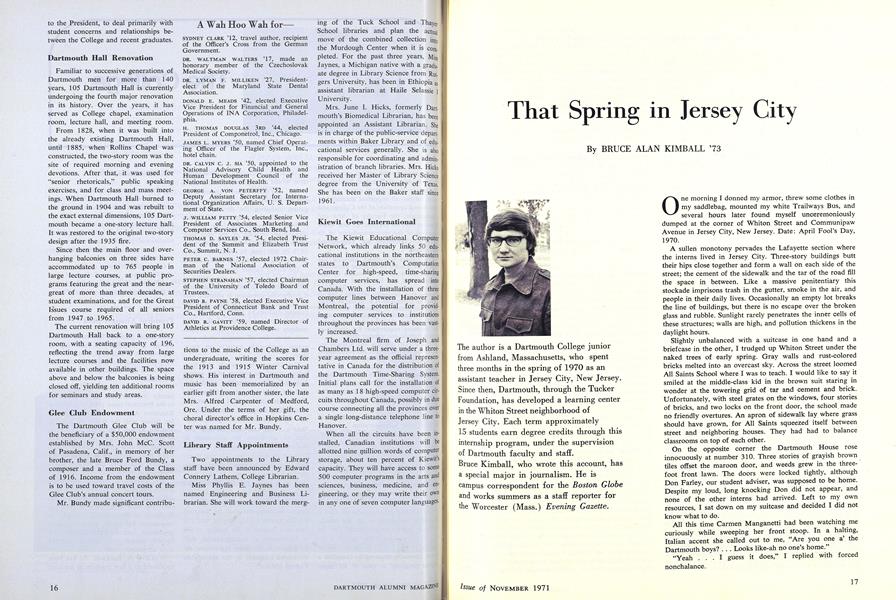

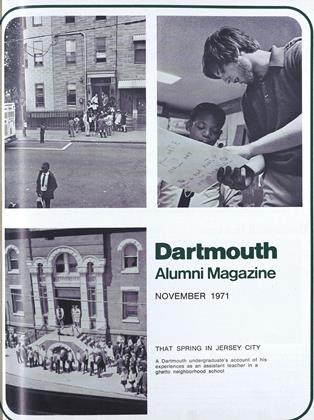

The author is a Dartmouth College junior from Ashland, Massachusetts, who spent three months in the spring of 1970 as an assistant teacher in Jersey City, New Jersey. Since then, Dartmouth, through the Tucker Foundation, has developed a learning center in the Whiton Street neighborhood of Jersey City. Each term approximately 15 students earn degree credits through this internship program, under the supervision of Dartmouth faculty and staff. Bruce Kimball, who wrote this account, has a special major in journalism. He is campus correspondent for the Boston Globe and works summers as a staff reporter for the Worcester (Mass.) Evening Gazette.

One morning I donned my armor, threw some clothes in my saddlebag, mounted my white Trailways Bus, and several hours later found myself unceremoniously dumped at the corner of Whiton Street and Communipaw Avenue in Jersey City, New Jersey. Date: April Fool's Day, 1970.

A sullen monotony pervades the Lafayette section where the interns lived in Jersey City. Three-story buildings butt their hips close together and form a wall on each side of the street; the cement of the sidewalk and the tar of the road fill the space in between. Like a massive penitentiary this stockade imprisons trash in the gutter, smoke in the air, and people in their daily lives. Occasionally an empty lot breaks the line of buildings, but there is no escape over the broken glass and rubble. Sunlight rarely penetrates the inner cells of these structures; walls are high, and pollution thickens in the daylight hours.

Slightly unbalanced with a suitcase in one hand and a briefcase in the other, I trudged up Whiton Street under the naked trees of early spring. Gray walls and rust-colored bricks melted into an overcast sky. Across the street loomed All Saints School where I was to teach. I would like to say it smiled at the middle-class kid in the brown suit staring in wonder at the towering grid of tar and cement and brick. Unfortunately, with steel grates on the windows, four stories of bricks, and two locks on the front door, the school, made no friendly overtures. An apron of sidewalk lay where grass should have grown, for All Saints squeezed itself between street and neighboring houses. They had had to balance classrooms on top of each other.

On the opposite corner the Dartmouth House rose innocuously at number 310. Three stories of grayish brown tiles offset the maroon door, and weeds grew in the three-foot front lawn. The doors were locked tightly, although Don Farley, our student adviser, was supposed to be home. Despite my loud, long knocking Don did not appear, and none of the other interns had arrived. Left to my own resources, I sat down on my suitcase and decided I did not know what to do.

All this time Carmen Manganetti had been watching me curiously while sweeping her front stoop. In a halting, Italian accent she called out to me, "Are you one a' the Dartmouth boys?... Looks like-ah no one's home."

"Yeah... I guess it does," I replied with forced nonchalance.

Sensing that, Carmen took me under her wing: "Come over my house an' we call Father. He put you at the Rectory for the night."

Gratefully I picked up my bags and followed Carmen up the steps to the second floor of the neighboring house while she chattered away endlessly. Her hips spread across the width of the stairway, and her flabby arm shook when she pulled on the railing. As Carmen clumped up the stairs in front of me, I watched the roll of her huge buttocks that stared me in the face. She was bursting the seams of a tent dress, and I knew a massive heart lay beneath that mountain of flesh.

We reached her apartment in the midst of questions about my past, present, and future, for her motherly instinct was rapidly warming. The four-room flat appeared neat and tidy with a crucifix or a picture of Christ on almost every wall. I found the phone book beneath a volume of the Old Testament and called Father O'Malley of All Saints Church. He promised to pick me up in ten minutes.

I thanked Carmen, but she just shrugged and told me to visit her often. Then she lowered her voice in maternal concern and offered me one last bit of advice about Jersey City. "Now don't you go makin' the same mistake that the other boys did. They let all those colored kids run around in the Dartmouth House, and all kinds of things were stolen. Enough is enough, and a little bit is OK, but don't let those colored kids take advantage of your goodheartedness... and be sure to visit me... bye."

Between the overcast sky and the gray cement of the sidewalk I waited for Father O'Malley and thought of Carmen's warning. Somehow this whispered precaution seemed to hold more bias than truth. Pretending that the children did not need a place to play offered no solution to the problem. Things had been stolen from the residence, but the interns always let the kids back in. Each new flood of interns brought more hope and great plans for the schools and the city. We were arriving with ours.

Yet the image of Carmen's fat hung on, and as the weeks were to pass this picture grew stronger and more distasteful On the buses, in the stores, and on the porches at night loomed the decaying bodies of citizens. White, black, and brown masses of flesh sweated out the warm spring nights and triple chins dripped over collars. In the midst of this festering city people abuse their final resource until it becomes a tired, fleshy burden long before its time. The degradation of Jersey City does not halt at the trash in the street or stench of pollution in the air. The environment prostitutes the minds and bodies of the people, and this little WASP had already been stung.

As Father Stephen O'Malley walked up the street I peered anxiously at his priestly figure. Before arriving in Jersey City I rarely had the opportunity to speak to any Catholic clergy, so my uncertainty heightened as he approached, but his youthful features and sincere smile dissolved my anxiety as we discussed my homelessness. Father O'Malley revealed himself to be an independent person and held no pretensions about the priesthood. Later when we began to work together, I even called him "Steve" which is quite a thrill for a Protestant backeaster.

After unpacking at the Rectory we took a short tour of Lafayette that only served to strengthen my first impressions. An endless network of tar streets carved blocks from the lines of three-story buildings. Windows were either boarded, broken or dirty; and all wooden trim needed paint. Men and teenagers leaned against the walls of dimly lit bars; women and girls talked across collapsing fences; children played in the street. The trip concluded with the Lafayette Garden Projects which were built twenty years ago as models for urban housing. Today the most vile elements of the offensive atmosphere concentrate here. Roaches, cold cement, paper walls, rats, and the smell of urine linger in each and every building. After absorbing these surroundings, we drove back to the Rectory where I paused to savor the feel of the carpet beneath my feet.

At supper Father O'Malley and I sat down to ham, sweet potatoes, and corn served on silver platters. I cursed to myself after dropping a bit of food on the immaculate linen tablecloth. A stereo played softly in the background as we discussed the role of the Catholic Church in a modern society over a dessert of fresh strawberries.

"Father, what's the Church doing to help Jersey City? Everything just seems so dirty and decayed around here... How can you fight these social conditions without something like birth control?"

I began the conversation rather hesitantly because I halfexpected a Catholic priest to begin spouting rhetoric as soon as I attacked the institution he stood for. My conception of the priesthood was really distorted. Steve sincerely desired to help the people of Jersey City, and yet he said he was caught between the dictates of his institution and practical necessity. Suddenly I began to sense the deep conflict within the man as his eyes grew troubled. He explained that Jersey City needed political and social action from its clergy, but he was tightly shackled by the Church's traditional aloofness and the people's conventional expectations of the role he should play. Occasionally he swore quietly in total frustration of his futility; I remember thinking at the time that I had never heard a priest swear before, but somehow the depth of Steve's feeling seemed to warrant it. The conversation ventured far and wide; yet we always returned to Steve's conflict with tradition.

"Doctrine starts with the Pope and gets passed down to the cardinals and bishops. They're old men, and they live in a different world. Priests are taught to respect and obey the hierarchy, and they're often old men themselves.... Ideas kick around so long that people learn to hang on to them. They get uneasy when the old beliefs are replaced or altered. Everyone is left sitting in the same pile of bullshit..."

My mind immediately created the picture of Jersey City, with all its priests, ministers, churches, and people plopped in the middle of a big pile of bullshit. I chuckled inside although I suppose that is terribly sacrilegious. However sacrilege did not matter at that point. Carmen Manganetti had her walls plastered with religious symbols, but that still did not help her understand "those colored kids."

We sat in subdued meditation until the cook entered to carry off the dishes. The bubble of abstract thought quietly popped. Suddenly I began to feel guilty about sitting in the comparative luxury of the Rectory and condemning others for not helping people in the surrounding ghetto. I had forgotten that I was barely introduced to the environment. Luckily words remain inexpensive in our modern economy.

A kaleidoscope of ideas whirled madly in my brain as I climbed the stairs to my bedroom. How was I to cope with these novel thoughts? Every new influence seemed bent on tearing me from my childhood teachings. I slipped into bed asking myself what I was doing in the rectory of a Catholic church in the middle of a ghetto in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Don Farley returned to the Dartmouth house the next morning so I repacked my suitcase, thanked Father O'Malley, and moved in at 310 Whiton Street. My third floor double room was a far cry from the Rectory; the house in general begged for repair. At the time I was rather surprised that Dartmouth expected me to pay room, board, and tuition to live in a house that was falling apart.

Two mattresses on the floor served as beds, and the lone desk held only one of its original four drawers. An unfinished old bureau sat forlornly in one corner, and a clothes cabinet leaned precariously in the other. Previous interns had left a couple dozen elementary textbooks scattered around the room. Stacks of worksheets and workbooks were piled on the cabinet, the bureau, the desk, and the linoleum floor. The two corner windows that brightened the blue walls also gave an excellent view of the intersection of Whiton and Lafayette Streets. Our only shade, refusing to work, hung limply but looked quite decorative. Someone had painted it with flowers, a peace sign, an American flag, the word "WUV," and several slogans. I laughed when I read that "Learning is a constant restatement of the word 'Yes!' " Soon I would discover the sad hypocrisy of that sentence. The other two walls each had pairs of sliding double doors which revealed that the house once held apartments. Neither of the sets of doors fitted its portal so a large crack was left where one could peer into the next room. On the floor, paint chips from the ceiling cartwheeled in the early morning breeze. After a courageous look I promptly decided to search out a vacuum cleaner and at least tidy my kingdom. This hunt led me to investigate the rest of the house.

Everything was patterned after my room. Papers littered the floor, and paint was chipped off the walls. Dartmouth alumni had donated most of the furniture—and must have been glad to see it go. The only bright spots, in the house were the two new showers that had been built by past interns. The one on the third floor was composed of reinforced concrete and the one on the second floor of 960 soda cans. Previously one bathtub served all sixteen men in the house.

I returned from my forage with the vacuum cleaner and many other prizes including an old floor lamp, a rickety chair, and a worn brown rug. After a couple hours of diligent effort the room was reasonably clean; my treasures were put in place, and all my belongings unpacked. The empty suitcase made an excellent night table, and the floor lamp promised to be a valuable asset, as soon as I found some light bulbs. With that task completed, 1 started to explore the neighborhood by myself, since none of the other interns had arrived.

A small boy was building a dam in the gutter of the street, and I greeted him with a smiling "Hello Tiger!" He was black and could not have been more than four or five years old. Despite my urging, he refused to talk until I turned to leave. Then he looked up at me and asked very sweetly, "Do you have a nickel?"

As green as I am, I knew I had been chosen as an easy mark. I was determined not to assume the role of a disinterested white benefactor to the kids I met, but my tongue tied itself in a large square knot. In spite of my expectation of this kind of situation, I did not suppose that a four-year-old child would ask for money. There seemed to be no proper way to deal with the question. After untying my tongue, I managed to lie that I did not have any money, and I stalked away. Angrily I berated myself for not being ready for the question and blamed the kid for asking me when he knew I was not ready. He just shrugged and turned back to his dam.

Regaining my composure I walked a few more blocks and arrived at Lafayette Park. A scraggy football field lay side by side with a tar basketball court. The rims were bent, and the nets were nonexistent. I had taken a balding basketball to the city hoping to start some sort of league. Now it appeared that the facilities would be limited or even unusable. The other half of the park held tree-shaded walks and benches which did the kids little good, and I rarely saw any adults in the park. That day some black eighth-graders were playing hoop so I stepped in to join them. We had a game of X's and enjoyed each other's company. However, the golden notes of "motherfucker" resounded again and again across the tar. Black youths seem to have a special affinity for that word. They apply it to everyone and everything in Jersey City. Perhaps the epithet represents the black hate of miscegenation for the emasculation it has meant to their race. In any case, I kept searching for an explanation of the hardened attitudes that surrounded me.

While heading back to the house I passed Public School #22 and the nuns' convent. P.S. #22, the third largest elementary school in the country, holds approximately 2000 children in grades 1 through 8. From the outside it looks like a modern learning center, but the student body consists of many "problem children" who do not have the money or the inclination to go to the better Catholic schools. Thus the eighth grade includes a large segment of sixteen and seventeen-year-olds whom I met on the basketball court at Lafayette Park. Actually, it is ironic to call the Catholic schools better than the public schools because the difference lies in faculty devotion. In general the public school system had much better facilities than the private schools could offer, but the nuns devote themselves to the children while many other urban teachers go to school solely to punch their timeclock.

As I gazed at All Saints Convent, I wondered how I would fare in the eyes of the nuns. At the same time I could not help noticing how the Convent outclassed the rest of the neighborhood-with the exception of the church and the rectory. The Catholic clergy really deserve good quarters for the work they do, although it must be difficult for a ghetto resident to relate to a priest when he knows the clergyman will return to a comfortable rectory at night. Unfortunately, many of man's attitudes depend on money and comfort. We are a physical animal first, and a spiritual animal last.

Meanwhile, Paul Ricardi, Andy Larson, Jose Quijo, and Tony Carchio had arrived at the residence. These four taught at Saint Bridget's Elementary School, and Jose and Paul lived in an apartment near the school. By the time I returned from my walk Tony and Andy had chosen rooms in the house and unpacked. In the next few hours, four more interns straggled in. Like a wise, old sage I sat in the living room and enjoyed the amazement of the "inexperienced" new interns as they entered. I tried to act as if I was at ease in the middle of the dirty city, but inside I was bubbling to recount all my experiences of the past two days. Kenny Hamilton and Tom Sirota took rooms on the second floor and went upstairs to get squared away, but Cliff Brown and Ralph Letner, two engineering students who were assigned to a local high school, just dropped their bags on the third floor and came back downstairs to look for some action.

Cliff plopped down in the sagging old armchair and pronounced, "Everything is so damn filthy around here!" Ralph and I agreed, and the three of us decided to venture outside and see the nightlife of Jersey City.

The evening chill of early spring closed over the streets. The starkness of empty sidewalks quieted our idle talk. Rows of street lights led eternally to the obscure corners of the city; we drank deeply of the lonely gray musk of the night air. Only the bars opened their doors and beckoned patrons into their dark womb. After a few blocks we retraced our steps, immersed in our own quiet thoughts, punctuated by Cliff's occasional exclamations, "Jesus, how do these people live here?" As we entered the house, only the faroff squeal of tires and tinkle of broken glass cracked the shield of darkness over the night.

On Monday Sister Carolyn, principal at All Saints, held a teachers' meeting so the new interns could orient themselves to the school's curriculum. The five of us nervously awaited the start of classes. Ken Hamilton, Tom Sirota, Wally Paterson, Barbara Lindsay, and I were all assigned to teach at All Saints; but at this point each of them was still an anonymous face in the crowd of lives one encounters during youth. Soon I knew and worked with them individually. As we leaped to accomplishments and stumbled across frustration during the term each intern began to appreciate the others more and more. But looking back, it seemed as if we were doing a lot more stumbling then leaping.

Like courageous but foolhardy musketeers, we five found our way to the library. There we met the ten regular members of All Saints' faculty—six sisters, four others, and also Sister Carolyn. Conscious of our inexperience, we advanced hesitantly, but everyone immediately set us at ease with smiles and words of greeting. As soon as we lowered our guard, the teachers presented us with orientation gifts—class assignments for the following day. Then Sister Carolyn officially introduced us:

"As in the past, the Dartmouth students will have complete jurisdiction within their own classrooms. Occasionally I'll be listening to your classes to evaluate you, but basically you'll be on your own. Each Dartmouth student will be working with a certain faculty member to consider curriculum and teaching methods for each class... uh... I hope you'll sit in on each other's classes to observe different techniques... Let's see... I also wanted to explain the grouping method in the sixth, seventh, and eighth grades for math, English, and reading. These top three grades are lumped together and then divided into six groups, according to ability. This allows us to concentrate on specific problems of students regardless of grade level. You'll find that your classes in math, English, and reading are mixtures of the three top grades... but you can straighten out any questions on subject matter with the teacher who advises you... Well, I... oh yes—I just wanted you to remember to have confidence when you walk into your classes. Our kids are wonderful kids—they really are. Only don't back down to them, because they'll walk all over you... They have to understand that you're in charge."

In a whirl of advice and precautions the faculty descended on us and explained the subject matter in detail, all together, all at once, without stopping. I staggered out of the school with the friendly counsel of Sister Hellen ringing in my ears. She worked with me in Group 3 Math, Group 6 Math, and sixth-grade Science. Group 4 Reading held both great potential and pitfalls warned Sister Martha, the reading teacher. Last, good old Mrs. Johnson gleefully told me about the seven third-graders I was to tutor in reading. At the time I thought Mrs. Johnson sighed with relief to see the meeting end. Only later did I discover that she was merely glad to see part of her class out of her hair.

Faced with the impending doom of tomorrow's dawn, I wearily trudged up to the room to prepare lessons. Wally, my roommate, followed close behind me muttering, "Man, this is awesome!" I chickened out after rereading my schedule and decided that I would first let John Holt tell me Why Children Fail.

As I delved further and further into the book, my anticipation turned to foreboding which turned to horror at the prospect of facing little furies who used all the tricks that Holt described. Wally and I began to debate how much a thirteen-year-old would challenge a new young teacher. With fright we recalled the fiendish tricks that we had once played on substitute teachers.

"But the kids can't be that bad, Bruce; I mean they're still kids... Aren't they?... Hell, we're getting too caught up in the problem. If we treat the students like people, they won't give us trouble. We've got to show them that we respect them, but that we won't take any bullshit from them..."

Such a beautiful goal lay before us—an understanding relationship with the children based on mutual respect. Certainly our sincerity would conquer all hang-ups. I actually began to feel confident. With our fears safely locked away in the flimsy box of fantasy, Wally and I wrote lesson plans for the following day.

Long shadows extended across the street when someone rang the buzzer at the front door. I ran all the way downstairs to answer it and found a ten-year-old boy smiling at me with a huge grin. Tyrone grabbed my hand affectionately and invited himself upstairs to watch the old TV in the reading room. Completely taken aback by his forwardness, I simply followed to discover that he knew the house better than I did. Soon I realized that this was his second home, if not his first.

He watched cartoons; I watched him, and we were equally fascinated. Tyrone knew every television commercial by heart and sang along with the jingles. Like a mechanical doll he poured out manufactured pablum about Barbie and Ken, Tonka trucks, toy soldiers, and breakfast cereals. The television entranced him; his mind no longer seemed to function by its own will. I learned that he had never left Jersey City; his only window on the rest of the world was that battered television. His environment consisted of an old decaying city and children's programs about things he will never see with commercials about things he will never own. The picture tube portrayed a world of clean luxury in contrast to the dirt that surrounded him. What does a Tyrone feel when he knows this wealth exists but he will never touch it? ... Perhaps a silent rage slowly builds and one day explodes. My mind fantasized beyond the walls of the room, beyond the house, beyond the city. Meanwhile a small black youth sang the Johnny Lightning jingle and dreamed of a world he will never know.

April seventh and eighth will carry stars on my calendar forever. Within that 48-hour period I had each of my four classes and third-grade students at least once. Let the entries of my journal stand as history:

April 7, 1970

First period brought my initial experience in the jungle of education; I tutored three Puerto Rican boys who are supposed to be slow in reading. I walked into good old Mrs. Johnson's class to get them, and she asked me what skills I thought they should work on! How in the hell do I know what their weaknesses are if I've never even met them? Mrs. Johnson must have noticed my astonishment because she gave me a reader and told me to take them out of the class somewhere. Nervously I walked down the hall with Roberto, Don, and Luis, expecting them to trip over their shoelaces or something dullard like that. We sat down to work and—SURPRISE! These kids are bright and enthusiastic. Their eyes really sparkle, and they look delighted when they work something out. I can't believe that they are considered "slow." Somehow they must have been lost in the shuffle of an urban classroom. Roberto, Don, and Luis all have Spanish-speaking parents who know very little English; thus their vocabulary is very limited. But tutoring them is really enjoyable because they are so rambunctious and yet will pay attention when I speak to them—so we get someplace.

Second period I had Group 3 in Math which is a combination of sixth and seventh-graders. Sister Hellen wants me to have them adding and subtracting fractions, which is all new material, by the end of the term. This morning we just felt each other out, and I must say I had good control of the class. I hope I am impressing them and giving them some spirit with my enthusiasm. We only meet on Tuesdays and Thursdays, but I plan to give them a quiz next week about finding the Least Common Multiple of two numbers.

Discouragement follows triumph I guess. Diego and Raquel, whom I tutored third period, need an awful lot of help. I fear that Mrs. Johnson or somebody has botched them up terribly. It's as if they never went to school; they guess randomly at words with no care for construction or sound or anything. We're going to return to some basic phonics and see if they can begin to tear words apart.

Science comes last period with my class of 36 sixth- graders. It was hell for the first thirty minutes, but I think I'll pull through because the kids will see that I really want to teach them something. Our unit for the term is Air Pollution.

I entered the classroom promising myself that I would not yell and promptly chose to shout instead. Six kids jumped me with requests to visit the bathroom. Roger Vernon and Peter Wallace were throwing a football across the room. I confiscated the ball, but they stole it back when I turned to ask the male assailant to return the pocketbook of a young lady who had flirted with the boy in front of her after he clobbered his neighbor with a ruler for stealing the book of a friend who had no business being on that side of the room to begin with. In short, I walked into bedlam and found there was no way to clamp down the lid of authority.

Earl Fleming provided a unique episode in himself. He is a rather taunting, rebellious young black who refuses to submit to the call of the learned. (That's me!) Finally, I got fed up with his pocketbook snatching, ruler snapping, and book throwing and demanded that he sit in the corner. He sauntered up to me and said that he wanted only to go the lavatory, which is why he left his seat. Rather than try to force him into the corner, which he had no intention of entering, I decided that it was better if he just leave the room—to the lavatory. He went; I turned to reprimand another impudent young angel, and Earl stole my only piece of chalk on the way out. What's a mother to do?

About this time I turned to the Silent Treatment. I just stood up front and calmly watched until they sshhed each other down. Then I proclaimed that I had no intention of competing with them. If they wanted to discuss Air Pollution, then we could have a good class; but I was not going to chase them in 36 different directions. Next I threatened them with an exam next Tuesday which would have a certain amount of material on it—whether or not they allowed me to cover that material. From there, one half-hour after the period began, I started to teach.

Five minutes later we had a fire drill.

The kids grabbed coats, books, pencils, and football and fled. The last thing I remember is the sight of the football hitting the neon light fixture and the sound of retreating cloven feet.

The few minutes I taught about air pollution went very well. The kids are easy to interest because they have such a warped view of the universe and the world. They equated air with oxygen and had no idea that the atmosphere contains other gases. That's when teaching becomes exciting and satisfying.

Tonight Wally, Ken, Tom, and I traded experiences of the day. We agreed that discipline was necessary to get anything across to the students—also that none of us had established any discipline in our classrooms and therefore probably had gotten nothing across. It was further decided that educational theories do not apply very well to the practical situations. Yet here I am engrossed in another one of these damn education books, Education and Ecstasy, in which George Leonard describes an ideal learning environment. There are no grades, no punishment, no artificial rewards; learning itself becomes the reinforcement for scholarly achievement. Everything fits in so perfectly that I complained jealously to Wally that maybe I was just too incompetent to produce an ideal learning environment in my own classroom. However my roommate thoughtfully points out that George Leonard does not have to face my reading class for the first time tomorrow.

April 8, 1970

The classes generally went well. I'm becoming absorbed in this teaching thing. I don't exactly understand it, but by the end of the day I am completely exhausted and drained.

First, my Group 4 reading class went off—with a hitch. I was very hopeful that great things could be done with the class—records, newspapers, library visits, movies, etc. Actually they were well-behaved until the end of the class when I could not contain them. I had something important to say (I thought.) so I shouted at the top of my voice, "Jesus Christ, can't you kids keep quiet?"

They all hushed promptly and turned to listen with wide eyes. Then I realized that Sister Martha was right next door, and I had violated the religious sanctity of All Saints School. Anyway, it quieted the kids so I am not particularly shamed. Is my responsibility to the children or the dictates of society?

Mrs. Johnson insists on being a nurd rather than a teacher. She considers all of my third-graders to be hopelessly lost, but every one of them seems to be intelligent to me. How can she miss the sparkle in their eyes? Coming from Spanish-speaking families they have a difficult language barrier to overcome for they hear very little English at home.

My science class went better than I had dared hope. I gave Peter Wallace detention and let Earl Fleming deliver the punishment slip to the office to make him feel important and develop some trust in him. Only three or four times was it necessary to shout; most kept in their seats. Still, I suppose the heat might have just sapped their strength for the day. Anyway we got through some Air Pollution. I cannot forget their amazement to learn that air is comprised mostly of nitrogen rather than oxygen.

For the rest of that week we tested each other. Gradually the names of troublemakers and top students became imprinted on my mind. I struggled to remember the other blank faces who had not yet identified themselves with any outstanding traits. How easily a teacher becomes preoccupied with the ends of the spectrum and forgets the majority of children in between! There lies the primary responsibility; yet, what a temptation to coddle the draggers, challenge the leaders, and let the rest shift for themselves. Where is there enough time to aid all three?

Bonds with children strengthened as each intern developed special friendships with different students. After school, during class, and on weekends, the Dartmouth students would find themselves drowning in little kids who desired attention and love. White hands, brown hands, black hands, girls' hands, and boys' hands would pull and tug to be noticed. Their desire to be touched and understood by young men who came from dartmouthcollegeinnewhampshire was all-consuming. Somehow an invisible force drew us close to them. However, try as we might, the image of teacher could not be incorporated into the image of friend. Outside school we exchanged confidences with the children; within the building we were challenged again and again.

Tutoring proved to be an exception, for I maintained a special relationship with each of my third-graders. But above all the rest, Diego captured my heart.

Born in New York City, this chubby boy had moved to Jersey City when he was a baby. Father worked as a janitor, and mother kept a spotless house with the few resources they had. She spoke no English and could not sign her name. Ten-year-old Diego entered school a year late because his parents saw no worth in education. (They must have heard that I was coming to teach.) He stayed back once in first grade, once in second grade, and this was also his second try at third grade. Mrs. Johnson subsequently passed him because he simply became too big for his class.

That first week we met twice and became good friends. The second time I introduced some elementary phonics and ran into a brick wall. Diego took three tries to say the alphabet and did not have the foggiest idea what a vowel or a consonant was. Small wonder he failed to put sounds together even though he tried so hard. His chubby body trembled with the effort while I encouraged him. Whenever he succeeded, a huge smile exploded across his face and the dimples and blue eyes would beam with satisfaction. From that point I determined to start all over again with first-grade phonics and then discovered that the school had no workbooks. About a week later Sister Carolyn scrounged up a teacher's guide, and we used that the rest of the term.

Yet even as my friendship with Diego ripened, I found a mind-bungling conflict presented by the children who visited the house during the afternoon and evening. When were they trying to be friendly and when were they trying to hustle us?

One afternoon I brought two first-graders, Charles and Terissa, into the house to visit. Despite their age, both had stopped me in the street, grabbed my hand, and asked my name. Charles and Terissa promised to be my friends for the term if I brought them inside to watch television.

About this time I had stumbled across two hundred cases of diet soft drink that a bottling company donated to us when cyclamates were banned. We kept the soda in the cellar and gave it freely to the local children whenever they asked. However it became a terrible nuisance to answer the door every two minutes and find a thirsty youngster who invariably asked, "Can I have a soda?" Furthermore, the empty cans ended up in the gutter of Whiton Street, to the wrath of our neighbors. Soon we stopped the practice.

Yet the moment Charles and Terissa got through the door, they clamored for a soda so I weakened and gave it to them. Then they sat down to watch TV, and suddenly I felt uncomfortably like a Roman emperor who dispensed "bread and circus" to the peasants. Only here I offered soda and TV to become an artificial friend. Time and again children came to the door to ask for a soda, constantly holding out their friendship as the plum in exchange. Perhaps my imagination led me to suspect all motives, but soon I grew suspicious of every kid that came to the house. I despised the image of a ghetto child kissing my middle-class shoes because I had soda and TV to give him.

Searching for ulterior motives behind a child's smile brings terrible pain. All the youngsters I knew back home seemed meek and shy compared to these kids. Whether white, black, or brown, these children have been forced to live, by their wits where their strength would not prevail. At first I condemned each and every child who attempted to sell his loyalty. My opinion of the ghetto children dropped lower and lower. Then one day I opened my eyes.

In the street little kids were fighting over toys and candy money and ragged possessions. A pecking order appeared and demanded the strength of the older teenagers to enforce it. Suffocating beneath the tide of a thousand mindless authorities the little ones struggled to survive. Suddenly the thought struck me that these children might find no difference between hustling and carefree friendliness. Perhaps they had been preyed upon ever since they were born and gradually the defense mechanisms evolved. After being struck down so many times, they found that no one can be trusted. Charles and Terissa learned that Jersey City crushes those who choose righteousness over self-interest. What their parents could not or would not provide, they took from the environment through whatever means available. That may not serve as a justification for their actions, but it is an explanation. Also, they pay a price for this makeshift existence—imagine the loneliness of not trusting a friend who may steal your candy money because he has none. Although they would not work in school, these children learned their most important lessons well.

This question of relevant curriculum grew more apparent as the term progressed; Kenny, Tom, Wally and I held countless bull sessions to discuss it. What should be taught to children trapped in a decadent urban environment? What will serve these children best—abstract thought or practicalities?

Educational theorists constantly stress the need for independent study at all grade levels, especially the lower ones. Books like How Children Learn and Teaching as aSubversive Activity make a very strong case for the "messing-around" approach to teaching—a child's innate curiosity will lead him to learn facts and principles if the teacher only provides a stimulus; very little direction is needed. Generally the interns agreed that children soak up knowledge naturally; however, a sticky question remains. Should children be allowed to choose their own area of study and learn only the things which interest them at the present?

As teachers the interns experimented with varying amounts of classroom control—ranging from none in the beginning to absolute tyranny during some parts of the term. Usually, we attempted to institute a free-wheeling type of classroom where the children felt comfortable, but often these adventures resulted in near riots for the students and near breakdowns for the interns. I was having a hard enough time trying to keep my sixth-graders from killing each other, never mind actually putting scientific equipment (potential weapons) in their hands. Also, my first book reports and papers from my reading class were terrible. I received incomplete phrases (not even incomplete sentences), incoherent thoughts, scraps of paper with tiny writing, large scrawly writing to stretch out the report, and blank stares from those who did not submit any work. Somehow the apathetic, uncaring attitude of the kids nurtured my own guilt. Why weren't these kids turned on? How was I failing to reach them?

The Dartmouth students would read books, experiment, and exchange ideas; but we continually failed to translate our conclusions to the Jersey City environment. At the end of one bull session I remember Wally saying, "Why in hell should a kid who's growing up in this hole care about grammar or fractions or spelling? These kids need something for right now... They'll be interested in subjects that can offer them help and hope right at the present. .. Why should someone from this awesome ghetto listen to me tell them about Christopher Columbus? Nothin's more screwed up than that... These kids don't want to learn the traditional crap we're teaching them—because it's exactly that—crap. The modern school system is trying to reach children's minds by going through their assholes."

In light of these arguments, air pollution seemed to be the perfect topic for All Saints' sixth grade because, if Jersey City has anything, it has air pollution. As I outlined a syllabus for the term I became fascinated with the interlocking knowledge of man. Percentages describe the content of the air; molecules and atoms interact to create the chemistry of pollutants. Organisms react to pollution according to biological laws while the chemistry of burning explains how more pollutants are formed. High in my ivory tower I also contemplated the geographical and meteorological conditions which affect air pollution and dabbled with the percentages and fractions of different pollutants in the atmosphere. Like one long, intricate, marvelous chain each subtopic seemed to lead to a new branch of science. I was positive that every student would be captivated by this web of scientific knowledge, but not even one shared my fascination. Soon it dawned on me that they did not have the background for such comparisons, and furthermore I only lectured at them. They squirmed in their seats or ran around the room but did not join in.

Desperately I searched for some way to get them involved. The school owned no scientific equipment; my room did not have a sink or even any matches. I attempted a few makeshift demonstrations with scrounged-up materials. Once I burned some sulphur on a pie plate to give the kids an idea of what raw sulphur smelled like; that at least brought some realism into the discussion. Mostly I resorted to my notes—occasionally using filmstrips when I could get them. Nights passed in frustration—correcting flunked exams and wondering how to enliven my class with the facilities available. I thought of starting a new unit but bravely decided to struggle on until we finished. Meanwhile the final class bell ending school for the day brought cheers. The children scampered out of the building while I changed uniforms from teacher to coach.

In many ways the youth culture of Jersey City seemed to center on basketball. Acres of tar plus a cheap ball equaled a dribbling staccato that echoed across Lafayette. Local kids welcomed "hoop heroes" and promptly deified the Knicks when they won the world championship that spring. I had played basketball in high school so I organized games for All Saints' students two or three afternoons a week. Occasional- ly there would be a host of kids; other times only a couple would show. Gradually I began to notice that two distinct groups of players would form. The white kids self-consciously kept to one corner while the black kids hammed it up trying to show off their moves.

The same division materialized when I would visit Lafayette Park on weekends. White generally kept to white, and black to black. Most of the time very few white kids would even come close to the park, and I would be the only Caucasian on the tar court. It struck me that neither race felt comfortable in the other's presence. Somehow these human beings were taught the unnatural suspicions they held. Why do two groups of people, who have so much in common on the same sinking ship, fail to identify with each other?

One Saturday I met a white sophomore from Lincoln High School who was playing basketball at Lafayette Park. Of medium height and heavy set, Hal explained his attitudes towards different people to me. Although we had just finished playing with several black teenagers, he said that he disliked all the "coons" because they could not be trusted. When I objected to his generalizations, Hal very patiently told me that the "coons" tore down baskets and stole the nets. Running into a blank wall, I asked about other facets of Jersey City. His career plans were "to get a job in a gas station someplace." Just before we parted I inquired whether he planned to stay in Jersey City when he graduated from high school. With a surprised look he turned and said, "Man, I'm gonna get so far away from this place ... and then I'm gonna forget how to come back."

My sneakers noiselessly met the sidewalk on the way back to the house, and I dribbled the ball in the halting pattern of my thoughts. I failed to understand why attitudes hardened so viciously—why Hal refused to look at blacks as people and denied them a mandate in America's growth. Maybe I was naive to suddenly recognize a conflict that sociologists and bureaucrats had debated for so many years. The question of race pervaded American culture to such an extent that I assumed I was well-versed on the subject. Yet all my spurious arguments collapsed beneath the onslaught of reality, and suddenly my mind stood naked before the frigid rationale of prejudice.

ADULT EDUCATION COURSE—(noun; orig.—urban American) a program of night classes designed to teach interested adults irrelevant material; in successful cases this program culminates with the presentation of the High School Equivalency Diploma.

Don Farley drafted five interns for the AEC offered at All Saints School during that spring. At first we only reluctantly agreed to spend our evenings working with these adults who had dropped out of school. However, it was really pleasurable to find Jersey Cityites who wanted to open their minds to new ideas. After struggling with the kids all day, a teacher honestly enjoys students who motivate themselves. I derived much satisfaction from tutoring Mrs. Burns and George Cavett, although we did not come close to finishing the required work. In any case, the significance of the course only drained out to diploma-waving.

Most adults in the AEC work for their diploma either to satisfy a job requirement, like George Cavett, or to simply enjoy the personal accomplishment of getting the certificate, like Mrs. Burns. In both cases the students graduate with false knowledge. George had no need for grammar as a construction worker, but he had to learn it in order to be promoted. The diploma becomes the key that unlocks certain doors to jobs, positions, and prestige. Rarely does anyone ask about the meaning behind the certificate. What kind of learning does this diploma represent? Can the graduate apply those facts to his life and work? Will this diploma bring him insight into his own life?

Not that Mrs. Burns and George should not feel proud if they ever earn their certificates. In a society that labels eddicated people smart and uneddicated people dumb they should relish their graduation. Mrs. Burns and George always heard that intelligence grows in school—like a weed.

With this motivation, the 40-year-old black woman and 23-year-old black man opened their minds for me to cram in all the facts that I had memorized during high school so they could pass the exam to get the diploma to show their friends who would then know that they were smart. Although I had misgivings about feeding them what appeared to be pablum, I complied. After a few weeks George could take no more of it, not to his discredit, and no longer came to class. On the other hand Mrs. Burns remained undiscourageable.

She had a third-grade reading level and very little understanding of the world around her. Frankly, Mrs. Burns consistently floored me with her ignorance. How could a 40-year-old American citizen avoid knowing who Christopher Columbus was?

We worked with long division and multiplication at the outset. She understood these procedures but drowned in fractions and decimals. I found it hard to believe that she could have shopped for so long but did not know how to compute the price of a quarter pound of cheese at 89 cents per pound. The local shopkeepers must have loved to see her coming. On alternate days we used a reader to develop vocabulary and comprehension. I went to my wits' end trying to find something suitable to read. Obviously I could not insult her with children's books. However, she could not even follow special adult books written for non-readers because she was unable to assimilate the concepts.

One night far into the term, Mrs. Burns stunned me by saying that she had no idea what a microscope was or what a telescope was. I tried to contain my surprise, but after she left, sadness consumed me. Mrs. Burns had lived for years unable to appreciate two important spheres of her environment.

Imagine the tiny but vital world of the microscope with its countless organisms which shape our lives. Picture the vast world of the telescope spanning the heavens as man shrinks to insignificance in its expanse. Now estimate the daily satisfaction one receives from knowing these two worlds exist. Think how much more life can be appreciated simply by recognizing these two dimensions as parts of a boundless universe. Lastly, try to envision how stark and limited life would seem if one had no knowledge that galaxies and microorganisms existed. Such was the view of Mrs. Gloria Burns. In the harsh reality of that ignorance, I did not know where to begin. How to build a house without a foundation in too little time?

Once again the children seemed to be the only hope to reverse the trend, and they staunchly refused to think. I kept asking for new ideas on book reports, but my Group 4 Reading class fed me the same Jack-and-Jill garbage that had worked for so many years:

Mama's Bank Account May 2, 1970

Patricia Logan Reading Class

This book was about these people who had lots of problems so they moved to this big apartment house and they didn't have to pay rent because the owner said they didn't have to pay because they solved a problem of the owners. And they were good friends. I like the book because it was interesting.

I kept writing big C's and D's on top of the papers and passing them back—always hoping and waiting for next time. Unfortunately I had no better system of discipline either.

Every Tuesday when I was in charge of All Saints' detention class the same questions raised their ugly heads. Is detention class necessary? Why keep a kid after school when the only result is wasted time? Does it build needless resentment? Is it better to sock a student the first time he acts up or try to reason with him? As the chastised troops ambled into the detention classroom my spiel went like this:

"All right, get in your seats!... Everybody take a seat and make it snappy!... Hey you! Leave her alone and get in your seat!... I said 'Sit down!' Now sit!... What are you doing in here if you don't have detention?... Well, wait for her outside! Get out! Get out! Out! Out! Out! Out!...

Everybody take your paper and pencils and copy these three sentences, twenty-five times each... Put your hands down until I've finished talking. I'll answer your questions then... Johnson! Get in your seat and stay there!... What do you mean you don't have any paper or anything to write with? I don't care if somebody stole it; you could have gotten more paper before you got in here. Go down and see Sister Carolyn... Anybody else got any problems?... Be quiet and keep writing... Quit yelling!... Don't throw that pencil at her! All right you have detention tomorrow night too..."

And the beat goes on and on and on.

It was all pretty brutal on teachers and students. By 3:30 p.m. nobody feels like cooperating, and I sympathized with both groups because I was both All Saints teacher and Dartmouth student at the same time. Many hours I sat at the teacher's desk watching everyone copy furiously—and wondered how things had worked out this way. What sadistic monarch imposed the system on us all? The students were alienated more than ever. They nurtured resentment and contempt both for the school and its system.

I desperately wished to open. myself to those kids and explain that no animosity was intended. I wanted to prove that we could work together and accomplish great things The message always transmitted poorly, and we faced each other at opposite poles. Detention identified the teacher as the common enemy. Constantly I endeavored to bridge the student-teacher chasm. Idealistically I had hoped to ignore the authority one assumes with the title "teacher." For a few weeks my science class thrilled at the few restrictions I would or could impose on them. Eventually my patience ran dry, however. I must confess to the rest of my generation, those in school and out, that one day I found that a dose of hard-nosed, old-fashioned discipline solves the problem very neatly.

Earl Fleming caused more and more trouble as the term progressed. Gradually he jeopardized my control of the entire sixth-grade science class; and after a great many reprimands, I entered class one day in early May bent on asserting myself.

As usual Earl began wandering around the room, and things became heated when I told him to sit down. Finally he wandered by my desk and muttered a little: "I'll sit down when I'm ready to." That did it.

I dove after him and literally carried him to his seat on the other side of the room. We knocked through a couple of rows of desks on the way over; the room turned deathly quiet as I plopped him in his seat. A passing teacher took Earl out of the room while I turned to warn the rest of the class against future disturbances in my loudest roar:

"How long did you think you could get away with all the backtalk and other foolishness? I came to this school expecting to treat you like mature sixth-graders, not like little third-graders who have to be watched all the time! When I first came here to teach I promised myself that I wouldn't touch any of my students. But I guess I'll just have to break that promise. If I have to sit someone down to keep them quiet, then I'll just sit them down! I want everyone in this class to straighten up or you'll all be in big trouble. That goes for everyone—Aaron, Paul, Peter, Roger—don't test me or you'll get it worse than Earl did. I'm done fooling around with you kids..."

I was really worked up and actually screamed at them; they filed out quietly on the bell when I finished my tirade. I began to have serious misgiving about the whole incident after it was over; yet the situation improved. In the next two weeks we accomplished miracles as far as schoolwork was concerned. Even so, I could never completely justify that Physical and emotional outburst. While strengthening my authority irreparable harm was done to us on a personal level. It seems we never gave each other a chance as people. After the last exam on air pollution the whole class breathed a unified, polluted sign of relief. Despite our three reviews of all the test questions and answers, about one third of the class flunked. Relentlessly I spurred them on. They needed a personal project to capture their interest.

Careful thought produced a brainstorm—each student would grow his own tomato plant in a small cup and keep a journal! Naturally they would all take interest in their own plants; furthermore, only seeds, water, styrofoam cups, and dirt were required. I gathered the first three ingredients for the next class—only the dirt had to be procured. Where was the best place, other than City Hall, to get good dirt in Lafayette?... Lafayette Park, of course! I planned a field trip based on the premise that it was easier to lead my class to Lafayette Park than to bring Lafayette Park to my class. The reader may refute the credibility of that supposition in view of what followed.

First of all I needed another teacher to accompany me and help control the 32 little cherubs. But by this time my science class was notorious, so it was no easy task convincing Tom Sirota to aid my cause. Luckily, in a weak moment he agreed to help chaperone. The following day I issued cups, tomato seeds, and a stern order to behave; and all 38 of us stampeded down the stairs and out of All Saints School.

I intended the whole project to involve the kids and hopefully stimulate their interest. Without a doubt everyone immersed himself in the dirt-gathering phase of the project. They gathered it, threw it, scraped it, threw it, ate it, threw it, stomped it, threw it, and loved every minute of it. I hollered myself hoarse while Tom patiently tried to stem the scuffles that developed. Eventually we gathered a quorum together and headed back to the school. Some ran; others walked; a few straggled. We ended up strung out a quarter mile between the school and the park. I finally returned with about 25 of the original 32 students; science was the last period of the day so some had just slipped away. As we climbed the stairs Sister Carolyn stood outside her office giving the administrator's evil eye. However, I really think she condoned the project; she just had envisioned a more orderly enactment. So had I.

The following day we finished the planting operation. However, about ten students had either (a) lost their cup and its contents; (b) had it tipped over; (c) had it stolen; (d) seen it fall out the window while pulled by some mysterious force unknown to them. A curious scraping noise underfoot revealed the resting place of some of the dirt, and even more found its way out the windows and down to the pavement three floors below. In response, I doubled up students and ordered each of them to keep a journal on the same plant. Weeks went by and most plants sprouted under the watchful eyes of the future scientists. Each day entries were made in notebook journals while we studied photosynthesis in class.

My whole idea centered on involvement. I felt that this class especially needed to identify with some phase of science to create genuine interest—regardless of what phase it was. The project succeeded in that respect. Proudly students showed me their first sprouts and measured them for their journals. Others who had no positive results looked on jealously. (Later studies proved that most of these kids had forgotten to put a seed in to begin with.) At the same time I explained how the small plant began to grow and reach for sunlight. I attempted to apply scientific facts to the personal project they had before them. Lectures during the first half of the term were projected at the kids, not planned with them. Since few had any first-hand experience with scientific procedure or data, they were hopelessly lost. But now as they cultivated their very own plant, I cultivated an interest in botany.

One can never know who or how many students were turned on. I like to think that a few became mildly interested anyway. My test results proved little because no trends developed; many still flunked. At least no one got worse. On the other hand I saw new sparks of interest from many, and several of the plant journals had rather personal entries. Ernie Masters undoubtedly identified with his plant. The final entry read:

May 27, 1970

1. I axidentally pulled my plant out

2. I replanted my plant

3. I watered it

4. I think it will die

5. It fell out again

6. I replanted it again

7. It fell out again

8. I replanted it again. But I think its dead

9. It might grow again

10. Not a year old and its DEAD.

Pray for it. Say one Hail Mary, One Father Creed, and the Mass.

As Ernie's instructor it behooves me to point out that his other entries were a bit more scientific.

Marked by such victories and worse defeats the term progressed, and gradually I learned more and more about the citizens of Lafayette. Occasionally parents dropped in after school to speak to a teacher, and the interns gained a better understanding of city life through these visits. Halfway through May the father of one of my students came to the school for a conference and stunned me by asking, "Why in hell did you come down to a dump like this from New Hampshire?... I mean it must be real nice where you live in the suburbs... Christ, I been trying to get outta this mess for years, but just can't afford it... You're just lucky you don't live here."

Nearly speechless, I could only mumble some polite reply. Without qualification this father and husband told me that he and his family lived in a dump. His life oozed onward with no way out of the ghetto; he had surrendered to the filth around him. Seeds of revolution sprout here.

Like hot tar the atmosphere entangles human beings and restricts their hopes and dreams and movement. At night children call to each other in the street below my window. The sounds of running feet on pavement, faroff bark of dogs, and passing cars mix with the young voices. In the distance breaking glass and screeching tires occasionally reach the ear. The still air folds like a dark blanket across the city; the humid blackness of the spring night dulls the senses, then the mind. Night closes in, but the children play beneath the street lights. School slips from memory; youths gather on the sidewalk. Exhaust fumes linger in the air. God what rot is this? An eternal grave for kids who will not flee. Why should I help them? Is it for my own satisfaction? Will they be my friends if I try to assist them? Yet they have bitten the hand that I offer to help. I suppose they cannot tell the difference between the hand that reaches out to help and the hand that reaches out to push them further down. Somehow ignorance has led them to this degradation. Ignorance succored in this ghetto. And ignorance cannot be overcome without education.

This ultimatum always reinforced my fervor as a tutor That in turn bolstered my idealism because I always found basic goodness in every child as an individual. Diego particularly revealed all his problems to me without hesitation. Even as May slid by, he still failed to associate letter groupings with sounds. I would present a list of words like pop, mop' hop' cop, top and read the first our words as he repeated them. Then I asked him to read the final word, and nine times out of ten he would say something like "tin" Instead of "top." Pure frustration. No reinforcement at home. How could we pass this joyful mountain of blubber into the fourth grade? At night I contrasted the sight-word approach to reading versus the phonics system. Books by Sylvia Ashton Warner and Rudolph Flesch convinced me first one way and then the other. In either case I would always walk into school the next day armed with an ironclad theory and stacks of confidence—only to run smack into Diego and the human element.

Finally, halfway through May, he finished Phonics Book A which dealt primarily with initial consonant sounds. Happiness bubbled out of the conference room. Diego was proud and pleased; I was proud and pleased; the whole world looked rosy and joyful. I took him to Sister Carolyn, and she patted him on the back while he beamed gigantically. Then I presented him with a candy bar and sent him back to class with the assurance that he could do anything he set his mind on. The praise and encouragement brightened Diego's day immeasurably, although he still did not make the connection between words and sounds. The following day he continued to guess at things he had just "learned"—but he was infinitely lovable. I know he tried terribly hard, and I wanted to reward him for his efforts. He needed only one key to make everything fit together, but I failed to help him find it.

These practical situations always seemed to contradict learning theories and education books. .Most of the experts called for elimination of punishment, discipline, classrooms, and structured curriculum. They advocated free wheeling programs where students could choose to study whatever interested them. Furthermore these men believe that a child's natural curiosity will lead him to a well balanced program in the end. Ultimately, the distasteful and oppressive dominance of the instructor will have been avoided.

The more I attempted to institute these ideas, the more harried and frustrated I became. Nothing worked out. The idealism broke down. I decided that either the students at All Saints had not read the books or the theories did not apply to real students in real schools. Anyway, the damn books did not aid my cause one iota, and similar experiences convinced me that the "ideal learning environment" was a hoax. I had just finished painting mustaches on all of these villainous authors when the Dartmouth students visited a teacher's heaven...

May 10, 1970

Journal; today Ken, Tom, Barbara, Wally, and I went to the Children's Center in Tenafly, New Jersey. What a gorgeous, beautiful, mindblowing school! I felt uplifted... All the theories of abstract education have been applied to this institution, and they work. They really work!

About 75 students, aged 2 to 11, have been divided into three different levels in separate rooms. The children have a fantastic variety of modern facilities available to them, and they can choose to participate in anything they wish during the day. A photography dark room, complete wood-working shop, kitchen, and conference room all complement the three colorful meeting rooms.

We spent most of the time watching in fascination at the youngest "class" aged 2 to 5. These traditionally preschoolers choose from painting, claywork, cooking, blocks, tumbling, board games, flashcards, magnets, scales, crayons, rulers, a talking typewriter, and literally hundreds of other diversions. Each child plays with whatever intrigues him and picks something new whenever he loses interest. For this reason the kids always participate and learn. Their interest never lags since they personally decide on the medium they wish to work with. These youngsters cannot help assimilating new ideas.

I helped a cute, brown-eyed little lass into a painting smock, and she pointed out a bean plant that she had planted in a foil pot. The name she had written on it was SUZANNE. I remarked on the name tag and asked Suzanne if that was her name. She replied, "Yes, that's right... I'm three years old. And you know what?... My name has a silent "E" at the end."

I almost fell over when she came out with that. Think of Diego struggling with word sounds at age ten. How could I explain the idea of silent vowel to him? What a hugh difference environment makes!

Inevitably we returned to Jersey City and another world in a different universe. Green countryside, fresh paint, carpeting, air conditioning, spacious rooms, and attractive furnishings have vanished. Wally, Ken, and I just bulled for an hour about the trip while Tom corrected test papers. We imagined different ways to transform All Saints School into a Children's Center. Then Tom jolted us back to reality. Shaking with laughter he handed round one of his test papers. Each student in the fifth-grade math class had been assigned to write a math problem using fractions. The offering of one little girl read:

If Mark has 2 3/4 poke chops and Judy has 12/3 chicks, how many chicks do you have?

Answer: 2 3/4 - 1 2/3 = 2 chicks.

A few weeks later the nuns treated the graduating eighth-grade class to a class trip at the Jersey shore. This consisted of an entire weekend at the Sisters' summer retreat with the teachers along as chaperones. For three glorious days we washed Jersey City out of our souls—wonderful! Ironically the kids revealed both massive ignorance and awesome maturity at the same time.

Again and again these children demonstrated complete naivety about new environments like the sea. They told Sister Mary Ann that they would be bored at the beach because there were no stores around so there would be nothing to buy and therefore nothing to do. She could not convince them that they would discover new interests at the ocean.... Take plankton as an example. We walked the beach at night and the phosphorescent plankton twinkled at our feet. At first the eighth-graders stared in amazement. After I explained that plankton were microscopic sea animals they all left the beach rather frightened. Neither my entreaties nor explanations could allay their fears. Their understanding reached no farther than the urban background, and that environment prompted no desire to examine the rest of the world. In their city element the kids boisterously acted like kings, but we saw them as children when they ventured beyond that setting. How can anyone really be alive if he is not stimulated by the thought of a new environment?

On the other hand, these young men and women held no reservations about drugs, alcohol, or sex—and all were readily available. The eighth-graders spent Saturday night getting royally drunk. These urbanites had long dedicated weekends to a total physical and psychological release from the grime of the week's routine. Several members of the class, both white and black, just drank and fornicated until the "children's curfew" at 1:00 a.m. Later I learned of the night's activities from one of my young friends; the nuns never realized it. The kids wanted it kept that way because they respected and loved the Sisters, although they could not do the same for themselves.

The next afternoon we rode back to our monolithic home. No miracle cleaned the streets in our absence; no friendly zephyr freshened the air. Some youngsters played in a spouting hydrant at the corner of Lafeyette and Whiton Streets. Water gushed across the intersection as children screamed delightedly; however, all neighborhood faucets bled orange as rust shook loose in the pipes. Eventually a cruiser passed. Two policemen terminated the water ballet, and the children retreated to the shade of nearby porches. After a warm humid night the inevitable school bell rang once again. The old conflicts rekindled.

Charlie Gotham refused to quiet down in science class. After I told him to stay after school he spat an obscenity at me. When I sent him down to see Sister Carolyn he left—while threatening to punch me in the nose as he walked out. Hovering between indignation and contempt I had to choose whether to ignore the incident or take immediate action. Since the rest of the class waited for my response, I had to assert myself or lose control forever. I grabbed Charlie's arms and shirt and dragged him out of the classroom and down three flights of stairs to the principal's office. Sister Carolyn heard me out and then lit into Charlie with a list of rhetorical questions. She literally cut him to pieces emotionally and psychologically. Soon he broke down in tears of remorse, and I returned to class having eked out a narrow victory over the opposing forces. However, formidable opponents still lay ahead.

Charlie opened the door for other challengers. Roger Vernon and Peter Wallace began to disrupt the class, leave their seats, and walk out of the room without permission. Gradually I surrendered control of the class, and every student knew it and pushed me further. I recognized that the best way out to correct the situation was to rap someone in the head in full view of the class. Yet I hesitated, for I had personal doubts about the discipline system and myself as a teacher.

If the students had learned to appreciate knowledge from the first grade, then the behavior problems would not have occurred. Actually it seemed ridiculous to have them listen to me; all I could do was feed them information. What good was that? Suddenly all my shortcomings stood out clearly; I had neither stimulated the class to think nor given them useful information for their daily lives. My facts on air pollution did not interest the kids. They probably considered it another Jersey City problem which could not be solved. Thus I really doubted my right to command their respect, for I felt I should earn their esteem as a teacher and not simply be granted it with the title. My curriculum was useless in its old state. I faced the challenge of reaching into their world to deal with their questions. Unfairly I wanted to blame the whole mess on All Saints School, but the hang-up lay elsewhere. These kids only adapted the home atmosphere thrust upon them. Dammit, school and learning should not lead to boredom! Somehow the plant projects had to work—if only the seedlings grew a little higher and a little faster I was sure the kids would be enthused. Consequently 1 waited and hoped—tolerating the classroom disturbances all the while. I determined to prove that learning can bring joy by making a human being proud of his intellect.

Unfortunately practicality, custom, and convention forced us to work through the age-old grading system. This reward and punishment scheme defeated my whole purpose. How could I convince the kids to enjoy learning for its own sake when I dangled a grade over their heads at the same time? I tried to avoid it. Quite fittingly they reacted with contempt. In order to go to high school and get a job they knew they had to pass tests, not learn. As in almost all school systems the children worked to please me, not assimilate the material I offered. Every assignment evolved into an unpleasant task. All they understood was that I wanted a piece of paper covered with hieroglyphics; then I would get off their backs.

The students cheated and lied to me constantly. Homework assignments and test papers were exchanged freely; book reports were mass-produced. The students did not foresee the uselessness and self-hurt caused by these actions. Through written assignments I wanted them to become activated mentally and then to look beyond the limits of Jersey City. They failed to comprehend. The structured marking system encouraged this rampant dishonesty. No matter how many times I declared that true learning was the most important factor; the almighty grade still went down in the book. That tiny A, B, C, D, or F held ultimate power. It determined who failed and who passed, who rotted in school and who escaped, who went to high school, and who got a job. Small wonder that the kids preempted the grade in favor of learning.

I succumbed. I had no choice. In recognition of the need for A Final Grade I pushed the kids for marks. The end of May approached, and about half of the students in my, classes were flunking. In desperation I turned to that old insidious device-—the warning slip. I blew one Saturday night reviewing my rank book and made out 46 of the little demons for students to take home and have signed by their parents. I really did not anticipate much. In fact my pectations ranged from parental indifference to parental indifference. Uncertainly I waited for the returns.

At first the parental signatures only trickled back. The students tested the teacher's mettle. They refused to believe I was serious; most had never seen warning slips before. Then I gave out detention to the students who had not returned them. Finally, I made telephone calls to every parent that I had not heard from. The response stunned me.

Almost all parents expressed genuine regret and surprise at their child's performance. Most said they were very happy I called and spoke quite respectfully to me as Mr. Kimball even though I was young enough to be their son. Other parents called back to ask about incomplete assignments or failed exams. Several even wanted their child to do extra credit work. The entire mood of my classes changed. The clowns and jokers paid attention and took notes. Behavior improved. My ear hung limp from all the telephoning, but it brought dividends. Chastised siblings came to me rubbing their sore butts and asked me not to call their parents back. Others regretfully added that they lost a lot of their privileges. Actually I did not expect these urban parents to care that much about their children. Although many boozed away their wages and left their brood to fend for themselves, they still did not want their children to follow their footsteps. These adults hoped their children would have a new and better life. Thus they catered to my wishes because pleasing the teacher meant getting good marks and getting good marks meant getting an education and getting an education led to getting out of the city. To accomplish the end you work through the means because the instructor knew what he was doing...

Under the combined efforts of parents and students and teacher the grades climbed. Everyone marveled at the advancement in learning except me... teaching can get you down.

With increasing speed the final day of school drew closer. Failure alternated with success as I reviewed the term's work. Last-minute exams revealed great advances in some areas matched by hopeless downfalls in others. I cannot forget my disappointment at receiving an armful of horrendous geography reports on the final day of class. I felt defrauded of the entire term's work. Even my star pupils failed. Thomas Holmes, one of the top seventh-graders, submitted this as the fruit of a five-week assignment:

Modern France: An Industrial Nation Part I Natural Resources by Thomas Holmes Most of the bruetiful land in france lies in the Aquitaine Basin which is in the Southwest part offrance. It is an area of nearly level land generally useful soils, and a favorable climate. The food and other products grown there are very impotant in helping to support the nation. If it wan't for france we would be without many nessities as well as luxuries. The USA really does o france a great deal of thanks and gratitude. This is the economanal report of france. This has been a very short report I know. But I had some faulty information and that's why it wasn't done. I hope my friends will do better. I also hope I get a good mark even though I had a short report...

His teacher bestowed a bright red furious "D" at the top of the paper. The F's were reserved for those who did nothing.

One by one my classes met for the final time. The kids said goodbye, each in his own manner—some affectionately, some flippantly, but all with a touch of remorse that the students from dartmouthcollegeinnewhampshire would soon depart.

My concluding meetings as tutor were designed to blow the third-graders' minds. We looked at hair, insects, blood, saliva, and gutter water through a microscope. Diego, more than anyone else, found it impossible to believe that cells, protozoa, and bacteria actually exist. He kept exclaiming, "Is that really water?... Are those things really like that?... You gotta be kiddin' me, Mr. Kimball!... Do those things hurt you?" Inevitably the sideshow ended. We cleaned the slides together, unhooked the light source, and repacked the microscope. After he recited the alphabet one final time, I tenderly shook his small brown palm. As Diego turned to leave, I could only hope that his next teacher would forge the key to unlock his mind.

June 4, 1970

Wally had $7 stolen from his bureau drawer this afternoon. That brings the total of his term's losses to $22. Other thefts include: Ken, $10; Alex Meyers, $10 and a camera; Ralph Letner, a camera and his car; Cliff Brown, $20. We could use a security guard around here.