ONE MORNING SOMETIME IN 1951 I entered the federal courthouse on Foley Square in lower Manhattan to report for jury duty One of the elevator doors slid open and a man I recognized as William Remington emerged. I knew him as a fellow alumnus who had started in my class, dropped out for a year, and then returned to Hanover to live down the hall from me on the third floor of Crosby House.

Our eyes met, then slid past. I wanted to greet RemingtSn and say I was pleased that he had been cleared by the Loyalty Review Board. But I hesitated. Why was he back in the courthouse? When I turned he was gone. Should I try to catch up to him? Did he recognize me? Ever since then I have wondered if he said to himself, "There goes another Dartmouth bastard pretending he doesn't know me."

The jury I was on was trying ten defendants on a drug conspiracy charge. They were being defended by four lawyers, and implicated by a dozen witnesses who had been found guilty and were cooperating breathlessly in an effort to get reduced sentences. The trial lasted more than two weeks, and I watched for Remington as I came and went. I had rehearsed my approach to him until I was satisfied that the note it would strike would be one of supportive, unintrusive, optimistic concern.

But I never saw him again.

By 1956, when I returned to Hanover to work for the College, Bill Remington had been dead for two years, murdered by three fellow inmates in the Federal Penitentiary in Louisburg, Pennsylvania.

Crosby House, the dorm, had become Crosby Hall, remodeled for administrative offices. And I was right back where I started at Dartmouth. As an exercise in nostalgia I dropped into the College housing office to get a list of names of all who lived there from 1934 to '38. They wanted to be helpful but explained that their Crosby files and those of Hitchcock and Wheeler were in disarray. The FBI had been up a few years before, trying to find out who lived near Remington during his days in Hanover.

Remington again.

Even though we had shared the bathroom with 21 others in Crosby, I had no specific memories of any conversation with him or of taking the same courses. So in an unorganized way I kept watching for his tracks. I went through his folder in the Baker Library archives and talked to others who were his contemporaries.

Then in February of 1986 Ken Cramer, the archivist in Baker, told me that a professor at the University of Delaware named Gary May had been making enquiries about Remington for a book. And thus began an association which developed into a warm friendship. May had originally planned to spend two or three years on the project. I have asked help from dozens of alumni, professors, and administrators who remember him.

May's book, Un-American Activities; The Trials ofWilliam Remington, was published last summer. But this is not a review. I am not a disinterested critic. There are many things about Bill Remington that I admire, and others I deplore. I also admire Gary May and his prodigious task.

Nor is this a synopsis. I do not want to dilute May's saga. It is a trip well worth taking not just for the scenery but for the cast of characters. It is full of bad guys, a few saints, and many innocent bystanders—such as Remington's family, who suffered grieviously. Very few people or institutions come out unblemished. Even atter Remington was murdered, the FBI and the Federal Bureau of Prisons were covering up, pointing elsewhere, and fabricating motives. The reader not only follows Bill Remington's descent to Hell but hears the voices of those who tried to hold him back and those who pushed him to his doom.

Just as interesting to readers of this magazine, the index lists 455 people whose lives touched Remington; 56 of them are Dartmouth people.

Just as tramp steamers attract barnacles, controversial characters gather false myths. A classmate remarked to me, "Oh yes, Bill Remington! He was the flaming red who wanted the Communist hammer and sickle flown at the ski jump at Winter Carnival." I checked this out with Dave Bradley '38. "No, no! What happened was the Dartmouth Olympic skiers got to know the European universities skiers at the Garmisch-Partenkirchen Games in 1936. The following year the Swiss universities team came and in 1938 the German universities ski team came. They brought their swastika flag and it was flown along with the Canadian and U.S. flags. I am sure others found that distasteful, but Remington was the one who objected most strenuously and publicly."

Which comprises yet another footnote,

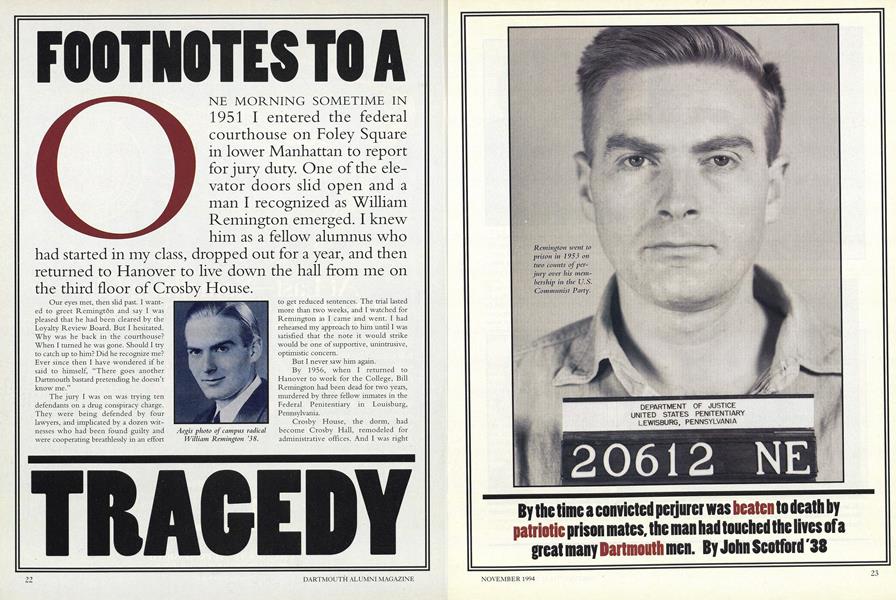

Aegis photo of campus radicalWilliam Remington '38.

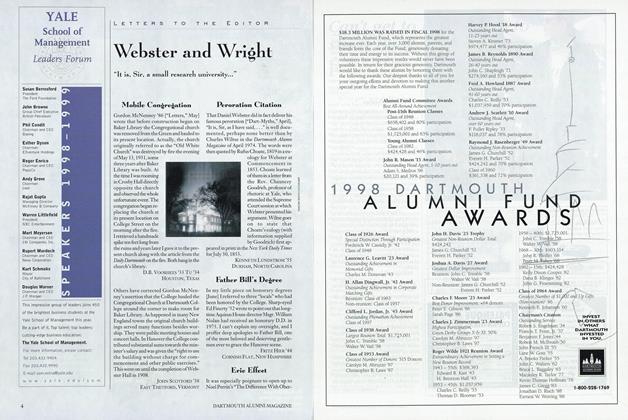

Remington went toprison in 1953 ontwo counts of perjury over his membership in the U.S.Communist Party.

Remington's father—whom his son had called a "capitalist stooge"—accompanied him to his trial in 1951. Hehad his conviction reversed, only to be re-indicted.

Remington was a rising government economistbefore he was accused in 1948 of being a spy. Hetestified before a Senate committee; in 1951 ex-wife Ann Moos Remington testified against him.

Remington with son Bruce 9 anddaughter Galeyn 7. This photo wastaken the day the U.S. Court ofAppeals reversed his first convictionfor perjury. The good times were notto last; U.S. attorney Miles Lane '28was to prosecute him in 1953 forperjury during the first trial.

Car thief Robert Parker was McCoy'sroommate. He robbed Remington beforethe murder and witnessed the crime.

Lewis Cagle Jr. was a 17-year-oldjuvenile delinquent who used a brick ina sock to hit Remington repeatedly.

Virginia mountaineer George McCoyhad an I.Q. of 61 and a hatred ofpinkos. He finished Remington off.

By the time a convicted perjurer was beaten to death bypatriotic prison mates, the man had touched the lives of agreat many Dartmouth men.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

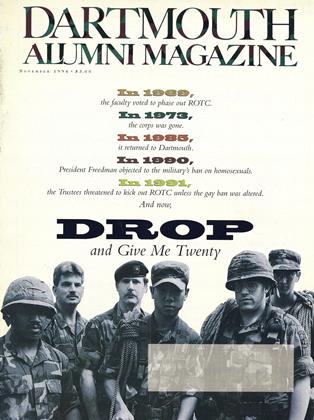

Cover StoryYou Thougnt Rotc was Dead?

November 1994 By Frederic J. Frommer -

Feature

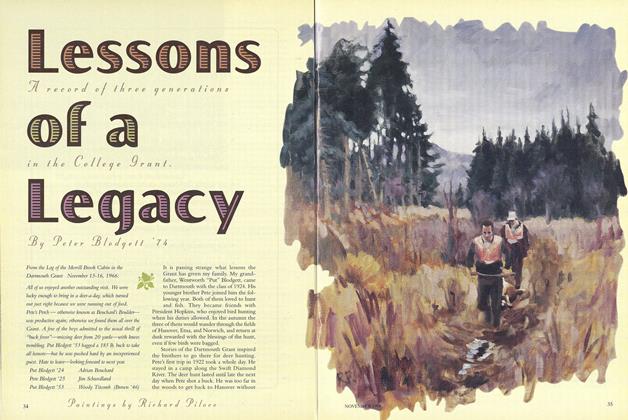

FeatureLessons of a Legacy

November 1994 By Peter Blodgett '74 -

Feature

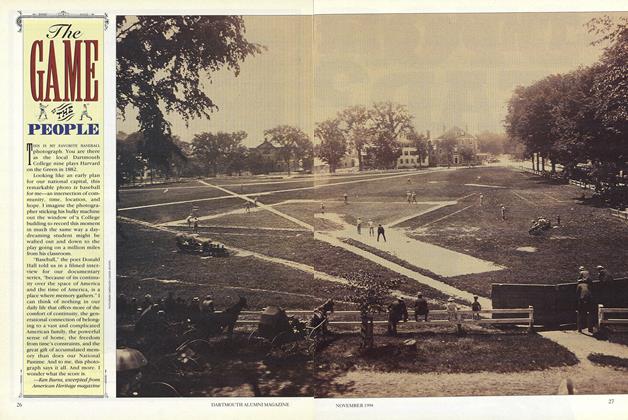

FeatureTHE GAME PEOPLE

November 1994 By Ken Burns -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

November 1994 By Daniel Zenkel -

Article

ArticleEssayists and Solitude

November 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1994 By "E. Wheelock"

John Scotford '38

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1966 -

Feature

FeatureCALLAHAN

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Feature

FeatureMovie Producer

DECEMBER 1969 By HAROLD BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureFrom "a few curious Elephants Bones" to Picasso

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Jacquelynn Baas -

Feature

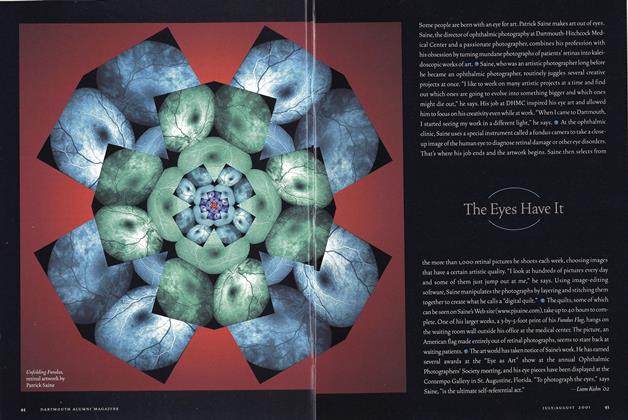

FeatureThe Eyes Have It

July/August 2001 By Liam Kuhn ’02