(with some help from his friends)

THE visit in 1925 of the Oxford University debaters may have provided some impetus to the decision to go ahead with the building of Dartmouth's new library. One of the Oxford speakers, acknowledging the students' welcome, said that he had a special interest in coming to Dartmouth because he had heard that the College had the largest gymnasium and the smallest library of any college in America. "That burned me up," said Mr. Hopkins.

Without any stimulus from the Oxford debaters, however, the Trustees were on the verge of deciding to go ahead with the construction of a million-dollar library, even though the funds for doing so were neither in hand nor in sight. In order to meet Dartmouth's most pressing need "we were going to borrow the money, or beg it, or steal it," Trustee John R. McLane said later.

The Trustee vote, at the October 1925 meeting of the Board, authorized that measures be taken immediately for the construction of a library, and instructed President Hopkins to appoint a committee to study all questions related to the matter. Mr. Parkhurst headed this Trustee committee, which worked closely with the Faculty Committee on the Library, headed by Professor Charles N. Haskins. In addition, Mr. Hopkins named a special committee to determine the needs that the library was to meet and also an undergraduate committee to propose features that the students would like.

With the exception of decades of abortive planning for a student social center, no building at Dartmouth had such a long gestation period as did the library. Talk about it began early in the administration of Dr. Tucker, who expressed the hope to live long enough to see three new buildings at Dartmouth - a gymnasium, an administration building, and a library. He saw two of them, and although the library was not built before his death in September 1926, he at least knew that it was assured through the gift of SI million from George F. Baker. At President Hopkins' inauguration, Mr. Parkhurst said he would be bold enough to prophesy that early in the new administration the College would succeed in building "a college library which shall be the crowning glory of all the buildings we have put up here," and he even went so far as to name it the Tucker Library.

Wilson Hall, erected in 1885 for a student body of 400, was grossly inadequate as a library for 2,000 students, and architecturally it was an unattractive building. It had run out of space, and books were stored in basements and scattered in departments all over the campus. President Hopkins in 1917 had stated that he was opposed to solving the library problem on any minor scale. A cost of $1 million seems to have been in his mind from the very beginning, and although a building of such magnitude delayed things for nearly a decade, his foresight once again was vindicated. Tentative library plans had been sketched over the years by a variety of architects, including Charles A. Rich, John Russell Pope, and Jens Fredrick Larson, the College architect, who did the final design. The Trustees in 1919 had decided to locate the new library "in the center of the square north of the College Green with its principal face to the west." At the time of their 1925 call to action, this decision was reaffirmed, but subsequent planning swung the library's principal face to the south and set the building back so there would be a large expanse of lawn. Mr. Hopkins was proud of the fact that a long period of planning had taken place before the architect went to work.

Mr. Baker's million dollars was announced as an anonymous gift on May 17, 1926. The story of how it came about is one of the most fascinating of the Hopkins administration, although in its frequent telling apocryphal bits have crept in. The three main characters, aside from the donor, were Mr. Tuck, Mr. Thayer, and Mr. Hopkins, and a very effective team they were. In the sequel, Mr. Hopkins and Mr. Thayer had to move deftly and persuasively to save a $1.6-million bequest of Edwin Webster San-born, 1878, who had wanted to give the library in memory of his father and was bitterly disappointed when Mr. Baker's gift killed his dream. Mr. Sanborn had been unwilling to make his gift until he died, and with funds for the library so desperately needed, the President and Trustees decided to go along with Mr. Baker's more timely and more certain offer, come what may.

MR. Tuck and Mr. Baker were friends of long standing, having first known each other as young men in banking in New York. Both were men of wealth, with an interest in philanthropy, although Mr. Baker as one of the founders of the First National Bank of New York was many times richer than his Paris friend. After his first visit to Mr. Tuck in 1922, President Hopkins mentioned Mr. Baker in a letter to Mr. Tuck, and the latter reported a month or so later that he had written to Baker urging an interest in Dartmouth. In June 1923, Mr. Thayer, another close friend, was in touch with Mr. Baker, who told him that he intended to do something for Dartmouth in memory of his uncle, Fisher Ames Baker, an alumnus of the College, Civil War soldier,-and New York lawyer. Baker was devoted to his uncle, who was only three years his senior, and he had walked all the way from his home in Troy, New York, to see him graduated from Dartmouth in 1859. Further discussion of a memorial gift took place when Mr. Baker visited Mr. Tuck in Paris in the summer of 1923. The sum of $50,000 was mentioned and Mr. Tuck, by letter, expressed the hope that he would "double the ante." There was some thought of giving a concert organ for Webster Hall, but by October 1925 Mr. Thayer and Mr. Baker were talking about an endowment fund.

This was the background for the meeting between President Hopkins and Mr. Baker which took place at a Cornell alumni dinner at the Hotel Roosevelt in New York on November 14, 1924. Mr. Hopkins, the principal speaker, sat at the right of President Farrand of Cornell, and Mr. Baker, a trustee and benefactor of the university, sat at Farrand's left. There was not much opportunity for conversation, but after the dinner Mr. Baker invited Mr. Hopkins up to his room, where he brought up the subject of a memorial to his uncle. In his reminiscences late in life, Mr. Hopkins recalled that Mr. Baker asked him what the College could do with $25,000. "Not much," Mr. Hopkins replied. "Why, I thought anyone could use $25,000," said Baker. " Yes, they could," Mr. Hopkins answered, "but that amount wouldn't provide the sort of memorial that would be worthy of your uncle or of you."

The story is told that Mr. Baker sat down the next day and sent Dartmouth College a check for $100,000. The amount is correct, but the fact is that it was a month later, December 16, 1924, when Mr. Baker wrote to President Hopkins saying that he was sending securities worth $100,000 to establish the Fisher Ames Baker Endowment Fund for educational purposes. Mr. Hopkins recalled that in thanking Mr. Baker he decided to press his luck and wrote that he was turning the securities over to the College treasurer "on account." Mr. Baker is reported to have got in touch with Mr. Thayer and asked, "How much is it going to cost me to buy my way out of this situation?"

Mr. Baker now became, in the minds of both Mr. Hopkins and Mr. Thayer, the most promising solution to the problem of how Dartmouth was going to pay for the new library that the Trustees had just authorized. While in London in November 1925, Mr. Thayer wrote to Baker suggesting that he might want to consider giving the library in memory of his uncle. Three months later, President Hopkins wrote to Mr. Tuck, "Mr. Thayer's project, about which I wrote you, moves along gradually, with at least this encouragement, that he hasn't been turned down.... If your own influence is exerted and gets time to have effect, I am allowing myself the indulgence of high hope." And three months after that, the good news was made public. The identity of the donor of a million dollars was kept secret until November, when the Boston Herald made a good guess as to who he was, and Mr. Hopkins confirmed it. The year before, Mr. Baker had given $5 million to the Harvard Business School. He was told, or at least was under the impression, that he was providing a home for the oldest graduate school of business in the country, but Mr. Tuck took delight in claiming that distinction for the school he had founded at Dartmouth in 1900, eight years before the Harvard school was founded, and he never let Mr. Baker forget it.

Construction work on the Baker Library began in the late summer of 1926 and partial use of the building began early in 1928, with the official dedication held in June of that year. George F. Baker, because of illness, was unable to be present at the dedication. He had come to Hanover the previous June to receive Dartmouth's honorary Doctorate of Laws, the first trip he had made to the College since his uncle's graduation 68 years before. In September 1928, however, he made a special visit to see the library, and as he was taken through the building in his wheelchair, with President Hopkins and Mr. Thayer as guides, he expressed himself as delighted with it in every detail. In 1930, the year before his death at the age of 92, Mr. Baker asked to see the library again. Baker Library was a benefaction in which he took great satisfaction and pride, and Mr. Hopkins remembered the tears in the financier's eyes as he looked out at the campus from the library colonnade and spoke of the uncle whose name was now perpetuated in the finest undergraduate college library in the country. On that occasion he said, "Dartmouth is a good college. Everybody speaks well of Dartmouth."

As a banker Mr. Baker was pleased that the cost of the library was right on target - $1,132,000, made up of his million-dollar gift, the earlier fund of $100,000, and $32,000 gained in the sale of his securities. Not so happy was his experience at Harvard, where the cost of the business school ran considerably beyond estimate. He therefore felt that Dartmouth was deserving of something more, and when both Mr. Tuck and Mr. Thayer urged him to provide for the proper maintenance of his building, he was quite receptive and gave another million dollars for its endowment. Announcement of this second large gift was made in February 1930.

The happy outcome of the library project, in its planning for the educational work of faculty and students, its design, and its financing, was due to a remarkable group of men, all working together smoothly and as one in their devotion to Dartmouth. In addition to the Tuck-Thayer-Hopkins team, the work of the Faculty Committee on the Library, and especially that of its chairman, Professor Haskins, was superlative. But the leading role of all must be granted to Trustee Henry B. Thayer, 1879, who was of key importance in the relations with Mr. Baker and who, as chairman of the special Committee on the Construction of the Library, spent innumerable days in Hanover overseeing the progress of the work. After he retired as chairman of AT&T in 1927, he gave most of his time to the library and to other plant developments for which he felt responsible as chairman of the Trustee Committee on the Physical Plant. Mr. Thayer was the spiritual successor to General Streeter on the Board of Trustees, and he and President Hopkins had a mutual affection and harmonious working relationship similar to that of the Streeter-Hopkins alliance from 1916 to 1922. Their one disagreement about the library was over Mr. Thayer's wish to eliminate Wentworth Street at the north end of the College Green. Mr. Hopkins thought this would be detrimental to the town, and no effort was made to close off the street. Butterfield Hall, "the best building on campus," had to be razed and eight other structures had to be moved or torn down to make room for the library, but Wentworth Street survived.

President Hopkins also vetoed somebody's idea that a statue of Diana be placed atop the library tower. His idea of a weathervane with a Dartmouth theme was adopted instead. The one feature of the library for which Mr. Hopkins was .clearly responsible was the chime of bells in the tower. After his visits to Oxford and Cambridge he talked so much of his desire to have more bells at Dartmouth that one of the Trustees said he would put up the money to get some for Mr. Hopkins' sake. The sum of $40,000 was given anonymously in the fall of 1927, and later the donor was identified as Clarence B. Little, 1881. The original idea of having a carillon gave way to the simpler and less expensive idea of a chime of 15 bells. The bells, ranging in weight from 200 to 5,300 pounds, were specially cast by the Meneely Company in Troy, under the supervision of Professors Fred Longhurst and John Poor, who spent the better part of a year learning the art and mechanics of ringing changes on them. Not everybody in town was delighted at first when the Baker bells loudly rang the hours, and later the changing of classes, but now they are an ingrained part of Hanover life and a nostalgic memory for most Dartmouth men.

In a letter in July of 1926, Mr. Hopkins expressed his thoughts about the importance of place and local color in the affection that Dartmouth men have for their college. "My own belief has always been," he wrote, "that in our location, in our history and in our daily life we were susceptible to influences that many another college could not respond to, and that the devotion of alumni was dependent to a degree beyond what they quite realized on the environment and the isolation which gave a special flavor and a special atmosphere to Dartmouth life.

"Personally, I want to give the color of our local life all possible hues and to make associations with the College in the subconscious minds of men who come here fixed and pleasant. 1 want to see the College filled with visible symbols of spiritual and intellectual things, and for the same reason that I want a beautiful Gothic chapel on Observatory Hill, I want a sunset carillon to play just as the sun falls below the Vermont hills and just before dusk comes on."

For what it contributed to the educational work and intellectual life of the College, it would be difficult to exaggerate the importance of the arrival of Baker Library on the Hanover President Hopkins had a justifiable sense of satisfaction and achievement in the library. In his reminiscences, he said, "Achievement of Baker Library was the fulfillment of a large part of my dreams as president of Dartmouth. I came pretty near thinking that my career as a college president, all that I could be expected to do, had been accomplished when we got the library."

When Baker Library opened in 1928 as the repository of the College's 280,000 volumes, no one was thinking of a million volumes or of running out of space. The DARTMOUTH ALUMNI MAGAZINE editorialized: "Dartmouth now has the space to harbor her needful volumes for many years to come, if not for all time." The euphoria of the period is understandable, for never in the history of the College had its primary educational program received such a shot in the arm. The way was clear to implement the goals of the new curriculum, with its emphasis on independent study. One of the peaks of the Hopkins presidency had been reached.

THE solution of Dartmouth's library problem left in its wake the disappointment of Edwin Webster Sanborn of New York, who as early as 1917 had sent a copy of his will to President Hopkins disclosing that he planned to leave his sizable estate to Dartmouth for the purpose of erecting a library in memory of his father, Edwin David Sanborn, 1832, for nearly 50 years a member of the Dartmouth faculty and College Librarian from 1866 to 1874. (Professor Sanborn's wife, Mary Webster San-born, was the daughter of Ezekiel Webster, brother of Daniel.) President Hopkins, who had maintained a steady stream of correspondence with Mr. Sanborn from the beginning of his administration, wrote immediately after the Baker gift to inform 'm that an anonymous donor was providing a million dollars for the library. Mr. Sanborn, angered by what he considered almost a breach of contract on the part of the College, made a tentative offer of $300,000 to preserve the Sanborn name on the library; but Mr. Hopkins replied that the library would have to bear the name of the Dartmouth graduate in whose memory it was being given.

Mr. Sanborn's lawyer, Charles Albert Perkins, was privy to Sanborn's plan to leave his entire estate to Dartmouth, and it was the College's good fortune that he used his influence to bring that about in spite of the library development. Perkins wrote to President Hopkins in June of 1926 that Mr. Sanborn was thinking of changing his will. In this matter, as in his intention to provide Dartmouth with a library, Sanborn was a man of extreme caution who vacillated and then ended up by postponing action. In Hanover, meanwhile, much thought was being given to the idea of having some part of the library named for Professor Sanborn, but this was finally dropped as being unpalatable to both Baker and Sanborn. Mr. Hopkins wrote to Perkins wondering if a Faculty Club would appeal to Mr. Sanborn. Then Mr. Hopkins and Mr. Thayer got their heads together and came up with the winning idea. A library without books is no library; why couldn't Mr. Sanborn fulfill his dream and appropriately honor his father by endowing the purchase of books for all time? Many meetings with Mr. Sanborn ensued, and in the end he was won over to the idea of a book fund. However, he still wanted a building to bear the Sanborn name. Mr. Thayer, ever resourceful, proposed a building for the Department of English, in which Professor San-born had served as Evans Professor and later as Winkley Professor. Mr. Sanborn's reaction was enthusiastic, especially since there would be incorporated into the Sanborn House a replica of the study in which Professor Sanborn had extended hospitality to students at all hours and to men of letters visiting the College.

Mr. Sanborn died March 18, 1928, and left his entire estate to the College, with President Hopkins and Treasurer Halsey Edgerton named as executors. The total amount that came to Dartmouth was $1,655,555. The sum of $10,000 was left to the Dartmouth Outing Club, $344,000 was used to build the Sanborn House, and the remainder went to establish the Sanborn Library Fund. Since the book fund was the principal memorial to his father, Mr. Sanborn left instructions that the English House should be a memorial not only to his father, but also to his mother, Mary Webster Sanborn, and his two sisters, Miss Kate Sanborn and Mrs. Mary Webster (Sanborn) Babcock.

Dr. Tucker had characterized Mr. Hopkins as a gambler, and the whole Baker-Sanborn episode was an example of what he had been wise enough to foresee. President Hopkins took chances, at what seemed to him to be reasonable odds, and the outcome in this case was a magnificent library, a million-dollar fund to maintain it, another endowment fund of approximately $1.3-million for purchasing books, and an attractive home for the English Department. That was an excellent piece of presidential work.

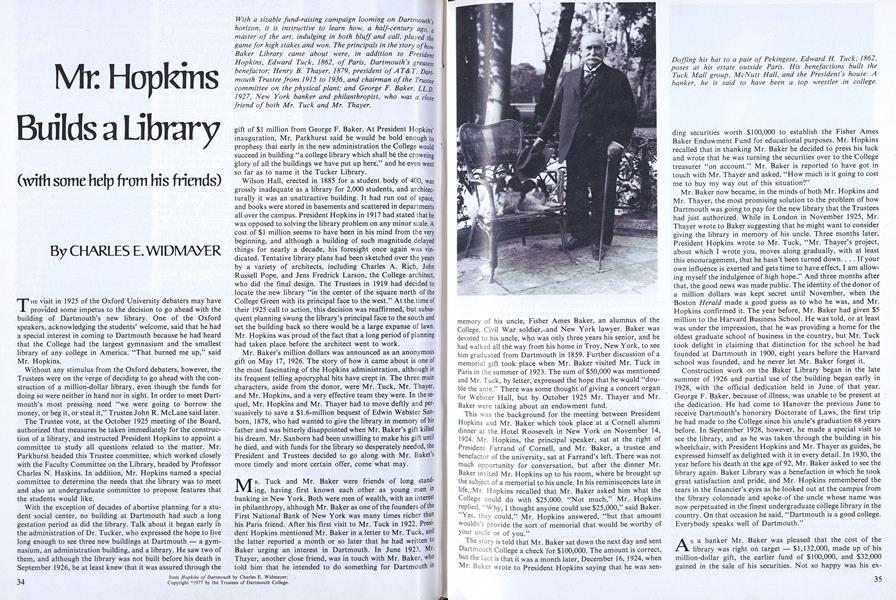

Doffing his hat to a pair of Pekingese, Edward H. Tuck, 1862,poses at his estate outside Paris. His benefactions built theTuck Mall group, McNutt Hall, and the President's house. Abanker, he is said to have been a top wrestler in college.

George F. Baker, who memorialized his uncle with Baker Library, was once described as "omnipotent and enigmatic." LikeEdward Tuck, he was a banker, though it is doubtful he eversaid, as Tuck did, "Never owned a damned bond in my life."

President and Mrs. Hopkins appear with their friend HenryB. Thayer, 1879, at the Madinet-Habu, near Luxor, in 1935.Thayer had influence; when he once mired his car in the Hanovermud, College authorities acted quickly—they paved the street.

With a sizable fund-raising campaign looming on Dartmouth'shorizon, it is instructive to learn how, a half-century ago, amaster of the art, indulging in both bluff and call, played thegame for high stakes and won. The principals in the story of howBaker Library came about were, in addition to PresidentHopkins, Edward Tuck, 1862, of Paris, Dartmouth's greatestbenefactor; Henry B. Thayer, 1879, president of AT&T, Dartmouth Trustee from 1915 to 1936, and chairman of the Trusteecommittee on the physical plant; and George F. Baker, LL.D.1927, New York banker and philanthropist, who was a closefriend of both Mr. Tuck and Mr. Thayer.

from Hopkins of Dartmouth by Charles E. Widmayer; Copyright ©1977 by the Trustees of Dartmouth College.

This article is excerpted from Hopkins of Dartmouth, achronicle of the presidency of Ernest Martin Hopkinsfrom 1916 to 1945, written by Charles E. Widmayer '30,editor emeritus of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE. Commissionedby the Trustees of the College, the illustrated volume ofmore than 300 pages is scheduled for publication in May.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAffirmative Action

April 1977 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureIf you spent the winter in Buffalo, Imagine This

April 1977 By THOMAS SHERRY -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Article

ArticleBetween Seasons

April 1977 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleTopeka Takes On the Hun

April 1977 By NICK SANDOE '19 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1948

April 1977 By FRANCIS R. DRURY JR., LOUIS N. PERRY

CHARLES E. WIDMAyER

Features

-

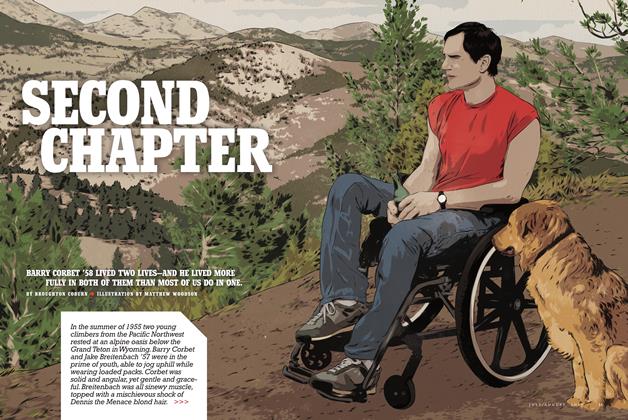

Cover Story

Cover StorySECOND CHAPTER

July/Aug 2013 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

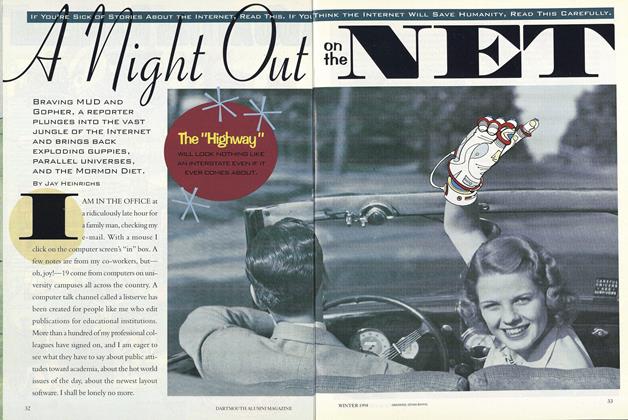

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

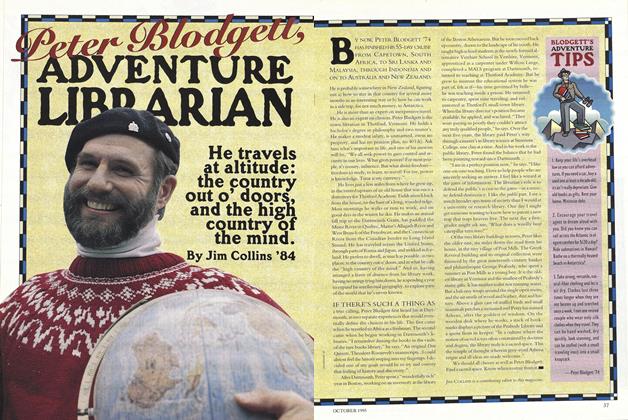

Feature

FeaturePeter Blodgutt, Adventure Librarian

October 1995 By Jim Collins '84 -

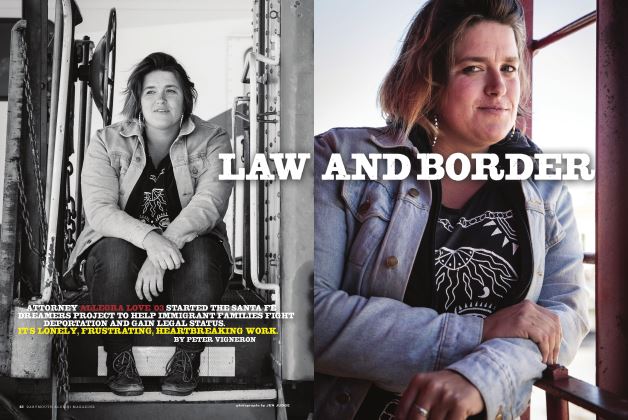

Cover Story

Cover StoryLaw and Border

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2016 By PETER VIGNERON -

Feature

FeatureThe Wooden Shoe: A Commune

May 1979 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

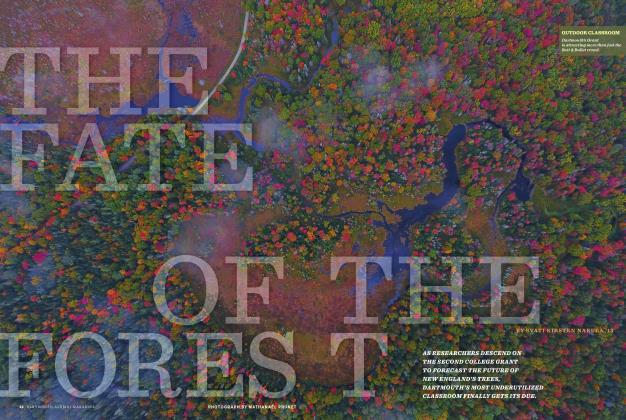

FeatureThe Fate of the Forest

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2020 By Svati Kirsten Narula ’13