Although Dartmouth is best known for its prowess in winter sports, some of its most notable athletes have been summer Olympians: Earl Thomson '20, for instance, or Frederick Taylor '25, or Gerald Ashworth '63. One of the hopefuls for the upcoming Games in Korea is Mike Fadil '85, holder of the Ivy League record in one of track and field's most unusual sports: the steeplechase.

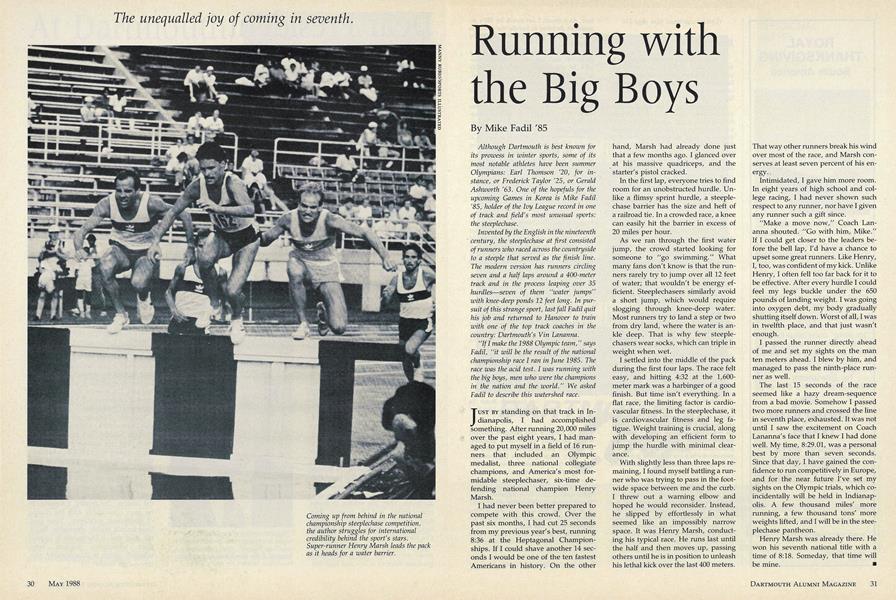

Invented by the English in the nineteenthcentury, the steeplechase at first consistedof runners who raced across the countrysideto a steeple that served as the finish line.The modern version has runners circlingseven and a half laps around a 400-metertrack and in the process leaping over 35hurdles—seven of them "water jumps"with knee-deep ponds 12 feet long. In pur-suit of this strange sport, last fall Fadil quithis job and returned to Hanover to trainwith one of the top track coaches in thecountry: Dartmouth's Vin Lananna.

"If I make the 1988 Olympic team," saysFadil, "it will be the result of the nationalchampionship race I ran in June 1985. Therace was the acid test. I was running withthe big boys, men who were the championsin the nation and the world." We askedFadil to describe this watershed race.

JUST BY standing on that track in In- dianapolis, I had accomplished something. After running 20,000 miles over the past eight years, I had man- aged to put myself in a field of 16 run- ners that included an Olympic medalist, three national collegiate champions, and America's most for- midable steeplechaser, six-time de- fending national champion Henry Marsh.

I had never been better prepared to compete with this crowd. Over the past six months, I had cut 25 seconds from my previous year's best, running 8:36 at the Heptagonal Champion- ships. If I could shave another 14 sec- onds I would be one of the ten fastest Americans in history. On the other hand, Marsh had already done just that a few months ago. I glanced over at his massive quadriceps, and the starter's pistol cracked.

In the first lap, everyone tries to find room for an unobstructed hurdle. Un- like a flimsy sprint hurdle, a steeple- chase barrier has the size and heft of a railroad tie. In a crowded race, a knee can easily hit the barrier in excess of 20 miles per hour.

As we ran through the first water jump, the crowd started looking for someone to "go swimming." What many fans don't know is that the run- ners rarely try to jump over all 12 feet of water; that wouldn't be energy ef- ficient. Steeplechasers similarly avoid a short jump, which would require slogging through knee-deep water. Most runners try to land a step or two from dry land, where the water is an- kle deep. That is why few steeple- chasers wear socks, which can triple in weight when wet.

I settled into the middle of the pack during the first four laps. The race felt easy, and hitting 4:32 at the 1,600- meter mark was a harbinger of a good finish. But time isn't everything. In a flat race, the limiting factor is cardio- vascular fitness. In the steeplechase, it is cardiovascular fitness and leg fa- tigue. Weight training is crucial, along with developing an efficient form to jump the hurdle with minimal clear- ance.

With slightly less than three laps re- maining, I found myself battling a run- ner who was trying to pass in the foot- wide space between me and the curb. I threw out a warning elbow and hoped he would reconsider. Instead, he slipped by effortlessly in what seemed like an impossibly narrow space. It was Henry Marsh, conduct- ing his typical race. He runs last until the half and then moves up, passing others until he is in position to unleash his lethal kick over the last 400 meters. That way other runners break his wind over most of the race, and Marsh con- serves at least seven percent of his en- ergy.,

Intimidated, I gave him more room. In eight years of high school and col- lege racing, I had never shown such respect to any runner, nor have I given any runner such a gift since.

"Make a move now," Coach Lan- anna shouted. "Go with him, Mike." If I could get closer to the leaders be- fore the bell lap, I'd have a chance to upset some great runners. Like Henry, I, too, was confident of my kick. Unlike Henry, I often fell too far back for it to be effective. After every hurdle I could feel my legs buckle under the 650 pounds of landing weight. I was going into oxygen debt, my body gradually shutting itself down. Worst of all, I was in twelfth place, and that just wasn't enough.

I passed the runner directly ahead of me and set my sights on the man ten meters ahead. I blew by him, and managed to pass the ninth-place run- ner as well.

The last 15 seconds of the race seemed like a hazy dream-sequence from a bad movie. Somehow I passed two more runners and crossed the line in seventh place, exhausted. It was not until I saw the excitement on Coach Lananna's face that I knew I had done well. My time, 8:29.01, was a personal best by more than seven seconds. Since that day, I have gained the con- fidence to run competitively in Europe, and for the near future I've set my sights on the Olympic trials, which co- incidentally will be held in Indianap- olis. A few thousand miles' more running, a few thousand tons' more weights lifted, and I will be in the stee- plechase pantheon.

Henry Marsh was already there. He won his seventh national title with a time of 8:18. Someday, that time will be mine. ■

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryJonathan Corncob and Other Almost Classics

May 1988 By Noel Perrin -

Feature

FeatureAt Dartmouth, the Intellectual Is on the Margin

May 1988 By Karen Avenoso '88 -

Feature

FeatureDear President Freedman...

May 1988 By Tom Bloomer '53 -

Article

ArticleAlumni Writers Approve Review's Tongue-Lashing

May 1988 -

Lettter from the Editor

Lettter from the EditorResponse: The Real Women's Issues

May 1988 By Mary G. Turco -

Article

ArticleProfessor William Cole: "Fifty Years From Now They'll Be Talking About This Course"

May 1988 By Jay Heinrichs

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryJames Forrestal 1915

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

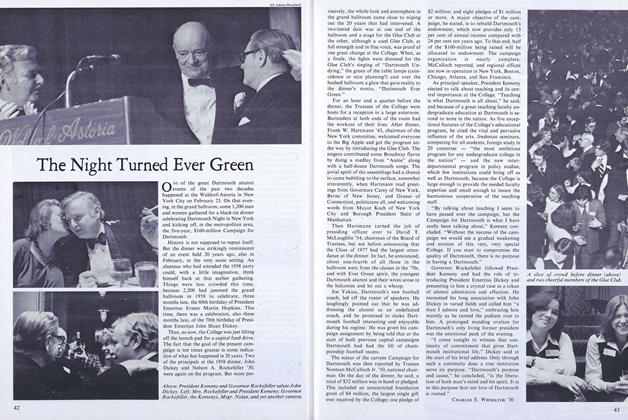

FeatureThe Night Turned Ever Green

APRIL 1978 By CHARLES E. WIDMAYER '30 -

Feature

FeatureInvocation

JULY 1971 By CHARLES F. DEY '52 -

Feature

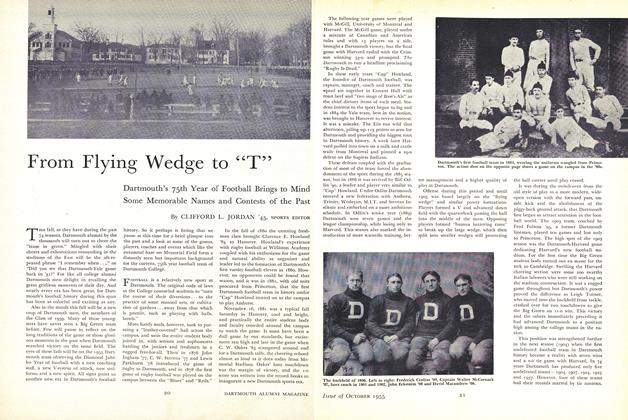

FeatureFrom Flying Wedge to "T"

October 1955 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45, SPORTS EDITOR -

Feature

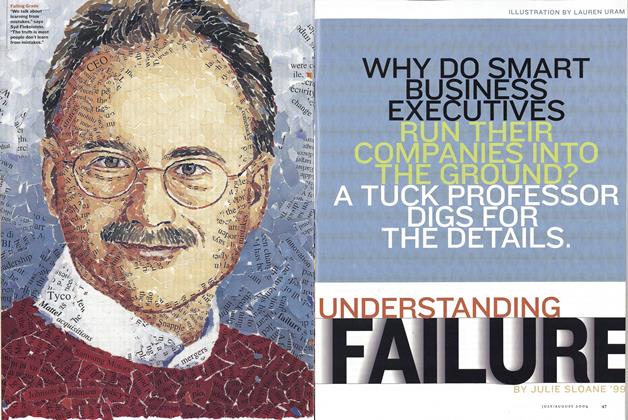

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

Jul/Aug 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL