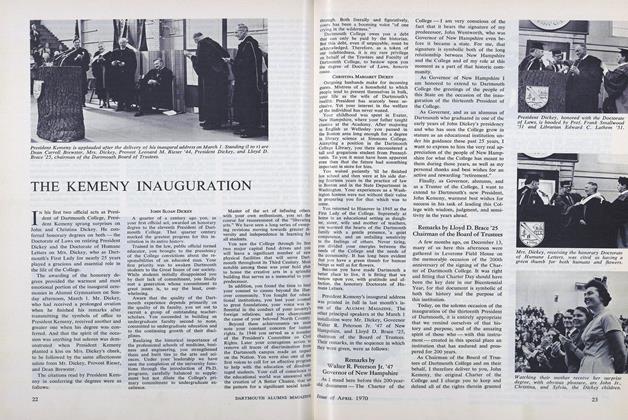

A COLLEGE inauguration is an infrequent thing, especially at Dartmouth; and so, aside from the transfer of a few traditional symbols of the "Wheelock Succession," each ceremony is the product of the style of the participants and of the times. At first thought it is a rather imposing occasion, one where the academic community gathers its lieutenants in their accumulated pomposity to preside over the installation of a new member of the club. But John Kemeny had the good sense to take office quickly and with a cleanness of style which most students applauded.

The ceremony evoked a rare feeling of community among those who were there. The Dartmouth Review caught the mood:

It was billed as a family affair and it certainly was just that, with all the conviviality and good nature the term implies. The largest available segment of the Dartmouth family, the students, were there in unprecedented numbers and unusual dress. They had come to witness the changing of the guard; youth does have a sense of history and they were loving it.

John Sloan Dickey, a remote figure to most students of the past five years, performed his role with extraordinary grace, style, and humor. On an occasion which must have been most difficult for him, he transcended whatever sense of loss he felt in making the occasion meaningful for others. Yet it was not only loss; liberation was equally visible. For many students the ceremony provided the first real sense of community in two or three years. President Dickey received repeated standing ovations not only as a mark of respect but as a tribute to his performance that day. The one constituency which responded with subdued enthusiasm was the faculty.

As the first half of the ceremony belonged to John Dickey the second half belonged to John Kemeny. As one observer pointed out, President Kemeny's maugural address was for internal consumption. Specific and practical, it did not offer broad educational or philosophical vistas, although those elements were not completely ignored. Rather, it approached the particular problems of Dartmouth.

Mr. Kemeny set out his priorities. First, a decent standard of living for all those who work for Dartmouth. Among all those who depend on Dartmouth for their livelihood, the most

ignored - the janitors and secretaries and maintenance personnel - were given particular attention. The quality of student life, the ongoing needs of educational programs, and construction programs were given special attention.

We were warned that "difficult and occasionally painful decisions" would be required and then we were called upon to enter into a 12-month period of "far-reaching debate" and "institution-wide soul searching." And we were told that our new President would make every effort to open the channels of communication so that every member of the community would feel that he has access to the facts. The faculty was served notice that the new President wanted a reorganization of the faculty structure combining the four existing faculties into one facility.

One point that Mr. Kemeny made is worthy of particular attention. He noted that Dartmouth had decided to admit students not only irrespective of their financial situation but even if society had deprived them of an opportunity to attend a first-rate secondary school. "I feel," he said, "that we have a great deal to learn about the education of disadvantaged students. We made some honest starts this year, some of which proved to be false starts, and we hope we will do a great deal better next year. . . . Although we must build a meaningful bridge between where secondary schools left students through no fault of their own and where Dartmouth hopes they can enter, it is not enough to build an educational bridge alone. Unless we can find the means to make these students feel a part of the Dartmouth family, we should not admit them in the first place." He will find that as tough a challenge to meet as all the rest put together.

It was immediately obvious as Mr. Kemeny took over that Dartmouth was in for a very different presidential style. He was seen one evening sitting on the floor at the back of the Top of the Hop listening to a forum on ecology. He held the first of what he promises will be a monthly press conference for the reporters of WDCR and The Dartmouth. It was learned that he plans to set aside weekly office hours for students who wish to visit him and he has made it known that once he has settled into the President's House he wants to meet with groups of students in his home and away from the academic situation.

Although President Kemeny has been a mathematician all of his professional life, his interests and intellect have extended far beyond mathematics or even science alone. He has written a number of education articles dealing with the role of the teacher, the academic structure, and various other aspects of educational policy in an institution such as Dartmouth.

In the two months since his appointment was announced he has been examining proposed changes in all areas of institutional policy. One detects a great faith in reason and the analytical process in the way Mr. Kemeny approaches his work. Solutions can be found if one can sort through the available alternatives quickly enough and apply a clear analysis of the problem at hand in selecting alternatives. It requires a quick and flexible mind. No solution is ruled out because it is new or because it is not easy or because it is not a 100% proposition.

From the evidence available, President Kemeny's rationality is tempered by an understanding of the subjective processes of human nature which must be accounted for. He has been known for being impatient with equivocating colleagues or students, but his inaugural address was a strong sign that he knows the limits of stress in an academic community. A college president in particular has a limited future if he doesn't recognize that fact, since so little of the potential fr leadership is vested in specific powers.

Mr. Dickey touched on this fact during the inaugural ceremonies when he said, "In candor ... I perhaps ought to say to a successor that I hand over a job of unlimited responsibilities with, shall we say, contrary to appearances, something less than a corrupting measure of authority. And yet, good friend and esteemed successor, be not dismayed; as a wise man once said, nothing succeeds like successors."

All of this ... the drive, the confidence in reason, the openness ... has communicated a sense of excitement, especially to the students. There is an anticipation that Dartmouth is on the verge of becoming a more interesting place to live and to learn. The quiet among the students persists; last fall it was a quiet born of weariness from the events of the spring, but it is becoming increasingly a quiet which may be productive of a better academic community. Not that students will necessarily fulfill your expectations or mine, but that they will be finding a community which helps them to go through the intellectual and emotional process which hopefully will free them to be what they will. At this moment the black brothers in particular do not find a sympathetic atmosphere outside the bounds of their own community. Unless Dartmouth can move quickly to make everyone feel a "full member of the entire community" it will lose its self-respect.

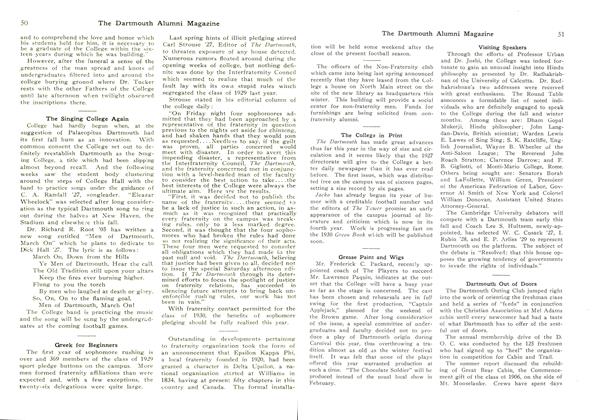

David Brooks '71 of Sigma Alpha Epsilon, resident tutor at the ABC house inHartford, Vt., working with Willie Kasayulie, former student at the ChemawaIndian School in Oregon. Alpha Chi Alpha, Bones Gate, and Sigma Theta Epsilonare other Dartmouth fraternities providing resident and evening tutors for ABCgroups at Lebanon and Claremont, N. Hand Woodstock, Vt.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dilemma of World Power

April 1970 By GENE M. LYONS, -

Feature

FeatureRevival of the M.D. Degree

April 1970 -

Feature

FeatureTHE KEMENY INAUGURATION

April 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe National Scene

April 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

April 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

April 1970 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, GEORGE PRICE

WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70

-

Feature

FeatureThe Making of a Primary Winner

MAY 1968 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

NOVEMBER 1969 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

JANUARY 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

FEBRUARY 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

MAY 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70