A museum guard is more than a watchdog. He is a keeper of grace.

MY FIRST JOB out of Dartmouth, in the bicentennial year of 1976, was as a guard in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I was part of the crew that guarded the Robert Lehman wing, one of many appendages the Met has grown in the past 20 years or so, this one offits Central Park side. When I started guarding Mr. Lehman's impressive collection, the wing was already several years old and had slipped into a kind of "attached studio" status. The traffic tended to be light, except, of course, on weekends, when the whole world seemed to visit the museum all at once.

The Lehman holdings, choice in all respects, were not difficult to get to know as a guard—intimately. Spending a long Tuesday morning in the same small, windowless room with Rembrandt's portrait of his syphilitic nephew, your mind sometimes gets to playing tricks on you. Just how long can you study that pocked face before the lips begin moving? And the dark velvet draperies that cover the walls—at what point might you start to climb them, making monkey noises?

Fortunately, the guards rarely spent two days running in the same spot. One morning I would be stationed near Balthus's portrait of a prepubescent girl; the next, exiled to the wing's lower level to keep an eye on the Seurat drawings and other light-sensitive works on paper.

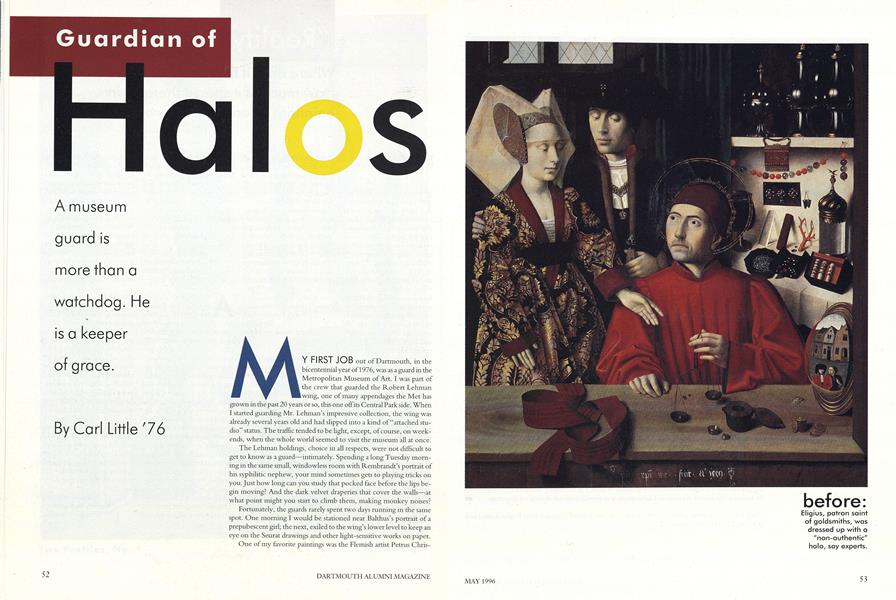

One of my favorite paintings was the Flemish artist Petrus Christus's Saint Eligius. This oil on oak from 1449 shows the patron saint of goldsmiths in his studio, with the tools of his trade close at hand. He is shown with a young couple, whom he is fitting with rings for their upcoming marriage.

What was so great about this portrait? For one, I liked the way the artist had incorporated the witnesses to the marriage via a convex mirror that reflected a man and a woman standing outside the window of the goldsmith's shop. And the cloth of the wife-to-be's outfit was so exactly rendered that it seemed to leap off the surface of the painting—a very modern touch, thought I, who had taken Introduction to Art History with John Wilmerding and Frank Robinson at Dartmouth.

And then there was the halo: The saint's head was ringed with two thin circles of gold, and there were short gilt rays radiating from his head—like the edges of a spider web highlighted by a beam of sun. The halo was modest, befitting a flesh-and-blood individual who had, through the skill of his hands and eye, managed to create jewelry that made him worthy of sainthood.

Imagine my regret and sorrow, then, to open an issue of the Metropolitan Museum's bulletin, devoted to conservation, to find that the saint's halo has been removed!

My first reaction to this desecration was a holdover from my training as a guard: Catch the bastard! Then I read the explanation: In preparation for a show of Christus's work, the conservators had chosen to remove this "non-authentic gilded" halo from the saint's head.

The reasons for the removal seemed sound. According to Hubert von Sonnenburg, the Sherman Fairchild Chairman on Paintings Conservation at the Met, such "pious additions from an fied period" could be looked upon as "attempts to give a religious character" to paintings originally conceived as secular. Furthermore, he stated, the presence of such halos prevented "a proper reading" of a painting's background. Who would dare argue with that?

Well, I'll give it a go. First off, Dr. von Sonnenburg, that skimpy halo around Saint Eligius's head hardly obscured any background detail. If anything, the perfect double rings, painted on as if with a compass, complemented the jewelry gleaming on the shelves behind the saint. And, Doc, what's wrong with a touch of piety to underscore the guy's superhuman skills?

Most of all, I want to take the conservators to task for not considering the mental equilibrium of the Lehman guards. What about the poor guy who has been watching over Saint Eligius for the past couple of years, who comes in one day and finds the halo gone? Think of him doing a doubletake before the painting, rubbing his eyes in disbelief, feeling responsible, but not telling his superior because he might get fired and not telling his wife because she might commit him. He stands muddled, scared, even sorrowful before the painting, needing comfort but finding none. There's nothing in his union contract to cover this kind of problem.

I sympathize with the guard, I call out to him that the halo did exist once, lending radiance to a common man. I say, "The halo was okay," as he stumbles bewildered from the room, thinking about applying to the Whitney or the Guggenheim if they'll have him.

And I offer a caution: Be warned, you removers of halos. Should those thread-thin lines of gold reappear one day, transforming a man back into a saint, don't ascribe it to some miracle, like a weeping portrait of the Virgin. Self-appointed guardian of halos, I'm the culprit. Good luck finding me: I'll be hiding in the woods of northern Maine, smiling to myselt, gold leaf dusting my fingertips.

before: Eligius, patron saint of goldsmiths, was dressed up with a "non-authentic" halo, say experts.

after: Restorers secularized the Saint, sacrificing his halo in the name of accuracy.

unspeci-Furthermore, he stated, the presence of such halosprevented "a proper reading" of a painting's background.Who would dare argue with that? Well, I'll give it a go.

CARL LITTLE is the author of Winslow Homer and the Sea, Edward Hopper's New England, and a bookof poems, 3,000 Dreams Explained.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

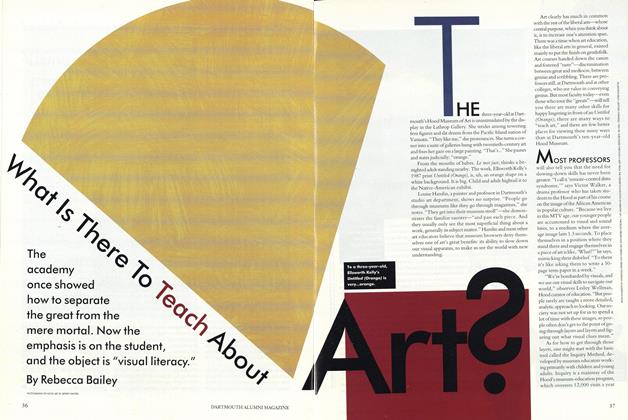

Cover Story

Cover StoryWha is There to Teach About Art?

May 1996 By Rebecca Bailey -

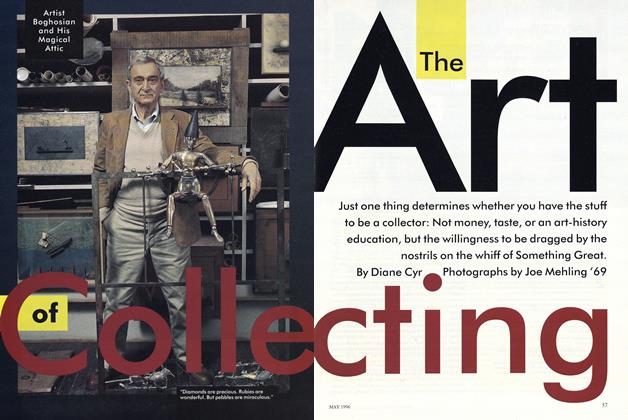

Feature

FeatureThe Art of Collecting

May 1996 By Diane Cyr -

Feature

FeatureA Mini-Seminar On Two Hood Pieces

May 1996 -

Feature

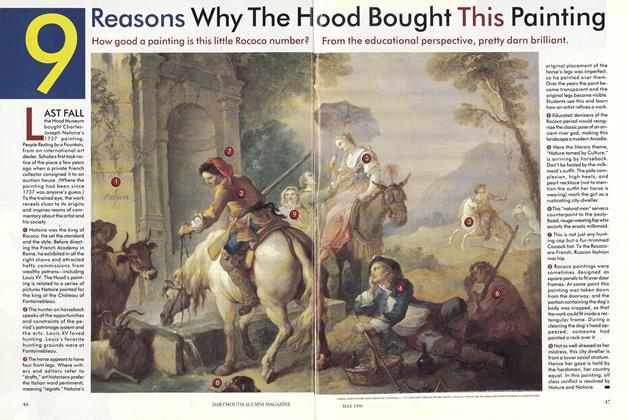

Feature9 Reasons Why the Hood Bought This Painting

May 1996 -

Article

ArticleVisions of the Ancestors

May 1996 By Karen Endicott -

Article

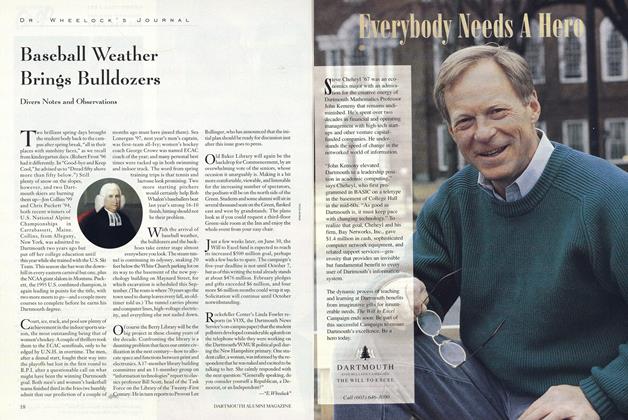

ArticleBaseball Weather Brings Bulldozers

May 1996 By "E. Wheelock"

Carl Little '76

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryMara Rudman '84

March 1993 -

Feature

FeatureSMITH

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Brad M. Hutensky '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWrong Scare

MARCH 1995 By David M. Shribman '76 -

Feature

FeatureNick Lowery '78 John Rassias

NOVEMBER 1991 By John Rassias -

Feature

FeatureTo Make What's Good Better

February 1951 By R. L. A. -

Feature

FeatureLAND OF LOVE

MAY 1973 By Ralph J. Fletcher '75