A CHANCE FOR THE PENTAGON TO HELP SOLVE SOME DOMESTIC AS WELL AS MILITARY PROBLEMS

MAY 1970 GERALD G. GARBACZ '58A CHANCE FOR THE PENTAGON TO HELP SOLVE SOME DOMESTIC AS WELL AS MILITARY PROBLEMS GERALD G. GARBACZ '58 MAY 1970

A proposal for a Domestic Action Program that will make use of the gigantic Defense Department resources

THE war in Vietnam has proven to be a benchmark for the Defense establishment in the United States. From the end of World War II until the Vietnam war, Defense programs and expenditures were at the top of the priority list of Federal government resource allocations. More importantly these programs were rarely questioned. Primarily because of our involvement in Vietnam, the pendulum recently has swung in the opposite direction. Critics of the Defense Department abound, each with his particular bone to pick. If we were to sum up this collective criticism, the end product would sound like:

Give priority to the solution of domestic, not security oriented, problems.

Reduce the size and power of the military.

Avoid foreign military entanglements.

Decrease the size of the Defense budget and it will be managed more efficiently.

Unfortunately, the worldwide climate does not provide an opportunity for the United States to ignore its commitments. We are not living in the Nineteenth Century when a "Fortress America" was a technological as well as a political possibility. Despite the urgency of our domestic problems, we must face the massive threat poised against us by the Soviet Union. The tremendous strategic offensive and defensive missile forces of the Soviets cannot be discounted. Whether to meet this threat with parity or superiority is the subject of an intense debate. What is not in question is that, in either case, our defense posture will still have to remain extensive.

The essential questions are: What role should we expect the military to play in light of the pressing demands for the limited resources available in the nation? Is there a way that the military's role can be reshaped so that they are less in competition with other segments of our society and more complementary in their use of resources?

Each of the three most recent Secretaries of Defense — Robert McNamara, Clark Clifford, and Melvin Laird — viewed with great alarm the racial/urban crises which have enveloped America during the past decade. Each knew that he administered the largest, most powerful organization in the world and felt that there must be some positive, constructive actions the Department of Defense could undertake to assist in resolving our most pressing domestic problems.

These proposed actions covered a broad spectrum of involvement. The Defense Department's annual purchases of $40 billion could be postured to produce auxiliary social benefits and to stimulate economic activity in disadvantaged areas. The facilities, equipment, and land controlled by the Defense Department could be productively used to solve domestic problems when not being utilized for military purposes. Reserve lawyers, dentists, and doctors could receive training credits by working with the indigent. The thousands of military personnel stationed across the country could become more involved at the local community level in solving social/economic problems. The million men who flow through the military annually could have their skill levels upgraded and our country's human resources would be improved.

The intent of pronouncements by the Secretaries of Defense was often suspect. Conservatives saw the effort as a detraction from the Defense Department's primary role of providing national security. Some liberals assessed the concept as one further step in the military's desire to dominate American society as well as to preserve a large Defense budget. The purpose of this article is to discuss the merits and problems associated with this concept and to illustrate its potential.

THE nation's security rests on a base much broader than its military power. Military power is only one tool in the search for security. Of equal, or greater, importance is the ability of the United States to project a stable society, one in which each citizen has the freedom and opportunity to pursue his personal aspirations.

In many situations the United States hopes to enhance its security by "winning men's minds." The image we project to other nations depends as much on the strength of our internal society as it does on the weapons systems we develop or the number of troops we maintain in our armed forces. If one accepts a broad concept of national security, then assisting in the elimination of the basic causes of internal social problems should become part of the Defense mission.

Historically, the military services have played a significant, although unpublicized, role in implementing domestic policies and improving our society. More military effort has been devoted toward Domestic Action since 1776 than has been devoted to military action. One President remarked during the 1800's that "the ax, pick, saw and trowel have become more the implement of the American soldier than the cannon, musket or sword."

Military medicine has eradicated many endemic diseases in the United States. In 1900 there were 350,000 cases and 35,000 deaths due to typhoid fever. An Army Medical Board, headed by Major Walter Reed, was instrumental in eliminating this health problem. Other military programs uncovered the methods to suppress yellow fever, beriberi, and malaria.

Military personnel on the western frontier often planted and harvested crops for local communities. Officers were frequently the first teachers in many newly established towns. Of the first 36 railroads in the United States, 32 were managed by Army officers, some on furlough, others who had left the service.

The land improvement projects of the Army Corps of Engineers have made a vast impact on the economic development of our country. Since 1824 Army engineers have completed over 3600 major projects, built or improved more than 300 harbors, constructed and maintained over 30,000 miles of coastal waterways.

There are two primary reasons why the military developed this tradition of domestic service. First, in many instances military personnel possessed unique talents and skills which were not in sufficient supply elsewhere in the country. Problems needed to be solved and the nation turned to an available, qualified organization to solve them. Second, the military has a set of values which places a high premium on service and accomplishment of mission, Military personnel not only have been willing to risk their lives in combat to insure the nation's physical security; they also have developed a strong sense of service to compensate for lack of material reward and status during peacetime. Military personnel are oriented toward results, the accomplishment of objectives. A military society rewards accomplishment and places a strong sense of accountability on the individual.

During the summer of 1969 I was associated with a Domestic Action pilot project. One hundred and fifty boys, aged 11-14 from the inner city of Washington, lived for five weeks in a residential camp located on a military base. Although the camp was civilian-directed, the responsiveness, flexibility, dedication to duty, and administrative skills of the military staff proved to be essential elements in the camp's success. These men provided vital, needed characteristics of orderliness and self-discipline; consequently, they became respected examples for the campers.

Although the Defense Department could make a valid case for domestic involvement solely on its responsibility for total national security, there is another reason for involving the Department in domestic problem areas. The Department of Defense by virtue of its size can make a more rapid and profound impact on our society than any other single institution. The Department employs almost five million persons, has assets with an original cost value of a quarter of a trillion dollars, consumes over eight percent of the gross national product, and has an annual procurement budget of over $4O billion.

The conflict in Vietnam overshadows two significant characteristics of the Defense Department — readiness and deterrence. The readiness of the military is essential for the containment of violence. In many instances the speed with which the military can respond will directly determine the degree of escalation which occurs. The size of the military and the resources under its control are based on potential needs. The credible posture of assured nuclear destruction, even in the face of a surprise attack, projected by the United States since World War II has deterred that type of war.

It is unrealistic to assume that all Defense resources are fully employed on a daily basis in peacetime. Only so much time and effort can be devoted to training and preparation. The remainder is an untapped reserve available for immediate application in time of crisis. Some of this reserve, in terms of man-hours or of use of military facilities and equipment, can be applied to domestic problems, while an effective state of readiness is maintained.

To fully comprehend the impact which the Department of Defense could make in a critical domestic problem area, let me illustrate how the Department is assisting in reducing the nation's housing problems and how it could continue to do so in an expanded scale:

• The Department of Defense is the largest single purchaser of housing in the country. Each year approximately 5,000 new family housing units are constructed on military installations. A military base is one of the few locations in the country which has no building codes or zoning restrictions. This situation allows theoretical studies to be physically tested, a possibility frequently not available where building codes exist. The Defense Department is as interested as the private sector in reducing the costs and improving the quality of housing. During the current year, the Department, working closely with experts from HUD and utilizing the results of their theoretical studies, will construct 200 housing units at George Air Force Base using a mobile factory concept which is projected to reduce costs by 20%.

• In the inner city of Washington, Army carpenters, plumbers, and electricians are instructing unskilled school dropouts in the reconstruction of several dwellings belonging to the National Capital Housing Authority. Thus unemployed inner city residents are given the training they need to refurbish their own environment.

• When the Defense Department constructs family housing across the nation, they could combine contracts with local housing authorities, thereby employing economies of scale for both government agencies.

• One of the major policy decisions with respect to housing is the status of the urban slum or black ghetto. Should slums be upgraded into an attractive environment or should residents of the ghetto be dispersed throughout the suburbs, thus forming a more integrated society? Once this policy has been decided, the Department of Defense pro- curement budget could become a powerful vehicle for instituting the policy. Contractors could be given preference for hiring ghetto residents in the ghetto or in the suburbs, depending on the policy. Thus, an economic incentive would be added to political pressure for the acceptance of national policy. The preferences for Defense contracts given to small businesses by Congress established a precedent for this type of action. The merits of assisting fledgling firms overrode the economic advantages of competitive bidding among all firms.

• The Department of Defense must resolve a serious urban encroachment problem during the next decade. Many military facilities are no longer very useful because urban growth has enveloped them. These bases will be declared surplus and disposed of; the Brooklyn Navy Yard was a prime example. Will these bases become planned model neighborhoods or will they merely be absorbed into the existing urban disarray? The methods and criteria which the Defense Department uses to dispose of these installations will be a major factor in determining whether these installations can be used to partially alleviate the housing crisis.

• The Secretary of Housing and Urban Development has clearly indicated that a major problem in achieving the nation's housing goals is an inadequate supply of labor in the construction trades. One of the major contributing factors to this problem is the inadequate and time-consuming apprenticeship program of certain craft unions. During their military careers, many young men receive training and on-the-job experience which may be the equivalent of apprenticeship training. The Department of Defense working closely with the Office of Education and the Department of Labor could certify military training and experience as satisfactorily fulfilling apprenticeship criteria.

• The Department could exert its influence to pressure unions to accept the certification. There is ample precedent for this type of action. Defense contractors are required to meet equal employment criteria prior to securing contracts. Secretary McNamara, concerned about the morale of Negro servicemen, established a program which attempted to persuade landlords voluntarily to desegregate their housing units. This voluntary program was a colossal failure; so he then resorted to coercion by declaring off-base housing off limits to military personnel unless it was integrated. When faced with this pressure, the landlords integrated their units; they could respond to this type of action and still retain social acceptance in their communities. In the same vein, the Defense Department might have to prohibit certain craft unions from participating in Defense contracts unless they accepted Defense apprenticeship certification.

• Each year project officers and other skilled management specialists complete tours of duty which have developed their managerial techniques to a high degree. Frequently, their next assignment makes little use of their project management expertise and is not in a critical capacity. Meanwhile, redevelopment and housing projects languish or move forward slowly and inefficiently because local and state governments do not have enough high-caliber managers to manage them. An exchange program could be established in which military program management experts are loaned on request to other government agencies for a two-year tour of duty. Thus local programs would move ahead through the effective employment of management skills developed and utilized in the Department of Defense.

DESPITE the promise which Defense involvement can bring to our domestic problems, there are some problems associated with the concept.

Probably the most significant potential problem lies in the area of policy involvement. The Defense Department should not establish domestic policies. This role is not part of their mission nor do they have the competences essential to develop these policies. Fortunately, the Nixon Administration has created a policy-making body which can supervise Defense actions in domestic areas — the Urban Affairs Council. A member of the staff of the Urban Affairs Council attends all meetings of the Defense Department's Domestic Action Council and the two staffs work closely together. It is important to recognize that the Secretary of Defense is not a member of the Urban Affairs Council and consequently cannot affect the urban policies developed by the Council.

A second major problem area concerns when and how the Defense Department should become involved in domestic activities. The rule which was proposed by Secretary Clifford and accepted by Secretary Laird is that the Defense Department should become involved only when the activities can be accomplished more efficiently or effectively by the Defense Department than by other agencies. The following examples illustrate this concept:

• In many cases Defense resources are not in constant use, but are required to meet peak seasonal or cyclical needs. If these resources can be employed to solve domestic problems, then civilian agencies can allocate their resources to other problems. As an example, a municipal government recently spent $250,000 to purchase acreage for a summer camp for 100 disadvantaged children. Nearby was a military base which had deactivated areas which would have been ideal for a camp.

• Under Secretary McNamara the Department of Defense began Project 100,000. This program permits the Armed Forces to recruit annually 100,000 men who do not meet normal accession standards. Prior to Project 100,000 military service was a paradox to ghetto youths who lacked education, vocational skills, and incentives. Many of these youths viewed the military as the one institution which could provide them with the essentials to become productive citizens, yet the military's admission standards denied them the chance to gain these essentials. Project 100,000 opened the door to these youths and the Armed Forces developed specialized remedial tools to provide additional training for the Project 100,000 men. These tools have been very successful; reading levels of semi-literate recruits have risen significantly. To date, no public school system has approached the Defense Department concerning the possibility of using these tools in a conventional school system. These unique educational resources have not come close to reaching their potential audience.

A third problem associated with Defense Domestic Action is funding. While some benefits of Defense Domestic Action can be secured on a "cost-free" basis through the spin-off of normal Defense activities, the vast majority do require some incremental funds. In order to qualify within Secretary Laird's cost-effectiveness standards, the incremental investment should produce sizable benefits. Nevertheless some funding is required.

In order to insure that a Defense Domestic Action program is the best way of attacking a problem, it should be compared to other alternative programs for the same area. This means that the Defense program should be justified before the appropriate Congressional committees dealing with the domestic subject, not the Armed Services Committee. Whenever feasible, incremental costs associated with Defense Domestic Action programs will appear in the responsible agency's budget and reimbursement will be requested from the agency. Thus, marginally productive programs cannot be hidden in a massive Defense budget nor can Domestic Action programs be used to perpetuate high Defense budgets.

Even though this approach has merits, it also has drawbacks. Other agencies may be reluctant to admit that the Defense Department has the best method or available resources for dealing with a particular problem. The "not invested here" attitude could prevent an enthusiastic endorsement of the Defense program. The Department of Defense is not popular with the personnel in many domestic agencies. Its motives are suspect; its resources envied; and its competence questioned.

ANOTHER significant problem associated with Defense Domestic Action programs is the internal attitude of the military services. Many members of the military perceive Domestic Action activities as directly conflicting with their basic military value systems. Their perceptions of national security do not encompass Domestic Action projects. Secretaries Laird, Clifford, and McNamara have all emphasized that Defense Domestic Action programs must not reduce military effectiveness. Rather than using imagination to insure that Domestic Actions are consistent with military effectiveness, some commanders use military effectiveness as the reason for precluding all positive domestic programs. These same officers view riotcontrol training and domestic order as perfectly acceptable military functions. Instead of trying to assist in preventing disorder, they tend to view (somewhat with a sense of pride) their role as the final mechanism to preserve order "when the civilians have failed in their missions." It has been said, not totally facetiously, by a civilian manager in the Department of Defense, that it is much easier to secure a helicopter to spray tear gas on demonstrators than it is to secure a bulldozer to assist in redevelopment.

The military must be won over to the side of positive Domestic Action. Several of the members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff recognize the merits of Domestic Action. Their support is essential; however, the entire military establishment's attitude needs to be affected. The most important stimulus for securing military acceptance of an expanded, active participation in domestic activities lies in their incentive and reward system. Involvement in domestic projects needs to be encouraged, not discouraged. There are a variety of techniques available to produce this conversion. The broad postgraduate education system created by the military since World War II for career officers needs to stress the potential and rationale for domestic involvement. Perhaps even the sacrosanct fitness report and promotion system will have to be adjusted to reward participation in successful domestic programs.

Because of its size the Department of Defense is a very difficult institution to change. Unless the Secretary of Defense takes a deep personal interest in Domestic Action, it stands little chance of becoming part of the way of life in the Pentagon. The Secretary has to do more than promulgate general policy guidance. He should actively follow individual projects, monitor their results, and insist on innovation. However, the demands on him and on his immediate subordinates (who sit on the Domestic Action Council) are so extensive that they cannot be expected to have time to perform much work themselves. They require the services of a full-time staff devoted to the concept of Domestic Action and unafraid of the system's resistance to change. Unless such a group continually prods the conscience of the Pentagon, domestic activities will never get off the ground. The only "overrun" in this situation will be the unfulfilled potential for service to the country. Some members of the military do not recognize that they are citizen-soldiers. They view civilian society as a foreign environment which is entered only on retirement. This attitude is in direct conflict with traditional American values and our social system.

In an era when military leaders have a profound influence on the Federal government's allocation of resources, it is absolutely essential that they have an appreciation, gained through some involvement, of the reasons underlying competing demands for resources. Other societies were endangered when their military leaders were not closely attuned to all the problems and aspirations of their citizens. Unless we can permit military personnel to serve their country through participation in the reduction of domestic problems, we are in danger, in the words of the Kerner Commission, of "moving toward two societies" — one civilian and one military. This type of polarization can be prevented if the military is allowed to accept responsibility for those domestic activities to which they can bring a demonstrated capacity for accomplishment.

"Some members of the military... view civiliansociety as a foreign environment"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Great Love Affair Between Students and Films

May 1970 By MAURICE H. RAPF '35 -

Feature

FeatureProject IMPRESS

May 1970 By JOANNA STERNICK -

Feature

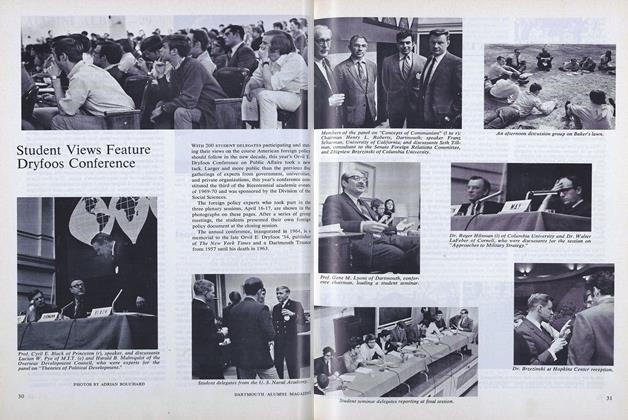

FeatureStudent Views Feature Dryfoos Conference

May 1970 -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1970 By WINTHROP A. ROCKWELL '70 -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

May 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Class Notes

Class Notes1921

May 1970 By HAROLD F. BRA MAN, WILLIAM M. ALLEY

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHomage to the great god Pigskin: One hundred years of Ivy rivalry

OCTOBER 1972 -

Feature

FeatureSecond Panel Discussion

October 1951 By ARTHUR L. GOODHART -

Feature

FeatureSelf-Evident Truths

May 1976 By ARTHUR M. WILSON -

FEATURES

FEATURESNo Limits

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2022 By CHRIS QUIRK -

Feature

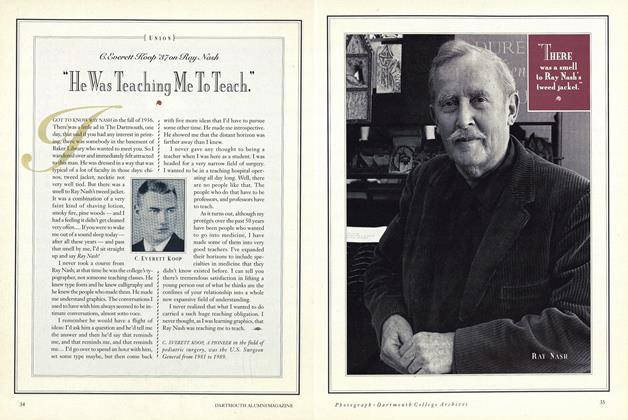

FeatureC. Everett Koop '37 on Ray Nash

NOVEMBER 1991 By Ray Nash -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIntelligent Life

MARCH 1995 By Sasha Verkh '95