In a bid for more intellectuals, the president launches a debate about Dartmouth's soul.

Moments after he assumed the presidency of Dartmouth College, James O. Freedman enunciated what may be the most important initiative he will take here. Students call his announcement, uttered last year during his inaugural speech, The Sentence:

"We must make Dartmouth a hospitable environment for those creative loners and daring dreamers whose commitment to the intellectual and artistic life is so compelling that they appreciate, as Prospero reminded Shakespeare's audience, that for certain persons a library is dukedom enough."

of the College's image. He countered the traditional Dartmouth joinerthe well-rounded, gregarious stu-dent with the loner. "We must strengthen our attraction," he said, "for those singular students whose greatest pleasures may come not from the camaraderie of classmates but from the lonely acts of writing poetry, or mastering the cello, or solving mathematical riddles, or translating Catullus."

His vision is a competitive one. Although Dartmouth ranked sixth among American universities in a recent poll of college presidents, the College is a last choice among most students who are accepted at Harvard, Yale or Princeton. Freedman wants Dartmouth to assume the lead. "In the next 20 years," he asked in an interview, "where are the very strongest faculty and the very strongest students going to want to be?"

The question poses an unprecedented standard for the College, according to Trustee Ira Michael Heyman '51, chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley. "Remember the song that goes: 'We wear the Dartmouth green and that's enough'? Well, what Freedman is saying is that it isn't enough."

Along with calls for more women, minorities and foreign students, Freedman's goal to add more intellectual cream to the student sauce has inspired the campus and alumni to do some soul-searching about Dartmouth's purpose.' What is the ideal student body? Is there a conflict between a college's elitist traditions and its obligation to develop leaders for a changing society? Does the growing diversity among students at the top schools threaten community feeling and collegial atmosphere?

If there ever were an ideal place to ask these questions, Dartmouth is it. It's hard to imagine a school with such deeply held traditions and such loyal alumni. Some of these traditions have resulted in a public image of students that President Freedman finds unfair.

The Dartmouth student of repute, according to Freedman, is "extroverted, gregarious, party-going, athletically oriented, overly prone to conformity, well-rounded, and intelligent but not intellectual." Such an image, he told the faculty last fall, "embodies a vestige of a style of collegiate life that we can no longer permit to reflect the Dartmouth of today."

Others on campus, however, say that there is more truth to the image than Freedman can admit publicly. "It is not a stereotype," maintains former Dean of Freshmen Margaret Bonz. "The image, by and large, is real."

Bonz's assertion appears to be borne out at least among a significant minority of students by a survey last fall of incoming freshmen at a group of highly selective colleges. The study, conducted by the American Council of Education, seems to reveal that many students come to Dartmouth to be reflected in its traditional image. While 92 percent of last year's incoming freshmen said they chose the College because of its academic reputation (compared with 83 percent at the other schools), fully 47 percent said Dartmouth's social reputation—the stereotype, perhaps, that President Freedman is against—drew them to Hanover. At other schools, only 29 percent cited social reputation as a deciding factor. Some 12 percent of Dartmouth freshmen said they came because they were recruited as athletes-considerably higher than other highly selective colleges.

Freedman clearly has no intention of replacing them all with intellectuals. In fact, he does not speak of "changing" the student body at all; rather, he says, his goal is to "enrich" it. "What college ought to be is a collection of talented human beings who are all very different from one another," he said in a recent interview. "I want to be sure that the applicant pool at Dartmouth is as wide a pool of talent with students of different kinds of aptitudes and aspirations and ambitions as possible."

Actually, Dartmouth already has an enviable reputation. Less than one applicant in five is admitted. This year Dartmouth received a record 10,250 completed applications. Of these, the College accepted 2,060 to end up with a freshman class of 1,100. "We are seeing a stronger applicant pool this year," Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid Alfred Quirk '49 said. The result was even keener competition.

Applicants are not the only ones doing the competing; Dartmouth works diligently to maintain its selective status. Admissions Director Richard Jaeger '59 puts a team of 16 officers on the road for six to eight weeks each fall. Most of them are assigned to geographic territories, although a Black admissions officer works specifically with minority students.

In addition, some 4,500 alumni volunteer for Admissions, interviewing candidates and extolling the College's glories. As the Dartmouth's front line in society, alumni form the College's largest group of recrui-ters—and certainly the most enthusiastic. "Ninety percent of the writeups by alumni are favorable," Quirk notes; for this reason, he says, the alumni interview alone rarely determines the decision.

Some faculty members invoking, perhaps, their own stereotype of Dartmouth graduates question whether alumni are capable of representing the College's changing admissions goals. "I still find [alumni] who are surprised at the fact that I teach at this institution," says Marysa Navarro, associate dean of the faculty for the social sciences and one of the first women to win tenure at Dartmouth. Anthropology Professor Hoyt Alverson frets that the "rhetoric of solidarity" spoken by alumni might turn off the less traditional applicants. "There is going to be a certain dissonance for the type of student President Freedman is trying to attract," he says.

Admissions Dean Quirk, on the other hand, thinks alumni are "verycapable" of selling today's Dartmouth. He says that is particularly true of alumni from the class of 1976 the first coed class forward. "We've got to get more women and minorities into the act," says Quirk. "If we are telling candidates that diversity is important, we've got to illustrate it with our alumni body."

The difficulty of achieving diversity can be seen in the mechanics. After the recruiting comes the hard part: the actual selection. The first reading of an application takes 15 minutes. That is not as short as it seems, for many of the applicants' credentials have already been boiled down into a shorthand used by Admissions people. After two such readings by a pair of officers, a large chunk of the applicant pool is either in or out. Those in the middle are discussed at so-called "roundtable" sessions involving members of the Committee on Admissions and Financial Aid and staff members.

A single number the academic index, or A.I. is calculated for every applicant. It reflects and gives equal weight to the candidate's performance on SATs and achievement tests as well as high school grades. An A.I. can range from a low of 60 to a high of 240. At Dartmouth, the average student admitted to the class of 1991 rated highly with board and achievement scores in the high 600s and a class ranking near the top.

Of course, the Admissions Office considers much more than grades and board scores. Applications are "flagged" or "tagged" with other shorthand information about the candidates. There are flags and tags for, among others, recruited athletes, Blacks, Hispanics, Asians, Native Americans, north-country rural applicants, foreign students, children of alumni or legacies, and V.l.P.'s.

The V.I.P. label, known to admissions insiders as "the money tag," is reserved for those applicants whose admission can be viewed as crucial to the institution's future an important political figure's son or daughter, say, or the offspring of a very major donor. "It means, if you are going to turn the kid down, don't do it with a form letter," explains former Admissions Dean Edward T. Chamberlain '36. "And if the kid is close, you give him the nod."

Other factors the Admissions Office considers include extracurricular activities ("Music professors sometimes sound like coaches in asking us for oboe and cello players," says Quirk) and where the candidate lives. Dartmouth is always looking for geographic variety; this year Admissions aimed for more students from big cities and fewer from the suburbs.

Dartmouth's 20-percent acceptance rate thus masks great differences in how groups of applicants fare. For example, the College admits 40 to 50 percent of the legacies who apply for admission, 38 percent of the Blacks and about the same percentage of the Native American applicants.

Naturally, Dartmouth is not alone in recruiting among minorities and high achievers. The College often accepts desirable applicants who are also being wooed by other Ivies. Hanover draws a paltry 13 percent of students admitted to both Dartmouth and Harvard; the rest go to Cambridge. "Nobody uses Harvard as a backup school," explains Quirk. Similarly, only 13 percent of joint admits choose Dartmouth over Princeton. Against Yale, the figure is a not much more encouraging 16 percent.

The statistics do not reflect students who selected Dartmouth as a first choice and were admitted under the "early decision" program in December—an option that the other three schools do not offer. Still, says Quirk, Dartmouth remains at a genuine disadvantage in name recognition compared to the Big Three. "All over the world, people can name three universities in the U.S., maybe four," he observes: "Harvard, Yale, Princeton and Stanford."

So how can Dartmouth compete with the other top schools? One technique, increasingly popular among the elite institutions, is to offer free trips to campus and special programs for academically superior high school students. Last year the College instituted a Presidential Scholars Program which gave high school intellectuals red-carpet treatment similar to that given recruited letes. Candidates were flown in and promised special seminars and access to the distinguished guests of the College who teach as Montgomery Fellows. According to Quirk, the program is already a success; about twice as many high-powered students are in the class of '92 as in the previous class.

To woo more top scholars in the long run, however, may require overcoming a chicken-and-egg problem. While supporters of Freedman's admissions initiative argue that a critical mass of intellectuals on campus will cause a shift toward serious academics college-wide, others believe Dartmouth must change first—before it can attract more significant numbers of intellectuals.

Freedman himself seemed to note this in his faculty address. "We need to make Dartmouth hospitable to the most intellectual and academic of students—and especially to women and members of minority groups and to make certain that the reality of our collegiate life fully reflects that hospitality," he said.

Feeling welcome is only part of the solution, argues Karen Avenoso '88, the College's newest Rhodes Scholar. "People come to Dartmouth with the potential to do a great many things," she says. "But because of certain institutions, practices and values, they quickly become mainstreamed. They fail to explore and develop their potential."

In her view, part of the problem stems from Dartmouth's being "such a group-oriented school. From our first day on campus we are grouped," she says: "on our freshman trip, in our class, on athletic teams, and, later, in sororities and fraternities." While she sees positive fallout from this phenomenon school spirit, camaraderie, warmth toward the institution "I also think we tend to lose a sense of who we are by ourselves," she says. "I think it discourages autonomous, independent thinking."

The result, she contends, is that students often buy into Dartmouth's "work hard, play hard" ethic. "Classroom work goes up to a certain point, and it stops. There's a boundary. It's as if the critical thinking that goes into your academic life can't extend into your social life ... So many people just go to parties and try to fit in." Students, she says, are afraid of being labeled "geeks" or "tools" for studying too hard.

Alverson's prescription: toughen up grading, revamp the Dartmouth Plan and abolish fraternities and sororities. "The existence of single-sex subgroups on campus is a cultural anachronism," he says. "It's part of the work hard, play hard polarity. I think they've got to go. Unless they go, all this talk about admissions is pointless."

Fraternities come under attack also from Dean of the College Edward Shanahan. "Before Freedman's vision can be realized," Shanahan predicts, "the Greek system will have to change." Some of those alterations have already begun, and he predicts that they will accelerate as more houses accept both men and women.

Shanahan joins Alverson in blaming the Dartmouth Plan in pari; for submerging the intellect. The plan encourages students to spend terms off-campus, and its four-term system limits the duration of a course to a relatively short ten weeks. "I think the staccato of the Dartmouth Plan does not allow students enough time to reflect," he says. "We have a very, very busy student body." On the other hand, the plan has numerous defenders among both faculty and students, who like the opportunity it gives for internships and foreign study.

The relatively new system does not explain Dartmouth's long tradition of welcoming the "joiner" over the "loner." Naturally, other schools have lost students whose singular interests have been out of synch with the campus. But more than most other institutions, the College has had a public reputation for being inappropriate for diffident intellectuals.

Robert Frost is a good example. Frost came to Dartmouth in the fall of 1892 filled with "expectations of literary things," he told the Alumni Magazine in a 1959 interview. On his first night in Wentworth Hall, upperclassmen imprisoned him in his dorm room by screwing the door shut. The poet took refuge from the raucous inter-class brawls of his day by taking frequent solitary walks through the woods surrounding Hanover. He withdrew from Dartmouth shortly after Christmas.

Stories of creative dropouts go back considerably farther. Another singular character, John Ledyard, also fled campus during his freshman year. Ledyard, a member of the Class of 1776, was a sensitive young man with an artistic bent who arrived in Hanover with bolts of cloth to make scenery and costumes for theatrical productions. "He went down to the Connecticut River, hollowed out a tree and sailed away, never to return," says College archivist Kenneth Cramer. Ledyard later won fame as an explorer, becoming the first white man to set foot on the Hawaiian islands.

Loners are not the only people who have sparked cries for change at Dartmouth. Freedman, like his colleagues in the rest of the Ivies, wants to see more minorities, women and foreign students admitted. This quest for diversity continues a trend that began in the 1920s, when Dartmouth first reached beyond the Northeast for students. It accelerated in the 1960s, when the elite schools began recruiting Blacks in unprecedented numbers.

Rather than discussing quotas for women and minorities, Richard Jaeger talks of "comfort zones" that approximate groups' representation in the U.S. population. "If our mission is to provide leaders and doers to society, we can't do it if all we have is WASPs here," he says. "We should aim to turn out a Henry Cisneros, say, or a Jesse Jackson, or a Gloria Steinem."

On the other hand, some argue that Dartmouth should be a strict meritocracy. "I think it compromises the integrity of the institution to consider sex or color," says Christopher Baldwin '89, former editor in chief of the Dartmouth Review, an independent student newspaper.

The momentum appears to be away from Baldwin's wishes. The Trustees' call last fall for "more substantial parity" between men and women was the first concrete manifestation of Freedman's quest for greater diversity. Female enrollment had been declining for three years after peaking at slightly more than 42 percent with the class of 1988. A greater effort to recruit women including a telephone campaign by Dartmouth students resulted in a record female freshman enrollment of 44 percent. "None of the schools is achieving 50-50," notes Jaeger. "All of us have been in the high thirties to low forties."

More women on campus "should change the climate here, and that will cycle back and lead to more applications from women," he predicts. In the meantime, Freedman hopes the Trustees' call will give recruiters an answer to future female prospects who bring up the College's macho image.

As with women, recruitment of Blacks has suffered from Dartmouth's image problems. Black enrollment fell sharply in the class of 1990, after conservative students demolished shanties that had been erected on the middle of the Green to protest the College's investments in companies that did business in South Africa. "It was not a good year," admits Jaeger, "but we are now getting back into the comfort zone." The class of 1992 includes 96 Blacks, or nine percent of the enrollment.

Other gains can be seen in the number of foreigners yet another admissions priority for Freedman. "Foreign students can play an important role in helping us to nurture an international dimension at Dartmouth," the president said in his fall '87 speech to the faculty. The College continues to fare poorly in comparison with Harvard, Yale and Princeton, but the number of incoming foreigners this year exceeds 50, up somewhat from 1987.

As Dartmouth's student body changes to reflect Freedman's vision, Dean Shanahan predicts that the stereotype will fade in the face of reality. But Shanahan warns that the College must never shed its legacy as a special place: "Every institution has its identity, and it should be very, very reluctant to shuffle off the core of that identity."

Some people think that is exactly what is at risk. "If it ain't broke, don't fix it," asserts Chris Baldwin, the former Dartmouth Review editor. "Dartmouth has found its niche in the Ivy League. It ought to be more comfortable with the way it is." But few observers doubt that Dartmouth has been changing for years, and that this relatively new status quo is impossible to maintain. When the campus shifted its social gears to make diverse groups feel more welcome, the Indian symbol became non grata, the alma mater was revised, and fraternities and sororities became subject to more stringent curbs.

The latest recruiting changes may disappoint some parents. When asked which group will come under pressure, Richard Jaeger points to the children of alumni as one likely area. "The percentage of legacies may have to shrink, especially as we see a stronger and stronger applicant pool. That's not to say we'll throw them to the dogs. It's just that we probably won't be able to stretch as much as in the past," he explains. In addition, "the bland but well-rounded individual may have a tougher time getting in," predicts Jaeger. "We'll be look-ing for some extra dimension or level of accomplishment."

Coaches, on the other hand, may benefit, according to Athletic Director Ted Leland. He claims that, in the long run, athletes will be attracted by the drive to enhance Dartmouth's academic reputation. "Take Harvard," he says. "They are very tough to beat in recruiting, and it is not because they offer a better athletic experience. It is because they are Harvard." (Several coaches, however, voice skepticism of Leland's point.)

Leland is the liaison between the athletic department and the Admissions Office. Twice a year, he and the coaches meet with Richard Jaeger to see "what kind of kids the Admissions Office will consider," Leland says. Jaeger's talk includes a recap of the Ivy League admissions rules. Rule number one is that no athlete will be admitted with an academic index under 161 unless there are "compelling nonathletic reasons." These can include racial or ethnic status, artistic talent, or a belief that test scores don't adequately represent the student's academic potential. "And every once in a while we pull a legacy through," Leland adds.

The second Ivy League rule mandates that, on average, recruited athletes for football, men's basketball and men's hockey must be within one standard deviation of the entire class's average academic index. As a practical matter, this means that the average A.I. of those recruited athletes who are admitted must be 184 (compared with 200 for the class as a whole). "The idea," says Leland, "is that athletes should be academically representative of their classmates." (This is known informally as "the broken leg rule": athletes should be able to make a contribution to a college even if they are injured.)

From time to time, the League makes exceptions. From 1984 through 1987, Columbia was permitted to admit up to six football players whose A.I.'s were below 161. The result: Columbia's freshman football team was undefeated last fall. "Their football team was a chronic loser, and one of the effects of being a loser was that they were unable to attract top students who were also good football players," explains Jeff Orleans, executive director of the Council of Ivy League Presidents.

Dartmouth has not needed this sort of break. Its coaches scour the country for top scholar-athletes during the off-season, and many of the prospects are brought to campus on sponsored visits paid for by Dartmouth alumni. If the athlete is persuaded to apply, his or her name is placed on a list that is sent over to the Admissions Office. Between 2,500 and 3,000 athletes are included on recruitment lists every year, according to Leland.

The process imposes strict discipline on the coaches. They are forced to rank each recruited athlete, from the best to the worst, on athletic ability alone. "Grades are immaterial. The best athlete the kid who would mean the most to your program is number one," explains Leland. "This gives the Admissions Office the clearest picture of who the talented athletes are." In football last year, for example, Coach Buddy Teevens '79 sent over 220 names, hoping that 110 would be accepted and that 55 would matriculate. In fact, 97 were admitted but 67 matriculated.

"It is a fluid process, with lots of back and forth," Leland says. "There are negotiations, but no arguments. If I get into an argument with Admissions, I'm going to lose. My coaches are going to lose. And this institution is going to lose."

Still, Leland takes strong exception to critics who oppose giving athletes special consideration. "The Ivy League started out as an athletic conference," Leland argues. "It is simply unfair to make Dartmouth students play ice hockey against bigger, stronger, faster, tougher kids 26 times a year, and not stand a chance of winning. It takes a toll on the human spirit, and it takes a toll on the institution. It is important that we not be chronic losers."

If Leland is right, and the admissions drive does not make the coaches' task more difficult, will the fundraisers fare as well? Freedman has stated that he would like to see a larger number of students go on to earn Ph.D.'s. How would that affect the College's endowment?

"Giving records reflect two things: salary and inherited wealth," replies Henry Eberhardt, director of the Alumni Fund. "Obviously, the average investment banker earns more than the average professor. But with a thousand people coming through every year, I don't think that all of a sudden they're all going to turn into professors."

Eberhardt notes that, during the debate over coeducation, many feared that women would donate less than men. "That has not been the case," he says. "We tracked the first few classes for a number of years, and the gifts were essentially identical." The fundraisers need not worry at

any rate, officials say, because the College's essential uniqueness will not be lost in the admissions changes. "I get the impression that some people think Dartmouth will be filled with nothing but cello players and late-night thinkers," says Dean Shanahan. "What the president wants to do is to enable that side of Dartmouth students that is reflective and intellectually vibrant to be more visible."

But therein lies the danger, warns Brett Matthews '88, co-founder of the student newspaper Common Sense. "What is the cost of raising the level of intellectualism on campus?" he asks. "Does Dartmouth have the resources to compete with Harvard, Yale and Princeton?"

Indeed, Dartmouth's higher academic aspirations reopen a debate that goes back a century and a half. Should the College act more like a university, stressing research and increasing the number of graduate degrees? "It is in the cards," says Trustee Heyman. "We've got to have more graduate programs. Especially in the sciences, it's a constant fight to hold onto people, to attract the really smart, creative thinkers who are also good teachers." In Heyman's view, as long as Dartmouth maintains "a couple of internal rules" no sections taught by gradscidents, an easily accessible faculty "why not do it?"

The notion likely sticks in the craw of those who revere the moving paean by Daniel Webster '01 to the "small college." That image may be little more than nostalgia at any rate; it is difficult to deny that Dartmouth, with its three professional schools and already-long roster of graduate programs, crossed the line between college and university a long time ago. But there is an intimacy to the place, with its isolated beauty and tightly knit alumni and emphasis on undergraduate education, that still vibrates with a collegiate tone. All of which presents Dartmouth's great challenge: it must aspire to the top of academic excellence without losing its essence.

Freedman, for his part, welcomes the debate. "I think we're going through a sorting-out process now, a process in which we're filling up a large volume with reactions and responses, and that's a very healthy thing for this institution," he says. "I think self-examination is good for the institution's soul no less than it is for an individual's soul."

Exactly what constitutes the institution's soul may be part of the debate. But few could deny that the core of that spirit, the thing that is Dartmouth, lies somewhere in the midst of a changing student body.

Not every new student will be an Einstein, Freedman says, but the overall mix will be "enriched."

Alfred Quirk '49 Dean of Admissions and Financial Aid

athEdward Shanahan Dean of the College

Ted Leland Athletic Director

Richard Jaeger '59 Director of Admissions

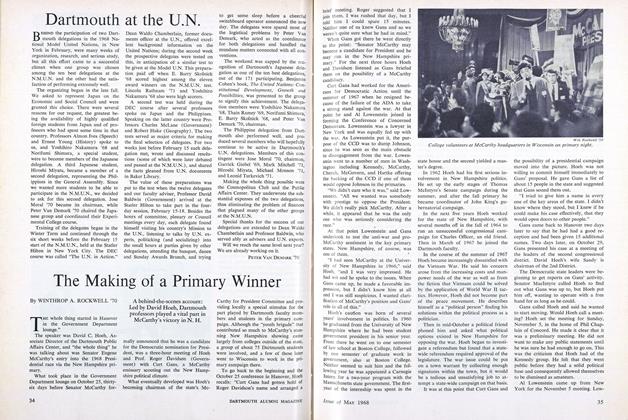

With the help of the Gospel Choir, Black recruiting is up.

The most elite schools eschew well-rounded applicants in favor of a diverse body of talented students.

"All over the world,people can name threeuniversities in the U.S.,maybe four: Harvard,Yale, Princeton andStanford."

"The president wants toenable that side ofDartmouth students thatis reflective andintellectually vibrant to bemore visible."

"If I get into anargument withAdmissions, I'm going tolose. And this institutionis going to lose."

"If oar mission is toprovide society's leaders,we can't just haveWASPS here:'

Victor F. Zonana '75 is a reporter with the San Francisco bureau of the Los Angeles Times. He revisited Dartmouth for two weeks last winter.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom America's Lost Cohort, the Shards of Souls

September 1988 By David R. Boldt '63 -

Feature

FeatureIn the Galactic Search for Intelligence, We May Find Ourselves

September 1988 By Jack Baird -

Feature

FeatureIS DARTMOUTH STILL DARTMOUTH?

September 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

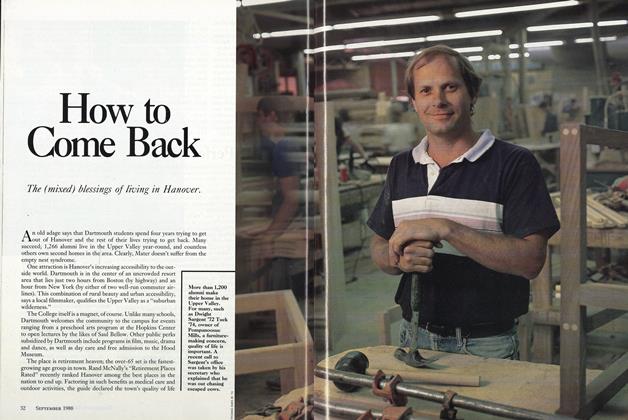

FeatureHow to Come Back

September 1988 -

Sports

SportsFall Sports Preview

September 1988 -

Article

ArticleRush Delayed

September 1988 By Jack Steinberg '88

Victor F. Zonana '75

Features

-

Feature

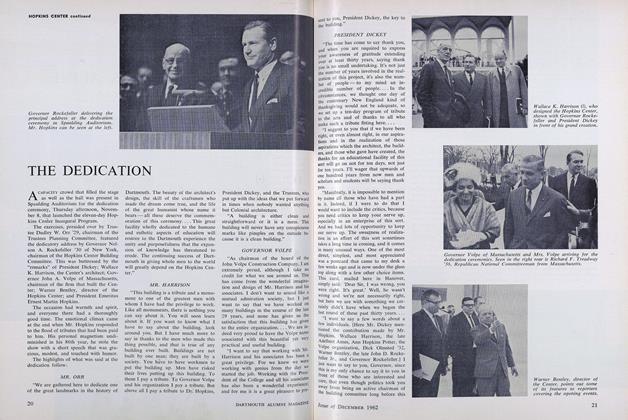

FeatureTHE DEDICATION

DECEMBER 1962 -

Feature

FeatureThe President's Answers to Some Questions During Radio Interview

DECEMBER 1971 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2008 -

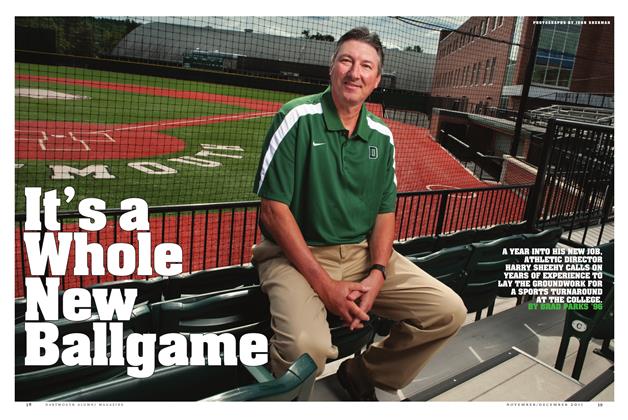

Cover Story

Cover StoryIt’s a Whole New Ballgame

Nov/Dec 2011 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

FeatureChairman's Report THE 1955 ALUMNI FUND

December 1955 By Roger C. Wilde '21 -

Feature

FeatureThe Making of a Primary Winner

MAY 1968 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70