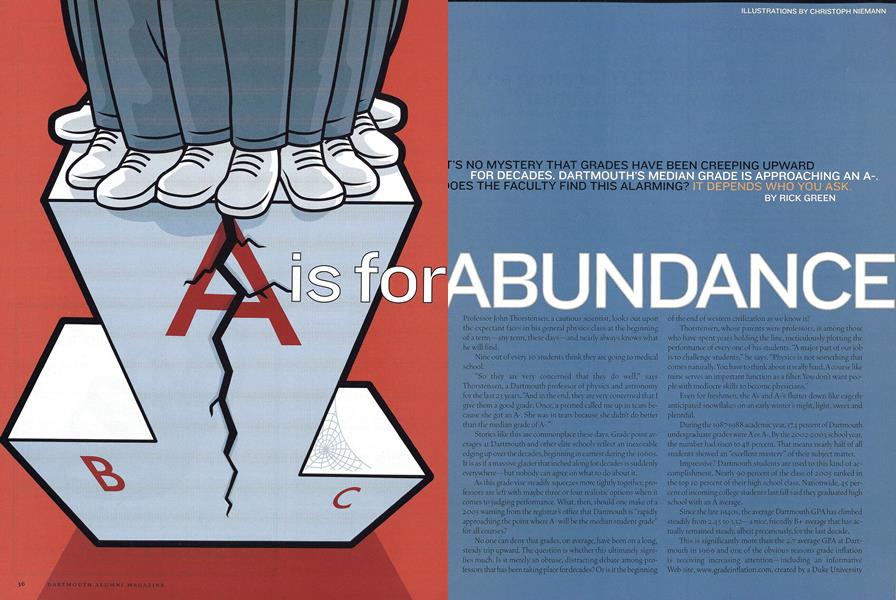

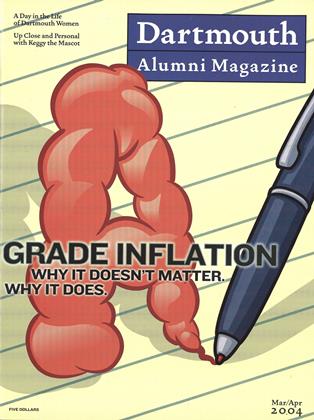

A is for Abundance

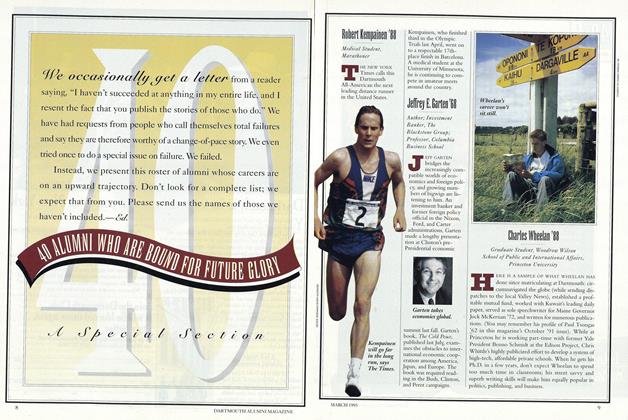

Dartmouth’s median grade is approaching an A-. Does the faculty find this alarming? It depends who you ask.

Mar/Apr 2004 RICK GREENDartmouth’s median grade is approaching an A-. Does the faculty find this alarming? It depends who you ask.

Mar/Apr 2004 RICK GREEN'S NO MYSTERY THAT GRADES HAVE BEEN CREEPING UPWARD FOR DECADES. DARTMOUTH'S MEDIAN GRADE IS APPROACHING AN A-. OES THE FACULTY FIND THIS ALARMING? IT DEPENDS WHO YOU ASK.

Professor John Thorstensen, a Cautious cientist, looks out upon the expectant faces in his general physics class at the beginning of a term-any term, these days-and nearly always knows what he will find

Nine out of every 10 students think they are going to medical school.

"So they are very concerned that they do well," says Thorstensen, a Dartmouth professor of physics and astronomy for the last 23 years. "And in the end, they are very concerned that I give them a good grade. Once, a premed called me up in tears because she got an A-. She was in tears because she didn't do better than the median grade of A-."

Stories like this are common place these days. Grade point averages at Dartmouth and other elite schools reflect an. inexorable edging up over the decades, beginning in earnest during the 1960s. It is as if a massive glacier that inched along for decades is suddenly everywhere-but nobody can agree on to do about it.

As this grade vise steadily squeezes more tightly together, professors are left with maybe three or four realistic options when it comes to judging performance. What, then, should one make of a 2003 warning from the registrar's office that Dartmouth is "rapidly approaching the point where A- Will be the median student grade" for all courses?

No one can deny that grades, on average, have been on a long, steady trip upward. The question is whether this ultimately signifies much. Is it merely an obtuse, distracting debate among professors that has been taking place for decades? Oris it the beginning of the end of western civilization as we know it?

Thorstensen, whose parents were professors, is among those who have spent years holding the line, meticulously plotting the performance of every one of his students. "A major part of our job is to challenge students," he says. "Physics is not something that comes naturally. You have to think about it really hard. A course like mine serves an important function as a filter. You don't want people with mediocre skills to become physicians."

Even for freshmen, the A's and A-'s flutter down like eagrly anticipated snowflakes on an early winter's night, light, sweet and plentiful.

During the 1987-1988 academic year, 37.4 oercent of Dartmouth undergraduate grades were A or A-. By the 2002-2003 school year, the number had risen to 48 percent. That means nearly half of all students showed an "excellent mastery" of their subject matter.

Impressive? Dartmouth students are used to this kind of accomplishment. Nearly 90 percent of the class of 2005 ranked in the top 10 percent of their high school class. Nationwide, 45 percent of incoming college students last fall said they graduated high school with an A average.

Since the late 1940s, the average Dartmouth GPA has climbed steadily from 2.45 to 3.32-a nice, friendly B+ average that has actually remained steady, albeit precariously, for the last decade.

This is significantly more than the 2.7 average GPA at Dartmouth in 1969 and one of obvious reasons grade inflation is receiving increasing attention-including an informative Web site, www.gradeinflation.com created by a Duke University professor. Nowhere has the topic attracted more notice in recent years than at Harvard, where the propensity to bestow top honors recently fueled a college-wide re-examination of grading. Faculty there three years ago approved changes that are expected to tighten grading policies. It may be too early to draw any conclusions, but today there are signs of grade deflation in Cambridge, with the number of As and A-'s edging downward amid efforts to cut back on the number of honors graduates.

www.gradeinflation.com

More recently, Point Park University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, docked the pay of six faculty members, including two tenured professors, for giving out too many A's. Each professor lost $1,000 in merit pay. This came on the heels of the administrations repeated urgings to not inflate grades.

The precipitous rise in GPAs during the 1960s and 1970s has been widely blamed on the Vietnam War and the desire to keep students in school and out of the draft. Then came the go-go 1980s and those even more cutthroat 1990s, where grades, career anxiety and material gain seemed to morph into one giant, careening SUV.

At its worst there is "a kind of tacit agreement between students and faculty," explains James B. Murphy, an associate professor in Dartmouth's department of government. "Grade inflation makes both of their ideas more convenient. It's advantageous for students if their feelings don't get bruised. And for faculty its a lot easier to give higher grades," says Murphy. "You pretend to work and we pretend to grade you."

Provost and professor Barry Scherr sees professors who are under increasing pressure from students, and it isn't always without cause. "Nowadays one or two poor grades seems to wipe you out because everyone else is up so high," he says. "It feeds grade consciousness."

To an outsider, this grade inflation and compression may seem startling, even slightly alarming. On campus, it's just the way things are.

"To get something below a B is unlikely," says Bente Shoen '02, who wrote a comprehensive series of articles on grade inflation for The Dartmouth her senior year. According to Shoen's research, there is a threshold that runs across College departments.

"To jump from an A- to an A is a huge step," Shoen says. Her research also revealed, not surprisingly, a distinction between science and humanities departments when it comes to grading. "The science disciplines seem to think it is more important to distribute grades in a certain way," says Shoen, now a warehouse supervisor in Massachusetts. "And professors in the humanities classes don't seem particularly concerned about grades."

For some faculty members—including many outside the humanities- the grade inflation debate is a diversion from Dartmouth real mission of teaching and learning. "If grades have migrated up, what difference does it make?" says dean of the faculty Michael Gazzaniga '61, the David T. McLaughlin Distinguished Professor of Psychological and Brain Sciences. "You still have to master the content."

Gazzaniga directs the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience. He can tick off the names of Dartmouth undergraduates doing brain research once reserved for those at the pinnacle of their careers. "I don't think there's a significant difference [in grading] between now and when I went here," he says. "The world will tell you real fast if you are competent or not."

In one corner of this debate are the principled scientists, who've never really abandoned their love of grading on a curve. In the other corner are the generalists, those writers and artists who see grades— and distributing them along a tidy curve on either side of some mid- point—as inane.

In between, there's a lot of mushy gray. Even if everybody is getting A-'s and B+s, the argument goes, is there any reason to think students aren't working just as hard, learning just as much?

"Grades at Dartmouth have certainly gone slowly but steadily upward," notes Noel Perrin, a former chair of the English department and now an adjunct professor in environmental studies who proudly thumbs his nose at all the grade inflation talk. "They should have gone steadily upward because we have such talented men and women."

Perrin and others say it is also unfair—and illogical—to try to equate the likes of an entry-level physics class with, say, an advanced religion class. "The difficulty is when you come to courses such as mine and everybody wants to be there and everybody is interested in the material," says religion professor Susannah Heschel. "What do I do? You want to be liked and you want to be judged a good teacher. You don't want to get a reputation of being too hard or too difficult. Every professor I know complains about having to grade. It is hard to be fair when you're reading 50 papers. There is, of course always the sense that it would be so easy to give all As."

Unlike many other schools, Dartmouth has taken a laudable, if incremental, step to counterbalance the inexorable march toward As for all. In 1994 the faculty voted to tack on the median grade of a class to a students transcript, thereby placing the grade—inflated or not— in context. The practice remains relatively rare among elite schools.

But some see even the median grades as inflated, because students performing poorly in a tough course frequently take advantage of Dartmouth's generous class withdrawal policy. For example, about 10 percent of students always drop Lindsay Whaleys "Linguistics I" course, pushing up what would have been a lower median grade.

"For me, 10 percent is going to raise the median grade by a step, from a B- to a B," explains Whaley, an associate professor of classics and linguistics. "What that hurts is the students who are really doing well in that class. I would like people to take seriously the written description of grades. Let's remind ourselves what grades are for and what we are trying to do with them."

Dartmouth's "scholarship ratings" (see "Deciphering Grades," right) outline any one of 10 grades a student may receive, leaving it up to individual faculty to make the call. A "C" is described as "acceptable mastery of course material."

In 2002 James Baehr '05 concluded in a Dartmouth Review article that the striking rise in the number of As and B's in the last century coincided with a move away from a philosophy of distributing students along a curve based on a median score. He argued that basic grading standards—outlined in the College's weighty Organizations,Regulations and Courses handbook, are routinely ignored.

"There is no way we can go back. The whole education system has moved in the same direction together," says Baehr, who admits his conservative outlook may be slightly out of step with the rest of campus. "Students just want to get the best grades they can. There is an incredible amount of pressure."

History professor Bruce Nelson, who has taught at the University of California and Middlebury, is more blunt. "Today a B is bad and C is a disaster," he says. "The thing that bothers me is the attitude: 'If I get a B+ you are screwing me.' " In other words, students expect As. 'And then there is resentment if they don't get what they expect," says Nelson.

Among hardy cynics in the sciences there is an old joke: You're critically injured in a car accident in some strange town, lying half dead in an obscure emergency room and staring up into the eyes of the physician on duty at 3 a.m. You realize he's one of your not- so-long-ago students and think: Was that a gentleman's B+ I gave himback in cell biology?

"Some students, if they get an A- or B+, it's over," says Michael Perry '03. "If I'd gotten a C+ in something that would have been a really big deal for me. I'd have thought I wasn't doing very well. [Inflation] is self-perpetuating. Professors don't want to give poor grades and have students not get into grad schools or get jobs."

This, of course, is what outrages those who feel they are holding back the bulging dike. "If everybody is getting an A, how do you say who is doing great?" asks Mark A. McPeek of the department of biological sciences, where the median GPA is about a B and among the lowest of all majors at Dartmouth.

"We set policy," says McPeek. "We shoot for a median grade that is a B-. We figure the average student should be getting a B-. We think it is pretty important that when students get a grade it actually means something. What disturbs me is that the [median] grade for first-year students is A-. I think it should be in the B to B- range. We are trying to maintain standards in these courses and it becomes very difficult." He cites the late withdrawal policy as a big part of the problem.

While McPeek seems to make the traditional grading curve seem logical, the issue gets thorny again when viewed in the context of intersecting academic priorities, educational philosophy and student ability.

"The departments with lower grades are the ones where you are dealing with hard information, where the huge differences that exist in the capabilities of our students are difficult to mask," notes history professor Jere Daniell '55, who arrived in 1964 and retired last year. He says it isn't an issue where broad generalizations about the fate of higher education can be tossed about or lumped in with assessments of our declining pop culture.

"I did not give a student who tried less than a C-. Since almost all students try, the floor is a C," says Daniell. He gave D's when he first arrived at Dartmouth but didn't by the time of his retirement. "The grade of D now is a punitive grade," he says. "My attitude was that if Dartmouth admitted them, it was my job to educate them."

Typical in the humanities is religion professor Susan Ackerman '80, who says she has often thought about grades during her 13 years at Dartmouth. "But this is [only] the second conversation I've had about grade inflation," says Ackerman, who also serves as co-chair of the women's and gender studies program.

"It's certainly true that average grades in humanities and social sciences are higher," she says. But there's good reason for that. "These [science courses] play an important weeding out function. If in the religion department we set a mean grade at B- or C+, our enrollments would plummet to the point where we would be in trouble."

Few go so far as math professor Dana P. Williams. His general point haunts the entire debate: We know our students are among the best, so why penalize them?

"Grades now have become practically meaningless," says Williams. "The basic problem is we have good students and we don't particularly want to damage them. They work hard and you want to reward them. I suppose it's a lack of courage on our part," he adds, acknowledging the pressure faculty feel not to derail Dartmouth students from their destiny to succeed.

Yikes, Professor Williams. So what does work?

Williams and others, such as Provost Scherr, say the very top grades still provide a sense of who the stellar performers are: students who earn As over a series of terms. For others, standardized test scores become more important, as do personal recommendations and "citations." These increasingly popular addendums to a student s transcript allow a professor to outline the "particularly favorable impressions" a student makes "that are not indicated adequately by academic grades," according to College policy.

Numerous professors and students also point out the difficult leap from A- to A as evidence of a line that remains sacrosanct.

"I have a complicated relationship with grades. Sometimes I use them as a carrot, sometimes as a stick," says English professor Ivy Schweitzer. 'An A has to be really special. A student has to do something I didn't expect."

The average GPA for English courses for 2002-2003 was 3.4, lower than numerous other non-science subject areas. Still, all these As raise a fundamental question, just as rampant monetary inflation makes a single dollar seem fairly hollow.

"If the grades aren't giving signals, then what happens?" asks government professor William C. Wohlforth. "The more they are bunching up at the top, the more guesswork about what students are like. Wouldn't it be a much better world if an A- or an A really conveyed information about a student?"

Many at Dartmouth seem content that grade inflation is far worse elsewhere—and that any solution could well be far more painful than enduring a compressed grade scale. Some of Dartmouth's leading thinkers also maintain that a glut of higher grades are just that, offering very little insight into what is happening on campus.

"You cannot tell a difference between these kids" by merely looking at a transcript, acknowledges Gazzaniga. Still, he sees no signs of any seismic changes at work. What's so surprising, he asks, about tougher grading in math and science, courses that require a clear understanding of an objective body of information?

"Where it really comes to fruition is graduate school. It doesn't take long to figure out who is smart there," he said.

Grade inflation, for now, remains an accepted—even desir- able—state of affairs.

"You can see why it's happening. It's hard to see what would make it not happen," says Perry, a philosophy major now in graduate school. "When students look at it, it's like, 'I wish it wasn't there, but I'm really glad it is.'"

"If EVERYBODY is getting an A, how do you say who is doing great?" -BIOLOGY PROFESSOR MARK A. MCPEEK

"We have good STUDENTS and we don't want to damage them." -MATH PROFESSOR DANA P. WILLIAMS

RICK GREEN is a reporter for The. Hartford Courant He lives in WestHartford, Connecticut.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Day in the Life

March | April 2004 By JONI COLE, MALS ’95 -

Feature

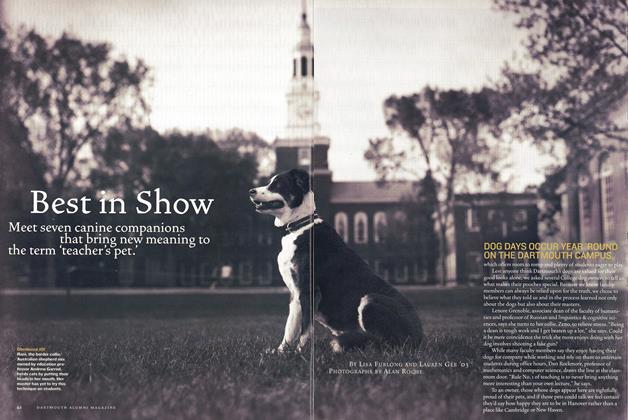

FeatureBest in Show

March | April 2004 By Lisa Furlong and Lauren Gee ’03 -

Article

ArticleSeen & Heard

March | April 2004 By MIKE MAHONEY '92 -

Faculty Opinion

Faculty OpinionSaturate, Don’t Isolate

March | April 2004 By David C. Kang -

From the Dean

From the DeanThe Fourth ‘R’

March | April 2004 By Michael S. Gazzaniga ’61 -

OUTSIDE

OUTSIDEAnimal Attraction

March | April 2004 By Ted Levin