College Plans a New"Sabbatical" Program ofEducation for Adults

In his inaugural address of March 1, 1970, and on many subsequent occasions, President Kemeny voiced the belief that it is increasingly essential for the adult in the modern world to keep working at his education. To bring to fruition the hope that Dartmouth can take the lead in offering men and women the sort of on-campus program that would meet this need, he appointed two task forces last fall to study the feasibility and possible educational content of the idea.

The program envisaged goes well beyond the scope and duration of a continuing education program such as Alumni College, which will still have its definite place. President Kemeny speaks of it as a "sabbatical" and has business executives and professional people particularly in mind as adults who would benefit from a return to formal education within the university.

On the basis of the first report from the President's task forces, the Dartmouth Trustees at their Hanover meeting last month endorsed the idea of establishing The Dartmouth Institute, a four-week, summer program of liberal arts education for adults. The task forces will continue their detailed surveys of feasibility, financing, and educational program, and will determine whether the Institute might be launched in the summer of 1972.

The recommendation of the task forces that The Dartmouth Institute have a Director was also approved. To fill this post, President Kemeny announced that he had chosen Gilbert R. Tanis '38, currently Executive Officer of the College. Mr. Tanis, whose new title will be Director of Continuing Education, will continue to be President Kemeny's chief assistant for the next eight months while taking on his new responsibilities, and will then become full-time Director of Continuing Education on January 1, 1972.

The two study groups that presented the report to the President are headed by James F. Cusick, Professor of Economics Emeritus and first faculty director of Alumni College, who is chairman of the task force on educational content; and J. Michael McGean '49, Secretary of the College and first administrative director of Alumni College, who is chairman of the task force on feasibility.

The initial report of the two committees included a variety of attendance and cost projections, as well as a possible three-course curriculum dealing with The Ecological Crisis, The New Morality, and The Role of the Computer Today and Tomorrow. These portions of the report are tentative and have not been made public, but the section dealing with the general character and purposes of The Dartmouth Institute serves to give a clearer idea of this new form of continuing education and is printed here in full:

Purposes

The Dartmouth Institute is an educational program for adults for a period of four weeks. It is a "liberal arts" program with the following purposes:

(1) To help men and women remain contemporary in their thinking and decision-making by enlarging their understanding of the rapidly changing social, economic, and political environment;

(2) To increase understanding of the impact of change on values of individuals and organizations;

(3) To provide an appreciation of the possible dimension of human growth.

The pressures of modern business and professional life coupled with the increase in specialized information make it difficult to have a continuing concern for the world of ideas and values. Yet, there is a growing awareness that the only counter to the ills of specialization is to be found in the liberal arts.

In the future, the time devoted to education must be increased. Education cannot be thought of as something which is co-terminous with formal schooling. It must be thought of as a continuing process which goes on throughout the life of the individual. It will vary with the interests of individuals, but the nature of our problems makes a compelling case for a continuing program of self-development. Moreover, it is increasingly apparent that the continuing education of its executives must be thought of as a responsibility and necessary investment of a business firm or professional organization which hopes to maintain itself and thrive in this rapidly changing world.

In previous generations, the rate of change was so slow that the world outlook which a man had when he graduated from college could still be substantially valid when he reached fifty. This is no longer so, and to be contemporary with the changing times a man must adapt, and adapt again. Otherwise, a man of fifty may find himself an immigrant in a new world; a displaced person in a society in which he has ceased to feel at home, and in which he can no longer function effectively.

In this same vein, Bentley Glass, president of the American Academy Science, speaks of "educational obsolescence" and declares: "Programs of continuing education for all professional people must become mandatory, and the educational effort and expenditures must be expanded by at least a third to permit adequate retraining and reeducation.

In this age of rapid change, those responsible for policy must have concern for two distinct aspects of society:

(1) The "operational"—the day-to-day visible forms of activity such as business, politics, and the functioning of social institutions, the activities of manufacturing, labor unions, legislative bodies, party politics, and the infinite variety of organized activities which give form to current society.

(2) The "ideational"—the basic attitudes, beliefs, and values to which common allegiance is given. Such values and their symbols serve to hold the disparate elements of society in some form of community. They make up the invisible constitution which is the foundation of a stable society. These basic values may or may not be expressed or openly discussed. They are, in the words of Justice Holmes, the "inarticulate major premises" which serve as the source of ultimate authority for innumerable lesser judgments and decisions. They are the unwritten constitution which gives authority to written constitutions, laws, and social institutions.

To place all emphasis on the "operational" with its short-run views and limited objectives is myopic. We need not only the microscopic study of the organization and its management problems, but the telescopic study of the organization's environment—historical, economic, social, political, and ethical.

Business and the professions must develop leaders who have this dual capacity and concern. They must use both the microscope and the telescope. The essence of good management is the good man.

Moreover, the welfare of one business enterprise can no longer be thought of as an isolated problem. Each firm is a part of a complex economic and ecological system, and the decisions of a firm affect these systems, while changes in the economic or political order affect the individual firm.

The businessman has a great stake in the nature of the value system (or scale of national priorities) from which Public policy and administration flow. His business is likely to be affected in some fashion for good or ill. He should not be, nor will he be, a passive factor in the midst of such change. He will continue to play a significant role in the formulation of public policy. In order to make this role a constructive one in the new age, he must realize that many of the basic forces affecting the business world will flow from the changing values of the community. He must devote an increasing portion of his time and energy to what for the typical businessman will be a new world, the world of ideas and values.

There is another reason why business and professional people must have a greater sensitivity to values. Modern youth is a cause of increasing concern to the adult world. The so-called youth culture is developing a set of attitudes and a code of values which is critical of many established institutions including not only government but also the organization, conduct and values of the business community. The business community may find it increasingly difficult to induce young people to play a positive role in business enterprise unless some degree of mutual respect and appreciation is attained.

The sheer productivity of capitalism has produced a level of material well-being which has furnished a favorable environment for the assertion of other values such as increased altruism, development of human potential, artistic and creative expression, and increased sensitivity to others.

Such emerging values on the part of increasing numbers, especially on the part of youth, pose new problems for business leadership. Problems of management become increasingly complex and subtle as the manager is called upon to deal with people within the framework of a changing value system. His task calls for an awareness of and an effort to appreciate fundamental changes which are "in the air."

Effective management in this era of change calls for a manager who is sensitive to the "new humanity" and responds to it. There is no better method of encouraging a reexamination of the shifting values of society and of the self than an exposure to the humanist tradition embodying as it does most profound expressions of scientific, aesthetic, philosophic, and religious insights.

Gilbert R. Tanis '38 fills the new postof Director of Continuing Education.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureNefertiti, Akhenaten, and Ray Winfield Smith '18

May 1971 By John R. Scotford Jr. '38 -

Feature

FeatureTrustees Vote to Consider Associated School for Women

May 1971 -

Article

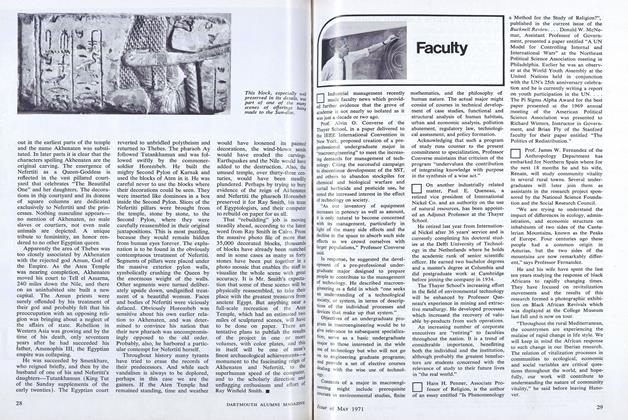

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

May 1971 By JOEL ZYLBERBERG '72 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

May 1971 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleHanover's Famous May "Murder"

May 1971 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1935

May 1971 By RICHARD K. MONTGOMERY, GEORGE PRICE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Lifetime of Theater

JANUARY 1968 -

Feature

FeatureGOOD HAIR

MAY | JUNE 2014 By Ana Sofia De Brito ’12 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO WIN AT LUGING

Sept/Oct 2001 By CAMERON MYLER '92 -

Feature

FeatureThe Image of the Educated Man

July 1960 By HARRISON CASE DUNNING '60 -

Cover Story

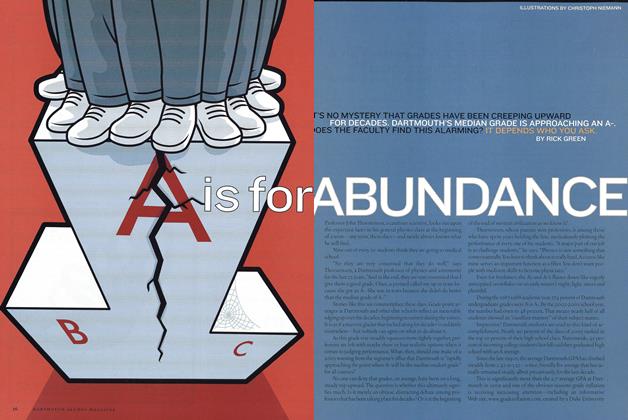

Cover StoryA is for Abundance

Mar/Apr 2004 By RICK GREEN -

Feature

Feature'A need for someone who holds my views'

November 1979 By William M. Hill