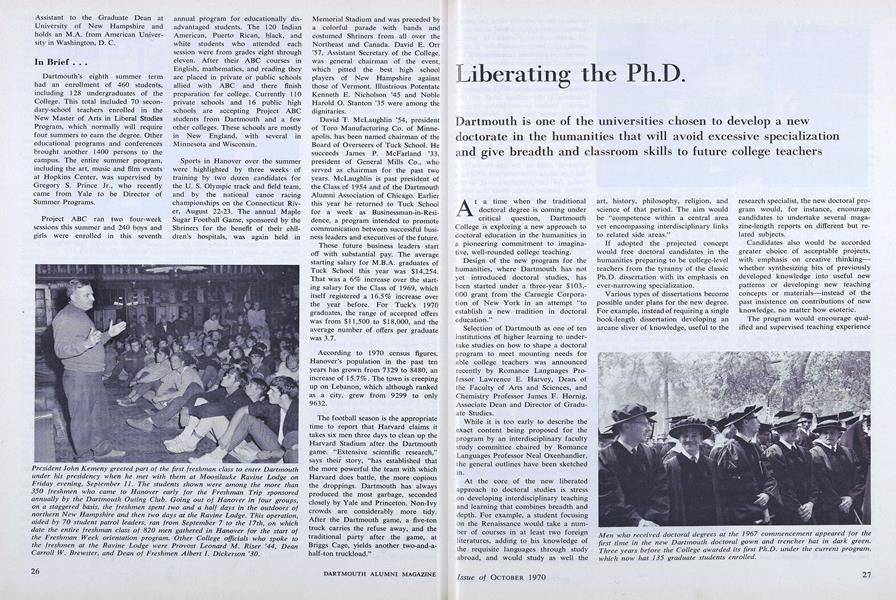

Dartmouth is one of the universities chosen to develop a new doctorate in the humanities that will avoid excessive specialization and give breadth and classroom skills to future college teachers

At a time when the traditional doctoral degree is coming under critical question, Dartmouth College is exploring a new approach to doctoral education in the humanities in a pioneering commitment to imagina- tive, well-rounded college teaching.

Design of the new program for the humanities, where Dartmouth has not yet introduced doctoral studies, has been started under a three-year $103,- 000 grant from the Carnegie Corpora- tion of New York in an attempt “to establish a new tradition in doctoral education.”

Selection of Dartmouth as one of ten institutions of higher learning to under- take studies on how to shape a doctoral program to meet mounting needs for able college teachers was announced recently by Romance Languages Pro- fessor Lawrence E. Harvey, Dean, of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and Chemistry Professor James F. Hornig, Associate Dean and Director of Gradu- ate Studies.

While it is too early to describe the exact content being proposed for the program by an interdisciplinary faculty study committee chaired by Romance Languages Professor Neal Oxenhandier, the general outlines have been sketched in.

At the core of the new liberated approach to doctoral studies is stress on developing interdisciplinary teaching and learning that combines breadth and depth. For example, a student focusing on the Renaissance would take a num- ber of courses in at least two foreign literatures, adding to his knowledge of the requisite languages through study abroad, and would study as well the art, history, philosophy, religion, and science of that period. The aim would be “competence within a central area yet encompassing interdisciplinary links to related side areas.”

If adopted the projected concept would free doctoral candidates in the humanities preparing to be college-level teachers from the tyranny of the classic Ph.D. dissertation with its emphasis on ever-narrowing specialization.

Various types of dissertations become possible under plans for the new degree. For example, instead of requiring a single book-length dissertation developing an arcane sliver of knowledge, useful to the research specialist, the new doctoral pro- gram would, for instance, encourage candidates to undertake several maga- zine-length reports on different but re- lated subjects.

Candidates also would be accorded greater choice of acceptable projects, with emphasis on creative thinking— whether synthesizing bits of previously developed knowledge into useful new patterns or developing new teaching concepts or materials—instead of the past insistence on contributions of new knowledge, no matter how esoteric.

The program would encourage qual- ified and supervised teaching experience as well as the acquisition of practical competence in at least two foreign languages through Dartmouth’s over- seas language facilities. Further, active utilization of Hopkins Center is antici- pated in order that candidates might re- late their studies to the creative and performing arts to fashion a scholar- ship that lives, perhaps even sings. It is envisioned that normal duration of the program would not exceed four years.

To distinguish the new approach from the traditional and indeed to dramatize the reforms being forged, the new program, if adopted, would lead to the degree of Doctor of Arts, rather than the established and strongly en- trenched Doctorate of Philosophy.

The desire to differentiate in name as well as substance has been underscored by the faculty study group which stated in its initial proposal that “most gradu- ate programs in the humanities are seriously flawed, characterized by ex- cessive concentration in narrowly de- fined fields; neglect of the fundamental relatedness of the humanities; emphasis on research that has little inherent in- terest, value or relevance; lack of serious preparation in the nature and skills of teaching; and failure to pre- pare graduate students for the wider competencies needed by a society that is moving toward mass higher educa- tion.’

Discussing the project as director of graduate studies. Dean Hornig stressed that Dartmouth nevertheless has undertaken a formidable task.

“We are committed,” he said, “to create the D.A. as a parallel, not a subordinate, degree. Our program must be such that it will raise the Doctor of Arts degree to a place right along- side the Ph.D.”

Acknowledging that earlier efforts elsewhere have fallen short of this goal, Dean Hornig expressed confidence in the current enterprise, declaring, “I think the nation is ready now for a Doctorate of Arts.” As evidence, he cited both the recent recommendations of the Council of Graduate Schools of the United States in support of this approach and the Carnegie Corpora- tion’s grant of seed money to generate sound D.A. programs and to implement them.

Several factors have encouraged op- timism, including the current challenges to traditional Ph.D. concepts accom- panied by a sense in many quarters that to meet the needs of higher education in the nation, a shift to another kind of quality doctoral program in addition to the Ph.D. is called for.

In recent months, for example, gov- ernment sponsored research on cam- puses and in federal agencies has been reduced, often sharply, and industry has been retrenching, particularly in re- search and development. Thus, a large segment of the market has dried up for the traditional research-trained and oriented Ph.D.’s. Indeed, for the first time, the Ph.D. in some fields is actu- ally in oversupply.

On the other hand, Dean Hornig ex- plained, the increasing need for people trained beyond high school in all areas of society, from business to govern- ment, has been matched by growing enrollment pressures on community col- leges and state universities.

These twin developments presage a mounting demand for the well-prepared teacher-scholar, capable of stimulating teaching at the college level yet ade- quately trained in scholarship to grow in knowledge over the years and to keep pace with the state of his art.

To members of the Dartmouth faculty who have been thinking along these lines for several years, reaching back to the introduction of the doctoral pro- gram in math at Dartmouth early in the last decade, the time seems to have come for the promulgation of a new degree parallel to the Ph.D. but differ- entiated from it by the greater stress placed on preparation for teaching than for research.

A similar concern prompted the Car- negie Corporation, with its devotion to the excellence of American education, to decide to underwrite studies of vari- ous reforms and innovations in doctoral education at Dartmouth and nine other colleges and universities including Brown, University of Wiscon- sin, the University of Michigan, and Claremont Graduate School. Other Car- negie grant recipients will not neces- sarily concentrate on the humanities, however.

“From the very beginning, all our doctoral programs have been biased in the direction of training students with greater breadth than is traditional, and in a way which expresses special con- cern for the preparation of college teachers.” Dean Hornig said. “In the areas of science and mathematics we decided to do this within the tradition of the Ph.D. degree both because we thought it was possible and because we felt that in this way we could contribute to a needed reform and reorientation of the Ph.D. In the Humanities, I believe that both the need for reform and the inertia o'f tradition are so great that it may be wisest to accomplish our goals under a new degree, the Doctor of Arts.”

Dean Hornig stressed that the Dart- mouth program still had several hurdles to clear. First, he said, the blueprint designed this summer by Professor Oxenhandler’s committee and now un- dergoing final drafting must be ap- proved by the Humanities Division of the faculty, the Council on Graduate Studies, the entire faculty of Arts and Sciences, and the Trustees before it becomes a permanent part of the Dart- mouth academic program. Then, he said, it must evoke signs of acceptance in the academic marketplace. In that context, the Dartmouth study commit- tee’s confidence in its proposed product is indicated by its plan to “provide an opportunity for a substantial fraction of the D.A. students [at Dartmouth] to teach in the normal rank of assistant professor for the usual term of a few years after receiving their D.A. de- grees.” While the committee expressed the belief that further advancement of Dartmouth D.A.’s at Dartmouth would not usually be sound without their hav- ing gained further teaching experience at other institutions, it said the Dart- mouth plan envisioned that D.A.’s from other reputable colleges and univer- sities would compete on an “equal basis with Ph.D.’s for positions, advancement and tenure.”

“Dartmouth’s commitment to this aspect of the program should be a powerful argument against the conten- tion that the Doctor of Arts is a ‘second rate’ degree,” the faculty study group has written.

Contingent on passing these tests on schedule. Professor Oxenhan- dler estimates that the first stage of study and planning could be completed during the fall term this year. If approved, pre- liminary implementation would begin in the fall of 1971 with the enrollment of a first contingent of six to seven D.A. candidates to test the program.

If all goes well for them, a second “class” of perhaps a dozen might be enrolled in 1972 with the humanities program reaching a “steady state” of 30 to 40 students working for the D.A. degree in the humanities at Dartmouth. There are currently about 100 students in the doctoral programs under the faculty of arts and sciences, mostly in the sciences plus psychology in the social sciences. A total enrollment of about 300 is targeted as Dartmouth extends doctoral studies in the social sciences and to the humanities.

Although the proposed D.A. program represents a new departure, it is in significant ways an extension of inter- disciplinary programs instituted earlier at Dartmouth at both the baccalaureate and master’s degree level, in conform- ance with long-range policies set forth in 1966 in a joint report of the Council on Graduate Studies and the Committee on Educational Planning and over- whelmingly voted by the faculty.

Some time ago, for instance, a Center for Comparative Studies was inaugu- rated in the Humanities and Social Sci- ences with faculty drawn from all major departments in the divisions so that already the humanities faculty has had considerable experience in the inter- disciplinary approach in both single courses and in major study programs.

Further experience has been or is being gained in the Science and Social Science Divisions through a new En- vironmental Studies Program, the Com- parative International Studies Program, the Black Studies Program, the Asian Studies Program, and the Outward Bound term. Meanwhile, College Courses 1 and 3, the latter initiated last year by President Kemeny to bring the computer to bear on social prob- lems, both underline a trend toward crossing the lines of individual disci- plines in specific courses.

Meanwhile this summer, Dartmouth introduced a summer-term graduate program for secondary school teachers leading to the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies (MALS), again stressing the interdisciplinary approach and breadth in course content. For in a world of rapidly expanding and special- ized knowledge, the teacher’s role must include the capacity to synthesize and relate to give to education at all levels its full meaning and import.

In addition to Professor Oxenhandler and Dean Harvey, members of the Doctor of Arts study committee are: James Epperson, Assistant Professor of English and chairman of the Humani- ties Division; Edward Bradley, Associ- ate Professor of Classics and Director of the Dartmouth Foreign Study Pro- gram; Stephen Nichols ’5B, Professor of Romance Languages and chairman of the Comparative Literature Program; Hans Penner, Associate Professor of Religion and chairman of the Depart- ment of Religion; Werner Kleinhardt, Assistant Professor of German; Jon Appleton, Assistant Professor of Music; and Franklin Robinson, Art Instructor.

Until recent years Dartmouth’s in- volvement with the doctoral degree was sporadic and never substantial. Although the Trustees voted approval of the Ph.D. degree about 1895, only seven earned doctorates were awarded in the ensuing 65 years. Again with Trustee approval, the Ph.D. program was revived in the fall of 1962 and the first doctorate in the current series was conferred at the 1964 commencement. Except for psy- chology in the social sciences, all of Dartmouth’s present doctoral programs are in the sciences—biological sciences, physiology-pharmacology, mathematics, physics, engineering, chemistry, and geology. Last June, 22 doctorates were awarded, and for the current academic year it is expected that 135 graduate students will be enrolled in the various doctoral programs.

Men who received doctoral degrees at the 1967 commencement appeared for thefirst time in the new Dartmouth doctoral gown and trencher hat in dark green.Three years before the College awarded its first Ph.D. under the current program,which now has 135 graduate students enrolled.

Prof. James F. Hornig, Associate Dean of the Faculty and Director of GraduateStudies, sees the projected new Doctor of Arts degree as one that will in timetakes its place beside the traditional, specialized Ph.D.

James Bryant Conant, President Emeritus of Harvard University, who now makeshis home in Hanover, speaks to secondary-school teachers enrolled in the College’snew Master of Arts in Liberal Studies program, begun this summer.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEleazar Is Outdone

October 1970 By Charles Jay Kershner -

Feature

FeatureThe Dickeys Get Resettled

October 1970 -

Article

ArticleDear Mr. Cunningham . . .

October 1970 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

October 1970 By William R. Meyer -

Sports

SportsBig Green Teams

October 1970 By Jack DeGange -

Class Notes

Class Notes1955

October 1970 By JOSEPH D. MATHEWSON, JOHN G. DEMAS