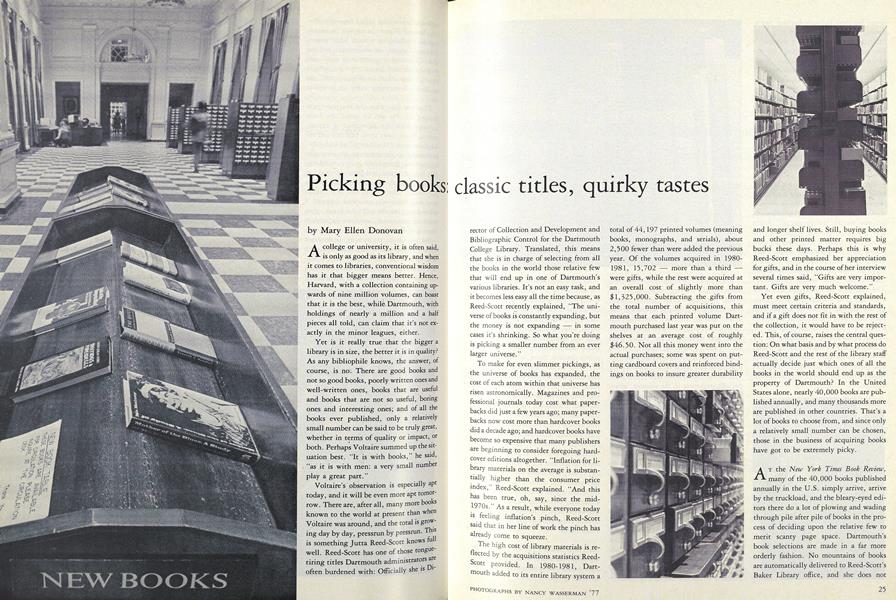

A college or university, it is often said, is only as good as its library, and when it comes to libraries, conventional wisdom has it that bigger means better. Hence, Harvard, with a collection containing upwards of nine million volumes, can boast that it is the best, Dartmouth, with holdings of nearly a million and a half pieces all told, can claim that it's not exactly in the minor leagues, either.

Yet is it really true that the bigger a library is in size, the better it is in quality? As any bibliophile knows, the answer, of course, is no. There are good books and not so good books, poorly written ones and well-written ones, books that are useful and books that are not so useful, boring ones and interesting ones; and of all the books ever published, only a relatively small number can be said to be truly great, whether in terms of quality or impact, or both. Perhaps Voltaire summed up the situation best. "It is with books," he said, "as it is with men: a very small number play a great part."

Voltaire's observation is especially apt today, and it will be even more apt tomorrow. There are, after all, many more books known to the world at present than when Voltaire was around, and the total is growing day by day, pressrun by pressrun. This is something Jutta Reed-Scott knows full well. Reed-Scott has one of those tonguetiring titles Dartmouth administrators are often burdened with: Officially she is Director of Collection and Development and Bibliographic Control for the Dartmouth College Library. Translated, this means that she is in charge of selecting from all the books in the world those relative few that will end up in one of Dartmouth's various libraries. It's not an easy task, and it becomes less easy all the time because, as Reed-Scott recently explained, "The universe of books is constantly expanding, but the money is not expanding - in some cases it's shrinking. So what you're doing is picking a smaller number from an ever larger universe."

To make for even slimmer pickings, as the universe of books has expanded, the cost of each atom within that universe has risen astronomically. Magazines and professional journals today cost what paperbacks did just a few years ago; many paperbacks now cost more than hardcover books did a decade ago; and hardcover books have become so expensive that many publishers are beginning to consider foregoing hard cover editions altogether. "Inflation for library materials on the average is substantially higher than the consumer price index," Reed-Scott explained. "And this has been true, oh, say, since the mid 1970s. As a result, while everyone today is feeling inflation's pinch, Reed-Scott said that in her line of work the pinch has already come to squeeze.

The high cost of library materials is reflected by the acquisitions statistics ReedScott provided. In 1980-1981, Dartmouth added to its entire library system a total of 44,197 printed volumes (meaning books, monographs, and serials), about 2,500 fewer than were added the previous year. Of the volumes acquired in 1980 1981, 15,702 - more than a third - were gifts, while the rest were acquired at an overall cost of slightly more than $1,325,000. Subtracting the gifts from the total number of acquisitions, this means that each printed volume Dartmouth purchased last year was put on the shelves at an average cost of roughly $46.50. Not all this money went into the actual purchases; some was spent on putting cardboard covers and reinforced bindings on books to insure greater durability and longer shelf lives. Still, buying books and other printed matter requires big bucks these days. Perhaps this is why Reed-Scott emphasized her appreciation for gifts, and in the course of her interview several times said, "Gifts are very important. Gifts are very much welcome."

Yet even gifts, Reed-Scott explained, must meet certain criteria and standards, and if a gift does not fit in with the rest of the collection, it would have to be rejected. This, of course, raises the central question: On what basis and by what process do Reed-Scott and the rest of the library staff actually decide just which ones of all the books in the world should end up as the property of Dartmouth? In the United States alone, nearly 40,000 books are published annually, and many thousands more are published in other countries. That's a lot of books to choose from, and since only a relatively small number can be chosen, those in the business of acquiring books have got to be extremely picky.

AT the New York Times Book Review, many of the 40,000 books published annually in the U.S. simply arrive, arrive by the truckload, and the bleary-eyed editors there do a lot of plowing and wading through pile after pile of books in the process of deciding upon the relative few to merit scanty page space. Dartmouth's book selections are made in a far more orderly fashion. No mountains of books are automatically delivered to Reed-Scott's Baker Library office, and she does not spend her days furiously turning pages, tossing those books she likes in a large "IN" basket, throwing those she doesn't like out the window. Instead, she explained, decisions about which books Dartmouth should buy are made by a staff of roughly 20 librarians who act as selectors. The selectors, in turn, base their decisions on recommendations from faculty and students, but principally on reviews, particularly reviews in professional journals. "Essentially," Reed-Scott elaborated, "we take the universe of what there is and break it down into subjects and then assign the subjects to the selectors depending on their individual interests and areas of expertise."

The subject areas into which the universe is broken down, Reed-Scott said, "more or less correspond to departments at the College, or programs at the College, or subjects within the programs." Right now, she said, there are 50 subject areas overall, but "these 50 are guideposts rather than rigid categories, and within many subject areas are sub-categories. Archaeology, for example, is broken down into classical and New World archaeology. And then there are subjects not on the list but which fit into a variety of areas. Energy, for example, is not on our list. If a book deals with the economic aspects of energy, it would be included within the subject of economics. If it's about the political processes having to do with energy, it would be included under government. The intent is that the subject categories should reflect the subject emphasis at the College."

Reed-Scott, pointing out that "our main concern is being responsive to user needs," emphasized that "ideally, all the selectors will be talking to faculty and students, getting constant feedback from them about changes in fields and what the needs and interests of the library users are." There's a standing request that the faculty make recommendations about acquisitions, and "some faculty members are very active," Reed-Scott said. "This is especially important in the sciences, where publications are often very expensive" and esoteric as well.

Often, however, books are acquired simply on the basis of written reviews. In short, if a book gets a good notice in a professional journal, Dartmouth will probably give it a place in its library system. Sometimes, though, an author's reputation alone will suffice as the basis for a book purchase. "If Paul Samuelson comes out with a new book," Reed-Scott explained, "you'd better just buy it without reading the reviews first." Sometimes books are purchased because another reputable library has purchased them. "Harvard Business School puts out a list of new acquisitions," Reed-Scott said, "and our feeling is that if Harvard Business School bought a book on management, then it's probably a book we should buy, too."

As Reed-Scott sees it, the hardest task of the selectors is not deciding which books to acquire but which ones to get rid of — or, to use librarian lingo, "de-acquire." Last year, Dartmouth discarded 976 books, some because duplicate copies were acquired, others because they were in poor shape, and still others because they had grown obsolete. Since, as Reed-Scott noted, "This collection started when Wheelock came here with his Bible and bottle of rum," one could easily argue that many of the books in the Dartmouth collection are obsolete. Then again, one could also argue that those books that seem to some obsolete, archaic even, are precisely what give a long-standing collection its flavor and special value. "Obviously," Reed-Scott said, "a collection like this has grown over time, and a certain amount of pruning is necessary to keep it at a level that meets current user needs. But weeding is almost harder to do than selection. You never know what a user may be looking for, and it may be that an old book of the type that we would not buy today will turn out to be just what a user needs."

Mary Ellen Donovan '76, a frequent contributor, wrote "Hard times in the pressure cooker, about students seeking counseling, in the Decernber issue.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature1850: the crisis of Union 'No sir! No sir! There will be no secession'

March 1982 By Michael Birkner -

Feature

FeatureThe naivete of nuclear rivalry

March 1982 By George Kennan -

Feature

Feature'One day it came to me: sherry for breakfast was a good idea.'

March 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleSomeone wrote them, but did anyone read them?

March 1982 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1954

March 1982 By John L. Gillespie -

Class Notes

Class Notes1959

March 1982 By William G. Long

Mary Ellen Donovan

-

Feature

FeatureThe Lady and the Truckers

October 1978 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeaturePornography in Our Time

October 1980 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureHard times in the pressure-cooker

DECEMBER 1981 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY WOMEN?

OCTOBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan -

Feature

FeatureOn Building Community

DECEMBER 1982 By Mary Ellen Donovan