As the Alumni Fund turns 75, a reporter takes stock of the Dartmouth bonds.

It is said that Harvard produces lawyers, Yale produces doctors and Dartmouth produces alumni. One can hardly deny that there is some truth to this bit of folklore. Of every four living Dartmouth alumni, one volunteers to help the College in some way. Each year an army of 3,500 graduates raises money for the Alumni Fund—and each year two out of every three alumni contribute in what a Wall Street Journal reporter once called "campaigns as thoroughly organized as invasions, carried through with the maddening persistence of the Chinese water torture." The same reporter noted that, "in this yearly enterprise, few schools—and none of any sizecan boast a better track record than Dartmouth."

That was in 1966. The same can be said today. Continuance of that tradition depends on a complex set of circumstances that help define the very nature of a dynamic institution.

In 1989, its seventy-fifth anniversary year, the Dartmouth Alumni Fund people plan to raise more than $12 million. If successful, it will contribute 13 percent of the College's unrestricted income, second only to tuition. Fund Director Henry Eberhardt says this is not glamour money: "It's unrestricted, and helps pay for everything from faculty salaries to cutting the grass." Not surprisingly, these everyday necessities take a big bite out of Dartmouth's current $135 million budget. Perhaps more important than the dollar amount is the lack of strings attached. The Journal of Higher Education contends that such voluntary support is becoming the only real source of discretionary money for colleges and universities and often "provides the margin of excellence, the element of vitality, that separates one institution from another."

Ever since 1854, when an association of alumni was first formed, the College has looked to its graduates for this vitality. And they have responded with a generosity and loyalty that has become legendary—if mystifying to social analysts. Historian Ralph Nading Hill says he can describe "the mechanism of Dartmouth's vital alumni movement" but not its mysteries.

Why are Dartmouth's sons and daughters so loyal? At a time of great ferment on and off campus, what will keep the bonds intact? The answer may lie in some factors, metaphysical and otherwise, that compose the legendary Dartmouth spirit.

1. Giving Tradition

Two remarkable traits help define the loyalty of Dartmouth alumni: a long history of giving, and the knowledge that most alumni have of that history. It says something about the College that the story of the Alumni Fund itself is not relegated to obscure archives. Even many students know that, after the great Dartmouth Hall fire of 1904, Melvin Adams of the class of 1871 incited Boston alumni to action with what might still be the most effective fundraising solicitation in the history of Dartmouth. "This is not an invitation, it is a summons!" his letter exclaimed.

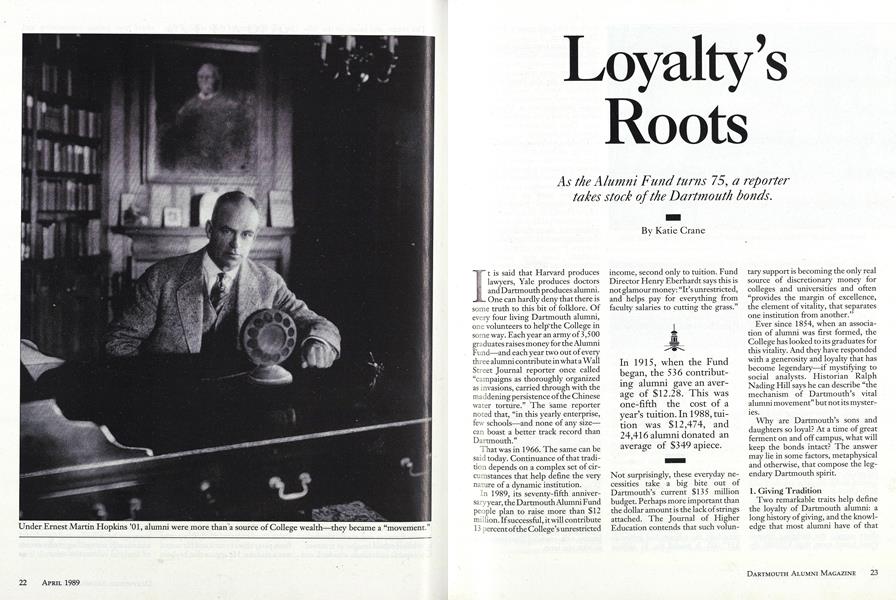

If this one event can be said to be the catalyst for rallying the alumni body, one man, Ernest Martin Hopkins, can be said to have inspired them and championed the role of Dartmouth's graduates. While working for President William Jewett Tucker, Hopkins founded the Secretaries Association, the first in a series of organizational moves that eventually led to the creation of the Alumni Council in 1913. In 1914, with Hopkins serving as its first president, the council established the Alumni Fund. Hopkins saw the Fund as an alternative to exclusive reliance on bequests or capital campaigns, preferring instead a "living endowment of limitless possibilities."

In 1916, with money in woefully short supply, the fledgling Alumni Fund raised more than $10,000. By 1918, the Fund not only covered the College's deficit of $50,000 but also raised an additional $16,000. During the 1919-20 academic year, President Hopkins made 45 appearances at alumni clubs around the country, extolling the virtues of Dartmouth's liberal education but never once requesting money. "Good Lord," asked one of his envious colleagues. "How dp you get away with that?"

Get away with that he did. By 1929 the Fund had raised $129,000 and participation had jumped to 71 percent. By 1945, Hopkins' final year as president, the amount had grown to $337,000. It passed the $1 million mark in 1961 and grew to $10 million 23 years later.

There have been times in historythe Depression, World War II, the Vietnam era—when the dollars leveled off or participation waned. But after each dip the Fund continued climbing, much to the envy of other colleges and universities. For several years participation in Dartmouth's Alumni Fund even exceeded 70 percent. These days, almost two-thirds of alumni still contribute.

This long tradition, well understood even by students at Dartmouth College, contributes a sense of obligation to the graduates who have gone on before. Whenever alumni threaten to stop giving—and this is one of those times when many are making such threats—Alumni Fund Director Henry Eberhardt '61 says he responds: "Your tuition paid for one-half of your educational costs; the alumni subsdize the other half. They didn't abandon you. Please don't abandon today's students." Each year Dartmouth's volunteers and staff encourage donors to be part of this "historic continuum."

Other schools would love to have such a tradition, according to Mona wheatley, director of Middlebury's annual fund. She knows one Dartmouth graduate from the 70s who remembers being groomed to be an alumnus from the day he set foot on the Hanover Plain. In a freshmen orientation meeting he was told that part of his bond to Dartmouth was to give something back to the school after he graduated.

Orton Hicks Sr. '21 fostered that attitude when he returned to Dartmouth in 1958 as vice president of alumni affairs and development. Hicks claims his staff had a hard time convincing him to remove someone's name from the mailing list. What if someone went to Dartmouth for only a year? Hicks would respond, "If he's been here a year, by God he owes us!" What if he'd just been here a month ? "Well," Hicks concedes, "maybe we could let him off. But we would call the college from which he graduated to make sure he was giving there." Today, the Alumni Fund solicits any person who attended Dartmouth for at least one term.

2. Sense of Ownership

In 1876, the New York Association of Dartmouth Alumni actually brought Dartmouth's president before a quasijudicial trial, complete with prosecutors, defense attorneys, and a court stenographer. During the trial, which received national publicity, President Samuel Bartlett defended himself against charges of tyrannical behavior and mismanagement. The New York alumni drew up the charges and acted as prosecutors. Bizarre as the event was (Bardett survived the trial and held on to the presidency for another decade), it was a dramatic expression of rising alumni power.

That power became concrete in 1891, when they won unprecedented representation on the Board of Trustees, filling half the seats. Bartlett's successor, William jewett Tucker, considered the political gain a quid pro quo for contributions. "Alumni government means alumni support," he said. "Representation calls for taxation as logically as taxation for representation."

The following year, the trustees agreed to allow alumni control over athletics in return for donations of athletic facilities. The result was a remodeled gym and a seven-acre athletic field with all the trappings. And alumni dominated the newly formed Athletic Council.

That sense of proprietorship continues to this day: witness the number of letters to the editor to this magazine, which exceeds that of any other alumni publication in the country. The degree of involvement sometimes rubs administrators the wrong way. President David McLaughlin '54 asserted that many alums felt their degrees were the equivalent of an institutional stock certificate. But without that share ,in the College, many officials say, the degree of giving would not be there.

3. Spirit

Joseph Bolster, who has directed Princeton's alumni giving for more than 20 years, says loyalty is related to how undergraduates at schools like Princeton and Dartmouth react to the education and overall experience at their institution. But Peter Buttenheim, director of annual giving at Williams, thinks it is more than that. He believes that the Dartmouth experience transcends the academic and athletic programs. Buttenheim, who never attended Dartmouth, nonetheless describes the experience as a depth of feeling, friendships that grow broader and deeper—a bonding-that results in a "disease one catches in Hanover while an undergraduate."

The beneficent germs are spread among arriving freshmen with amazing speed. Director of Principal Gifts Lucretia Martin '51A remembers a survey in the early 1970s asking alumni to name the three things most important to them when they were at Dartmouth. Very often, she says, they listed the freshmen trip. Perhaps it is the green eggs and ham served that final morning at the Moosilauke Ravine Lodge. With such strange fare added to a generous dose of the "Salty Dog Rag" and Doc Benton's ghost story the night before, somehow a group of impressionable teenagers begin to exhibit that intangible phenomenon that they call the Dartmouth Spirit.

Those interviewed believe Dartmouth traditions are a big source of this infectious spirit. If history repeats itself, by the time the class of 1993 builds the bonfire for the annual Dartmouth Night this October, many will have fallen victim to the disease that Henry Eberhardt says will stay with them until they die (when many families will carry on the tradition through memorial giving). Although alumni gripe that the traditions have changed substantially, enough spirit remains for Nicole Waldbaum '89 to tell the New York Times last October, "This may be the only campus in the country where most students wear sweatshirts bearing the name of their own college."

4. Sense of Place

To President Emeritus John Sloan Dickey it was "place loyalty" that accounted for Dartmouth's generous alumni. Gil Tanis '38 remembers Dickey telling alumni around the country that "we're part of the life and the stuff of this place." Virtually everyone agrees that a small college community seems to evoke a strong loyalty. Some attribute it to the rural factor, remembering their Dartmouth as off the beaten track, in the wilds of New Hampshire.

Mark Waterhouse '68 remembers even in his day thinking of Hanover as a "walled city." Certainly that was true for Orton Hicks Sr., who entered Dartmouth in 1917 only three years after the establishment of the Alumni Fund. Hicks remembers his Dartmouth as an "isolated, backwoods college" where not more than six students had automobiles. "We spent the weekends here," he recalls, "so we learned to get along with one another. We formed firm friendships, we were family."

5. Glass Identity

Arthur Hills '41 remembers another message being hammered home: class first, Dartmouth second. Class loyalty did not start with the Alumni Fund, but the Fund reinforced the concept. Dartmouth was probably the first college to organize its annual fund along class lines. Today, working with one of the smallest paid staffs in the Ivy League and the largest network of volunteers, the Alumni Fund sends tens of thousands of letters, makes thousands of phone calls and hundreds of personal appeals to the almost 44,000 living alumni—plus parents, widows, and friends of the College. Each class is led by a head agent who enlists the services of assistants who coordinate segments of a class campaign—leadership gifts, corporate matching gifts, memorial gifts and telethons. Then there is the large group of class agents who make thousands of individual contacts with classmates.

Many agents are motivated by a 50-year-old tradition of their own, the Green Derby, a competition among classes to bring in the most money and participation. Classes from the same era are clustered together to compete against each other. Classmates are usually motivated by a personal solicitation from a volunteer—a phone call, a little arm-twisting on the golf course, a personal letter. Mark Alperin '80 says he has no trouble convincing his classmates to give, if he can find them. But they are scattered around the world and are often hard to pin down. "Once I get them on the phone," he says, "the hard part's over." Alperin and his cohead agent, Meg LePage '80, personally make between 50 and 100 phone calls to classmates each year in addition to their other Fund responsibilities.

Intensive class organization is the secret weapon of the Alumni Fund, according to Henry Eberhardt. It clearly helped the class of'38 garner a record-breaking $1,070,138 last year. "We didn't work at raising money," Head Agent Gil Tanis insists. "We worked at being a good class." The class of '53 attributes its successful giving record to naming every other classmate a class agent. And the class of '88 had 220 seniors volunteer to be agents last spring, demonstrating the best organization Eberhardt says he has ever seen.

In their pursuit of fellow classmates, agents look for a few Eleazar Wheelock Fellows (those who give $25,000 or more), Associates (those who give $1,000 or more), and thousands of donors who give lesser amounts. Those loyal Dartmouth regulars, the EYSGs (every year since graduation) receive special recognition each year and a pewter bowl after giving for 60 years. The LYBUNTs and SYBUNTs (those who gave last year but not this or some year but not this) get special prodding and the old SALTs (same as last time) get some gentle encouragement to increase their gift.

6. Research

Technology has proven to be a boon to fundraising, enabling Dartmouth to segment its mailings and keep in constant touch with alumni. Even before the days of computers, however, Dartmouth had a reputation for keeping exhaustive records. "So sure as your sins shall find you out," goes an old saying, "so will Dartmouth College." Eberhardt proudly admits `this is very nearly true. There are few "lost" alumni because their classmates, not the computers, find them.

No matter how good a job he and his staffers do, however, they cannot control the external factors—the changes that alienate donors. Social and economic diversity is increasing among students and, therefore, alumni. There is talk of Dartmouth as a university and a move to lure creative loners. The feeling of Hanover as a walled city is diminishing as students routinely live off campus and study abroad. And, there is controversy.

Cliff Jordan '45 quickly dismisses controversy, which he says "goes with the territory," as a serious threat. As former director of Dartmouth's Alumni Fund, now retired, he recalls, "Every year some event on campus could give a disgruntled alumnus an excuse not to contribute." In 1933, he says, President Hopkins "saw red" because some would not contribute to the Alumni Fund until the College made "provisions for the kind of football team they wanted." Jordan remembers the furor in the 1950s when the Chicago Tribune accused Dartmouth of harboring communists on campus. And the threats in the early 1960s of withholding money because the College instituted the ABC Pro- gram for underprivileged minority youths. And the bitter arguments over abolishing ROTC. And the Vietnam War protests. These came long before today's disagreements over the Indian symbol, fraternity rush and the Re- view. And still the Alumni Fund has continued to increase.

But the experts worry about taking the alumni for granted, pointing out the impact on the Fund of the shanty incident in 1986. After members of the Dartmouth Review were punished for destroying anti-apartheid structures on the Green, dollars went down (by almost $357,000 from the previous year) while the number of letters written to the Fund by alumni went up five-fold. And yet, donors seem remarkably understanding: the Fund increased by a million dollars and broke records in the tax-reform year of 1987.

Still, Henry Eberhardt is concerned this year. As of the end of February, the dollars were where he had projected them to be (some $6.8 million), and participation was about what it had been last year, but the letters"lots of them," he says—are up.

Princeton's Joseph Bolster offers the consolation that his university's alumni fund weathered a rough period a few years ago when a group called Concerned Alumni For Princeton published the periodical Prospect, which he described as a "challenging presence" for several years. Williams' Buttenheim says he doubts Dartmouth will take any long-term hits. He believes alumni will come around because students of liberal learning are "taught not to abandon the symphony orchestra just because we don't like the third violinist."

But even Cliff Jordan, an optimist by long experience, has some concerns: "With the changes—particularly some of the things President Freedman is talking about—some of us wonder whether Dartmouth can continue the level of alumni giving and percent of participation ten or 20 years from now."

Some of this year's class agents share Jordan's concern. In an article about donor behavior, thejournal of Higher Education suggests that an institution's "public profile" has a vital impact on donor behavior. Not surprisingly, agents are worried about Dartmouth's profile, because they say it deflects attention from the good things that are happening on campus. Jack Cramer, the '57 head agent, lost a key member of his management team and three class agents because, as he puts it, "the pot is boiling." Both Mark Waterhouse '68 and Mark Alperin '80 lost agents over delayed rush. Gil Tanis '38 admits that some of his classmates are also concerned about various controversies on campus, but he reports that the class numbers look good. "People I count on are giving," he says. Arthur Hills' class of 1941 is divided-"more divided than most," he thinks. Some classmates are voting with their dollars, reducing their contributions to token amounts, diverting their money to the Dartmouth Review defense fund, even removing the College from their wills.

And yet, Hills says, one of the most ardent dissenters continues to contribute to the Fund even as he voices his opinion with President Freedman and others. That is the way it should work, according to Eberhardt. "We're not asking alumni to give money in order to cast their vote," he says. "We're asking for money in order to support Dartmouth's 4,300 undergraduates."

But, as President Tucker said at the beginning of the century, one reason alumni support Dartmouth is that they have a vote. All but one of the current trustees are alumni, and half are nominated by a large Alumni Council Dartmouth's graduates continue to have a say (albeit a diminished one) in athletics, administration, even in some academic matters. The formation of the dissident Hopkins Institute, alumni support of the Dartmouth Review, and increasingly regular challenges to the Alumni Council's nominations for trustees may be signs that a significant number of alumni are not happy with this degree of power.

The. loyalty factors are still there: the giving habits, the Dartmouth Spirit, the sense of place, fundraising research. Will those factors survive the current controversies, as they have prospered through the many difficult eras in the past? The answer may lie in a single, all-important factor: whether Dartmouth can best Yale's doctors and Harvard's lawyers by continuing to produce alumni.

Modern College fundraising arose out of the flames of Dartmouth Hall.

Even before Hopkins built a formal alumni structure, rrads in the 1890s took on the construction of facilities such as this seven-acre athletic field (left.)

Before the president receives the giant checks, classes mobilize the largest group of volunteers in the Ivies.

While the classes hold their own telethons, calls by students at an annual on-campus event have helped the Alumni Fund break records.

Fund Director Henry Eberhardt says the letters are way up this year.

Generals of the Alumni Fund army, the head agents are led by Al Collins '53.

Writer Katie Crane lives in White River Junction, Vermont.

In 1915, when the Fund began, the 536 contributing alumni gave an average of $12.28. This was one-fifth the cost of a year's tuition. In 1988, tuition was $12,474, and 24,416 alumni donated an average of $349 apiece.

Dartmouth's most loyal alumni may be Arthur H. Lord '10, Roger Evans '16 and Richard Parkhurst '16. Through 1988 each had been contributing for 71 years for a total of 213 years.

In 1978, the class of '53 became the first to raise a million dollars in a single year. Thirteen other classes have followed suit.

Most experts agree that Dartmouth's Alumni Fund regularly gets the highest participation of any large school. Williams wins the mid-sized category, and tiny Centre College in Kentucky leads the small schools.

At 75, the Dartmouth Alumni Fund is the fourth oldest in the Ivy League. (Yale's is the oldest.)

The 1989 student telethon set a new record. Students solicited $403,204. The Alumni Fund gave a t-shirt to each student who garnered four or more pledges.

In the years immediately following coeducation, a higher percentage of women gave to the Fund than men did, but the average gift by alumnae was smaller. Alumni Fund Director Henry Eberhardt says giving behavior is now about the same for both sexes.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

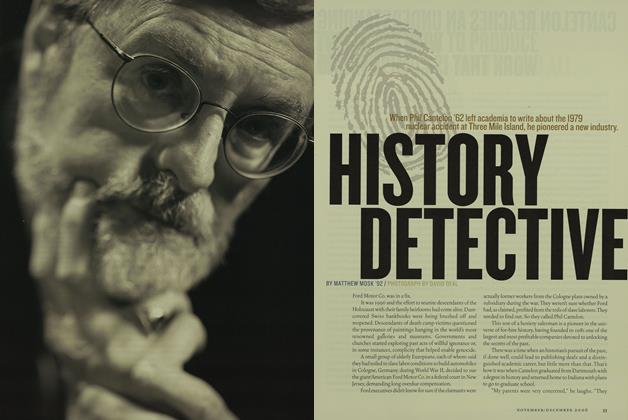

FeatureSix Questions for the Candidates

April 1989 -

Feature

FeatureIT'S GOOD

April 1989 By Dinesh D'Souza '83 -

Feature

FeatureIT'S BAD

April 1989 By Edward C. Ingraham '43 -

Feature

FeatureHis Honor, Jock McKernan

April 1989 By Thomas Lynn Avery '70 -

Feature

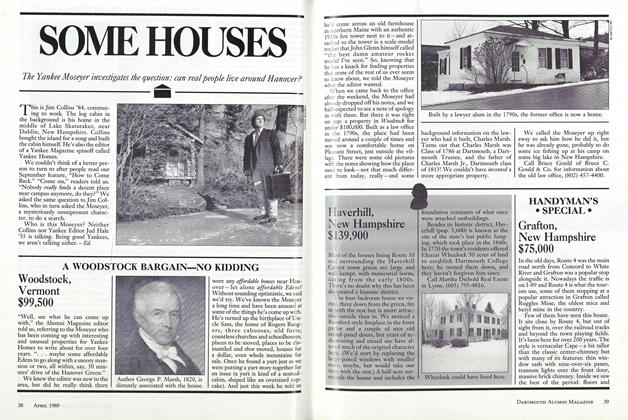

FeatureA WOODSTOCK BARGAIN—NO KIDDING

April 1989 -

Feature

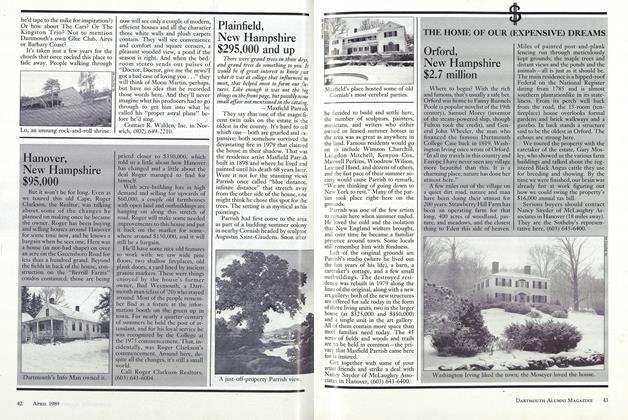

FeaturePlainfield, New Hampshire $295,000 and up

April 1989