THE COMMENCEMENT ADDRESS

ALL mapmakers," says Saul Bellow's wise old Sammler, "should place the Mississippi in the same location, and avoid originality. It may be boring, but one has to know where he is."

The Indians knew where they were before we uprooted them. They stood simply on the earth of their beliefs, resisting the outrageous benevolence and the gospel-greed of the land-hungry whites. It was in a mood of such benevolence that we once tried to persuade the Shoshones of Wyoming to renounce their Earthmother and retire to semi- deserts where they would learn the art of farming under conditions that doomed them to failure. The agent explained his proposals, the tribe debated them. Then Chief Washakie rose. Mustering what English he had, he said simply, "God damn a potato!" - and adjourned the council. He meant, of course, that buffalo-hunters had better things to do than to grub for tubers like a lot of Paiutes. But that was not all. He also meant what Smohalla, the prophet of the Columbia, said in answer to the same demands: "It is a bad word that comes from Washington, always. You ask me to cut grass and make hay and sell it and be rich like the white man. But how dare I cut my Mother's hair? Shall I take a knife and tear my Mother's breast? Then when I die, she will not take me to her bosom to rest. My young men shall never work! Men who work cannot dream, and wisdom comes in dreams."

Aristocratic words. Too aristocratic for the whites, who took them as mere Indian shiftlessness. But behind them lies all of Indian life. They are statements of the spirit, and the spirit's priorities. Washakie had nothing against potatoes. He was a prudent man, a chief, and even Shoshones must eat. But there are some things a man will not eat. To the Indian the dream was the bearer of his identity; it made him a member of the great community outside himself — the friendly dead, the Great Spirit, the powers of the place, and what we would now call the unconscious and the past. In the dream he encountered the Other - something kin to himself, but also alien, and unmistakably there. The young Indian on the verge of manhood waits, and the dream comes to him like a revelation, both outward and inward. It speaks his name and tells him what his ripening powers are - the otter's grace, the gravity of the elk. The dream seals the maturing powers of the dreamer with the welcome of the larger world, the great chorus of the others. Everything the Indian meant by his humanity, every link with the other things of the world, was violated by that stupid word from Washington.

My Mississippi is on the map. Education is a spiritual affair. An old and familiar text, but it is where we begin. "The mind of this country," said Emerson, a contemporary of Smohalla, "being taught to aim at low objects, feeds on itself. Our culture has truckled to the times. It is not man- worthy. If the vast and spiritual are omitted, so are the practical and the moral. We teach boys to be such men as they are. We do not teach them to aspire to be all they can." Smohalla and Washakie tell the story of the victims who suffered the inhumanity of the failed education Emerson describes. For Emerson the failure is a matter of low ends. There is no hint in his words of the "others." The individual is isolated in his lonely will.

The American tradition of voluntarism and individualism, combined with "manifest destiny" created the arrogance Smohalla resented. It is a disease chronic with us, whose most obvious form is racism. But it is our standard educational practice still. I think of my own state of Texas where Spanish-speaking children must strike in order to speak their native language on the schoolgrounds. Or of Viet Nam. Or anywhere in America at any time. We cannot abide the encounter with the "other." We evade it always. When school- children study foreign countries they study Switzerland or Norway - the assimilable, the not-so-strange. We do not teach children Hamlet or Lear because we want to spare them the brush with death. And we steadily deprive them of the encounters which might educate them, which might give them their names and a community with others.

A classicist would call this disease hybris. Inaccurately translated "pride," hybris has a constant aura of violation. It suggests processes gotten out of hand, things spilling over natural limits, violating the physical space of others. It is indeed an annihilation of others. In fifth-century Attic law hybris means "rape." A garden which is "lush" has hybris

it is a discontented garden, a garden with megalomania, aspiring to be a jungle. The opposite of hybris is sophrosyne. This means but "the skill of mortality" - the self-knowledge of the man who knows that he is doomed, who accepts his limitations. He has encountered "the other" and therefore treats other men with the compassion his own doom claims from them.

Now, in the Greek view, hybris can be met in only two ways. First, by the actual experience of disaster, the bitter tragic doom that teaches the man of hybris who he really is, his nakedness and nothingness. The second way is by education, which teaches sophrosyne through the tragic spectacle of doomed hybris. I believe that the essential social purpose of Greek tragedy - which was deliberately subsidized by the state for the instruction, not the amusement, of the people was to educate a proud people, a people prone to hybris, in sophrosyne. Euripides in his Trojan Women, for instance, is trying to elicit from his audience the compassion so achingly absent in the play and in Athenian foreign policy.

Hybris, then: an expansive, aggressive denial of the other. Immured in folds of self-sufficiency, the man of racist hybris is unreachable, almost unteachable. He can kill with something like negligence'—with the barbarous bland irritability of the massacres at My Lai and Wounded Knee.

The ancient world knew mass man too, but he is essentially modern. And no wonder. We have maximized hybris. There is no saving skill, no sophrosyne, to resist it with. If we could only find or set a limit to our unimpeded will! If we could only encounter the other! But America is no longer a country where the other is easily encountered. We have brushes, but few encounters. The past is being everywhere erased; the earth has few powers we respect. As for other men, they are almost all unapproachably isolated. "No man is an island, entire of himself," said John Donne, who could not have imagined this America. Young and old simply fail to meet. Therefore they cannot qualify each other, cannot compose an arc of common humanity. Florida, is one vast geriatric spa, rabid with fear and hatred of the young. The public schools, the high schools, are huge peer-group prisons, patrolled by armed adults. Everywhere ghettos. Old and young, rich and poor, black and white, living and dead - not sensible pluralisms, but segregated parts of a once common life! If there are encounters, they occur at the barriers, and they are violent or cold. And meanwhile in Washington the elected warlocks turn human differences into antagonistic blocs, chanting of unity but exploiting divisiveness in an orgy of bad faith. "It is a bad word that comes from Washington always." And as the encounters grow rarer and colder, as the "other" disappears from embrace and sight, the demonologies become more virulent and explosive. Outside the enclosure any evil can be believed of anybody, because there is nobody human there. Inside the barrier reef, the coral hybris grows, taking its inward toll of the psyche.

Hybris nearly incorrigible, nearly hopeless! What then can educators do? Are we doomed to go on toiling forever behind, like Homer's goddesses of healing Prayer in the wake of Ruin, trying to undo the desolation? There are many - an increasing number - who believe our crisis is so vast, and our margin of time so short, that we must turn all our energies to politics. I share their fears. If ever we needed real political vision and leadership, the time is now. But there is little sign of either. And even if we had vision, we would still need educators who believe in the goodness of what they do, who still see their work as a necessary task of the spirit. The opportunities, the contexts, exist. The hunger for education is everywhere. The schools and colleges are one of the last places where real encounters can occur. Here there is still a hope of making a self in collaboration with others.

IF we have maximized hybris, how can we increase sophrosyne?

I want to propose that we deliberately make the one great reform it lies in our power to make. Formal education cannot improve until we recognize and act upon our recognition - that the liberal arts and teacher education are one and the same thing. Only when the colleges renounce their professionalism and devote themselves seriously - that is, with all their resources - to the education of teachers will public education ever become the instrument of a great democratic culture.

The stakes are high. The most revolutionary risk ever run by this country was its commitment to universal education. Only one other society in the history of mankind has taken a similar course, and that was Athens, which in the fifth century deliberately attempted to democratize a great aristocratic ethos. Ultimately, that attempt was a failure - the most brilliant failure in human history. Our own commitment is now in great danger. On the one hand, it has been betrayed by an insidious elitism - the elitism of the learned professions - which has made liberal education the servant of merely professional ends and disavowed students with other interests. On the other hand, it has been betrayed by a class of pseudo-professionals who, by means of their own illiteracy, turned the public schools into nurseries of a massive illiteracy - an illiteracy which threatens to destroy the republic.

"No amount of reflection," writes R.P. Blackmur, has deflected me from the conclusion that the special problem of the humanities in our generation ... is to struggle against the growth of the new illiteracy and the new intellectual proletariat." The new illiteracy represents those who have been given the tool of reading ... without being given either the means or skill to read well or the material that ought to be read. The habit of reading in the new illiteracy is everywhere supplied by a press and, I would add, schools almost as illiterate as itself. It is in this way that opinion, instead of knowledge, has come to determine action; the inflammable opinion of the new illiterate is mistaken for the will of the people, so that arson becomes a chief political instrument."

This is why we must summon every effort to the task of educating a nation. We have almost no time left. And education is the incomparable priority. It will need generosity of spirit, active intelligence at the top of its bent, and an openness to the perplexity of being and remaining human in these terrible times. The ultimate danger is further condescension, taking the quality out of our thought when we want to persuade others of the urgency of what we have to say. In an illiterate society, the teacher's literacy may be the only literacy in sight. In a world of militant hybris, the teacher may be the only evidence of achieved humanity.

My proposal is simplicity itself. Let the liberal arts colleges train teachers. Six years ago James Conant suggested precisely this - that the colleges be licensed to prepare and certify primary and secondary school teachers. A few colleges have responded, cautiously and unenthusiastically; so far as I know, no major university has seriously considered it. The fact is not surprising; the snobbery of research and the low status of teachers made the idea one which no lustrous institution would consider. Nonetheless, the colleges have everything to gain by vigorously entering into teacher education. They still claim to confer a unique education, and, despite the encroachments of professionalism, they still assert that they are not prep-schools for graduate study. Much of this, of course, is rhetoric. Yet I can think of no better way for the college to preserve its integrity than by training teachers. For in carrying out this new mission, it would perhaps be possible, as it now is not, to impede the corrosive professionalism of the departments. Left to themselves and deprived of any larger end, the disciplines will tend to flourish for their own sakes. And students will claim, and rightly, that their education has been sacrificed to a professionalism that has nothing to do with education.

More decisive is the satisfaction which this generation might find in teaching the very young. Their dissatisfactions with their own education apply even more forcefully to the primary and secondary students. Here, in the terrible bleakness of the schools — not merely ghetto schools, but almost all schools - is where the talents and skills of this generation might really flourish. Here, if anywhere in our culture, is where sympathy and compassion and understanding would produce results; here is where sophrosyne, properly fostered, might take root and grow. Here is where the future will be created or destroyed. Generosity of spirit is crucial; but so is bright, clear, nimble, trained intelligence. Teachers have for too long been recruited from among the not-too- bright, and then stultified by the colleges of education. Admittedly, the material awards of teaching are low, but surely this hardly matters for a generation that has largely turned its back on the traditional conventions and comforts of the American middle-class. What is needed is a signal, an institution prepared to give direction and purpose to generous energies in search of satisfaction. The response, I believe, would be nothing short of overwhelming. And if the signal were given by a distinguished university, it would encourage others to take this necessary risk.

BUT even teaching may not be enough. We are so divided now; our illiteracy is so explosive! This is why teaching must be seconded by another great effort, also educational and no less massive than the first, but aimed at coping with the problems created by the lack of political leadership and the disappearance of those institutions - press, family, church - that once supported the work of formal education.

I have in mind the creation of what I call "a university of the public interest." By this I mean a university dedicated to the advocacy of just those public interests - in education, in health, in social justice, in the environment - that are now endangered by organized greed, professional mindlessness, miseducation, and policies of "benign neglect" - that is, by the national vacuum of value and vision. In short, a modern Socratic university for a mass society, an organization of professionals determined to apply their skill as effectively as possible, and to educate their students by enlisting their efforts in the same mission. By "Socratic" I want to suggest both power of intellect and the conscience of knowledge. A university of the public interest would educate by the power and example of its own advocacy, by its visible pertinence to our problems, because it addressed itself, with the full power of active mind, to the public's sense of justice, compassion, beauty, in the hope of thereby eliciting or strengthening the skills that now seem paralyzed or lost. Lost, because unaddressed, because daily diminished, stultified with half-truths and politic lies, by being always addressed in terms of its basest, least generous, powers. You appeal to the powers you hope to enlarge. You cannot educate except by speaking to your student's virtue, to his hope of being more than he is. The spirit must be visible and articulate or it will not be believed. And in a mass society the individual tends to become invisible; this is why we need spiritual institutions and concerted commitments. We need to syndicate Ralph Nader. A few examples:

Professional reform. The effort to create a university of the public interest is nearly synonymous with professional reform. The nation has no future worth contemplating unless we can product a different kind of professional: a lawyer whose client is the public, an architect who is more than the cagey flunky of his client, an engineer sensitive to other factors than cost. We also must have new para-professionals. Reformers of course are very active in professional education already; Dartmouth itself has been one of the bolder pioneers. But the pace of reform needs quickening. We can best do this, I suggest, by openly establishing the university as a corporation for the public interest. As a patron, the university would help the new professional to win eventual public support for what is, after all, public service. The chief obstacle is now the difficulty of finding a base of operations and institutional support. Even more important, the university might provide the public education which all programs involving the public interest must have. Reform of the legal profession looks eventually, of course, to reform of the laws. And reform of the laws is a task of political education.

Hence, a national newspaper. We will not have a literate society, until every citizen has access to accurate information and intelligent discussion of public policy. That means, I am convinced, national newspapers of high quality; it is one of the greatest educational priorities. American hybris is in part the consequence of a mindless, provincial press that has abandoned its task of promoting the general enlightenment. Yet we possess everything necessary: the technology, the journalistic skill, even, I believe, the readership. If the First Church of Christ Scientist can create a national newspaper, is it beyond the power of a consortium of eight or nine major private universities to do the same? Money matters as always, but the real obstacle is simple inadvertence and bad habit. Journalism is one thing, we say, and education another. But in a mass society, in a world of explosive illiteracy, the two are inextricably fused.

An independent drug-testing center. Senator Gaylord Nelson recently proposed the establishment, outside the government, of a center for the testing of drugs. He had in mind, I suppose, the near disaster a few years ago when a lone civil servant, Frances Kelsey, barely prevented the national distribution of thalidomide. So long as drug controls, and standards generally, are housed in the government, the public interest will be vulnerable to commercial pressures. Far better, it would seem, to create independent centers and a new professional ethos. What better place than a university of the public interest? What better training for future pharmacists?

The government, I am suggesting, is not the ideal context for many vital operations, and these could and should be assigned to other institutions. The effect of assigning them to the university is to make the university a direct defender of the public interest, as it now is not. But the assignment also makes sense; it is something that universities have an obvious capacity to perform. And this tells us something about what they might become, if that capacity were licensed and then widened.

All these are simply typical projects by which a university of the public interest might be enabled and its educational mission defined. Other possibilities readily occur. I have long been convinced, for instance, that universities should create their own learning corporation, in order to appear in the market with the threat of real quality. Educational technology has been invaded by very large corporate interests, and educators must act if they are to retain control of their own curricula and policies. Again, a university of the public interest would have an obvious responsibility to defend the economic and cultural interests of those minorities too weak or disadvantaged to help themselves; I think, for instance, of the Indians and their struggle against the arrogance of their custodians, their need for legal help. And the suggestion of Harry Ashmore, that universities should carry out a systematic and running criticism of the mass media and their performance, is important; what is more, it is something that universities could do now, without radical dislocation. I wonder also whether our conduct of cultural relations with other countries would not be better performed by a university consortium than by USIA. It is not wholly clear to me that culture should be reviewed as an arm of journalism or propaganda, and I wonder why American culture should not be permitted to look as heterodox as it is. And we need institutes for policy study, and for criticism and study of technological change. And so on.

I ASSUME the public interest will be served by such projects. The educational benefits, I would argue, are extraordinary. First, a context in which knowledge, applied in a spirit of service, could be made moral; in which skills and values could be enlarged by meaningful use. Second, an overriding mission in terms of which men might pool specialized skills, simply because there is no other way of carrying out their task; in short, a context in which interdisciplinary work would occur naturally, as it now does not. Third, the community such collaboration might create the community we do not have. Fourth, the possibility of recruiting generous human energies which now have almost nowhere to go - energies which, turned rancid and frustrated, make education impossible. Finally, the hope of restoring the authority of intelligence and reason by their visible pertinence to the task in hand.

These are all proposals whose aim is to make of the university a third force in American life - a force that is neither government nor industry, but rather a new form of spiritual institution. I offer no apology for the phrase. No great society has yet managed to survive without powerful spiritual institutions, whether subversive or established. They are made up of men who, in Chapman's words, sound a certain note: "They hold a tuning-fork and sound A, and everybody knows it really is A, though the time-honored pitch is G flat. The community cannot get that A out of its head. Nothing can prevent an upward tendency in the popular tone so long as the real A is kept sounding." It was the intent of the founding fathers that family and church should speak for the spirit in American life. They could not have foreseen the dreadful eclipse of both those institutions, nor the ominous concentrations of wealth - and hence of political power — in recent years. To some degree the spirit survived in the courts and the foundations; but Congress has now emasculated the foundations, and the courts have been gutted. The spirit is not in good health or odor. Many think it a myth. And with good reason. Unselfishness in American life is unincorporated; it has no coherent party or program, no normalized institutional home. And the absence is as tangible as the absence of God. Indeed, the demands now being made of the university are, I believe, as unappeasable as they are because they are unrecognized demands of the spirit. The university is being asked to act as a spiritual institution. But because nobody believes in spiritual institutions, the demands come disguised as intransigent political demands.

The critical problem is to make the university a potent institution of the spirit. Only in this way will it come to have genuine political influence, the kind of influence needed, in a mass society, to affect the quality of life. The difficulty is transcending old habits. So long as the university community believes its true constituency is the classroom it is doomed to the custody of increasingly dissatisfied and ungrateful students. Our universities now have a mandate to educate all. But we cannot confine all the young to institutions. And the consequence is that the classroom becomes the country. But you can't educate a country by classroom techniques, by formal instruction. You educate rather as an artist does, by what you say and do, by rational persuasion; or like a pre-Socratic, by embodiment and example. But the embodiment is institutional as well as personal, since it is potency we want. In this view the university becomes an active designer of the culture, a shaping rather than a passive force; and its curriculum and staff derive from its mission. It educates because it represents the spirit in a dirty world. It shows, as an institution, what men might be if they were free to be what they wanted. It embodies conscience, because it trains conscientious professionals; compassion, because only compassion could explain its strange behavior, and so on. Its potency derives not only from the spirit, but from the institutional elan, the "Jesuit" energy and the modernity of its methods.

A university of the public interest is not, I believe, a visionary project. It is already emerging around us, the shape of the future institutions looming unmistakably behind the confusion and frustration and anger. Signs of its incipience are everywhere; they are particularly hopeful here at Dartmouth. There is hardly a reform I have suggested that is not an extension or consolidation of isolated, often abortive but remarkably persistent efforts at reform everywhere.

These efforts take a common direction, and it is crucial to name it. Otherwise we are apt to miss what is positive and hopeful and see only anarchy and trouble. The point is this: we are on the point, now, of creating here in America a great new social institution, a wholly new form of university, adapted to the requirements of a new mass society and a new human condition.

LET me close with another Indian. The speaker is Chief Seattle, and the occasion is his response to the whites who demanded that he and his tribe go to the reservation. It is one of the most compassionate and moving statements I know - all radiant sophrosyne, a charity that understands even the whites. Seattle knows hybris for what it is, but he knows it is human too. To us, now, Seattle speaks as part of that great community of "others" which all education hopes to knit into our lives, until it becomes conduct and second nature. It is a great man who speaks, and behind him a great culture:

"Our great father Washington sends us word that he will protect us if we do what he wants. His brave soldiers will be a strong wall for my people, and his great warships will fill our harbors. Then he will be our father and we will be his children.

"But can that ever be? Your God loves your people and hates mine. He puts his strong arm around the white man and leads him by the hand, as a father leads his little boy. He has abandoned his red children. He makes your people stronger every day. Soon they will flood all the land. But my people are an ebb-tide, we will never return. No, the white man's God cannot love his red children or he would protect them. Now we are orphans. There is no one to help us.

"So how can we be brothers? How can your father be our father, and make us prosper and send us dreams of future greatness? Your God is prejudiced. He came to the white man. We never saw him, never even heard his voice. He gave the white man laws, but he had no word for his red children whose numbers once filled this land as the stars filled the sky.

"No, we are two separate races, and we must stay separate. There is little in common between us.

"To us the ashes of our fathers are sacred. Their graves are holy ground. But you are wanderers, you leave your fathers' graves behind you, and you do not care.

"Your religion was written on tablets of stone by the iron finger of an angry God, so you would not forget it. The red man could never understand it or remember it. Our religion is the ways of our forefathers, the dreams of our old men, sent them by the Great Spirit, and the visions of our sachems. And it is written in the hearts of 'our people. ...

"A few more moons, a few more winters, and none of the children of the great tribes that once lived in this wide earth or that roam now in small bands in the woods will be left to mourn the graves of a people once as powerful and as hopeful as yours.

"But why should I mourn the passing of my people? Tribes are made of men, nothing more. Men come and go, like the waves of the sea. A tear, a prayer to the Great Spirit, a dirge, and they are gone from our longing eyes forever. Even the white man, whose God walked and talked with him as friend to friend, cannot be exempt from the common destiny.

"We may be brothers after all. We shall see."

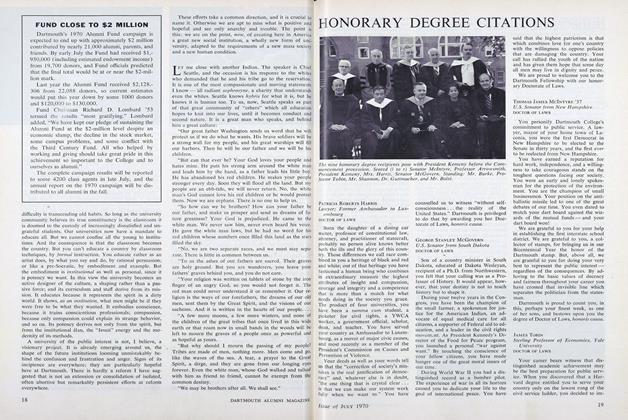

Dr. Arrowsmith delivering Commencement Address.

At their garden reception Friday evening President Kemeny (left) and Mrs. Kemeny (right) greet Commencement guests.

At their garden reception Friday evening President Kemeny (left) and Mrs. Kemeny (right) greet Commencement guests.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Undying

July 1970 By SHERMAN ADAMS '20 -

Feature

FeatureDero A. Saunders '35 Elected President of Alumni Council

July 1970 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1970 -

Feature

FeatureReunions, 1970 Style

July 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureFour Alumni Awards

July 1970 -

Feature

FeatureThe Senior Valedictory

July 1970 By CRAIG JOYCE '70

Features

-

Feature

FeatureLiveliest Point of the Summer

October 1954 -

Feature

FeatureOur Way in the World: A Conversation with John Dickey

January 1976 -

Feature

FeatureReligion and the Biological Revolution

JANUARY 1973 By CHARLES H. STINSON, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF RELIGION -

Feature

FeatureConquest of the Antarctic

June 1957 By DAVID C. NUTT '41 -

Feature

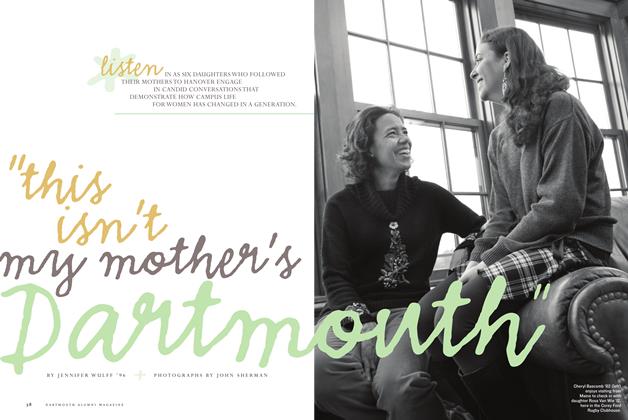

Feature“This isn’t My Mother’s Dartmouth”

Sept/Oct 2010 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureTwo Women, Once Alive

October 1993 By Tig Tillinghast '93