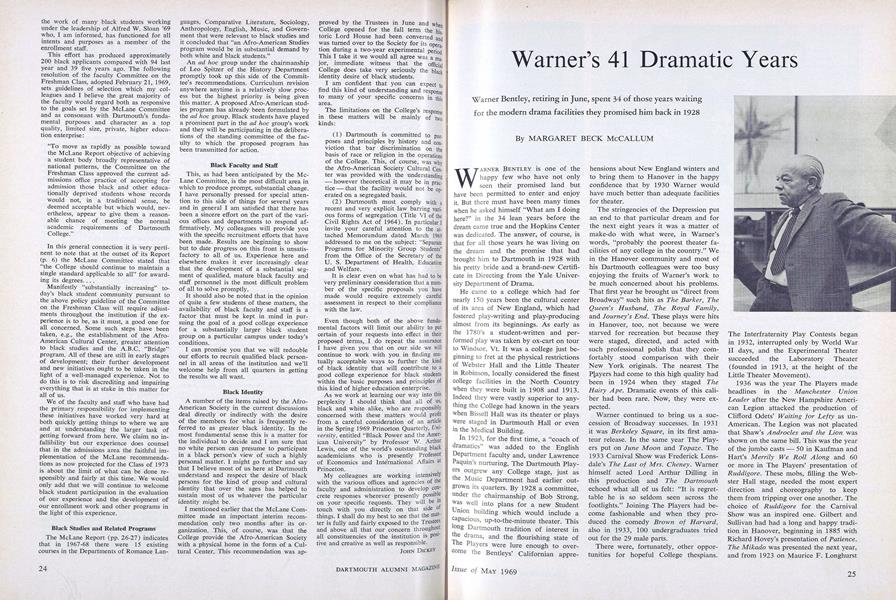

Warner Bentley, retiring in June, spent 34 of those years waiting for the modern drama facilities they promised him back in 1928

WARNER BENTLEY is one of the happy few who have not only seen their promised land but have been permitted to enter and enjoy it. But there must have been many times when he asked himself "What am I doing here?" in the 34 lean years before the dream came true and the Hopkins Center was dedicated. The answer, of course, is that for all those years he was living on the dream and the promise that had brought him to Dartmouth in 1928 with his pretty bride and a brand-new Certificate in Directing from the Yale University Department of Drama.

He came to a college which had for nearly 150 years been the cultural center of its area of New England, which had fostered play-writing and play-producing almost from its beginnings. As early as the 1780's a student-written and performed play was taken by ox-cart on tour to Windsor, Vt. It was a college just beginning to fret at the physical restrictions of Webster Hall and the Little Theater in Robinson, locally considered the finest college facilities in the North Country when they were built in 1908 and 1913. Indeed they were vastly superior to anthing the College had known in the years when Bissell Hall was its theater or plays were staged in Dartmouth Hall or even in the Medical Building.

In 1923, for the first time, a "coach of dramatics" was added to the English Department faculty and, under Lawrence Paquin's nurturing, The Dartmouth Players outgrew any College stage, just as the Music Department had earlier outgrown its quarters. By 1928 a committee, under the chairmanship of Bob Strong, was well into plans for a new Student Union building which would include a capacious, up-to-the-minute theater. This long Dartmouth tradition of interest in drama, and the flourishing state of The Players were lure enough to overcome the Bentleys' Californian apprehensions about New England winters and to bring them to Hanover in the happy confidence that by 1930 Warner would have much better than adequate facilities for theater.

The stringencies of the Depression put an end to that particular dream and for the next eight years it was a matter of make-do with what were, in Warner's words, "probably the poorest theater facilities of any college in the country." We in the Hanover community and most of his Dartmouth colleagues were too busy enjoying the fruits of Warner's work to be much concerned about his problems. That first year he brought us "direct from Broadway" such hits as The Barker, TheQueen's Husband, The Royal Family, and Journey's End. These plays were hits in Hanover, too, not because we were starved for recreation but because they were staged, directed, and acted with such professional polish that they comfortably stood comparison with their New York originals. The nearest The Players had come to this high quality had been in 1924 when they staged TheHairy Ape. Dramatic events of this caliber had been rare. Now, they were expected.

Warner continued to bring us a succession of Broadway successes. In 1931 it was Berkeley Square, in its first amateur release. In the same year The Players put on June Moon and Topaze. The 1933 Carnival Show was Frederick Lonsdale's The Last of Mrs. Cheney. Warner himself acted Lord Arthur Dilling in this production and The Dartmouth echoed what all of us felt: "It is regrettable he is so seldom seen across the footlights." Joining The Players had become fashionable and when they produced the comedy Brown of Harvard, also in 1933, 100 undergraduates tried out for the 29 male parts.

There were, fortunately, other opportunities for hopeful College thespians. The Interfraternity Play Contests began in 1932, interrupted only by World War II days, and the Experimental Theater succeeded the Laboratory Theater (founded in 1913, at the height of the Little Theater Movement).

1936 was the year The Players made headlines in the Manchester UnionLeader after the New Hampshire American Legion attacked the production of Clifford Odets' Waiting for Lefty as UnAmerican. The Legion was not placated that Shaw's Androcles and the Lion was shown on the same bill. This was the year of the jumbo casts — 50 in Kaufman and Hart's Merrily We Roll Along and 60 or more in The Players' presentation of Ruddigore. These mobs, filling the Webster Hall stage, needed the most expert direction and choreography to keep them from tripping over one another. The choice of Ruddigore for the Carnival Show was an inspired one. Gilbert and Sullivan had had a long and happy tradition in Hanover, beginning in 1885 with Richard Hovey's presentation of Patience.The Mikado was presented the next year, and from 1923 on Maurice F. Longhurst of the Music Department had annually produced one of the popular operas. Mr. Longhurst directed the Handel Society and Chorus for Ruddigore, with Henry Williams as technical supervisor, but Warner brought Otto Asherman of Boston to Hanover to train the largest cast ever seen on a local stage, playing to the largest audience. And 1936 was the year when, not counting the Interfraternity Plays, The Players presented seven full-length plays, with fifteen performances, to nearly 7000 people in the College's two theaters - Webster Hall, which seated a maximum of 1300 and had never been really intended for a theater, and the Little Theater, which held 300. Even the applauding public began to be aware of some of the difficulties under which Warner and his players worked, and as a sort of pacifier the Trustees put a fund of a thousand dollars at the disposal of The Players to make up any losses incurred, particularly by the inadequate seating capacities of the two theaters.

They did more. They made plans, announced in December 1938. A new Webster Hall had been designed by J. Fredrick Larson, the College architect. Music and theater would be brought under one roof. Its auditorium could seat as many as 2700 or, divided by curtains, as few as 850. Its intimate Little Theater would hold 420. The plans called for it to be built on the site of Bissell Hall, looking north to the old Webster Hall and it would be a cultural center for the whole Hanover area, a place for theater and concerts, for Summer Drama Festivals. Drawings of the front facade and the interior harmonized grace and elegance. The committee, headed by Sidney C. Hayward '26, was happy; so was Warner, and we were happy with them. We had reached the era when The Players were regularly offering five full-length plays a year, the Experimental Theater five "academic" or "artistic" plays, and the Interfraternity Plays 20 to 24 one-act productions, all under circumstances to drive a director to distraction. It is important to keep in mind that the difficulties and frustrations which Warner and his students lived with were never really apparent to their audiences. We knew, of course, that better facilities were desperately needed, but the lack of their, never overtly affected the quality of acting, direction, and stagecraft.

THE Players were in dress rehearsal for The Importance of Being Earnest when war was declared on November 7, 1941. The difficult decision was made that the show must go on, and so it did. for three performances. Three other plays were staged during that uncertain academic year, including Owen Davis' hit of 1906, At Yale, which was a happy choice for a half-hearted Carnival. The lovely dream of a new Webster Hall faded.

The war years saw Warner's finest effort. Putting disappointment behind him he made do magnificently with what he had. For the Naval Officers Training School in 1942-43 he mounted almost a play a month, and not easy plays, either. Maxwell Anderson's The Eve of SaintMark had a pre-Broadway run in Hanover. We saw Ah Wilderness and NightMust Fall, Pygmalion and Arsenic andOld Lace. We laughed at Love Rides theRails, so enormously popular it was revived the next year, and we loved My Sister Eileen. The Interfraternity Play Contest survived; the Experimental Theater didn't.

From 1943 through 1945 we had the V-12 Navy here, and again The Players produced as if there were no war. Mary Morris came to Hanover to play her original role in Double Door, Prof. George Frost's students and colleagues screamed their pleasure as he took Alexander Woolcott's part in The Man Who Came to Dinner and Ann Hopkins Potter took the highly professional lead in Blithe Spirit. We were our own USO and Warner's magic could make us forget for an evening that a war was waiting for that enthusiastic sailor-collared audience in Webster Hall.

The V-12 not only made up the important part of the audience. They also took part in the work of The Players and over that four-year period "the average yearly number of students directly connected with The Players was approximately 400," Warner recalls.

In 1942 he moved away from the English Department where he had been first an instructor, then a professor, and was named "Director of Dramatic Production and of the Concert Series," to which was added in 1946, Graduate Manager of the Council on Student Organizations. George Schoenhut was Acting Technical Director while Henry Williams was on war leave, and Walter Roach had joined the staff as Assistant Director, and head of publicity for The Players and COSO.

Slowly things came back to normal. Winter Carnival resumed. The Experimental Theater revived. And the neverquite-dead dream of a new theater seemed not impossible. A new committee took over, headed by Russell Larmon '19, and Warner's long overdue millennium seemed in sight - then the North Koreans invaded South Korea and we were back to square one again.

The Larmon Committee was stubborn and persevered though the times were not auspicious. And at long last, in 1956, the idea of the Hopkins Center took shape, in the imagination and plans of a new architect, Wallace A. Harrison. This time all that Warner had ever wanted seemed within reaching distance and in May 1957 he could say: "One of the reasons we have such poor theater facilities is that we have lived for about 30 years under the curse of quite optimistic pros- pects of having a new theater. . . . Just as we would reach a point where we felt that we could not put up with this situation any longer and would have to make some expensive alterations in Robinson and Webster Halls, a new committee would be appointed to plan a theater. . . . We felt we could sweat it out for another two years when we would have some- thing really good. The result has been [that] the halls that were here in 1928, and even at that time were inferior to those of most high schools in the country, are what we are working with in 1957. ... In the past at Dartmouth one hand of art has never known what the other hand was doing. In the Hopkins Center we cannot escape each other, even if we should want to. We will have here for the first time the opportunity to show our students how the arts complement each other and have affected our cultures since the beginning of time."

So, in 1960, he assumed his new title, Director of the Hopkins Center. He spent the next year visiting other institutions and cultural centers, checking his own ideas against theirs, consulting not only with the architect but closely with John R. Scotford Jr. '39, the principal staff member in charge of cultural exhibits and special projects, and discussing plans and possibilities with a distinguished advisory committee of actors, producers, directors, and playwrights.

Six and a half years have passed since that memorable November 8, 1962 when Dartmouth kept its 34-year-old promise to Warner and officially opened the doors of the Hopkins Center to an eager, curious public. Speakers at the dedicatory exercises noted that the "true significance of the Center, though presently glimpsed, will not be understood until some years have passed, just as the role of Baker Library in Dartmouth life could not be fully appreciated when it was dedicated in 1928."

Those years have passed. We have begun to know what Hopkins Center means, not just to the College and to Hanover, but to the wider world around us. Here, more than anywhere else, is now the heart of the College, the Center around which its extracurricular life revolves. -The building now belongs to Dartmouth and the future begins today," Warner said in 1962. "With your participation and support... the Hopkins Center will continually add new dimensions to liberal learning and bring, throughout the years to come, honor to the man who so richly deserves this honor, Ernest Martin Hopkins."

What he did not say, but what we can now say for him is that every aspect of the Center, all its functions and cultural riches, the new opportunities it has given to our lives in the Upper Valley, all bear the stamp of the stubborn persistence of one man who never forgot his dream, never completely despaired of attaining it, and never, under however difficult circumstances, compromised with excellence. And in Dartmouth's long, 200-year history, no one man has given more pleasure to more people than has Warner Bentley in his 41 years of distinguished service to the College and the community around it.

1931: Warner Bentley, Eileen McDaniel, and Abner Dean '31, members of the castof "Topaze," one of the early plays in which Warner was both actor and director.

1946: Warner (r) and Technical DirectorGeorge Schoenhut supervising make-up inthe cramped quarters of Robinson Hall.

1956: Hopkins Center was in the offingbut Warner was still carrying The Players onward in the same old quarters.

Hopkins Center became a reality at longlast, and Warner as its Director proudlyshows newsmen some of its features.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureMutual Sensitivity Wins the Day

May 1969 By JOHN DICKEY -

Feature

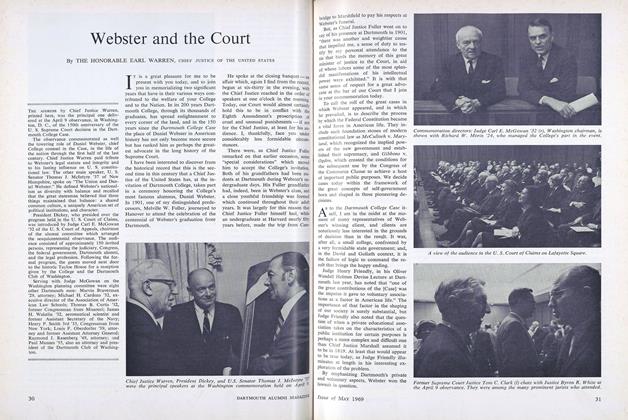

FeatureWebster and the Court

May 1969 By THE HONORABLE EARL WARREN -

Feature

FeatureMay 17 Event to Salute Eleazar's Starting Point

May 1969 -

Books

BooksERNEST HEMINGWAY: A LIFE STORY

May 1969 By JEFFREY HART '51 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1969 By CHRIS KERN '69 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1934

May 1969 By STANLEY H. SILVERMAN, WILLIAM S. EMERSON

MARGARET BECK McCALLUM

-

Books

BooksTHAT GIRL OF PIERRE'S,

December 1948 By MARGARET BECK MCCALLUM -

Article

ArticleIt's a Small Town . . . With a Large Legacy

JANUARY 1964 By MARGARET BECK MCCALLUM -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth's First Lady

NOVEMBER 1965 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Books

BooksDEBRIS.

NOVEMBER 1967 By MARGARET BECK McCALLUM -

Books

BooksSHIFTS OF BEING.

JULY 1968 By MARGARET BECK MCCALLUM -

Article

ArticlePeriod Furnishings Sought for Dan'l Webster Cottage

November 1968 By MARGARET BECK MCCALLUM

Features

-

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH'S ALUMNI RELATIONS

APRIL 1959 -

Feature

FeatureTHE THEME IS CHANGE

April 1962 -

Feature

FeatureConserver of the Crafts

JANUARY 1972 -

Feature

FeatureFROM THE DESK OF THE PRESIDENT

APRIL • 1985 -

Feature

Featurenotebook

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By LAURA DECAPUA PHOTOGRAPHY/TUCK -

Feature

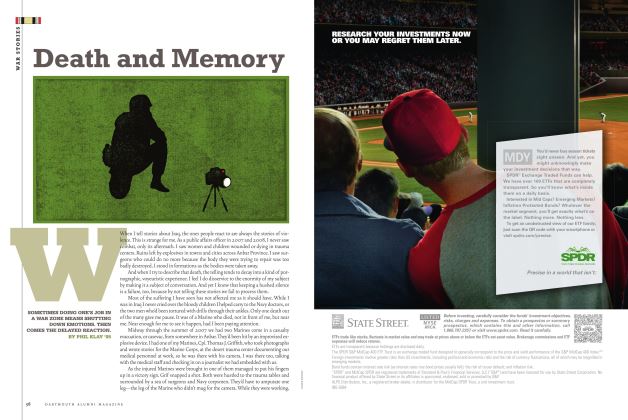

FeatureDeath and Memory

Sep - Oct By PHIL KLAY ’05