It is not uncommon to hear graduates of either Oxford or Cambridge assert with a certain pride that the quality of education they received is incomparably superior to anything offered in the United States. This disparity, they believe, rests in part on the emphasis we place on educating large numbers of our people. English arrogance aside, American educators have long agreed that one of the central dilemmas we face in this country is to maximize the quality of our education within the constraint of providing education on a mass level.

The tutorial method of education as practiced at Oxford and Cambridge has long been acknowledged by many of our educators as being a superior method in terms of quality; a few have even likened it to a modern-day version of the Platonic ideal. Can it be practiced on a mass level? Attempts have been made at institutions like Dartmouth to adapt certain elements of the tutorial method, but such piecemeal adaptation has often overlooked the crucial elements of the method. Thus we have not achieved the hoped-for results.

The question I would like to try to face up to here is the determination of the elements which make for the success of the tutorial method as practiced at Oxford and Cambridge, and to ask whether those elements might not be used to modify the existing educational method at Dartmouth while still operating within the constraint of providing mass education with limited resources.

The mechanics of the tutorial method become somewhat clearer when we place them against those of the system used at Dartmouth, which will be referred to here as the "classroom-lecture" method. While the classroom-lecture method has been subject to a large amount of variation at Dartmouth within the past few years, its central feature remains the presentation of material in an organized form by the teacher in a classroom. This is supplemented by specific, limited textbook readings closely related to (if not duplicating) the material presented in the classroom, occasional classroom discussions, and less frequent discussions on an informal basis with the teacher outside the classroom. Examinations of one sort or another are frequent, and term papers occasionally require that the student do some work beyond the predetermined path of his instructor.

Consider now the mechanics of the tutorial method as practiced at Oxford and Cambridge. While again variations are found among the various disciplines, a general pattern can be identified. The goal towards which each student works is the marathon examinations he faces at the end of his degree program. With the exception of occasional comments from his tutor, these examinations are the sole basis upon which the quality of a student's work is judged. In preparation for the examinations, the student meets frequently with his tutor in a session known as the tutorial, usually on a weekly basis, and usually by himself or with one other student. The basis of the tutorial is always the submission of work written or prepared by the student since the last tutorial. In subjects such as mathematics or classics the student will have been set a particular exercise which the tutor will criticize, suggesting improvements in method or phraseology. In subjects such as history, philosophy, or literature the student will bring an essay to be read to the tutor. After the essay is read the tutor will offer criticisms and comments, both on the substance and the manner of presentation.

If the tutorial is attended by more than one student, generally only one essay is read. The others are left for the tutor to read, and are given back the following week with the tutor's comments (which are normally quite extensive). Each essay is in response to a specific question, agreed upon in advance by the student and tutor. These questions are chosen both for their interest to the student and for their ability to focus the student's attention on at least one of the crucial problems of the material being prepared for the week. The tutor will suggest a wide and often insurmountable list of readings to be undertaken in preparation for the essay. These readings normally take the student to primary source material, rather than to textbooks.

Considering one goal of education — that of providing information to the student—these two methods of education are probably equal in terms of their results. In fact, from this point of view, we can probably claim that American efficiency has once again triumphed, for the mass-lecture is perhaps one of the most economical ways to disseminate information. Oxford and Cambridge have not failed to recognize this, and regularly supplement the tutorial work with lectures which have as their explicit purpose the dissemination of information. The quality of their lectures is generally lower than ours, due in part to the lesser importance attached to them.

Acquiring information is only one goal of education, however, and a secondary goal at that. The primary goal has been, and ought to continue to be, to learn to think for oneself. It is in pursuit of this goal that our educational method takes second place to that of the tutorial method. Compare the mechanics of the two. Under the tutorial method, a student has to offer extensive work of his own once a week for criticism. Under the classroom-lecture method a student does so generally only two or three times a term. The tutorial student is therefore forced to think more often. Further, the student's work is criticized and encouraged more often. Under both methods, the student's program is given adequate direction by the teacher; but under the tutorial method it is the student's thinking which is directed. Under the classroom-lecture method it is more often than not the teacher's thinking that is directed while the student follows along.

The mechanics of the two methods have a direct influence on student motivation. Under the tutorial method, it is relatively difficult to develop a sense of competitiveness in terms of outdoing one's fellow students. In fact, it is rather difficult to know just who one's competitors are. There is no classroom in which they can be identified and compared, and lectures are few and sparsely attended. Similarly, it is rather difficult to know just how one is doing in relation to others. The tutor will often indicate what he considers to be the quality of one's essay, but that is the only standard of evaluation available other than the final examinations. Competitiveness under the tutorial method then is a far less important source of student motivation. One must rely more heavily on personal pride and an intrinsic interest in the subject matter. The fact that an essay has to be read to an expert and critical audience is crucial. In a classroom, it is all too easy to hide among the faceless mass and lose all feeling of having ones own work exposed. In the tutorial, the spotlight is on the individual student, and the tutor (who will often appear to have malicious intent) is out to explore the depth of the student's thinking. In such a Situation, pride and a genuine interest in the subject will spur the student on. Competitiveness (other than matching debating skills with the tutor) has little place. The immediate goal for the student under the tutorial method, then, is not to out-perform his fellow students in a course examination, but rather to present and defend successfully a point of view as expressed in a weekly essay.

The final fundamental difference be- tween the two methods is the degree to which the academic program is standardized. As one student described his work at Dartmouth, all he had to do was show up, assimilate the already organized material, and then regurgitate it on the examinations. The students who did this well were rewarded with high grades. The course that demanded any great amount of individual thinking was an exception. This feeling about the educational experience at Dartmouth seems to be widely shared by those who have given it consideration. The justification for this pattern is the demand for the education of large numbers of students; the easiest way to handle large numbers, both in terms of the primary learning experience and in terms of evaluating a student's work, is through standardization. And as a result, the teacher does much of the basic thinking for the student. This is a partly misdirected effort on the part of the teacher, whose time should be spent more on directing, criticizing, and encouraging the student's own thinking.

Is it possible for a teacher under our method to spend more time in developing an individual student's thinking? Does this not come into direct conflict with the constraint of educating large numbers of students? This is not necessarily the case. Within the present structure of the classroom-lecture method, and with modifications of the method, greater attention can be given to teaching a student to think for himself. The first requirement is to acknowledge that this is the primary goal. The dissemination of information and other people's ideas is secondary.

If we do accept the premise that our first goal is to help students to think for themselves, then a number of alterations in our present method begin to suggest all too easy to hide among the faceless themselves. Clearly, an outright adoption of the tutorial method is impossible. Oxford, for instance, finds it necessary to maintain a 1:7 faculty-to-student ratio, whereas Dartmouth at present considers itself fortunate to have a 1:12 ratio. Nevertheless, modifications can be made within the present structure which might "bring us closer to achieving the primary goal. For instance, courses offered for freshmen might be considerably smaller, if not offering individual tutorials outright. This would imply increasing the size of upperclass courses if it is to be done without additional resources. The advantage would be to encourage the freshman to think for himself at the very start of his college experience. The classroom-lecture situation can come at a later stage when he is better able to fend for himself. This type of structural modification has been carried out to a certain extent with the Freshman Seminars, but has not been carried far enough. The "survey courses for freshmen ought to be abolished under this argument. Even within the existing structure, the possibilities for improvement are numerous. Rather than pre- packaged, easily managed reading assignments, teachers might instead suggest a wide range of relevant readings, suggesting a particular question which the student ought to be considering as he goes through it. Written work could be demanded far more often, to be presented for criticism to subgroups of the entire class or to individual students. Lectures could be diminished in number—anticipating that students could acquire the same information through reading—with the intention of providing the teacher more time to work individually with his students.

These mechanical changes are by no means exhaustive. My intention has been simply to indicate the kind of change which could be beneficial. Yet while mechanical changes come easily, the difficult change will be in the spirit of teaching. Acquiring and disseminating information is relatively easy, but to help a student think for himself requires a real personal involvement on the part of the teacher. To shift the spirit of teaching to this latter goal is the most important thing that can be done to temper the Englishmen's criticism, but it will also be the most difficult.

As a final note, it might be useful to mention here the emotional reaction which recent American students have had to the tutorial method. Without exception they give high praise to its pedagogical merit, yet many are unhappy with its demands. A frequent criticism is that it is "too structured." This may be an emotional reaction rather than a pedagogical one, for the tutorial method is about as unstructured as one could get. A high premium is placed on indepen- dence and freedom. A student's time is entirely his own, with the exception of the weekly tutorial. Tutors are generally willing to follow wherever the whims of the student will lead, so long as the student is able to justify his whim within the context of his overall interest. Structure is imposed only in the sense that the thought of the final examinations is at least subconsciously ever present. The criticism of the method as being too structured is misplaced. The underlying feeling which motivates this criticism may be that the vastly increased freedom and independence are an uncomfortable mode of operation for the American student. The increased freedom and independence necessarily carry with them an increased responsibility. The student, under the tutorial method, must share responsibility for his own education. The converse applies to the classroom-lecture method, and it may be the clash between the two which makes the American student uncomfortable within the tutorial context. If it is true that responsibility is best developed by exercising it, then this becomes a further argument for reconsidering the spirit and mechanics which we presently apply to our educational method.

Sanford B. Ferguson '70 of Pittsburgh, Pa., is studying at Oxford University thisyear on a James B. Reynolds Scholarship for Foreign Study. A mathematics majorat Dartmouth, he is working at Jesus College toward an Honors B.A. in Philosophy-Politics-Economics. He plans to enter law school on his return to this country nextyear. His father is Dr. Albert B. Ferguson Jr. '4l, his brother Bruce K. Ferguson '71.During his undergraduate years Sandy was a member of Casque and Gauntlet, captainof the lightweight crew, and won the Breer Cup as outstanding lightweight oarsman.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThat Spring in Jersey City

November 1971 By BRUCE ALAN KIMBALL '73 -

Feature

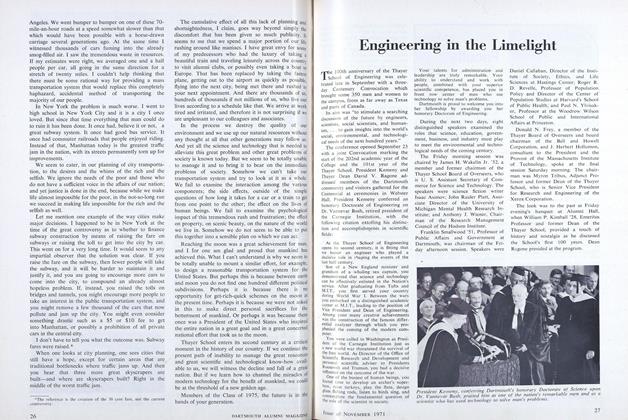

FeatureThe President's Convocation Address

November 1971 -

Feature

FeatureEngineering in the Limelight

November 1971 -

Article

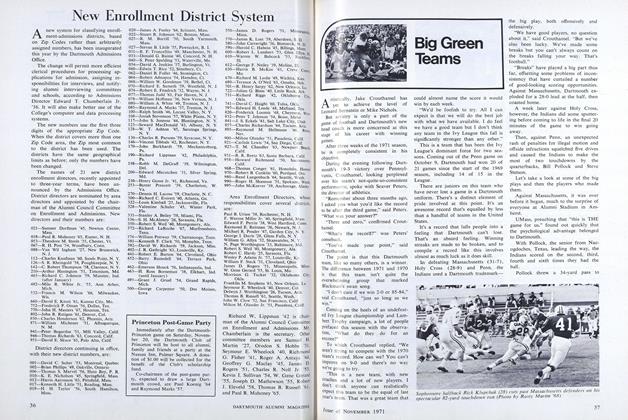

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1971 By JACK DEGANGH -

Article

ArticleFaculty

November 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

November 1971 By WALTER S. YUSEN, WILLIAM C. VAN LAW JR

Sanford B. Ferguson '70

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePROJECT ABC

JANUARY 1964 -

Features

Features“A Fierce Advocate”

MAY | JUNE 2025 By GRACE BROWNE -

Feature

FeaturePEDAGUESE MADE EASY

MARCH 1966 By James S. LeSure '35 -

Feature

FeatureThe Woman Who Was Not All There

June 1992 By Paula Sharp '79 -

Feature

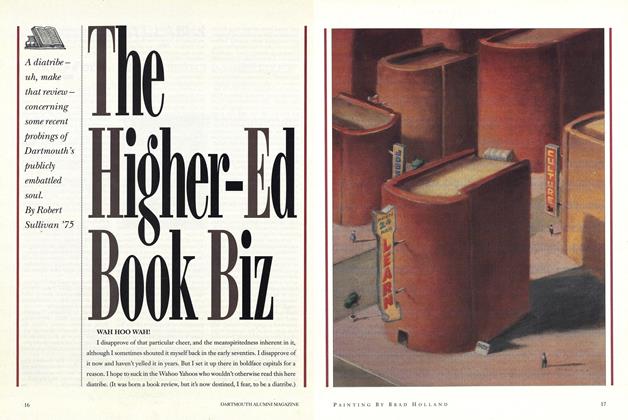

FeatureThe Higher-Ed Book Biz

JUNE 1991 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWell-Earned Minus

MARCH 1995 By William C. Sadd '62