DEAR MR. MECKLIN:

Your letter in the October ALUMNI MAGAZINE has prompted me to break a long-standing policy of avoiding participation in the debates chronicled in that publication, as well as in my class newsletter (yes, I too am a graduate of the College). I have finally felt the need to plug in my typewriter and get it down on paper.

Your letter was well-written, kindly disposed to Mr. Cunningham, and seemingly well-documented. And, of course, it was polite and moderate ... above all, it was moderate. While I do not wish to develop extended arguments as to whether or not immoderation in speech or act is ever justified, I, for one, would assert that to ask a Vietnamese woman who sees her child napalmed to death to behave moderately is no more than a logical extension (a quantitative jump, not a qualitatively different proposition) of finding it worthwhile to comment, as you did, on the moderate way in which Mr. Cunningham expresses his views. It reminds me of the daily national perversity wherein body counts from Vietnam, both American and Asian, are reported in the same tone and voice that one relates the likelihood of rain. Spare me such an ethos. The detachment from the realities of existence which the confines of an academic or journalistic life affords has given you this ability, but it is by no means a luxury to be envied. Nor, as might theoretically be argued in defense, has it in your case (or does it normally) produce clearer thinking, more powerful insight, or yield more profound analysis and understanding of whatever is being investigated. Such might be the ideal of the social sciences, but as I will detail below, your letter, taken as an example, is no more than an eloquently stated solipsistic notion of how the world should be, created in America's image.

Taking your major points in order seems the most direct way. You say that the majority of Americans support Nixon's war, according to the polls. The polls gave Dewey a landslide, but the election went the other way. In 1968 the U. S. was given the sorry choice between Humphrey, a Johnson lackey who was feared could only continue the war, and a "new and improved" Nixon, polished for TV, with a "plan" to end the war he couldn't disclose for fear it would imperil the Paris peace talks (which talks he has ignored since taking office). It was a strange notion, a peace-keeping plan so profound it had to be kept secret or it would disturb chances for peace, but it sold. America gambled and the world lost. We now have his plan, an enlarged war, and the public will was rebutted. Polls?

May I quote you: "However repugnant the thought may be, the only peace the world has ever known has always been created by force, and weakness has always invited aggression." Morgenthau lives! But forgets that (1) force is quite different from violence and warfare, as attested by Gandhi's freeing India from Britain without a single act of violence or murder accompanying; and (2) India was and is a weak nation, and yet has to date been unaccepted in its invitation to aggression. More cases could be cited, but the point stands: did Hitler, your evil incarnate of the modern world, arise sui generis out of the benign context of Germany in the 30's, or did the forceful and violent treatment of Germany at the hands of the Allies in Versailles not forecast trouble? Violence breeds violence, hate is more easy to structure and live with than is justice, and it is far more profitable to those doing the structuring.

To say that "China fell to the Communists in one of the greatest disasters of our time is blatantly solipsistic and historically untenable. China didn't fall; she was raised up, literally by the much clichéd "people," fianlly tired of Chiang's warlords and the Big Four families, and the milking of China at the hands of the West, made "legal" by the Open Door Policy the United States sponsored. As Morgenthau himself affirms, this policy institutionalized "what you might call freedom of competition with regard to the exploitation of China."

The temptation to undertake a minute examination of the entire Vietnam issue is great, but I must defer to considerations of time and reading endurance. However, I can't overlook the following: Diem, your hero, was the most corrupt, fanatic, and, even to the social scientists we sent to advise him, irrational despot we have ever been burdened with supporting in Vietnam. He remained in power by brutally crushing all who weren't equally fanatic in his support, including neutralists and Buddhist factions, neither pro-Ho Chi-minh. Insisting on rigged elections so that he won not just a respectable fixed victory, but often over 100 percent of the votes cast, Diem headed, in the words of a Foreign Affairs article of January 1957, " ... a quasi-police state, characterized by arbitrary arrests and imprisonment, strict censorship of the press and the absence of an effective political opposition." And that was at the beginning of his regime, when things were going fairly well. The same statute which prohibits anyone in Vietnam now from advocating peace was operative in principle under Diem; the prison occupants were mostly those who wanted the Geneva Accords to be enforced — a hope Diem quelled on 16 July, 1954, when he flatly declared, following the conclusion of the Agreements, his intention to ignore them in both letter and spirit. The reprisals he carried out against the moderates in his country did more to alienate him and his government from popular support than could any foreign influence or aggression, excepting possibly what the 60's saw visited upon Vietnam by the U. S. Diem ruled more cruelly than had the French before Geneva. "The bulk of the population lived near starvation level, and the allied problems of landlordism and agrarian reform could not be seriously dealt with by a government fearful lest its wealthy elite would turn against it." (This from moderate British historian DGE Hall). The above took place, not coincidentally, during a period of massive U. S. aid to Diem, all of which went to arm him for the coming battle against his own people; and it can only be added that the NLF didn't form until late in 1960, and that the reasons for this coalition to liberate Vietnam need be - documented no further here. All that might be asked is why you so strongly laud our support of this regime?

For a discussion of your question about chances to get out of the war, and the way they were resolved, see Politics of Escalation, by Schurmann, Scott, and Zelnick. I would myself prefer to focus upon the Tonkin Incidents (produced and directed by the U. S., much as Japan fabricated the Mukden incident a generation earlier); the claim that SEATO obligations demanded entry as active participant, despite the fact that Vietnam is not a signatory to that pact; and the form our "response" took; to wit, massive air strikes against non-military targets in another country. Does this logic not give the Viet Cong license to destroy power plants in Ohio? I would also like to deal with the Geneva talks themselves, how we behaved at them, and our entry into the war which you mentioned not once. What of Admiral Leahy's mission to Vichy France in 1942, carrying Roosevelt's message that after the War, Indochina would either be Japan's or it would be the U. S.'s? (See Fall, LastReflections on a War, Page 125). How about Eisenhower's assertion that if free elections had been held in 1956, Ho Chiminh would have received at least 80% of the vote?

Your selection of evidence, therefore, reflects more than the discrimination which brevity and conciseness necessitate. You try to prove America's failure in Vietnam, but in awkward ways. The failure in Vietnam was not the confounding of the fiercest military machine ever devised, against peasants with rakes; of a $30-billion-a-year budget fizzling out against a rice economy of late neolithic techniques: America's failure is rather the predominance of ivory-tower intellects who can sincerely write about the slaughter of a million human beings and label it "the inability of the world's most powerful nation to establish order among 15 million peasants." Establish order — what the hell does that mean? Hitler used the same rationale in moving against Poland. Who gave us the right to establish order? Vietnam is not a chessboard for our will to manipulate enpassant; not a sealed laboratory for perverse theories of counter-insurgency and social engineering. It is a strong nation, its citizens justifiably proud of a more civilized people (though with fewer electric toothbrushes) and a great arid rich culture. Why are we vivisecting this country?

A few closing remarks: the Viet Cong and Hanoi are by no means indistinguishable, but are two entities, one in control of a state, the other in control of part of a state (estimates now run to 2/3). As for your description of the Viet Cong, several problems develop. If they have no support in the country except that wrought by terror, how do you explain the extensive reports to the contrary by independent journalists, such as Honda Katsuichi, who have visited liberated areas of Vietnam; of Jacques Decornoy, who writes extensively in LeMonde about the Pathetlao support in Laos, having visited these areas last spring?

As for a picture of China, Hunter's BrainWashing in Red China which you recommend is weak compared with Governor Romney's revelations about American methods. Hinton's Fanshen or any of Edgar Snow's work on China is more factual. In short, the "efficient subjugation of the human mind" of which you speak sounds more like Samuel Huntington's proposals, now being carried out, for treating the Vietnamese we relocate in "detention camps" throughout the countryside; nor, in fact, does it seem inconsistent with the unthinking acquiesence to official policy which people who should know better try to fabricate into excuses for our behavior in Asia.

Finally, Mao and Giap didn't create "new forms of warfare" as you posit. A look at the American suppression of the Philippines' struggle for freedom in the first years of this century, well documented in Senate hearings on the subject, reveals an encounter with remarkable new methods of warfare. Peasant populations, resenting a foreign invading force, secreted the insurgents among themselves, supplied, fed, and informed them of the enemy's activity, and almost ensured success. Almost, for the story of our military conduct in Vietnam was prefigured in the behavior of Arthur MacArthur, who led the fight against the Filipinos. Son Douglas couldn't help being impressed by a father who burned down villages at night while their inhabitants slept, and his subsequent comment, during World War 11, about his desire to kick a pregnant Japanese woman in the stomach should they meet, is a link between Luzon and My Lai. Our treatment of Asians has consistently been indefensible from any ethical stance, and therefore ironically dysfunctional even to our expediential, self-serving aims in the area. Could we have dropped nuclear weapons on Germany? Napalmed Naples? Never! Italians and Germans weren't locked up in concentration camps during the war in California; Japanese were. "It became necessary to destroy the town in order to save it" (quoted from an American major in a fight to take Ben Tre in Vietnam, 1968) means the Asians can be destroyed so we can save the town and then control what ultimately we value more than the people, their property, albeit in smoldering ruin. Are Asians different from us? We answered that years ago, by claiming to be Great White Father, never brother, whenever we encountered new cultures; from Indians to Cambodians. In your own Mission in Torment (page 76) you allege that the Vietnamese peasant is a man whose "vocabulary is limited to a few hundred words," whose "power of reason ... develops only slightly beyond the level of an American six-year old," and whose "mind is untrained and therefore atrophies."

And what we want from this undeveloped child remains a force today as it was when Dewey left San Francisco in 1898, before war had been declared with Spain, with orders to take Manila. But this time we are losing; and perhaps in time we'll have something to believe in again, something more than the rhetoric of apologists.

Mr. Hart is a graduate student at theUniversity of California at Berkeley, specializing in Chinese history and working for adegree in the Asian Studies Program. He isalso a member of the Bay Area Institute inSan Francisco and works with its PacificNews Service, set up last summer by agroup of journalists and Asia specialists asan outlet for independent reporting on thePacific.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

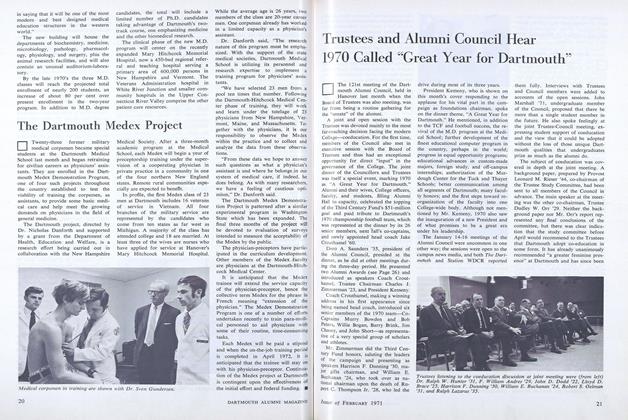

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Hear 1970 Called "Great Year for Dartmouth"

February 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThe Blackman Era: Sixteen Special Years

February 1971 By JACK DE GANGE -

Feature

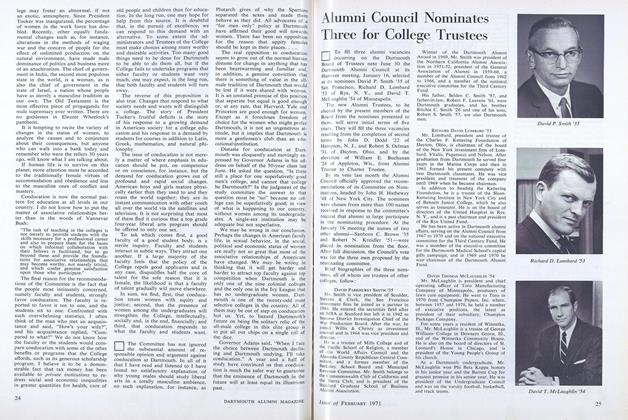

FeatureAlumni Council Nominates Three for College Trustees

February 1971 -

Feature

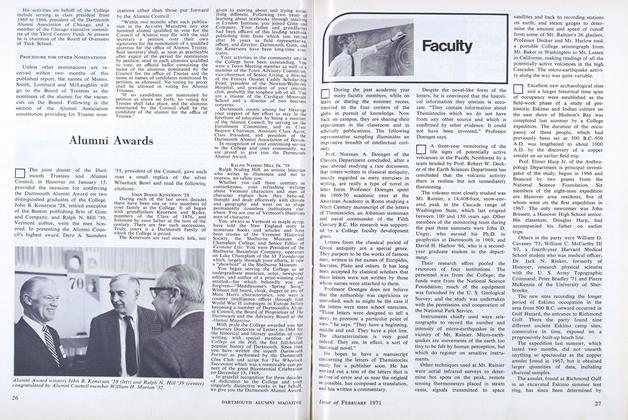

FeatureAlumni Awards

February 1971 -

Article

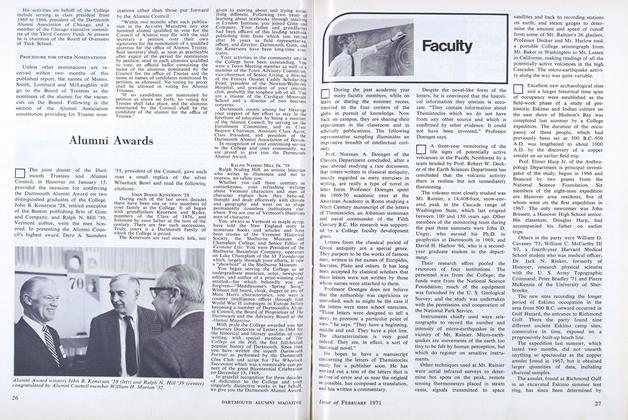

ArticleFaculty

February 1971 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

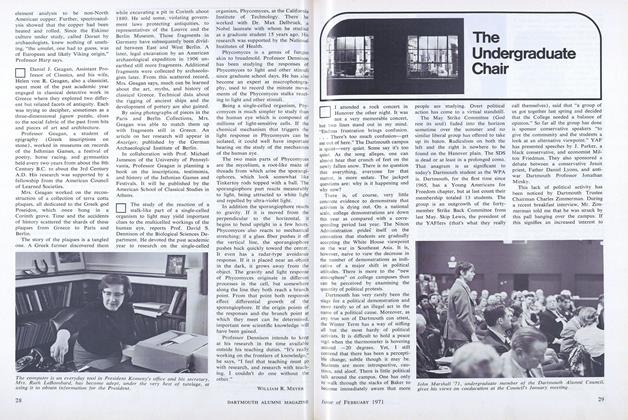

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1971 By STEPHEN K. ZRIKE '71