By Robert Kenneth Faulkner'56. Princeton University Press, 1968. 307pp. $10.

John Marshall became Chief Justice of the Supreme Court after John Jay, the first Chief Justice, had declined reappointment by President Adams, because Jay was convinced that the judiciary system established by the new constitution was "so defective" it could never attain weight and dignity nor acquire public confidence and respect. Justice Holmes has said that Marshall's opportunity was the greatest that ever fell to a judge, and the author of this book corrects the record by adding, "The chance was grasped. In what was yet a new nation, with newer institutions, with deep divisions among the departments of government, Marshall and his Court were forced to contrive, and even to record authoritative solutions to problems touching the very basis of the American order."

It is Marshall's blend of knowledge, derived from Locke and Blackstone, with practical and statesmanlike judgment, which the author calls "Marshall's Constitutional understanding," that the book portrays.

The author has achieved his aim to offer a systematic exposition and analysis of Marshall's political ideas, with a lucidity that the great Chief Justice might have approved, by thorough examination of some of Marshall's leading constitutional opinions and his public writings and private correspondence. The author contends that with all its concern for social unity, public order, and national power, the end of Marshall's jurisprudence was the security and comfort of the individual and, hence, was fundamentally humanitarian.

The discussion of Marshall's success in establishing the doctrine of judicial review is particularly illuminating. The author shows that the rhetorical skill of Marshall's constitutional opinions, beginning with Marbury v. Madison lay in his "prudently cautious inculcation in memorable phrases of only principles necessary for public belief," without running the risk of preaching democracy's limitations in the ears of Jefferson and Jackson, which might have resulted in the overthrow of the Court.

The tone throughout the text is judicious and dispassionate, but in an appendix which considers Justice Holmes' critique of Marshall, the author lets himself go in an eloquent attack on Holmes' theories of social Darwinism which will delight readers who prefer Marshall's principles of republican liberalism.

Senior partner in Davies, Hardy, Loeb, Austin & Ives, 2 Broadway, New York, Mr.Loeb will become a resident of Norwich,Vt., after his retirement in June 1969.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureJames Marsh, Dartmouth, and American Transcendentalism

March 1969 By Douglas M. Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeatureFaculty Votes Reduced Status for ROTC

March 1969 -

Feature

FeatureReaching Out from Hanover

March 1969 By Ron Talley '69 -

Feature

FeatureCOED WEEK: A Taste of the Future?

March 1969 -

Article

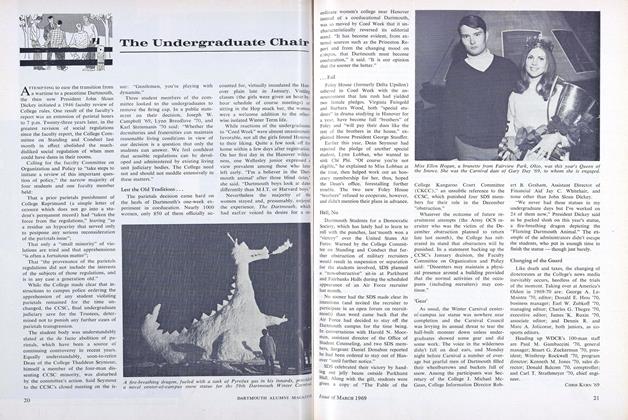

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

March 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

March 1969 By WALTER S. YUSEN, WILLIAM C. VAN LAW JR.

ROBERT L. LOEB '21

Books

-

Books

Books"Chemistry of the Opium Alkaloids"

March 1933 -

Books

BooksTHE SOCIAL FUNCTIONS OF EDUCATION

May 1937 By Irving E. Bender -

Books

BooksMICROSCOPIC IDENTIFICATION OF CRYSTALS.

JULY 1972 By JOHN SLOAN DICKEY JR. '63 -

Books

BooksDEMOTIC GREEK: INSTRUCTION BY THE ORALIA URAL METHOD.

JANUARY 1973 By PAUL W. WALLACE -

Books

BooksTHE WEDDING BOOK.

NOVEMBER 1964 By PRISCILLA AND ALAN ROZYCKI '61 -

Books

BooksJOBS TO TAKE YOU PLACES — HERE AND ABROAD.

MARCH 1969 By SUSAN A. LIDDICOAT