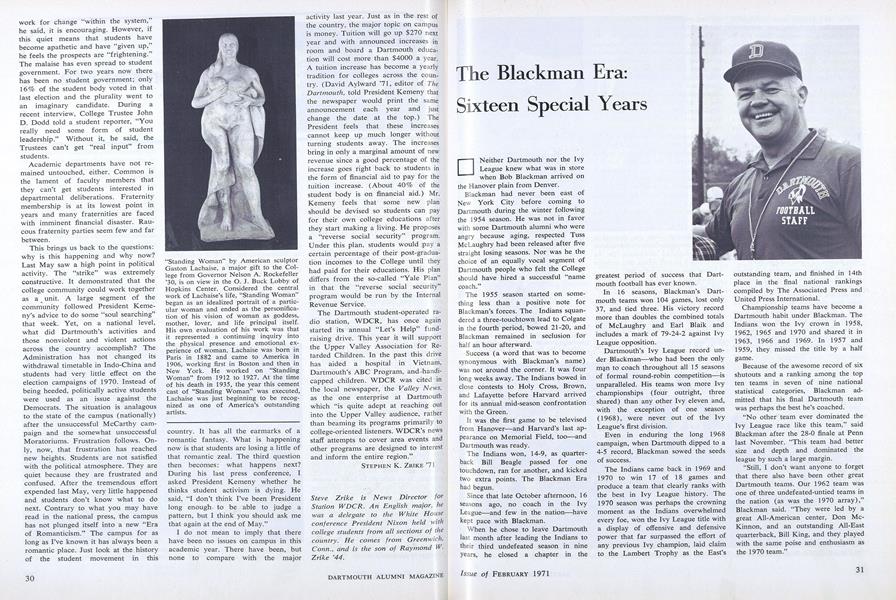

Neither Dartmouth nor the Ivy League knew what was in store when Bob Blackman arrived on the Hanover plain from Denver.

Blackman had never been east of New York City before coming to Dartmouth during the winter following the 1954 season. He was not in favor with some Dartmouth alumni who were angry because aging, respected Tuss McLaughry had been released after five straight losing seasons. Nor was he the choice of an equally vocal segment of Dartmouth people who felt the College should have hired a successful "name coach."

The 1955 season started on something less than a positive note for Blackman's forces. The Indians squandered a three-touchtown lead to Colgate in the fourth period, bowed 21-20, and Blackman remained in seclusion for half an hour afterward.

Success (a word that was to become synonymous with Blackman's name) was not around the corner. It was four long weeks away. The Indians bowed in close contests to Holy Cross, Brown, and Lafayette before Harvard arrived for its annual mid-season confrontation with the Green.

It was the first game to be televised from Hanover — and Harvard's last appearance on Memorial Field, too—and Dartmouth was ready.

The Indians won, 14-9, as quarter- back Bill Beagle passed for one touchdown, ran for another, and kicked two extra points. The Blackman Era had begun.

Since that late October afternoon, 16 seasons ago, no coach in the Ivy League—and few in the nation—have kept pace with Blackman.

When he chose to leave Dartmouth last month after leading the Indians to their third undefeated season in nine years, he closed a chapter in the greatest period of success that Dartmouth football has ever known.

In 16 seasons, Blackman's Dartmouth teams won 104 games, lost only 37, and tied three. His victory record more than doubles the combined totals of McLaughry and Earl Blaik and includes a mark of 79-24-2 against Ivy League opposition.

Dartmouth's Ivy League record under Blackman — who had been the only man to coach throughout all 15 seasons of formal round-robin competition — is unparalleled. His teams won more Ivy championships (four outright, three shared) than any other Ivy eleven and, with the exception of one season (1968), were never out of the Ivy League's first division.

Even in enduring the long 1968 campaign, when Dartmouth dipped to a 4-5 record, Blackman sowed the seeds of success.

The Indians came back in 1969 and 1970 to win 17 of 18 games and produce a team that clearly ranks with the best in Ivy League history. The 1970 season was perhaps the crowning moment as the Indians overwhelmed every foe, won the Ivy League title with a display of offensive and defensive power that far surpassed the effort of any previous Ivy champion, laid claim to the Lambert Trophy as the East's outstanding team, and finished in 14th place in the final national rankings compiled by The Associated Press and United Press International.

Championship teams have become a Dartmouth habit under Blackman. The Indians won the Ivy crown in 1958, 1962, 1965 and 1970 and shared it in 1963, 1966 and 1969. In 1957 and 1959, they missed the title by a half game.

Because of the awesome record of six shutouts and a ranking among the top ten teams in seven of nine national statistical categories, Blackman admitted that his final Dartmouth team was perhaps the best he's coached.

"No other team ever dominated the Ivy League race like this team," said Blackman after the 28-0 finale at Penn last November. "This team had better size and depth and dominated the league by such a large margin.

"Still, I don't want anyone to forget that there also have been other great Dartmouth teams. Our 1962 team was one of three undefeated-untied teams in the nation (as was the 1970 array)," Blackman said. "They were led by a great All-American center, Don McKinnon, and an outstanding All-East quarterback, Bill King, and they played with the same poise and enthusiasm as the 1970 team."

The 1962 Indians were undefeated, shut out five opponents, and closed the season with a memorable 38-27 win at Princeton. That team scored 236 points, allowed 57, and offered a portrait in total denial against Penn when the Quakers were held to no first downs and a total offense of minus-four yards.

In 1965, Blackman guided Dartmouth to another undefeated season, the Ivy title, and the Lambert Trophy. "That was the nation's only undefeated team that year and the final victory was probably the greatest game in Dartmouth history," said Blackman.

Led by quarterback Mickey Beard and the running of Gene Ryzewicz and Pete Walton, Dartmouth traveled to Princeton for another date with destiny. Princeton had won 17 straight games, trampling everything in sight after Dartmouth had won a 22-21 thriller in the 1963 finale. From every standpoint, the 1965 finale was a classic encounter.

Princeton was favored but Dartmouth won, 28-14, as Beard drove for two touchdowns and passed 79 yards to Bill Calhoun for another while Ryzewicz slashed 12 yards for one more.

That Princeton game was one where some of Blackman's amazing imagination came conspicuously to the surface. He devised a pyramid of linemen and then had defensive back Sam Hawken time a scaling leap to thwart the longrange scoring ability of Princeton's great placekicker, Charlie Gogolak. Psychologically, it left Gogolak and the Tigers in a state of shock. The tactic was exciting, unexpected, and effective. Typical Blackman magic.

That magic now belongs to the University of Illinois where Blackman has chosen to accept the challenge of rebuilding the Illini's football fortunes. He leaves Hanover with a record as a head college coach of 150 victories, 49 losses, and eight ties. Only four other major college head coaches — Bear Bryant of Alabama, Johnny Vaught of Mississippi, Woody Hayes of Ohio State, and Ben Schwartzwalder of Syracuse — have won as many games.

What makes Bob Blackman win? It's not the easy schedule (as they'll tell you in the Southeastern Conference and as they'll find out in the Big Ten) nor is it superior manpower (as the Harvards would lead you to believe).

It's a matter of complete dedication to every detail. For Bob Blackman football is a 365-day proposition, and a compulsive drive for perfection is his credo.

He has proven himself a master of gridiron strategy who can disguise a fullback power play with a multitude of subtle, devastating deceptions. Or, he can create a kickoff return that includes a lateral pass spanning the field.

Blackman's brand of football never will be called dull and always will be called lethal.

Most five-year old kids will tell you they want to be a fireman or a pilot. When Bob Blackman was five years old, he knew he wanted to be a football coach.

As an 18-year old freshman at the University of Southern California, he was bedridden with polio, unable to speak or move his right side. Doctors told his parents that he would never walk again.

At 19, he was back on the Southern Cal football squad, limping through drills and trying futilely to knock over blocking dummies. Finally, Coach Howard Jones took him aside and appointed him assistant freshman coach.

He's been coaching — and winning ever since. He produced winners in five sports while serving in the Navy during World War II. He did take time out to marry a charming lieutenant (junior grade) named Kay Wilson.

"She was pretty and she outranked me," said Ensign Blackman.

After the Navy, Blackman took his family to Monrovia, Calif., and quickly turned a floundering team into a champion within three seasons.

In 1949 he moved to college coaching. In four seasons at Pasadena City College, Blackman's teams had a record of 34-6-3, winning the national junior college championship in 1951 and sharing it in 1952.

From Pasadena, Blackman moved to the University of Denver for two years. His record there was 12-6-2 and produced the Pioneers' first Skyline Conference title in 34 years with a 9-1 record in 1954. That winter he came to Hanover.

After 16 years on the Plain, Blackman's hair is thinner but little else has changed. His ability to win is still strong—and it's this driving urge that played a large part in his decision to accept the challenge of reviving the Illinois program.

Blackman's administrative and imaginative talents have become legend. As one influential Dartmouth stockbroker once said, "If he were president of Ford Motor Company, I'd advise my clients to liquidate their General Motors holdings."

"Bob Blackman is, without doubt, one of the finest coaches in the nation," said President John Kemeny. "We wish him every success in his new position. I only hope that the University of Illinois knows just how lucky it is!"

Blackman Letter

To the many Dartmouth alumni withwhom he worked over the years BobBlackman wrote the following letterabout his decision to take the Illinoiscoaching job:

Much can be said about the uniqueness of Dartmouth. When an individual spends four years at the College it invariably becomes a part of his life from that time on. I have now been at Dartmouth 16 years and I find it hard to imagine that any man could have a greater love for the College than I have.

When I first accepted the coaching position at Dartmouth I received a congratulatory wire that touched me deeply. It was from Earl "Red" Blaik who had coached at Dartmouth from 1934 to 1940 before moving on to West Point. His telegram said, "The seven happiest years of my life were the seven years I spent at Dartmouth." I know well what he meant because the 16 years I have been at Dartmouth have certainly been the most wonderful of my life. It would be impossible to find a more ideal community in which to raise a family, and my wife and I have loved everything about the town, the College, and the fine people we have been associated with. Most important of all, I feel deeply privileged to have had the opportunity to work with many tre- mendously fine young men we have had on our squads during the years I have been at the College. They have been highly intelligent students who have been desirous of making the most of the exceptional educational opportunities at Dartmouth. At the same time they have been sensitive individuals who have been genuinely concerned with the many problems we have today and who are determined to do their part in trying to make this a better world in which to live. Along with their many other interests, however, they have been deeply dedicated to the game of football and have given more of themselves than a coach could possibly ask. My friendship with these young men has been a very meaningful thing to me and is something I will always treasure.

With all the foregoing, the natural question then may be why would a man give up this life to stick his head into what could be a "meat grinder." I am reluctant to use the word "challenge" because I feel it is greatly overused and yet in this case it seems to be the only word that is appropriate.

In the last nine years at Dartmouth we have had the good fortune of winning the Ivy League championship six times and of having three undefeated-untied teams. As a football coach I have to feel there isn't much else I could do at Dartmouth. At Illinois, on the other hand, they have had a 34-62-1 record during the past decade and have lost 26 of 30 games during the past three years. This is compounded by the fact that next year they have an eleven- game schedule that is undoubtedly the toughest in the nation. ... Although this looks frightening, at the

same time I can't help but feel excited at trying to meet this type of challenge. Although I have never been a particular advocate of Bowl games, I must be honest enough to admit that the possibility of someday being able to take a Big Ten championship team out to the Rose Bowl holds a very special attraction. In my last game in high school at Long Beach Poly we played in the Rose Bowl and won the Southern California championship 21-0 over a Glendale High School team led by Frankie Albert (later an All-American quarterback at Stanford and an all-pro quarterback for the San Francisco '49ers). Later on I coached for four years at Pasadena City College where we were fortunate in winning two national junior college championships while playing most of our games in the Rose Bowl. I wouldn't be human if I weren't thrilled at the possibility of taking another team back out to Pasadena where we still have many friends.

Although I am looking forward to going into the Big Ten football competition, at the same time I must point out that I believe strongly in the Ivy League philosophy and feel there is no question but that it has been the best thing for the eight schools involved. Under the framework of the Ivy League rules I also am extremely confident that Dartmouth will continue to turn out representative athletic teams. Leadership starts at the top and the College is fortunate in having another truly great president in John Kemeny. Not only does he have a brilliant mind, but he also has an unusually fine rapport with the students and a genuine interest in athletics. Athletic Director Seaver Peters is also a highly capable individual who is both liked and respected by the members of athletic teams as well as by all the coaches in the athletic department.

One other continuous big plus for the success of the Big Green athletic teams is that intangible but ever-present element known as the "Dartmouth Spirit." Of course, in the final analysis, the success of any athletic team depends to a very large extent on the quality of the players available. The enrollment program that we established in football is now utilized by all the athletic teams at Dartmouth, and with the cooperation of the many dedicated Dartmouth enrollment workers about the country, there should be a continuous flow of good talent. Our freshman team a year ago was the greatest in the history of the College and this year we feel we have already interested more "blue chip" prospects in making application to the College than ever before.

There is nothing worse than a coach who tries to make it appear that his successor is automatically inheriting a "world beater" team and I would like to make it clear that I am not for a moment implying this. Twenty-six very fine senior football players will be graduating from the 1970 Dartmouth team and even though some outstanding varsity talent is returning and some very promising players are coming up from the freshman team, it should be realized that there is considerable "rebuilding" to be done. In fairness it should be pointed out that the other Ivy colleges have some standout players returning including three of the top dozen ball-carriers in the nation last season (Ed Marinaro of Cornell first in yards gained rushing; Hank Bjorklund of Princeton third; and Dick Jauron of Yale twelfth). The point I am trying to make is that in the intensely competitive Ivy League, future victories should not be expected to come easily. The new Dartmouth coach must have the same fine cooperation from many sources that I have so gratefully received during the past 16 years.

One of the most "difficult things to establish is a "winning tradition" and the new coach will have one big advantage in that he will be dealing with a group of young men who have confidence in themselves and think like "winners." In the 15 years since the start of official Ivy League play the "Big Green" team has been the most consistent winner among the eight Ivy League colleges. I feel confident that Dartmouth will go right on winning its share of championships.

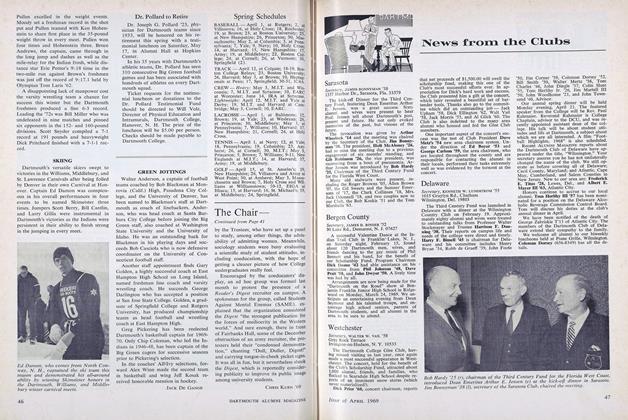

Coach Blackman at work: with his bullhorn at practice and his dictating machine in his Davis Field House office.

Coach Blackman at work: with his bullhorn at practice and his dictating machine in his Davis Field House office.

The Blackman role most familiar to Dartmouth fans was his sideline direction of the Big Green eleven.

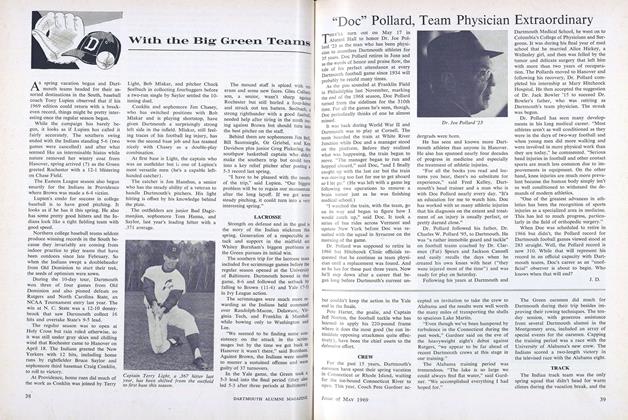

Coach Blackman with Quarterback Bill Gundy '60 and the 1958 IvyLeague trophy, the first championship won in his Hanover regime.

Champions again in 1970, the fourth title wonoutright. Three others were shared.

Bob Blackman with two of his Dartmouth predecessors, Coach DeOrmond "Tuss"McLaughry (1941-42, 1945-54) and Coach Earl "Red" Blaik (1934-40).

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Hear 1970 Called "Great Year for Dartmouth"

February 1971 -

Feature

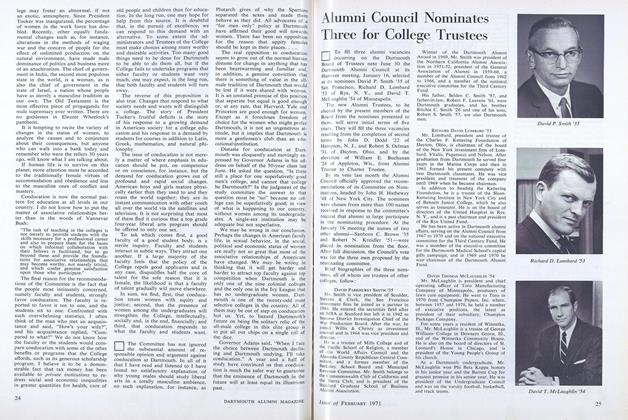

FeatureAlumni Council Nominates Three for College Trustees

February 1971 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

February 1971 -

Article

ArticleA Different View of Vietnam

February 1971 By STEPHEN HART '68 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

February 1971 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1971 By STEPHEN K. ZRIKE '71

JACK DE GANGE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Honorary Degree Citations

July 1957 -

Feature

FeatureMerchant of Menace, Purveyor of Pleasure

JUNE 1977 By DAN NELSON -

Feature

FeatureHONEST TO GOD ACCOMMODATION

OCTOBER 1991 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Cover Story

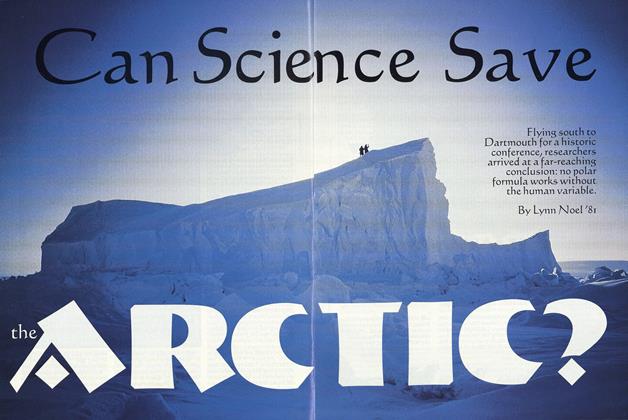

Cover StoryCan Science Save the Arctic?

March 1996 By Lynn Noel '81 -

Feature

FeatureSticking to A Phantom like Glue

March 1998 By Park Taylor '50 -

Feature

FeatureQuestion: What Professional School Gives Credit for Throwing Pies?

NOVEMBER 1988 By Steve Lough '87