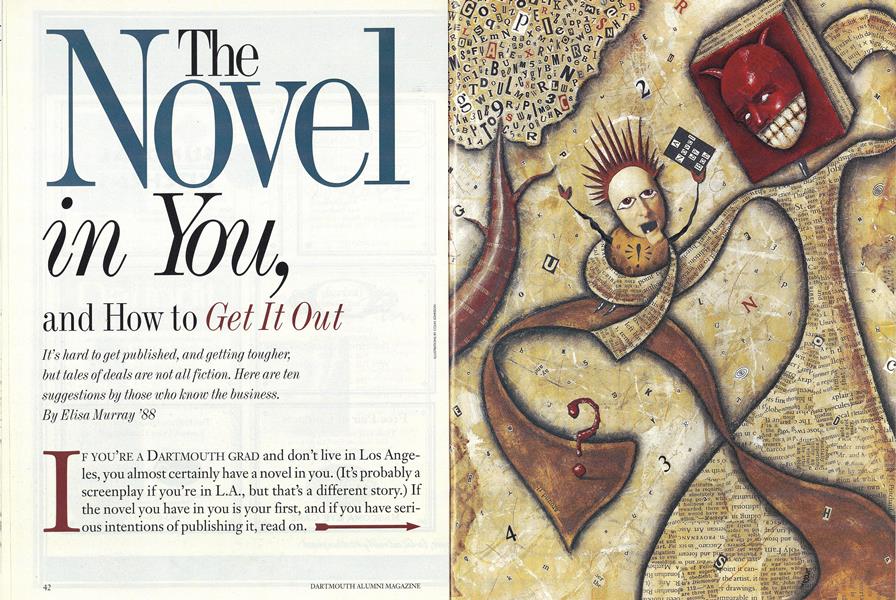

It's hard to get published, and getting tougher, but tales of deals are not all fiction. Here are ten suggestions by those who know the business.

If you're a Dartmouth garad and don't live in Los Angeles, you almost certainly have a novel in you. (It's probably a screenplay if you're in L.A., but that's a different story.) If the novel you have in you is your first, and if you have serious intentions of publishing it, read on.

But try not to get depressed as you do.

It's a literary jungle out there, one that is becoming less penetrable as large publishing houses get bought out by bottom-line conglomerates. Fewer big publishers will take risks on unknown or "mid-list" authors whose books are long shots as bestsellers. "I think you have to be a much better writer than you did ten or 15 years ago," says Boston publisher David Godine '66. "In all the corners a publisher works in, fiction is the most difficult, the most risky, the most fraught with the good and bad. Even when it's good it doesn't always result in sales." The market is particularly difficult for fiction that doesn't fall into a defined category. Genre fiction—detective novels, historical fiction, romance, and the like—has become the staple of a publishing house's earnings, according to New York literary agent A. Richard Barber '62. But even that market is tough to enter.

Don't place all the blame on the publishing houses; they just respond to market trends. Readers used to take pride in tackling a difficult work, observes novelist Ernest Hebert. "It was like cracking a code. You were reading James Joyce's Ulysses, and it was sort of a big deal to figure this thing out," says Hebert, who teaches creative writing at Dartmouth. "Today, readers have no patience for that."

Those readers who like good fiction are having a harder time finding it. The New York Times reviews much less fiction than it used to. High-profile literary magazines, such as Harper's and The New Yorker, are publishing less short fiction a traditional literary proving ground.

So, sure, it's a jungle out there. But some hardy young writers manage to hack it every year. They may succeed with the few large and mid-sized presses, such as Houghton Mifflin and St. Martin, that still take a flyer on an occasional first novel like White Rabbit by Kate Phillips '88 and Unsolicited by Julie Wallin Kaewert '81. In addition, small presses are exploding in number: 6,000 new ones enter the market each year. One of the newcomers is Hardscrabble Books, a division of the University Press of New England owned in part by Dartmouth. Hardscrabblenamed for the fictional town that the writer Corey Ford modeled after Hanover got its start in 1994 when editing heavyweight Phil Pochoda grew "increasingly depressed and disappointed about New York publishing," and, after a career of top positions at Doubleday and Simon & Schuster, moved to the Upper Valley.

So there is hope for the novelist in you provided that novelist is one determined writer. We asked some experts for some tips.

1. Know Your Characters.

When writing his first novel, The Dogs of March, Ernest Hebert spent two hours a day for a year writing a profile of the book's main character, Howard Elman, an ornery, working-class New Hampshire man. Hebert wrote about Elman's daily activities, his friendships with the local "shanty" people, and his hatred of both farmers and yuppies.

2. Nail the Plot Down.

Hebert takes a road trip of several days alone ("who would want to listen to me?"), and dictates the plot of a new novel into a tape recorder. "By the time I get to New Mexico," he says, "I have a pretty good story." Then all it takes is a year or two of writing and revision.

Scott Smith '87 completed a 40-page, single-spaced outline before he wrote a word of his novel, A Simple Plan. He had a good reason: It was a heck of a plot. (Three men find $4 million in the wreckage of a plane. What will they do?)

Not everyone follows this advice. Michael Dorris, for example, plans nothing beforehand. He just lets a plot evolve. "It changes from sentence to sentence. I'm in the middle of a novel right now and I have no idea what's going to happen from one line to the next. It's like telling yourself a story."

3. Write What You Know

That's one cliche that works. Julie Wallin Kaewert '81 followed that advice; she drew on what she observed during her job as an editorial assistant in an English publishing house when she wrote her hit first novel, Unsolicited, a fast-paced, tongue-in-cheek whodunit set in where else? the English publishing world.

4. Get it Right

Michael Dorris took his acclaimed Yellow Raft in Blue Water through at least a dozen drafts. Rewriting is the key to great fiction. "It has to do with the language, with the moving around of the words on paper until they are lapidary, until they resonate, until they have some sort of electricity," says Bruce Ducker '60, author of Rule by Proxy.

Even publication doesn't stop Budd Schulberg '36, author of the 1941 bestseller What Makes Sammy Run, from wanting to revise his prose. "I take a book off the shelf that I've written and I look at it and I say, 'I can't believe I wrote that sentence. I have to fix it.'"

5. Find a Tough Reader.

Dorris says he and wife Louise Erdrich '76 are each other's "nastiest editors." Each author writes 12 or 13 drafts, fueled by the comments of the other. "You must find somebody whose literary aesthetics you respect, who will tell you the truth," advises Dorris. "And you just have to keep doing it, until the words 'but I meant' aren't applicable."

First make sure you're ready for criticism before you show your work, warns Lane Von Herzen '84, whose two novels went paperback. Several fellow students in her M.F.A. program at the University of California, Irvine, made the mistake of getting too much input too soon. "They would lose sight of what their original vision was and never be able to recapture it," she says.

Once you find a publisher, your best reader (and, at first, your most important) might be your editor. Scott Smith rewrote the protagonist of A Simple Plan after the editor told him the character was too cold-blooded. The novel's power, the editor thought, relied on a reader being able to identify with the choices the character makes. So Smith softened it. The result: commercial success and the sale of movie rights, despite some negative reviews.

6. Go to the Smaller Presses.

At the big presses, "largely the only first novels that are published are those for whom somebody at least perceives the possibility of a big hit," says Hardscrabble's Phil Pochoda.

Brace Ducker should know. A "fairly famous" editor at Knopf rejected his fourth novel, Marital Assets, while comparing the style to Jane Austen's. "But God help me," the editor told Ducker. "In this market I wouldn't publish her either."

Debbie Lee Wesselmann '81 didn't even get as far as an editorial conversation. She spent a year and a half looking for an agent for her first novel, Trutor and the Balloonist. She began sending the manuscript herself to smaller publishers. Mac Murray & Beck in Colorado accepted it—one of three fiction books to be published next year by the firm. "Because it's a small press, do get a lot more attention than I would at a major publisher," she notes.

Small presses make sense even for established authors, says Ernest Hebert. "For what my books sell, for a big publisher like Viking or Simon & Schuster, it's not really worth their while. But it's worth UPNE's while; I can make money for them. It's a trend I see: A lot of the smaller publishers are picking up the slack left over by the larger publishers."

7. Sell It Hard.

Send manuscripts to any contacts in the industry—"an editor you met at a party, a former lover who now teaches creative writing at Dingleberry State," says Hebert. He suggests sending a manuscript to publishers one by one. At the same time, send a one-page, well-written query letter to as many agents as sound interesting. Explain what the book is about and why anyone should take you seriously as a writer. Michael Dorris says the selling must continue even after a publisher buys it. "You can't just write it, you have to know how to sell it: readings, a lot of stuff that feels like not what you want to do."

8. Keep Your Day Job.

So recommends Phil Pochoda, who admits that authors who go with small presses tend to get paid less than the usual paltry sum for first authors. So even if you actually get your novel published, and it actually sells pretty well, you probably couldn't live off the royalty.

9. Don't Rest on Your Laurels.

A corollary to the Eighth Publishing Commandment, actually. Evan S. Connell '45 learned it the hard way in 1949, ten years before publication of his first novel, Mrs. Bridge. "When I started out, one of my short stories turned up in Best American Short Stories, in 1949 or something like that, and I thought, oh boy, from now on I'm set...not so at all. It didn't make any difference."

10. Keep Trying. Or, Wiser Yet, Quit.

Connell says he rarely encourages young writers. "People who are going to write are going to do it no matter what you tell them," he says. "The ones who need encouragement shouldn't go into it in the first place, because it's a bitterly discouraging business." Literary agent A. Richard Barber agrees: "The word you'll hear most often is 'no.'"

Robert Eaton Kelley '61 persisted nonetheless, writing three unpublished "modern/postmodern" novels and finally self-agenting his fourth work, The First Book of Timothy—which took 14 years to write. The University Press of New England published it in 1996.

Elisa Murray is a writer based in Seattle, Washington.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

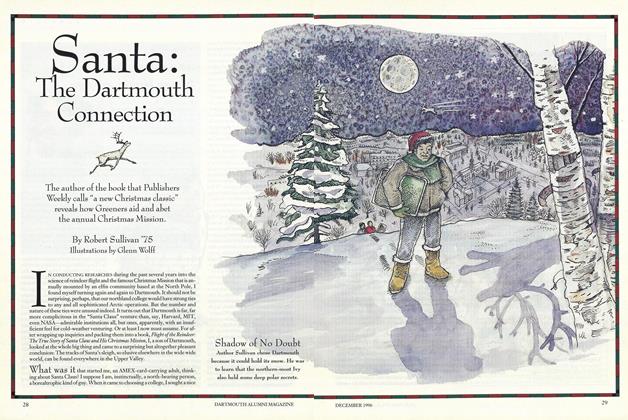

Cover StorySanta: The Dartmouth Connection

December 1996 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

FeatureSHUE HAPPENS

December 1996 By Jake Tapper ’91 -

Feature

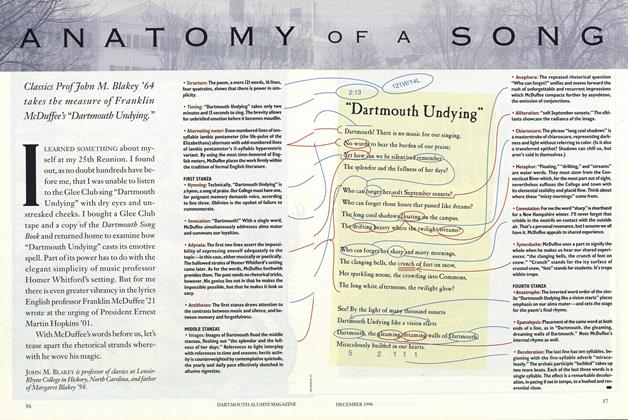

FeatureANATOMY OF A SONG

December 1996 By John M. Blakey '64 -

Article

ArticleA Quiet Greatness

December 1996 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleThose Who Got It Out

December 1996 -

Article

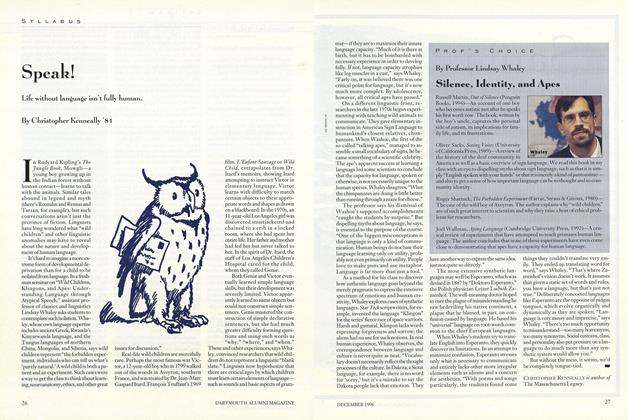

ArticleSpeak!

December 1996 By Christopher Kenneally '81

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRobert S. Oelman '31 Heads Alumni Council for 1954-55

July 1954 -

Feature

FeatureALUMNI SKI WEEKEND

APRIL 1971 -

Features

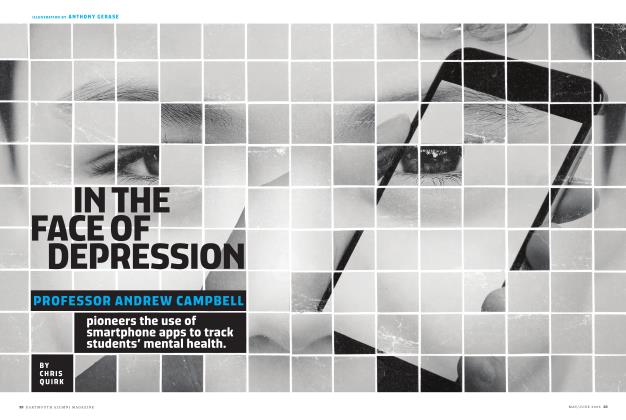

FeaturesIn the Face of Depression

MAY | JUNE 2025 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO BECOME A LAWYER

Sept/Oct 2001 By DANIEL WEBSTER -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May/June 2006 By Gisela Insuaste '97 -

Feature

FeatureClassnotes

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2015 By LIBRARY COLLEGE DARTMOUTH