only acquire Rights maintainable by Law in the Courts of Justice, but command the Favour of the officers of the Government, who, without this sanction, may at such distances from the Crown, oppress the undertaking in a thousand ways, and utterly destroy it."

Smith also made a few choice observations on Keen's proposal. The letter, he reported, "alarms me." It made clear the intention of "our English Friends" to throw "the Fund and School into the Hands of a pious bunch, to whom we are heterodox"; the Trust members, he stated simply, "have no confidence in us on this side of the water" because we are dissenters. Smith then offered a fresh piece of advice. After admitting his correspondent had "indeed a difficult Part to act," he suggested that Wheelock give the appearance of joining with the Trust until its money had been spent, but in the process "make no surrender . . . nor consent to any submissions." Success in this undertaking depended on his'capacity to alarm "their pious Fears that all will drop on account of your Jealousies and Disgusts, and themselves be brought into a scandal for subverting a Noble Design from party views." What part such fear played in the Trust's subsequent behavior is impossible to determine, but it is clear Wheelock agreed with much of Smith's thinking.

The way in which he complied with the request for a deed reflected this. In the spring of 1768 he sent a document establishing an American Trust, the members of which would be named in his will. The specific terms of the deed gave his successor also to be named in the will although Wheelock admitted he had chosen his son - and the American Board virtual control of the charity school. Even the efforts to comply with Keen's suggestions were ill-disguised attempts to minimize the power of the English Trust. If its members disagreed with Wheelock's choice of a successor they as well as the American Board could nominate candidates, but the selection of the American Board would be in charge until both boards agreed. The English Trust could protest drafts on its funds, but only if it gave notice in advance. Wheelock made elaborate excuses for not sending the deed earlier, and concluded his explanation with a masterpiece of circumlocution. "If this deed suits you," he wrote, "I shall be glad; or if you will please send me a draught of one yt will suit you better, I assure you I am ready to sign anything f will please God & subserve ye great design in view." Wheelock also mentioned his difficulties in deciding where to move his school; he said nothing about a colonial charter.

BUT a charter was very much on his mind. Indeed, by now Wheelock had all but eliminated from consideration potential locations in colonies where it seemed unlikely he could get an incorporation. Connecticut was out for this and a number of other reasons. Massachusetts had to be dropped also. Wheelock wanted to leave open the possibility of founding a college and the Bay Colony - like his native province - already had an institution of higher learning. Although the Governor apparently had no objection to giving Harvard some competition, the members of the Assembly did. Besides, Massachusetts was also a charter colony; Wheelock had no intention of getting entangled in the legalities of corporations creating other corporations. The last information he had about General Lyman in England offered no encouragement. The whole project seemed bottled up in Court; Lyman's only hope of success lay in the unlikely possibility that associates recently thrown out of office would somehow be returned. Despite Smith's advice to accept the Albany offer, Wheelock had long since given up on New York. One factor influencing his decision was Smith's insistence on a royal charter, which the wily minister interpreted as an indication provincial incorporation for an Albany school could not be obtained. Smith eventually admitted as much.

That left the Susquehanna region and New Hampshire. Wheelock may well have preferred the first until he learned that whatever the proprietors did - a few months later they voted a tract six by ten miles for the charity school - title to the land would be in doubt. Connecticut, New York, and Pennsylvania all claimed ownership, and the controversy would have to be settled in court. It would have been senseless to leave open the possibility of a judicial decision destroying his entire plan.

New Hampshire, on the other hand, looked quite promising. Wheelock didn't know whether he could get a charter there or precisely how to go about seeking one, but he did know political conditions in the province favored the success of his undertaking. New Hampshire was a royal colony governed in accordance with instructions written in England, and imperial authorities in other royal colonies had been willing to incorporate educational institutions. Furthermore, Wheelock had written the new Governor, John Wentworth, about moving the charity school to the upper Connecticut River valley and had received a most enthusiastic response. Wentworth reiterated his willingness to grant the school a township as long as Wheelock promised to remain in New Hampshire, and to make him a trustee.

Other circumstances made the idea of moving north attractive. In the first place, New Hampshire citizens had provided much of the financing for his charity school. Wheelock himself went to Portsmouth in 1762 to raise funds and through the influence of House Speaker Henry Sherburne (a friend of George Whitefield) obtained an Assembly grant of £150; when that ran out, Sherburne collected an additional sum through private solicitation. A second trip in 1765 was just as successful. John Phillips, a wealthy Exeter merchant who later became a college benefactor, donated £.100; many others contributed smaller amounts. That same year eight provincial officials wrote letters of recommendation for Occom and Whitaker before they left for England. When Wheelock found himself without money in 1767 he made a third trip to collect the £60 another Portsmouth resident had willed the school.

Secondly, in western New Hampshire Wheelock would be among men he knew and trusted. Many citizens from Lebanon and nearby communities had migrated to the upper Connecticut River valley after the close of the French and Indian war a few years earlier. These settlers not only shared Wheelock's religious convictions, but lived in a manner symbolized by Connecticut's reputation as the "land of steady habits." Steady habits mattered to Wheelock. Many Indian trainees in the past had fallen victim to the passion for hard drinking which marked all of colonial society, and he didn't want the problem to arise again. The only way to prevent trouble was to make sure sober and understanding Englishmen settled the region surrounding his school.

The upper valley also provided good access to Indians. By 1768 Wheelock had begun to experience difficulties in recruiting students for his charity school. Connecticut contained few natives of any kind. Other educators attracted the few Indians in Pennsylvania and New Jersey interested in Christian training. The charity school's main source of supply had always been the Iroquois nations in western New York, and now that seemed to be drying up in the heat of denominational and personal conflicts. Sir William Johnson, the Indian Commissioner whose sympathy for and understanding of tribal needs had given him immense influence among his charges, supported the Church of England. He had always been suspicious of New Englanders, especially those like Wheelock with evangelical tendencies; dissenting ministers who tried to bring up Indians, he felt, usually turned them into "a gloomy race." Naturally, then, when the church-sponsored Society for the Propagation of the Gospel decided to institute a crash program for sending missionaries to the frontier, Johnson began cutting his ties with the charity school. Wheelock, just as naturally, began looking elsewhere. He knew the northern part of what is now New Hampshire and Vermont contained some natives; equally important, the Caghnawaga, St. Francis and other Canadian tribes lived nearby. None of these groups had as yet come under Johnson's influence.

Finally, Eleazar Wheelock thought he might be able to found a college in New Hampshire. The province contained no incorporated schools. In the late 1750s a convocation of Congregational ministers had petitioned Governor Benning Wentworth (John Wentworth's uncle, who held office from 1741 to 1767) for a college, but the aging and cautious magistrate told them to wait until the war ended. When it did, a second petition, which many Connecticut ministers also signed, was readied; this time Wentworth proved more receptive, although he finally decided to veto the project unless the institution were placed under the Bishop of London's authority. The ap- pointment of a new governor stimulated a fresh burst of activity in which both clergy and laymen participated. Wheelock's last visit to Portsmouth coincided with that burst of activity. Doubtless he began thinking about coordinating his plans with those of his New Hampshire friends. They were primarily interested in training men for the dozens of unfilled ministerial posts in the province and Wheelock wanted to train missionaries, but the two goals seemed compatible. In fact, the fortuitous confluence of circumstance made founding a college a real possibility. Before it had been little more than a dream.

This, then, was the situation in June 1768. Wheelock had decided to use the funds collected in England to relocate his charity school and to broaden the scope of his educational activities. He felt he needed a formal corporate charter, in part to facilitate future financing, in part to prevent undue interference by the English Trust in what he considered his personal affairs. New Hampshire, in addition to its other advantages, appeared to offer the best opportunity for incorporation as a school; even a college charter - which would fulfill Wheelock's most ambitious expectations - was not out of the question. The affair, however, required careful handling. Wheelock had to know precisely what kind of support he could expect in New Hampshire. He had no idea how much to ask of John Wentworth. Would the new governor be receptive to the idea of a charter and, if so, would he be willing to make it a college charter? Perhaps Wheelock should aim lower and ask only for an academy, which had no degree-granting privileges. How should he deal with the members of the English Trust? Without doubt they would object to independent incorporation in America, just as they would find the deed he had recently sent unsatisfactory. And how much should he let Wentworth know about his relationship to the Trust? How much the Trust about his negotiations with Wentworth? Yes, the affair would require careful handling.

THE task of investigating New Hampshire Wheelock assigned to the Reverend Ebenezer Cleaveland, a former pupil and fellow Yale graduate who ministered to a congregation in Gloucester, Massachusetts. Cleaveland had been of help before; in 1762 he spoke in behalf of Wheelock's educational efforts to a number of New Hampshire communities. Wheelock instructed Cleaveland thoroughly. He should see the Governor, Council and House of Representatives, interview as many inhabitants as possible to see what they might be willing to donate to the school, travel to the upper Connecticut River valley to find a desirable location and, in general, stimulate interest in Wheelock's activities. The instructions mentioned nothing about a college or a charter. Cleaveland, in addition, should visit western Massachusetts and New York, although the manner in which Wheelock made the request suggested he had little serious interest in those areas. He didn't, but he did have something else in mind. He had decided to try to mollify the English Trust by letting them choose the new school site. Their choice would be based on a report of Cleaveland's trip which, given the nature of his instructions, undoubtedly would favor New Hampshire. It was a nice plan, and it worked beautifully.

Cleaveland could not have received a more enthusiastic reception. Soon after his arrival in Portsmouth he wrote Wheelock that he was "so crowded with company on the affair" he had no "leisure to write" and found time only by working "before people arise from their beds." The list of men offering land to the school read like a social register: Council President Theodore Atkinson — 500 acres; Provincial Secretary Theodore Atkinson Jr. - one right (usually several hundred acres) in some town; Councillors Peter Livius and Daniel Warner - one right each; two members of the Wentworth family and merchant John Moffat - one right each; Attorney William Parker pledged half a right and Attorney General Samuel Livermore 200 acres. In his report Cleaveland noted that the "gentlemen of the lower towns ... appeared universally desirous that the School should come into that Province, and were generous in their offers to encourage the same. The Governor, to whom Wheelock had written a note explaining Cleaveland's purpose, not only greeted him warmly but asked a provincial Deputy Surveyor to accompany him - free of charge - in his search for a good school location. Wentworth also dropped Wheelock a return note expressing his approval of the Gloucester minister's mission.

The trip west reinforced Cleaveland's growing conviction that New Hampshire would suit Wheelock's purposes. Any one of a dozen towns seemed well situated; inhabitants ants in all these and others promised to give land and commodities should the school be settled nearby. Wheelock lock may have stimulated some of the enthusiasm through the letters he sent to friends in the upper valley advertising ing Cleaveland's trip, but for the most part the eagerness of westerners stemmed from their conviction a school would be useful. Cleaveland explained their reasoning in his final report. "In this new country," he wrote, "there are more than 200 towns chartered, settled, and about to settle, and generally of a religious people, which do and soon will want ministers; and they have no college or public Seminary of Learning for that purpose in that Province - which want they apprehend may be supplied by this School, without any disadvantage to or interfering in the least with the general design of it." He also noted that "every one appeared desirous to have it in his own town," a fact not unconnected with general expectations the presence of "the Doctor" would enhance land values in the region.

Soon after Cleaveland arrived in Lebanon to give a first-hand account of the journey Wheelock made his next move. He informed Wentworth the Trust in England would make the final decision about location, but implied strongly that the choice would have to be New Hampshire. "As soon as the place for the school shall be fixed in your Province," he added, "I will appoint His Excellency the Governor for the time being a trustee on this side the water ..." Wheelock, probably after long thought, ended the sentence with the words: "till a legal incorporation may be obtained." It was the first time he had mentioned the idea of a charter to John Wentworth.

At this juncture Wheelock's campaign was interrupted by a series of events which stemmed in part from his penchant for clandestine maneuvering. One of his representatives at an important Indian conference in western New York committed a number of indiscretions, including public disclosure of secret instructions to obtain from the Iroquois a grant of land for the charity school. What Wheelock hoped to gain from the instructions is not entirely clear Sir William Johnson would have invalidated any such gift but there can be no doubt he soon regretted his action. When a messenger arrived to report what had happened, Wheelock, in his own words, became "filled with confusion." The episode threatened his entire project. The infuriated Johnson might submit a full report of the duplicity to England, perhaps even to the Trust. Worse still, as Indian Commissioner of all the northern colonies he might warn his fellow imperial magistrates (including Wentworth) against further cooperation with Wheelock. Wheelock did what he could to calm Johnson. Cleaveland, who had not yet written his report for the Trust, left immediately for the conference site prepared to offer both apologies and explanations. Letters asking for help went out to friends whom Wheelock thought Johnson respected. These gestures, however, accomplished little. Johnson complained about the meddlesome minister to several officials in England; he also removed most of the Iroquois from the charity school.

Wheelock may have been confused and embarrassed by all this, but he was not paralyzed. In fact, he pursued "ye affair" more intensely than before, knowing delay would only enhance the possibility of Johnson's obstructing his plans. He urged Cleaveland to prepare his report as quickly as possible, and began to collect supporting documents. When Cleaveland finished, Wheelock deleted all passages he considered inappropriate; one of them referred to the fact many in New Hampshire thought his school might eventually serve as a "Public Seminary or College" for the education of provincial ministers, not Indians. The arrival of a supposedly unsolicited letter from Portsmouth's leading Congregational minister, Samuel Langdon (later president of Harvard), spelling out the advantages of moving to New Hampshire gave Wheelock the final piece of evidence he sought. On December 23, 1768 he packaged his material and sent it to the English Trust. The accompanying letter read in part: "I have avoided giving my judgment which of the places ought to have the preference, as I could not do it without grieving some who are very dear to me, and offending others." It also included a lengthly description of how the "insuperable objections" which he once thought prevented him from giving serious consideration to the upper valley had been overcome, and a simple statement that "if the gentleman of the trust shall fix upon that as a place for it, I shall be well satisfied." Nowhere in the packet did the idea of incorporation appear.

Next, after a last flirtation with both the Susquehanna people and General Lyman, Wheelock turned his full attention to just that: obtaining a charter. Several circumstances made him uneasy about the matter. In the first place, Wentworth had not responded to the October trial balloon. Moreover, Wheelock's legal advisers doubted whether the Governor could grant a charter; the only way to avoid uncertainty, they said, was to get the King's formal approval. Then there was the problem of approaching Wentworth. Wheelock simply did not know enough about the man to calculate his behavior. Would he be offended if the question of legality was raised, and, if not, would raising the question make the young magistrate think he should ask permission from his superiors? Which would be worse - informing the Governor of the English trustees' opposition to a colonial charter or having him discover he had been kept in the dark about their attitude? Wheelock perferred to be honest. Deceiving Dartmouth, Thornton, Keen and their associates was necessary to the success of his undertaking, but the pluses and minuses of treating Wentworth in a similar manner seemed about even.

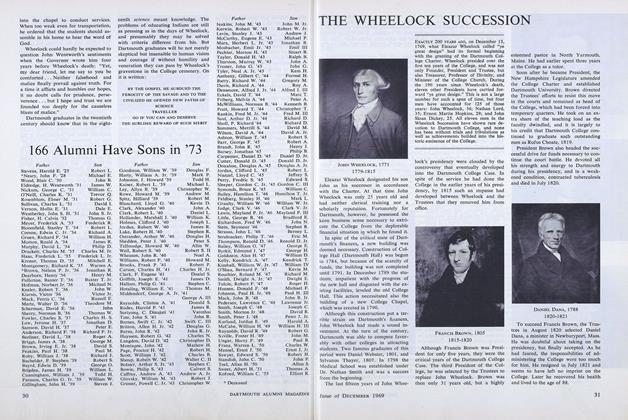

Wheelock almost played it straight. On March 13, 1769, he drafted a letter to Wentworth which explained why he could not think of moving to New Hampshire without a charter. "I understand," he continued, "it is disputable whether your Excellency has Power to grant such an Incorporation, however your Excellency knows whether your Grant of it, being ratified at Home, will not make it as Authentic as if it were granted by the King himself, and if it be necessary to send home for the establishment of it, and no preparation be made therefor, before the Place be fixed upon and I have received their Determination thereon." The confused syntax underlined the sensitivity of the questions asked, but it was clear Wheelock wanted to avoid the complications of having the charter dependent in any way on English approval. "There is another Difficulty in the affair of which it may be proper to advise your Excellency," the next paragraph read, "viz, that my Stand & Worthy Patrons the Gentlemen of the Trust... have steadily opposed any Incorporation at all, apprehending it will likely ... thereby become a Jobb. ... And your Excellency is able to determine whether an Incorporation may not be made for the School, leaving the Fund already collected in their hands ... and whether there will be any inconsistency or danger of Offense in so doing so long as the same Hand may still be trusted with it." The draft ended with suggestions about the contents of the charter and an offer by Wheelock to write the document himself.

Then he changed his mind. He wrote "not sent" on the letter, put it aside, and embarked on what seemed a less risky course of action.

The new plan involved two basic changes. He would use friends in Portsmouth as intermediaries in sounding out the Governor on the question of legality; the English trustees' opposition to incorporation would be kept a complete secret. That same day, March 13, Wheelock wrote Samuel Langdon. He made it quite clear only "want of an Incorporation" prevented his complying with Langdon's expressed desire to have the charity school moved to New Hampshire. "I wish you would get his Excellency's mind in this matter," Wheelock went on, without mentioning details, "and let me know by a line what he proposes to do in case it should be fixed there, and whether it would not be prudent in order to prevent loss of time to have a Draught prepared immediately." A second letter, this one to Portsmouth's other leading Congregational minister, Samuel Haven, was also sent. Within a month Wheelock had good news. Not only would Wentworth grant a charter, but he saw no necessity of having it ratified in England.

Several factors account for the Governor's response. Most important, he wanted Wheelock to move to New Hampshire as badly as the Connecticut cleric wanted to go there. Like many of his fellow colonists, Wentworth felt some moral responsibility for Christianizing pagans. He also thought that in a general way Indian education helped maintain royal authority in America; the charity school, he once wrote, would "produce the political advancement of His Majesty's Colonies by reclaiming a numerous people from their savage, desultory enmity to an orderly, peaceable, and happy subjection to the laws and advantages of his mild and equitable government." Conditions in his own province reinforced these sentiments. One of Wentworth's specific duties was to promote the expansion of settlement, and the Connecticut River valley contained huge tracts of unoccupied land; the Governor reasoned Wheelock's presence not only would reduce the likelihood of racial conflict, but would also alleviate the anxiety of potential migrants who feared such conflict. Furthermore, cooperation with Wheelock promised to reduce tensions in eastern parts of New Hampshire. The administration of his uncle had been disrupted by a series of political conflicts pitting an Anglican Governor and predominantly Anglican Council against a House of Representatives filled with dissenters. Benning Wentworth's refusal to grant the request of Congregational ministers for a college charter had made matters worse. John Wentworth, an Anglican himself, wanted to avoid repetition of what he considered his predecessor's mistakes. Cooperating with Langdon, Haven and other clergymen who supported Wheelock's proposals would provide visible evidence of his intention not to let denominational differences stand in the way of provincial progress.

The idea of incorporation probably didn't bother him in the least. He could understand Wheelock's reasoning: the school should be put in a position to hold property legally. Wentworth also understood enough about imperial politics - he spent nearly two years in England angling for various offices before the governorship became available - to know efforts either to seek a charter from the King or obtain formal ratification for anything he did would probably fail. But he was quite willing to act independently. Governors in other royal provinces had granted school charters without serious repercussions. His own instructions included the power to erect towns, boroughs, and cities - all incorporated entities. Besides, with men like the Earl of Dartmouth sponsoring Wheelock's enterprise, Wentworth's willingness to grant a charter might provide some political mileage. Dartmouth had in the past been president of the powerful Board of Trade and Plantations, and seemed destined for still higher office. New Hampshire's governor, of course, had not been informed of the Trust's opposition to incorporation; apparently the thought never entered his mind.

Wentworth may have had one additional reason for acquiescing in Wheelock's insistence on a charter. Like any other colonial governor, he knew his tenure in office depended in part on his cooperation — or at least the appearance of cooperation - with the Church of England. Wentworth worked on the problem in a number of ways: by professing the Anglican faith, by seeking membership in the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, by cornering friends about to embark for England and informing them of his efforts to promote the Church in New Hampshire, and by engaging in periodic correspondence with the Bishop of London, titular head of the Church in North America. Wheelock's school - assuming the Board of Trustees included a number of Anglicans - would give additional proof of his cooperativeness. The only way to influence the choice of trustees was through granting a charter, but only on the condition Wheelock appoint several churchmen; indeed, Wentworth made this perfectly clear when Langdon asked him about incorporation. The Governor later told the Bishop of London the founding of Dartmouth College was one of several "measures" which he apprehended would "greatly lend to the universal spreading and permanent establishment of the Church of England in this Province ... and also most probably have an happy effect in removing that opposition to & prejudice against the Church in other Colonies of New England."

WHATEVER the mix in Wentworth's motivation, Eleazar Wheelock now felt free to start writing. The charter William Smith had drafted in 1746 for the College of New Jersey served as his basic guide. He adopted its general style and form, copied several passages verbatim, and altered others only slightly before including them in his own draft.* Using Smith's charter as a model solved a number of technical difficulties, but it left Wheelock's greatest dilemma unresolved. Somehow he had to produce a document which convinced the English trustees they should continue to pay his bills, which satisfied Governor Wentworth, and which left his personal influence in school affairs uncompromised. That he succeeded in accomplishing much of this is a real tribute to his political acumen.

Take, for example, the way Wheelock dealt with the complex problem of institutional control. He started with the assumption there would have to be both English and colonial trustees, and that he would serve among the latter as president of the school. What, however, specific authority should the English trustees have? How should he deal with Wentworth's expressed desire to have a number of Anglicans on the American board? Finally, and this depended in part on his answer to the previous question, what should be his own relationship to the colonial trustees.

Wheelock's thinking on the English Trust went through three distinct stages. He wrote into the first charter draft a set of provisions which duplicated the present arrangement: the Trust would share the authority with the American group for selecting future presidents. Then he had second thoughts. Perhaps he should follow Smith's original advice to give the overseas group nothing but the right to solicit funds. Dartmouth, Thornton, Keen and their associates, of course, would protest, but he might be able to mitigate their protest by offering a different form of recognition. Wheelock then turned to Wentworth for help. "I have been making some attempt to form a charter," he wrote on June 7, "in which some sort of respect may be shown to those generous benefactors in England who have condescended to patronize this school. And I want to be informed .. . whether your Excellency have Power and whether you think it consistent to make the Trust in England a distinct corporation ..." Wheelock, however, never found out whether a separate incorporation would appease his benefactors, for the Governor rejected the idea.

The draft Wentworth eventually signed reflects the final stage of Wheelock's thinking. He decided the trustees should be "vested with all that power therein which can consist with their distance from the [school]," which meant, in practical terms, no power at all (section 9). He eliminated their role in choosing future presidents and did not acknowledge their desire to have some control over expenditures. To show the "respect" he felt necessary, Wheelock did several things. A lengthy passage describing their past services was included (sections 2 and 3). The charter made it perfectly clear the English Trust had been given legal authority to determine the new school site, and had of its own free will selected western New Hampshire (sections 4 and 6). Wheelock also used the charter to explain why he considered a legal incorporation necessary, although he was careful not to mention the Trust's opposition to such action (section 7). Finally, Wheelock promised that he and his successors would "transmit to the Right honorable, honorable & worthy Gentlemen of the Trust in England ... a faithful account of the improvements & disbursements of the several Sums he shall receive from the Donations & bequests made in England through the hands of said Trustees & also to advise them of the general plans laid & prospects exhibited..." (section 32). The good doctor must have known he risked a great deal by treating the trustees in such a cavalier manner. But by now he had become accustomed to taking risks.

Determining the composition of the American group of trustees proved an even more troublesome task. Wheelock wanted simply to add Wentworth to the list of members already appointed in his will. It is not difficult to understand why. The list included the following men: his son Ralph; the Reverend Benjamin Pomeroy who was a classmate of Wheelock's at Yale, his brother-in-law, his most intimate friend, and a fellow New-Light (evangelical) clergyman; the Reverend William Patten, a Harvard graduate who had married Eleazar's daughter Ruth and also supported New-Light theology; another evangelical cleric from Connecticut named James Lockwood; the English Trust's candidate to succeed Wheelock, Samuel Kirkland; the Reverend Thomas Pitkin who had three desirable attributes - a Yale degree, New-Light sentiments, and wealth; William Pitkin, the Deputy Governor of Connecticut and Thomas's father. Wheelock knew he would encounter little difficulty with the trustees if his wishes were implemented. To maximize that possibility he wrote a long letter to Langdon suggesting the English Trust would be offended by any other arrangement. Wheelock also explained it would be convenient to have Connecticut rather than New Hampshire trustees, since the former were more knowledgeable about Indian affairs. Wentworth - assuming he saw the letter - probably found the arguments a bit strained.

The first completed draft of the charter reflected Wheelock's aspirations. The Board was to include Wentworth, Wheelock himself, the seven men appointed in his will, and still another Connecticut minister, this one a former student at the charity school; total membership could never exceed twelve. Soon after he learned the English Trust had selected western New Hampshire, Wheelock sent Nathaniel Whitaker and Ralph to Portsmouth with a copy. They returned with a frightening report. Wentworth, according to the two men, wanted the Bishop of London made an ex-officio member of the American board as well as the most powerful member of the English Trust. The Governor may also have demanded that the number of dissenting clerics appointed as trustees be reduced, and the number of New Hampshire residents increased.

Wheelock's response was dramatic, yet controlled. First he asked Smith (indirectly, because the barrister had become too ill to handle correspondence personally) whether any chance of a New York incorporation remained. Next, even before an answer arrived from New York, he decided to test Wentworth by threatening to "choose another situation" unless the Governor changed his mind. The threat - albeit couched in polite terms - came at the end of a letter in which Wheelock explained that tensions between the colonies and the mother country made the Bishop's appointment impolitic. Finally, Wheelock asked Colonel Alexander Phelps to negotiate a compromise with Wentworth. Among Phelps' qualifications were his patience and amiability (qualities both Whitaker and Ralph Wheelock lacked), his Anglicanism, and the fact he had been the husband of Wheelock's eldest daughter for the past seventeen years.

Phelps managed the affair quite well. Soon after he delivered Wheelock's letter Wentworth wrote back that there had been "an important misunderstanding of my proposal conveyed to you." He did insist the Bishop of London be invited to join the English Trust but wanted him there only to answer critics who claimed the "benevolent Charities" would be "applied merely and exclusively to the advancement of sectaries and particular opinions, with a fixed view to discourage the Established Church of England." The Governor, in addition, felt the school would be more secure if three New Hampshire public officials became trustees. Wheelock reluctantly accepted the compromise. Meanwhile Phelps discussed the board membership with Wentworth and other leading Ports-mouth citizens. The amended charter appointed twelve men (section 13). Samuel Kirkland and Ralph Wheelock were eliminated from Wheelock's original list; they seemed the most expendable, since the former had been selected only to please Keen and the latter had become physically and mentally ill. Four new names appeared: Theodore Atkinson, an aging merchant chosen less for his interest in education than his wealth and lack of heirs; a second well-to-do Portsmouth Anglican named George Jaffrey; Daniel Peirce, a dissenter on good terms with New Hampshire's political oligarchy; and Peter Gilman, a member of Exeter's leading family. All four men held high positions in the provincial government. Their generous gifts to the school undoubtedly helped Wheelock tolerate the one additional charter adjustment Phelps had been forced to accept, a clause obligating the trustees to fill future vacancies so the membership included eight New Hampshire residents and seven laymen (section 27).

Wheelock did not have to compromise on the matter of his personal relationship to the American trustees. From the beginning he insisted he be allowed to choose his successor as president, and nobody challenged him (section 20). Furthermore, as it became increasingly evident the Trust would contain men he neither knew nor controlled, Wheelock added provisions limiting its authority. The charter left him free to postpone the first meeting of the trustees a full year, and to select the time and place of that meeting (section 12).* The first draft said nothing about who should run the school between the "ceasing or failure" of a president and the choice of a successor by the trustees. Sometime during 1769 Wheelock added a clause giving the Senior Professor, assuming he served as a trustee, that responsibility (section 22). Wheelock also probably engineered the two-year delay before restrictions on new trustee appointments went into effect (section 27). Wentworth and his advisers accepted all this willingly. They cared about the school's long-term development, and since the project would flounder without Wheelock's direction it seemed wise to let him have his way on small matters.

THUS the ambitious Connecticut minister maneuvered with a high degree of success to shape a pattern of institutional control which would leave him reasonably independent in managing school affairs. Wheelock manifested political sensitivity in other ways too. He faced a potentially awkward situation in attempting to define the purpose of the school. The English Trust had to be assured their funds would be employed only for the educa- tion of Indians, while the people of New Hampshire, including Governor Wentworth, expected the school to supply local ministers. Wheelock himself planned to emphasize something quite different. The Lebanon experiment had originally been organized on the assumption that natives, after a lengthy period of instruction in Christian values (Wheelock once wrote of a pupil: "I have taken much pains to purge all the Indian out of him"), would return as missionaries to convert their brethren in the wilderness. The plan didn't work. For reasons much more apparent to modern men than to eighteenth-century divines, the Indians who went back usually reverted to their old tribal ways, and those who did not proved ineffective in spreading Christian doctrine. Wheelock therefore decided to take another tack. He would educate white missionaries and have them work either independently or with educated Indians. The policy had been partially implemented in Lebanon; the move to New Hampshire (as well as the involuntary loss of his Indian students) presented a golden opportunity to move still further in that direction.

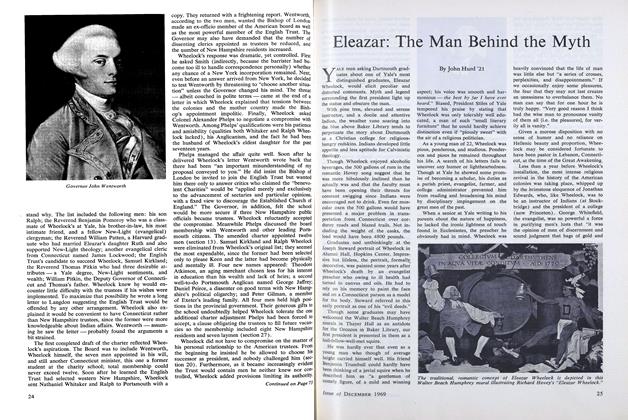

In writing the charter Wheelock kept his own intentions pretty well hidden. They were not mentioned in the first draft and appear in the final version only as a clause added to the section copied from the New Jersey charter defining the Corporation's powers; even then the term "English" missionaries was not used (section 15). Instead Wheelock wrote what he knew his benefactors - both American and English - wanted to hear. One passage openly admitted that his school might be "enlarged & improved to promote Learning among the English & be a means to supply a great number of Churches & Congregations which are likely soon to be formed in that new country ..." (section 5). Wheelock manifested his awareness of the English Trust's expectations twice. The clause included to satisfy his New Hampshire audience not only came after one stating the upper valley location "would be as convenient as any for carrying on the great design among the Indians," but began with the disclaimer "and also considering that without the least impediment to the said design... The formal statement of purpose (section 11) made explicit Wheelock's continued commitment to the goals Occom and Whitaker had so successfully advertised. It read: "for the education & instruction of Youth of the Indian Tribes in this Land in reading, writing & all parts of Learning which shall appear necessary and expedient for civilizing & christianizing Children of Pagans as well as in all liberal Arts and Sciences; and also of English Youth and any others." There can be no doubt Wheelock gave a good deal of thought to the potential effect of these words. In the first charter draft, which gave the English Trust the same powers it held under the existing deed, the passage read "for the education & instruction of Youths of the English and also of the Indian Tribes ..."

Wheelock handled two final matters with equal attention to their potential effect. One involved the type of institution to be established. For a variety of reasons, the ambitious educator wanted to found a college. He had, in fact, already organized a "collegiate branch" of the charity school in order to keep under his personal care those students who wanted degrees; previously they had been shipped off to Yale or Princeton. The idea, however, was one Wheelock dared not push too aggressively. The English Trust certainly would object - after all, Indians didn't need college diplomas— and earlier negotiations with Wentworth had been conducted on the assumption that Wheelock intended only to move his school. The founder of Dartmouth College handled the problem as gingerly as possible. The word "academy" appeared throughout the charter draft Ralph Wheelock and Nathaniel Whitaker carried to Portsmouth in August. Yet, Wheelock made it abundantly clear he wanted a college. The fact he had used the College of New Jersey charter as a model indicated this, as did his inclusion of a passage giving the "academy" diploma-granting privileges traditionally associated only with institutions of higher learning. To make certain Wentworth got the message, Wheelock added a postscript to the note he sent informing the Governor the draft was finished and would soon be delivered. "Sir," the postscript read, "if you think proper to use the word College instead of Achademy in the Charter I shall be well pleased with it." Wentworth probably registered some surprise when he saw the note, but complied: a college would fit with his plans even better than an academy.

The second involved naming the college. Wheelock didn't mention the subject until he had some way of assessing the political advantages which might accrue from his decision. In late October - after agreement on the Bishop of London had been reached - he felt ready to move. The last paragraph of the letter announcing his acceptance of Wentworth's terms began: "And if your Excellency shall see fit in your Wisdom and goodness to compleat the Charter desired, and it will be the least satisfaction to you to Christian the House to be built afteryour own name, it will be exceeding grateful to me." That same day, however, Wheelock informed Phelps he had decided not to call it Wentworth College because his "Obligations in point of Gratitude to the Earl of Dartmouth" were great and he conceived "that some advantage on that side of the Water might accrue by manifesting my desire to do him honor." Phelps, who was about to return to Portsmouth, received rather ambiguous instructions to seek the advice of others if he thought "it may bear his Excellency's Name to better advantage." Wheelock's intentions were perfectly clear: he would honor Wentworth if necessary, but he preferred to begin mending fences in England.

Subsequent events suggest that Wheelock had assessed the situation perfectly. Wentworth raised no objections, for he too wanted to get as much political benefit out of the charter as possible. It is impossible to measure the impact of honoring Lord Dartmouth on the English Trustees, but there can be no doubt Wheelock needed "some advantage on that side of the Water." The Trust members, after Wheelock finally screwed up his courage and sent them a copy of the charter, were furious. Keen wrote that Dartmouth, Thornton, and the other trustees thought he had taken "a very wrong step" and saw "clearly that by the affair of the charter the trust here is meant to be annihilated"; Thornton, who later gave large sums of money to the college, commented there was "too much worldly wisdom" in the document. But despite their objections, the trustees continued to pay Wheelock's bills. They demanded only that he use their funds solely for the education of Indians. Wheelock complied by moving the charity school to New Hampshire and maintaining it - at least for accounting purposes - as a separate institution.

In any case, the naming of the college ended negotiations with Wentworth. Final arrangements were delayed by the death of trustee Theodore Atkinson's wife, and perhaps also by the Governor's marriage to Atkinson's recently widowed daughter-in-law, Frances. The official signing took place on December 13, 1769. Wheelock could hardly contain himself. "Governor Wentworth," he informed a friend, "has granted me everything material I have asked of him . . . [the charter] is thought to be the most generous of that Nature upon the Continent & it is without any Clogg or disagreeable appendage." He did not elaborate on his role in "ye affair."

* Most quotations in this article are from letters and papers in the Dartmouth College Archives. I have also relied heavily on Frederick Chase, A History of Dartmouth College and the Town of Hanover,New Hampshire (to 1815), and Leon Burr Richardson, A History ofDartmouth College.

* A copy of the Dartmouth College charter appears as an appendix to this article. For convenience of reference, the charter has been divided into consecutively numbered sections. The following sections are almost exact replicas of passages in the College of New Jersey Charter. 12, 14, 15, 17, 21, 23-26, 28-31, 33-35. Wheelock also copied parts of Sections 13, 16, 18 and 19 from Smith's document.

* This proved to be important. Wheelock, Wentworth and several other interested parties wrangled several months over where the college would be located. The trustees did not meet until Wheelock personally selected Hanover, moved his family and students there, and began to construct buildings. Peter Gilman was the only New Hampshire resident to attend the first trustee meeting.

William Smith, who drafted Princeton's first charter, gaveinfluential advice to Eleazar Wheelock in "ye affair."

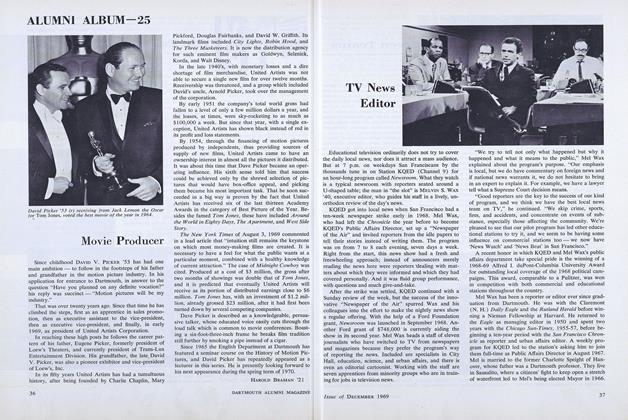

Draft of a letter to Governor John Wentworth, dated March 13, 1769, in which Wheelock raised the question of the Governor's authority to grant a charter entirely on his own. Wheelock had second thoughts about this approach and did not send it.

Governor John Wentworth

First charter draft showing the place where Wheelock, mindful of the expectations of the English Trust, reversed the order inwhich "Youth of the Indian Tribes" and "English Youth" were mentioned in stating the educational purpose of the new college.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEleazar: The Man Behind the Myth

December 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureTHE WHEELOCK SUCCESSION

December 1969 -

Feature

FeatureTV News Editor

December 1969 -

Feature

FeatureMovie Producer

December 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Article

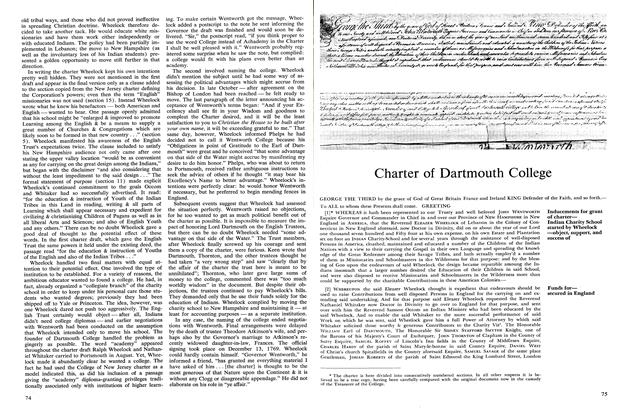

ArticleCharter of Dartmouth College

December 1969 -

Article

ArticleWith the Big Green Teams

December 1969

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryCOMMENCEMENT

June • 1985 -

Feature

FeaturePost What?

DECEMBER 1998 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Nov/Dec 2007 By Kristin Brenneman '97 -

Feature

FeatureMore than a beast, Less than an angel

October 1974 By PETER A. BIEN -

Feature

FeatureSCHOOLMARMS, GRAMMARIANS and ANARCHISTS

MARCH 1959 By ROBERT S. BURGER -

Feature

FeatureEverything But Little Dogies

April 1960 By WARREN BLACKSTONE '62, PETE BOSTWICK '63