We celebrate the 100th anniversary of Thayer School at a time when it is fashionable to blame science and technology for all the ills of the world. Yet it is my conviction that the fundamental problem is our total inability to manage science and technology and to bring them to bear on the problems of society.

I would like to discuss this problem in terms of a concrete example, and I have chosen our national transportation system. My first observation is that we do not have a national transportation system. We have a historical accident compounded by shortsightedness, greed, and political manipulation.

We once had a great railroad network, and today at a time when many nations have rejuvenated railroad systems that serve as a matter of national pride, our passenger system is essentially dead. It was killed through greed. It was killed by the taking of profits without ploughing them back into maintenance and improvements. It was killed through gross mismanagement. It was killed through unions that became so greedy and shortsighted that in the long run they will put most of their members out of work. It was killed by a national policy that subsidized all the competitors of the railroads and neglected the railroads themselves.

Next we built an air transportation system, and in the beginning we saw great improvement. It is certainly wonderful to be able to fly coast to coast in five hours. For a while we seemed to have a policy of building up an air transportation system to serve all communities, including this one. But then profits fell; we lost interest in subsidizing air transportation, and so we found more and more communities cut off from the national system.

Through these years the growth in the number of airplanes brought about new problems. We created congestion in the air which should have been completely predictable. We created sonic booms making life difficult in many parts of the country. We created the problem of moving thousands of people through highly congested cities to the terminals that service the airplanes. And, when all these problems confronted us, what great national plan was proposed to solve them? It was proposed that we build a supersonic transport plane which would produce greater sonic booms, which would mean moving more people through highly congested cities, and which would have a negligible effect on the problems that really worry most air travelers.

Take a typical trip by airplane from Boston to New York. From the time when you leave your home in a suburb of Boston, you fight through the traffic to get to the airport. You wait until you can get on the plane. You then have a short and usually pleasant flight to New York. You then wait for your baggage, try to get a cab, and fight even worse traffic getting into Manhattan. Of all of these, the only part that works well is the actual flight; and therefore it seems to me that if we are going to improve the air transportation system, one should work on those problems that are pressing on all people and not on a major new project that is going to be of benefit to only a handful of people.

We also built a great highway system, and this too had many benefits. Indeed we are fortunate in this part of the country; it is safer and less frustrating to drive on our great interstate routes than on the roads that existed a decade ago. I'm sure that students find the trip to Smith both faster and more enjoyable as a result of it. And in addition, in Vermont and New Hampshire you can enjoy the scenic beauty that accompanies these interstate roads. And yet these highways created problems of their own. With some one hundred million cars on the road, the problem of pollution in the nation is threatening the survival of mankind. At the same time we are using at an alarming rate natural resources of the world which can never be replenished. And while it is wonderful to have interstate roads when you live in Hanover, New Hampshire, they are threatening to bring death to the inner parts of several of our oldest and best known cities.

We have reached a stage where the main means of transportation (because we don't have a public system) is the private car. If you look at two examples of the effects of millions of private cars on cities, you can see the problems that confront us. Let me first take Los Angeles. It is a city that boasts of the greatest freeways—engineering miracles on which you can speed at 70 miles an hour right through the center of the city. I remember our experience the last time I was in Los Angeles. We went bumper to bumper on one of these 70-mile-an-hour roads at a speed somewhat slower than that which would have been possible with a horse-drawn carriage several generations ago. At the same time I witnessed thousands of cars fuming into the already smog-filled air. I saw the tremendous waste in resources. If my estimates were right, we averaged one and a half people per car, all going in the same direction for a stretch of twenty miles. I couldn't help thinking that there must be some rational way for providing a mass transportation system that would replace this completely haphazard, accidental method of transporting the majority of our people.

In New York the problem is much worse. I went to high school in New York City and it is a city I once loved. But since that time everything that man could do to ruin it has been done. It once had, believe it or not, a great subway system. It once had good bus service. It once had commuter railroads that people enjoyed riding. Instead of that, Manhattan today is the greatest traffic jam in the nation, with its streets permanently torn up for improvements.

We seem to cater, in our planning of city transportation, to the desires and the whims of the rich and the selfish. We ignore the needs of the poor and those who do not have a sufficient voice in the affairs of our nation; and yet justice is done in the end, because while we make life almost impossible for the poor, in the not-so-long run we succeed in making life impossible for the rich and the selfish as well.

Let me mention one example of the way cities make major decisions. I happened to be in New York at the time of the great controversy as to whether to finance subway construction by means of raising the fare on subways or raising the toll to get into the city by car. This went on for a very long time. It would seem to any impartial observer that the solution was clear. If you raise the fare on the subway, then fewer people will take the subway, and it will be harder to maintain it and justify it, and you are going to encourage more cars to come into the city, to compound an already almost hopeless problem. If, instead, you raised the tolls on bridges and tunnels, you might encourage more people to take an interest in the public transportation system, and you might remove a few thousand of the cars that now pollute and jam up the city. You might even consider something drastic such as a $5 or $10 fee to get into Manhattan, or possibly a prohibition of all private cars in the central city.

I don't have to tell you what the outcome was. Subway fares were raised.*

When one looks at city planning, one sees cities that still have a hope, except for certain areas that are traditional bottlenecks where traffic jams up. And then you hear that three more great skyscrapers are built—and where are skyscrapers built? Right in the middle of the worst traffic jam.

The cumulative effect of all this lack of planning and shortsightedness, I claim, goes way beyond simply the discomfort that has been given so much publicity. it seems to me that we spend a major portion of our life rushing around like maniacs. I have great envy for some of my predecessors who had the luxury of taking a beautiful train and traveling leisurely across the country to visit alumni clubs, or possibly even taking a boat to Europe. That has been replaced by taking the fastest plane, getting out to the airport as quickly as possible, flying into the next city, being met there and rushed to your next appointment. And there are thousands of us. hundreds of thousands if not millions of us, who live our lives according to a schedule like that. We arrive at work tired and irritated, and therefore it is not surprising if we are unpleasant to our colleagues and associates.

In the process we destroy the quality of our environment and we use up our natural resources without any thought at all that other generations may follow us. And yet all the science and technology that is needed to alleviate this great problem and other great problems of society is known today. But we seem to be totally unable to manage it and to bring it to bear on the immediate problems of society. Somehow we can't take our transportation system and try to look at it as a whole. We fail to examine the interaction among the various components; the side effects, outside of the simple questions of how long it takes for a car or a train to get from one point to the other; the effect on the lives of human beings. We fail to examine the psychological impact of this tremendous rush and frustration; the effect on property, on scenic beauty, on the nature of the world we live in. Somehow we do not seem to be able to put this together into a sensible plan on which we can act.

Reaching the moon was a great achievement for man, and I for one am glad and proud that mankind has achieved this. What I can't understand is why we seem to be totally unable to mount a similar effort, for example, to design a reasonable transportation system for the United States. But perhaps this is because between earth and moon you do not find one hundred different political subdivisions. Perhaps it is because there is no opportunity for get-rich-quick schemes on the moon at the present time. Perhaps it is because we were not asked in this to make direct personal sacrifices for the betterment of mankind. Or perhaps it was because there once was a President of the United States who inspired the entire nation in a great goal and in a great concerted national effort that took us to the moon.

Thayer School enters its second century at a critical moment in the history of our country. If we continue the present path of inability to manage the great resources and great scientific and technological know-how available to us, we will witness the decline and fall of a great nation. But if we learn how to channel the miracles of modern technology for the benefit of mankind, we could be at the threshold of a new golden age.

Members of the Class of 1975, the future is in the hands of your generation.

*The reference is the creation of the 30 cent fare, not the current controversy.

The College's 202nd opening exercises, at which PresidentJohn Kemeny spoke, were returned this year to Webster Hall.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

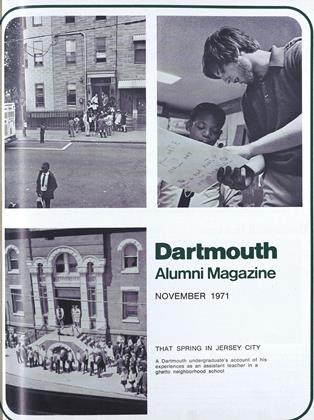

FeatureThat Spring in Jersey City

November 1971 By BRUCE ALAN KIMBALL '73 -

Feature

FeatureThe View from Oxford

November 1971 By Sanford B. Ferguson '70 -

Feature

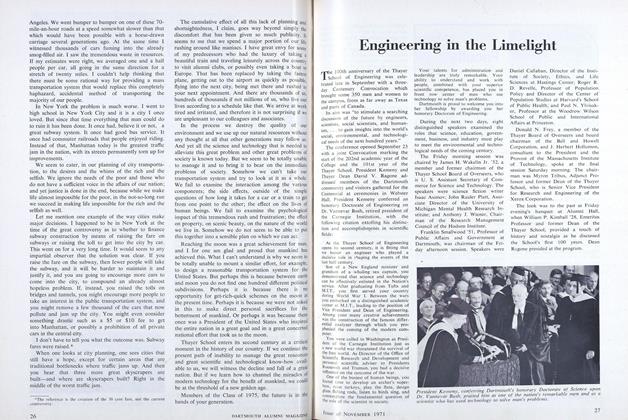

FeatureEngineering in the Limelight

November 1971 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1971 By JACK DEGANGH -

Article

ArticleFaculty

November 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

November 1971 By WALTER S. YUSEN, WILLIAM C. VAN LAW JR

Features

-

Feature

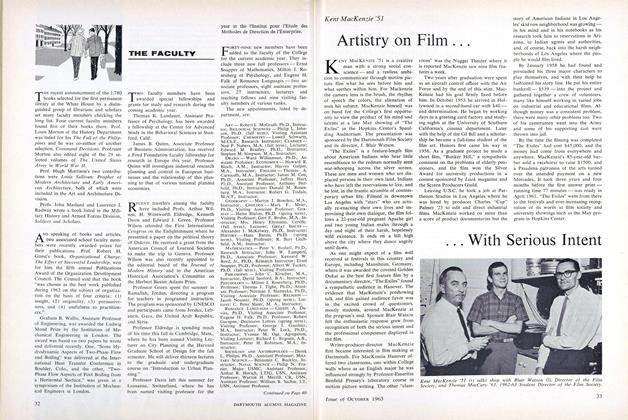

FeatureArtistry on Film ... ... With Serious Intent

OCTOBER 1963 -

Feature

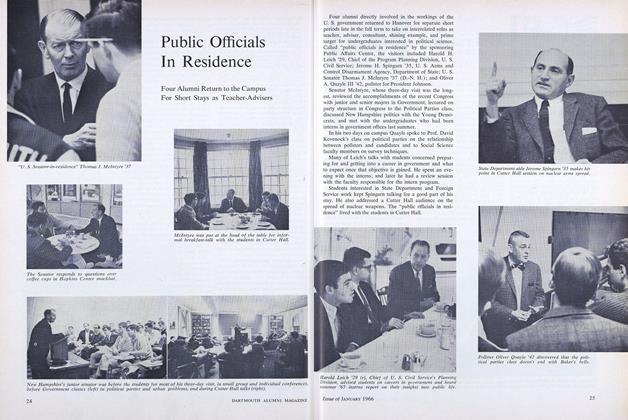

FeaturePublic Officials In Residence

JANUARY 1966 -

Feature

FeatureHall of Hallmark

DECEMBER 1972 -

Feature

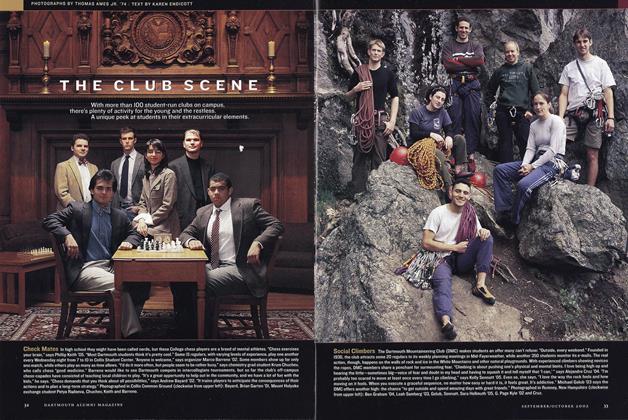

FeatureThe Club Scene

Sept/Oct 2002 -

Feature

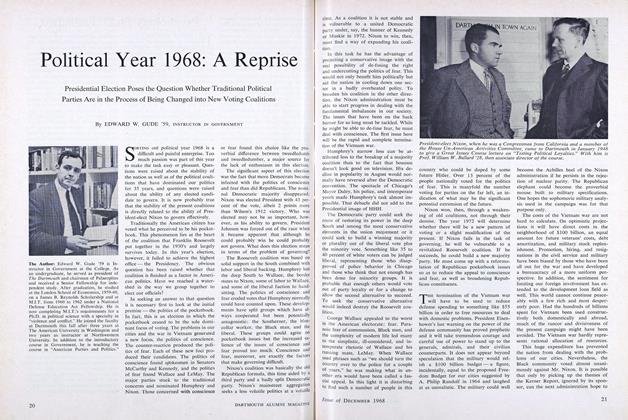

FeaturePolitical Year 1968: A Reprise

DECEMBER 1968 By EDWARD W. GUDE '59, INSTRUCTOR IN GOVERNMENT -

Feature

FeatureThe Mold

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Warren Cook '67