CHIEF JUSTICE OF THE UNITED STATES

IT is a great pleasure for me to be present with you today, and to join you in memorializing two significant years that have in their various ways contributed to the welfare of your College and to the Nation. In its 200 years Dartmouth College, through its thousands of graduates, has spread enlightenment to every corner of the land, and in the 150 years since the Dartmouth College Case the place of Daniel Webster in American history has not only become more secure but has ranked him as perhaps the greatest advocate in the long history of the Supreme Court.

I have been interested to discover from the historical record that this is the second time in this century that a Chief Justice of the United States has, at the invitation of Dartmouth College, taken part in a ceremony honoring the College's most famous alumnus, Daniel Webster. In 1901, one of my distinguished predecessors, Melville W. Fuller, journeyed to Hanover to attend the celebration of the centennial of Webster's graduation fron? Dartmouth.

He spoke at the closing banquet — an affair which, again I find from the record began at six-thirty in the evening, with the Chief Justice reached in the order of speakers at one o'clock in the morning. Today, our Court would almost certainly hold this to be in conflict with the Eighth Amendment's proscription of cruel and unusual punishments —if not for the Chief Justice, at least for his audience. I, thankfully, face you under considerably less formidable circumstances.

There were, as Chief Justice Fuller remarked on that earlier occasion, some "special considerations" which moved him to accept the College's invitation. Both of his grandfathers had been students at Dartmouth during Webster's undergraduate days. His Fuller grandfather had, indeed, been in Webster's class, and a close youthful friendship was formed which continued throughout their adult years. It was largely for this reason that Chief Justice Fuller himself had, while an undergraduate at Harvard nearly fifty years before, made the trip from Cambridge to Marshfield to pay his respects at Webster's funeral.

But as Chief Justice Fuller went on to of his presence at Dartmouth in 1901, "there was another and weightier cause that impelled me, a sense of duty to testify by my personal attendance to the tie that binds the memory of this great minister of justice to the Court, in aid of whose labors some of the most splendid manifestations of his intellectual power were exhibited." It is with that same sense of respect for a great advocate at the bar of our Court that I join in your commemoration today.

To call the roll of the great cases in which Webster appeared, and in which he prevailed, is to describe the process by which the Federal Constitution became a vital force in American life. They include such foundation stones of modern constitutional law as McCulloch v. Maryland, which recognized the implied powers of the new government and established their supremacy, and Gibbons v. Ogden, which created the conditions for the subsequent use by the Congress of the Commerce Clause to achieve a host of important public purposes. We decide cases today within the framework of the great concepts of self-government born and shaped in these pioneering decisions.

As to the Dartmouth College Case itself, I am in the midst at the moment of many representatives of Webster's winning client, and clients are notoriously less interested in the grounds of decision than in the result. It was, after all, a small college, confronted by a very formidable state government; and, in the David and Goliath context, it is the failure of logic to command the result that brings the happy ending.

Judge Henry Friendly, in his Oliver Wendell Holmes Devise Lecture at Dartmouth last year, has noted that "one of the great contributions of the [Case] was the impetus it gave to voluntary associations as a factor in American life." The importance of that factor in the shaping of our society is surely substantial, but Judge Friendly also noted that the question of when a private educational association takes on the characteristics of a public institution for certain purposes is perhaps a more complex and difficult one than Chief Justice Marshall assumed it to be in 1819. At least that would appear to be true today, as Judge Friendly illuminates at length in his interesting exploration of the problem.

By emphasizing Dartmouth's private and voluntary aspects, Webster won the lawsuit in question.

It is interesting that, not many years later and in another lawsuit, he sought to break Stephen Girard's will because the school it endowed was directed to exclude all manifestations of organized religion, a circumstance which, so Webster argued, conflicted with public policy to such a degree as to warrant nullification by governmental authority of an owner's desires for the disposition and utilization of private property. Webster's clients did not succeed on that occasion; and, in view of the later history of the Girard will, I do not pursue the matter other than to observe that Webster might be the first to agree that the immunity of seemingly private activity from public control is not a static concept.

There has long been, as we all know, a respectable body of opinion extant that the Dartmouth College Case came out the right way but for the wrong reasons. In putting this viewpoint forward with great vigor at the New Hampshire celebration of the John Marshall Centennial, Professor Jeremiah Smith of the Harvard Law School, a son of one of the lawyers for the College, felt it appropriate under the circumstances to add what are, to me at any rate, these comforting words: "That Marshall made occasional mistakes may be safely admitted without seriously detracting from his judicial reputation." And an authentic voice of the College in the current ALUMNI MAGAZINE has usefully reminded us that what the Supreme Court undertook to save by its decision was the College, and not the world.

It was worth saving and has since thoroughly justified the emotional character given to it by Webster when he said, "It is a small college, but there are those who love it." By any measuring stick, it was a memorable case. In the first place, it was Webster's first important case in the Supreme Court of the United States. It preserved the life and independent character of one of the fine old private colleges of America, which were the progenitors of our system of higher education. In doing so, it also guaranteed the self-determination of all such small colleges and gave a sanctity to contracts generally which has greatly affected the economic as well as the academic life of the Nation.

IF, as I believe with Chief Justice Fuller when he said in that earlier ceremony nearly seventy years ago, "it is impossible to overestimate the support that the court derives from the bar," how is it possible to exaggerate the debt which John Marshall must have owed to Webster's powerful formulations of constitutional principle, or to understate his contributions to the benevolent purposes which the Federal Republic has been able to achieve because of them? If any proof were needed, surely Webster's career as a great advocate in adversary litigation demonstrates that private practitioners of large vision frequently advance great public ends in the course of their daily work.

Those ends are not invariably concerned with commercial enterprises and property interests. I have also been interested to discover that Webster's representation before the Supreme Court was not always confined to such clients as the Bank of the United States and a New Jersey operator of steamboats. In 1820, only a year after his superior legal talents bore fruit in the Dartmouth College Case, Webster was appointed by the Court to serve without compensation as counsel for fifty unfortunate men who had been convicted of piracy in the federal courts and sentenced to death.

The prospects of success on appeal were bleak and, in the end, even Webster's skill proved unavailing for his destitute and unpopular clients. But his unreserved and energetic response to this summons to appear in an unappealing and forlorn cause was a building block in a great edifice, and one which looms the larger on the legal horizon of today because of his example. Currently there are thousands of American lawyers who are called upon each year to follow in his footsteps, and who do so generously and without complaint, despite the inevitable disruptions of their professional practice and the misunderstanding with which laymen view at least some of their efforts.

Over the years the lawyers who have responded in this manner have enabled the courts to assure that no person seriously involved with the criminal law must stand at the bar of justice alone, no matter how humble he may be in the social and economic scale or how repellent his conduct may seem to have been. This tradition has not only added a civilized aspect to our society which is gratifying to those who live in it, but it also presents one of the more appealing faces of that society to the world at large. Moreover, the mobilization of professional talents and experience on such a wide scale, and their direction to what was for long a neglected area of the law, have resulted in many improvements, legislatively and judicially, in criminal law and procedure. We face the staggering problems of the present the better because of this past. I am especially happy on this occasion to note in that past the presence and example of Daniel Webster.

The goal of equal justice under law is however, an ever receding one. Long steps towards its realization only reveal further steps to be taken. The progreSs made in the provision of counsel in the trial and appellate phases of the criminal law has been notable, but much remain; to be done even in that limited area Congress, with the passage of the Criminal Justice Act of 1965, recognize the equity of a wider sharing of the finan. cial burdens necessarily entailed in the representation of indigents by private lawyers in the federal courts. In many cases that provision is far from fully compensatory.

Lawyers do not expect to be spared all the personal burdens of a professional tradition of public service, but they can rightly insist that there be an allocation of public resources commensurate with the scale of the problem. A lawyer who gives of his time and energy without adequate compensation is certainly entitled to claim that there be adequate facilities to guarantee speedy trial. And when and if the prison doors clang behind the 20-year-old defendant he has made his sacrifices for, he can demand that the correctional system be given a fighting chance to effect the rehabilitation which will not require another appointed lawyer a few years hence. That lawyer also, I suggest, has legitimate credentials to assert that the country at large get on with the job of trying to prevent more 20-year-old offenders from springing up to take the place of his late client in the prisoners' dock.

THERE is another aspect of Webster's ' legal career which has a high degree of contemporary relevance. This was his persisting interest in the continuous improvement of the machinery by which justice is administered. This interest, already evident in his early years at the bar, was happily given opportunity for expression upon his first accession to public office. Throughout his service in the lower house of Congress four years as a representative from New Hampshire and four from Massachusetts - he was on the House Judiciary Committee, serving as its chairman during the latter period.

Webster's maximum efforts in this capacity were pointed toward the rationalization of the structure of the federal judicial system so that it might function more efficiently. He labored at legislation to deal with the growing needs of the western states for more federal courts, and with the heavy burdens, and consequent backlogs, of the Supreme Court Although close to success in this effort on at least two occasions, he was eventually frustrated by political partisanship, liberally compounded by dislike in some quarters for certain of the Court's decisions and some of its members.

Webster, as a lawyer and legislator, never made the mistake of projecting disagreement as to particular decisions into the area of institutional design. He wanted the Court always to have the jurisdiction, structure, and resources best enabling it to function fairly and efficiently, and he vigorously opposed the resolution of those questions by reference to the nature of its current rulings. On the floor of the House he once had occasion to respond to a fellow member who opposed his judicial reform bill because of an allegedly misconceived ruling by the Supreme Court. Webster's words were:

"It would be unworthy, indeed, of the magnitude of this occasion, to bend our course a hair's breadth on the one side or the other, either to favor or to oppose what we might like, or dislike, in regard to particular questions. Surely we are not fit for this great work, if motives of that sort can possibly come near us."

Webster's years on the House Judiciary Committee also included pioneering work by him in the drafting of legislation implementing the national bankruptcy power but, as in the case of his proposals for structural reform, others were to reap at a later date the benefits of his efforts. As early as 1816, he proposed to confer upon the federal courts what we lawyers call "federal question" jurisdiction, that is to say, claims arising under the Constitution, and the laws and treaties of the United States. This did not commend itself to his Congressional colleagues, but 60 years later another Congress enacted this provision with virtually no dissent in the swelling stream of national sentiment which characterized post-Civil War America. Today that jurisdiction is widely regarded as the critical justification for the existence of the lower federal courts.

In another area of law reform, Webster had more immediately visible success. Upon the urging of Justice Story, he undertook the preparation of a comprehensive Federal Criminal Code, with the purpose of bringing some precision and certainty into an area which was characterized by a vast amount of confusion during the early years of the federal courts. Webster had the satisfaction of seeing that Code become law in 1825 before he left the House Judiciary Committee upon his election to the Senate.

I referred earlier to the present relevance of this aspect of Webster's life in the law. It is also especially appropriate for us to take note of it in this place — the new complex of buildings on Lafayette Square devoted to the interests and improvement of the federal judicial system. The handsome new building we are now in is indicative of the scale of commitment required to meet the physical needs of two units of that system which exercise a nation-wide jurisdiction over important subjects. The equally handsome but older adjoining buildings house old and new activities of critical importance to the future of all our federal courts. The Administrative Office of the United States Courts, under Mr. Friesen, has for some years been in charge of budgetary, housekeeping, and statistical functions, although its responsibilities inevitably embrace a broader concern with judicial administration.

Congress has recently and wisely recognized, however, that there is a need for continuous planning, research, and education in respect of judicial administration. The restored Dolly Madison House was dedicated only last November to the use of the new Federal Judicial Center which Congress has brought into being to perform these tasks. The promise of this new entity is the more likely to be realized because of the happy circumstance of the willingness and availability of my friend and colleague, Mr. Justice Clark, to serve as its first Director. The litigation explosion, which threatens the engulfment of many of our courts, state and federal, is an urgent object of concern, and the quality of justice in this country will be closely affected by what goes on in these immediate environs. Since that quality was so much a concern of Webster's in his own time, it is particularly fitting that this meeting be held in this nerve center of the federal judicial system.

THERE is a third aspect of Webster's career which no one in my position can fail to appreciate. In both the private and the public phases of that career, he was tireless in his efforts to sustain and protect the independence and the integrity of the federal courts, and their authority to give meaning to the language of the Constitution. His was a lifelong vision of the Federal Union as the essential instrument of our national strength and well-being. Although a New England Federalist in his early political affiliation, he would have no part of the Hartford Convention, where Yankees flirted with the idea of secession. The idea was equally abominable to him when it found expression in the South, and the last great cause of his life was the damping down, by means of the Compromise of 1850, of the threat of the breakup of the Union.

What was clear to him throughout, however, was that the preservation of the federal government, and of the Constitution creating it, was dependent upon respect for the authority of the Supreme Court and the inferior federal courts and respect which did not ebb and flow with tides of feeling towards particular decisions. As a member of the House Judiciary Committee, Webster was periodically confronted with legislative proposals generated by current dissatisfactions with the Supreme Court. These proposals included abolition of the Court's appellate jurisdiction in state cases, transfer of that jurisdiction to the Senate, requirement of a two-thirds vote, and so on.

Although Webster lost his full share of cases in the Supreme Court, and had his moods of unhappiness about its functioning, his reaction to this kind of retaliation was stern and unswerving opposition. That opposition was a powerful factor in the failure of those proposals, thereby founding a tradition of such failure which, happily, has largely prevailed ever since.

When South Carolina first seriously asserted the power of an individual state to nullify an Act of Congress, Webster's great powers of constitutional analysis provided the intellectual foundations for Andrew Jackson's more emotional response. It is one of our historical delights that these two arch political enemies joined hands in a cause which both agreed was bigger than either one of them. It was on the floor of the Senate, and in defense of a Congressional statute against state negation, that Webster took his stand. But he always described that effort as comprehending the principle that, just as a state may not nullify a federal statute, so it may not defy a Supreme Court judgment. His famous Reply to Hayne was, in his conception, as demonstrative of federal judicial authority, as of federal legislative authority, in the respective areas defined by the Constitution.

It was a conception rooted in Webster's deep conviction that, as he once put it in a House speech in support of a judiciary bill, "the maintenance of the judicial power is essential and indispensable to the very being of this government. The Constitution without it would be no constitution; the government, no government."

It was a personal article of faith which enabled him in the same speech to say of the federal judiciary and of the Supreme Court as its head: "It may have friends more able [than myself], it has none more sincere."

The passage of time has neither obscured nor undermined his claims to that attachment. Neither has the course of our subsequent history impaired his underlying premises as to the essential elements of constitutional government. A free people, then as now, require a free judiciary.

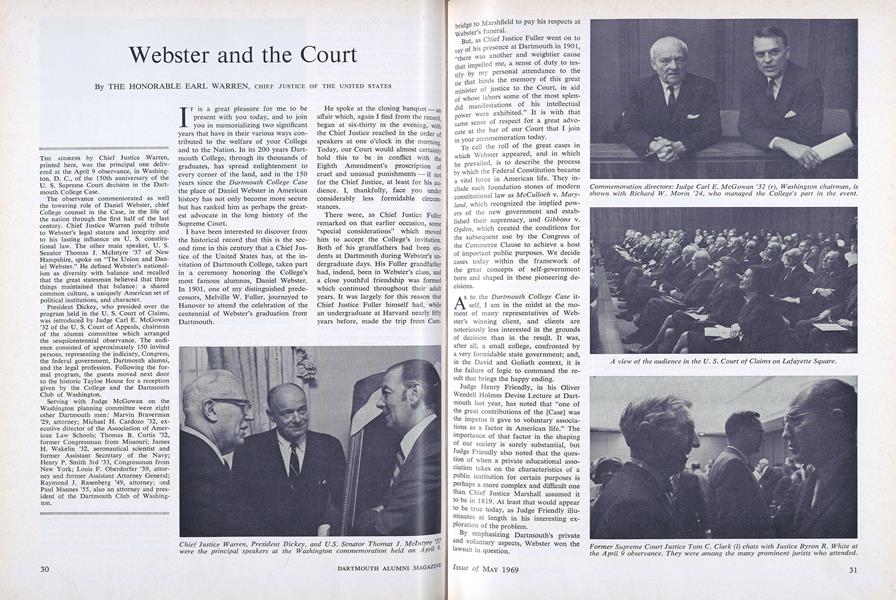

Chief Justice Warren, President Dickey, and U.S. Senator Thomas J. McIntyre '37were the principal speakers at the Washington commemoration held on April 9.

Commemoration directors: Judge Carl E. McGowan '32 (r), Washington chairman, isshown with Richard W. Morin '24, who managed the College's part in the event.

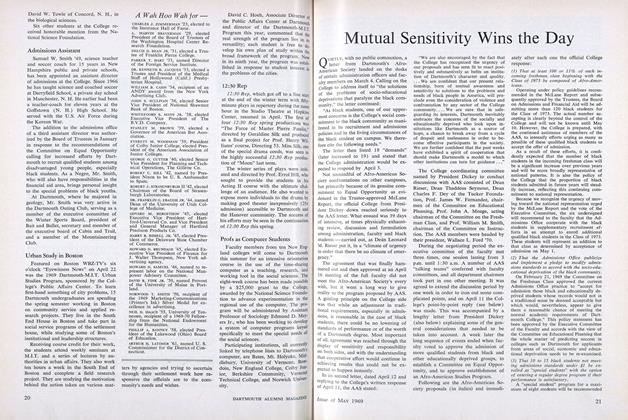

A view of the audience in the U. S. Court of Claims on Lafayette Square.

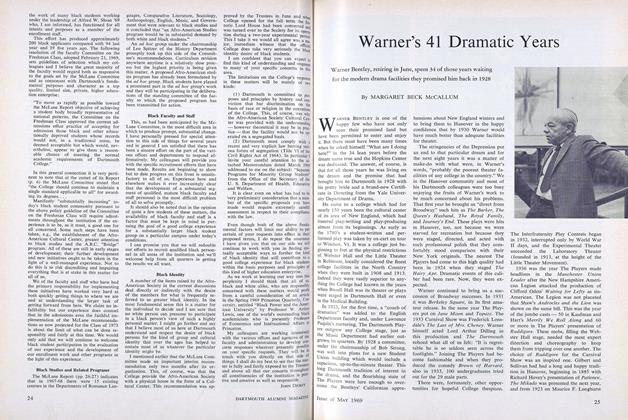

Former Supreme Court Justice Tom C. Clark (l) chats with Justice Byron R. White atthe April 9 observance. They were among the many prominent jurists who attended.

Chief Justice Warren giving address.

THE ADDRESS by Chief Justice Warren, printed here, was the principal one delivered at the April 9 observance, in Washington, D. C., of the 150th anniversary of the U. S. Supreme Court decision in the Dartmouth College Case. The observance commemorated as well the towering role of Daniel Webster, chief College counsel in the Case, in the life of the nation through the first half of the last century. Chief Justice Warren paid tribute to Webster's legal stature and integrity and to his lasting influence on U. S. constitutional law. The other main speaker, U. S. Senator Thomas J. McIntyre '37 of New Hampshire, spoke on "The Union and Daniel Webster." He defined Webster's nationalism as diversity with balance and recalled that the great statesman believed that three things maintained that balance: a shared common culture, a uniquely American set of political institutions, and character. President Dickey, who presided over the program held in the U. S. Court of Claims, was introduced by Judge Carl E. McGowan '32 of the U. S. Court of Appeals, chairman of the alumni committee which arranged the sesquicentennial observance. The audience consisted of approximately 150 invited persons, representing the judiciary, Congress, the federal government, Dartmouth alumni, and the legal profession. Following the formal program, the guests moved next door to the historic Tayloe House for a reception given by the College and the Dartmouth Club of Washington. Serving with Judge McGowan on the Washington planning committee were eight other Dartmouth men: Marvin Braverman '29, attorney; Michael H. Cardozo '32, executive director of the Association of American Law Schools; Thomas B. Curtis '32, former Congressman from Missouri; James H. Wakelin '32, aeronautical scientist and former Assistant Secretary of the Navy; Henry P. Smith 3rd '33, Congressman from New York; Louis F. Oberdorfer '39, attorney and former Assistant Attorney General; Raymond J. Rasenberg '49, attorney; and Paul Mannes '55, also an attorney and president of the Dartmouth Club of Washington.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMutual Sensitivity Wins the Day

May 1969 By JOHN DICKEY -

Feature

FeatureWarner's 41 Dramatic Years

May 1969 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Feature

FeatureMay 17 Event to Salute Eleazar's Starting Point

May 1969 -

Books

BooksERNEST HEMINGWAY: A LIFE STORY

May 1969 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

May 1969 By STANLEY H. SILVERMAN, WILLIAM S. EMERSON

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTRUSTEES SANCTION A FOURTH TERM

OCTOBER 1962 -

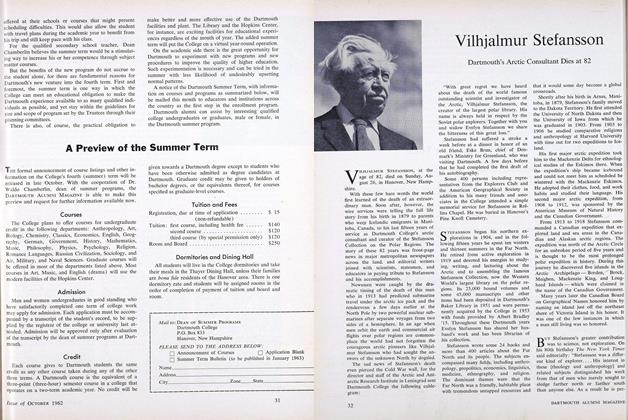

Cover Story

Cover StoryDaughters of Dartmouth

NOVEMBER 1988 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

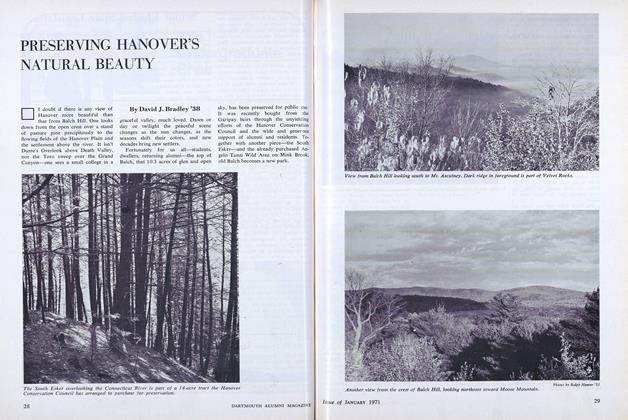

FeaturePRESERVING HANOVER'S NATURAL BEAUTY

JANUARY 1971 By David J. Bradley '38 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Dartmouth Disease

SEPTEMBER 1983 By George O'Connell -

Feature

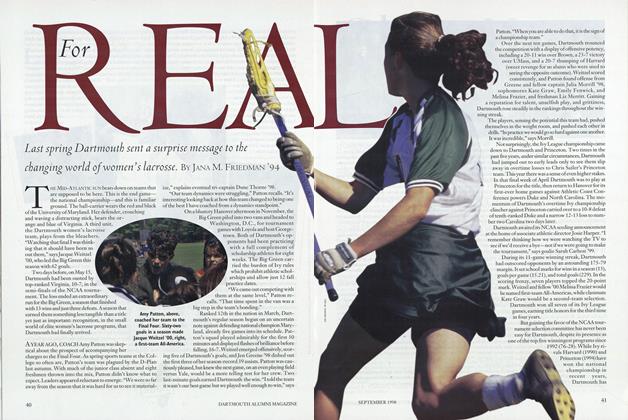

FeatureFOR REAL

SEPTEMBER 1998 By Jana M. Friedman '94 -

Feature

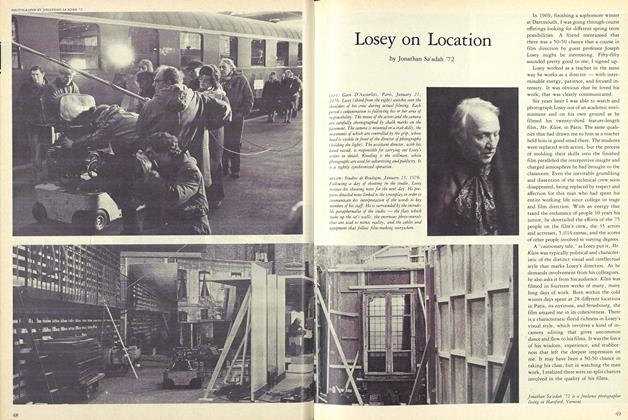

FeatureLosey on Location

November 1982 By Jonathan Sa'adah '72