I AM heartened that all of us have gathered here to take part in Dartmouth's 200th commencement. Many of our divisions this spring were quite deep. But today we demonstrate that affection for family and loyalty to this institution still unite us.

THE CURRENT DILEMMA

This morning I intend to talk about the role of American universities as sources of ideas and criticism in our society. Certainly none of us can ignore the questions raised by six weeks of turmoil on college campuses across the country. For, while Dartmouth's activities remained peaceful throughout, an overwhelming majority here did commit themselves to the protest movement. Now that the academic year is over, we have the time - and indeed, the responsibility - to reflect on the implications of this commitment.

Essentially, the ideal of the university as Ivory Tower has undergone - and, I think, not fully withstood - a severe assault. Many of those who make up the university community in America no longer accept that ideal, insofar as it requires them to refrain from direct participation in public affairs. They are no longer content to be scholars in their working hours and citizens in their spare time, as if the two roles were completely and properly separable.

I would not have university people altogether discard their attachment to quiet scholarship. To demand that the university's every activity be "contemporary" and engage is to forget other enduring values of liberal learning. As Charles Frankel of Columbia has said in his book, Education and the Barricades, helping a man to learn detachment, to recognize the limits and ambiguities of his ideals, is a purpose of education. To take a man out of his own time and place, out of a narrow and demeaning preoccupation with himself, is another. And to show him the uses of the useless, of those absorbing irrelevancies which somehow enlarge the mind and intensify the consciousness, is a third purpose.

Fortunately for all of us, the developments of this spring hardly portend doom for the purposes of the university outlined by Professor Frankel. At Dartmouth and at most of the other institutions I know, those who joined the protest are conscious of the dangers involved in political activism. They do appreciate that without the continuing discipline of normal studies, students could not develop or faculty members maintain those powers of insight and persuasion which they so recently focused on the problems of Southeast Asia.

The question, then, is not whether universities will remain as centers of higher learning, nor whether they will serve as havens for a certain amount of political participation. With prudence and good sense on the part of those who compose them, the universities can do both.

The real question is this: Can the academic community justify its exercise of an active concern for American society? My own answer is Yes, and the reasons lie in my understanding of the nation's present difficulties.

RESPONSIBILITY TO SOCIETY

The first point is obvious. Having taken the lead in creating an age of high technology, this country has now become a primary victim of the resulting changes. Members of the university community have recognized that unguided material change will not automatically produce a healthful, a pleasant, or a just society. We have seen that technology itself can make the physical world ugly and almost unlivable. Not only that. We fear that uncritical devotion to the machine culture will turn man's social and psychological environment into a forbidding wasteland, too.

Clearly this society's ability to overcome specific problems such as foul air and dehumanizing cities, perhaps ultimately its ability to survive, depends on the intelligent ordering of change. All of our ideas and institutions should be carefully and continually evaluated. All must be proven suitable to present-day needs; if they fail the test, they must be updated or replaced.

I believe that the task of providing an infusion of critical and creative ideas must fall to the nation's universities. After all, business corporations and government bureaucracies do not generally provide people with the time and freedom required to reflect on the long-range effects of change in America. The universities do.

The academic community has the privilege to explore the laws of nature and the nature of man. To that privilege, however, attaches a certain responsibility. In an age when knowledge is quite literally power, information and skills originating in the universities find applications of tremendous significance beyond the ivied walls. Pure scholarship ceases to be pure when its fruits can be used, however indirectly, to "sell" the voters a well-packaged but worthless candidate, to destroy a river system's ecological balance by thermal pollution, or to defoliate a jungle forest more efficiently. In such instances, academics cannot escape the duty to speak up, whether or not initially most people want to listen.

If I may summarize my argument thus far, America needs to develop effective responses to the social and political problems engendered by rapid industrial and technical advance. University people, who create much of the knowledge usable today, should also offer their informed opinions - if necessary, their energies — to ensure its wise application.

A MATTER OF WILL

This in itself will be of little value unless the university community succeeds in a second and equally important effort, that of helping society to recover its openness to whatever fresh ideas may be proposed.

This is a problem of considerable moment in June 1970, when an inflexible hostility to social innovation pervades the mood of many Americans. Public opinion has become decidedly intolerant of unorthodox viewpoints and modes of action. Some political leaders condemn all who have disturbed the hallowed calm of our academic monasteries as "troublemakers," or more glibly, as "choleric young intellectuals and tired, embittered elders." Statements of that sort indicate, and in fact they promote, an atmosphere in which the pioneer and the dissenter alike will be increasingly mistrusted, discouraged, even repressed.

In this situation, the university community must demonstrate that social criticism can be deeply responsible and true to the nation's best interests.

No matter what others may do, we on the campuses should maintain our own commitment to civilized behavior and discourse. We should put our message as simply, as cogently as possible.

America Has not achieved its promise and potential. With all its wealth and technology, this nation has the power - if it can summon the will — to make the reality of its life more fully reflect the decency of its ideals. Surely we all know that malnutrition and bitter poverty need not persist in Appalachia or in the Mississippi Delta. Surely we agree that discrimination against minority groups - ethnic or racial - need not continue anywhere. Such inequities remain not really for lack of means to correct them, but because of our society's moral and spiritual default. If American universities can sufficiently inform public opinion and excite public concern, then solutions may be possible. That is our hope and our calling.

THE SCHOLAR-CITIZEN

I said at the outset that the ideal of the university as Ivory Tower has been somewhat modified recently. We should still value the Ivory Tower as a vantage point from which the scholar can look out over the world as it is and think on what might yet be. But to do anything constructive about what he sees and imagines, the scholar must have a stairway from his study down to ground level. And that stairway should be well used.

Some 63 years ago the Reverend William Jewett Tucker, ninth President of Dartmouth College, spoke his own thoughts on the task of the scholar-citizen:

"I express the hope that the mind of this College will always be hospitable to the claims of citizenship. I express the hope that your minds may be open to these claims here and now. ... You have no right to expect to live in freedom and safety upon the devotion and sacrifice of other men. Whatever you may accomplish, or may fail to accomplish in the furtherance of your personal aims and ambitions, may you know in the final reckoning with yourselves, that you have given something of your best thought and purpose to the advancement and perpetuity of the nation."

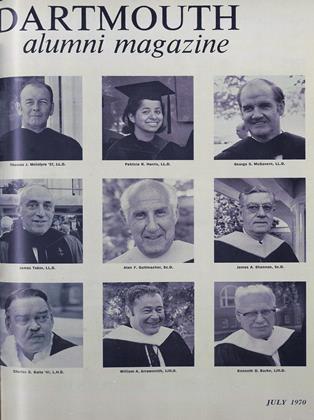

Valedictorian Craig Joyce '70

Mr. Joyce, whose home is in Tempe,Arizona, ranked first academically in hisout of a possible perfect 5.0. He was grad-class, with a four-year average of 4.923uated with highest distinction in historyand will spend the next two years at BalliolCollege, Oxford, under a Keasbey Memorial Foundation Fellowship. He was alsothe recipient of a James B. Reynolds Scholarship from Dartmouth and of a WoodrowWilson National Fellowship.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHYBRIS AND SOPHROSYNE

July 1970 By WILLIAM AYRES ARROW SMITH, LITT.D. '70 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Undying

July 1970 By SHERMAN ADAMS '20 -

Feature

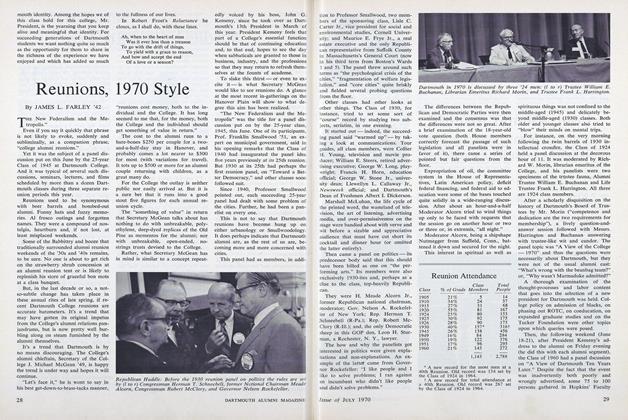

FeatureDero A. Saunders '35 Elected President of Alumni Council

July 1970 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1970 -

Feature

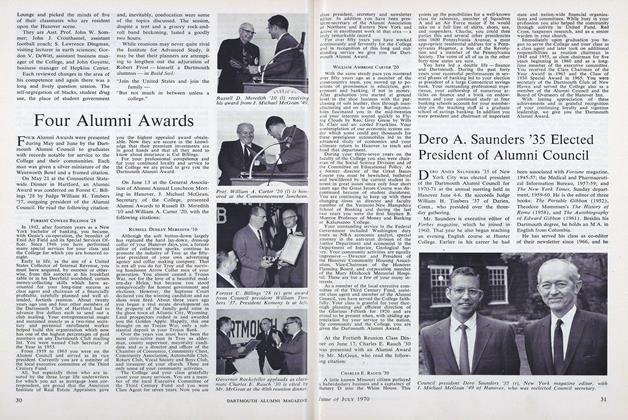

FeatureReunions, 1970 Style

July 1970 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

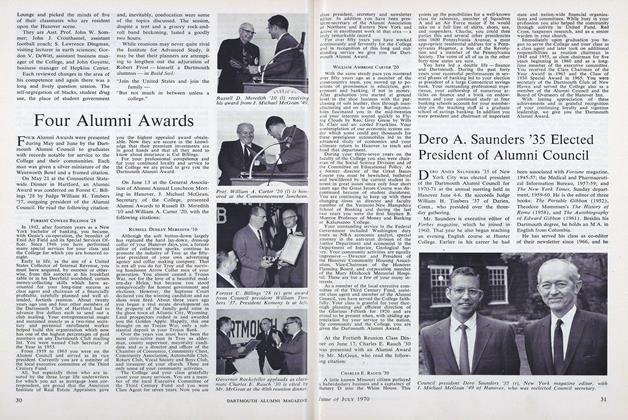

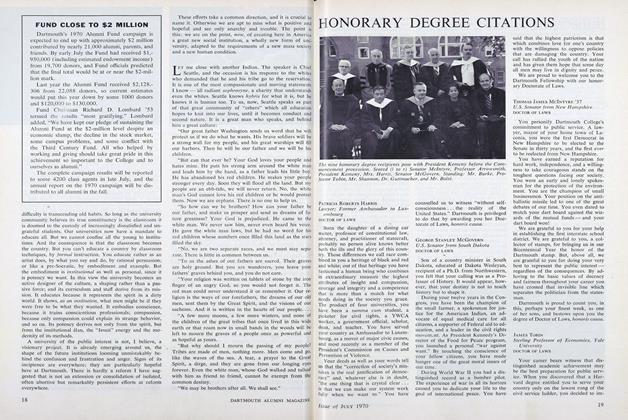

FeatureFour Alumni Awards

July 1970

Features

-

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Hold Annual Meeting

DECEMBER 1972 -

Cover Story

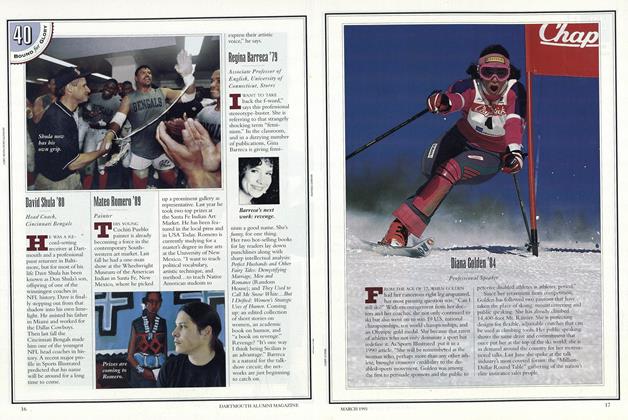

Cover StoryRegina Barreca '79

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureZoology

MAY | JUNE 2014 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

Feature1953's Triple Alliance

November 1968 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

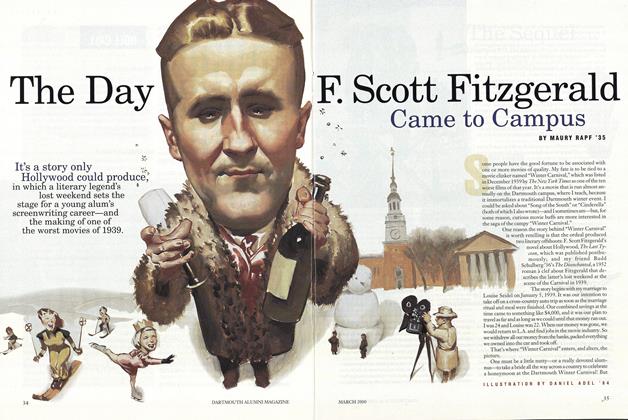

FeatureThe Day F. Scott Fitzgerald Came to Campus

MARCH 2000 By MAURY RAPF ’35 -

Feature

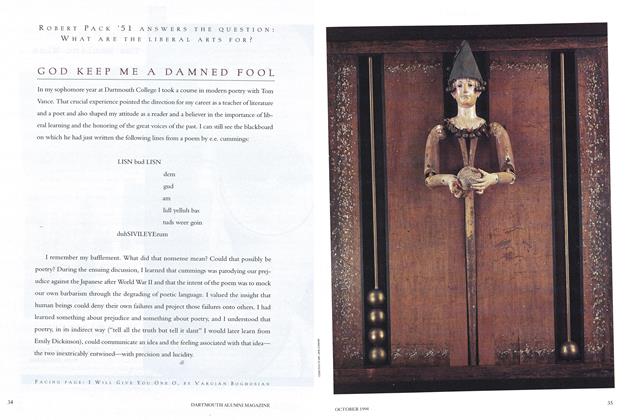

FeatureGOD KEEP ME A DAMNED FOOL

OCTOBER 1994 By Varujan Boghosian