During the past academic year many faculty members, while on leave or during the summer recess, traveled to the four corners of the globe in pursuit of knowledge. Now back on campus, they are sharing their experiences in the classroom and in scholarly publications. The following representative sampling illuminates an impressive breadth of intellectual curiosity.

Prof. Norman A. Doenges of the Classics Department concluded, after a year abroad studying a rare document, that letters written in classical antiquity, usually regarded as mere exercises in writing, are really a type of novel in letter form. Professor Doenges spent the 1969-70 academic year at the American Academy in Rome studying a Ninth Century manuscript of the letters of Themistocles, an Athenian statesman and naval commander of the Fifth Century B.C. His research was supported by a College faculty development grant.

Letters from the classical period of Greek antiquity are a special genre. They purport to be the works of famous men, written in the names of Euripides, Socrates, Plato and others. It has long been accepted by classical scholars that these letters were, not written by those whose names were attached to them.

Professor Doenges does not believe that the authorship was capricious or unstudied, such as might be the case if the letters were mere school exercises. "These letters were designed to tell a story, to promote a particular point of view," he says. "They have a beginning, middle and end. They have a plot line. The characterization is very good indeed. They are, in effect, a sort of historical novel."

He hopes to have a manuscript concerning the letters of Themistocles ready for a publisher soon. He has worked out a text of the letters that is as free of error and as near the original as possible, has composed a translation, and has written a commentary.

Despite the novel-like form of the letters, he is convinced that the historical information they contain is accurate. "They contain information about Themistocles which we do not have from any other source and which is confirmed by other evidence. It could not have been invented," Professor Doenges says.

A three-year monitoring of the life signs of potentially active volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest by a team headed by Prof. Robert W. Decker of the Earth Sciences Department has concluded that the volcanic activity there is restless but not immediately threatening.

The volcano most closely studied was Mt. Rainier, a 14,408-foot, snow-covered peak in the Cascade range of Washington State, which last erupted between 100 and 150 years ago. Other members of the monitoring team during the past three summers were John D, Unger, who earned his Ph.D. in geophysics at Dartmouth in 1969, and David H. Harlow '66, who is a second- year graduate student in the department.

Their research effort pooled the resources of four institutions. The personnel was from the College; the funds were from the National Science Foundation; much of the equipment was furnished by the U. S. Geological Survey; and the study was undertaken with the permission and cooperation of the National Park Service.

Instruments chiefly used were seismographs to record the number and intensity of micro-earthquakes in the vicinity of Mt. Rainier. Micro-earth- quakes are movements of the earth too tiny to be felt by human perception, but which do register on sensitive instruments.

Other techniques used at Mt. Rainier were aerial infrared surveys to determine hot spots on the peak, remote sensing thermometers placed in steam vents, signals transmitted to space satellites and back to recording stations on earth, and steam gauges to determine the amount and speed of runoff from some of Mt. Rainier's 26 glaciers. Professor Decker and Mr. Harlow took a portable College seismograph from Mt. Baker in Washington to Mt. Lassen in California, making readings of all the potentially active volcanoes in the high Cascades. The micro-earthquake activity along the way was quite variable.

Excellent new archaeological sites , , and a longer historical time span of occupancy were established as the field-work phase of a study of prehistoric Eskimo and Indian culture on the east shore of Hudson's Bay was completed last summer by a College expedition. The duration of the occupancy of these people, which had previously been set at 500 8.C.-500 A.D. was lengthened to about 1000 A.D. by the discovery of a copper amulet on an earlier field trip.

Prof. Elmer Harp Jr. of the Anthropology Department is principal investigator of the study, begun in 1966 and financed by two grants from the National Science Foundation. Six members of the eight-man expedition are Hanover area residents, five of whom went on the first expedition in 1967. The only newcomer was John Bressett, a Hanover High School senior. His classmate, Douglas Harp, had accompanied his father on earlier trips.

Others in the party were William G. Cavaney '73; William C. McCarthy III '67, a fourth-year Harvard Medical School student who was medical officer; Dr. Jack N. Rinker, formerly of Hanover, research physical scientist with the U. S. Army Topographic Command; Peter Bradley '71 and Pierre McKenzie of the University of Sherbrooke.

The new sites recording the longer period of Eskimo occupation in the area from 500 B.C. onward occurred in Gulf Hazard, the entrance to Richmond Gulf. There the party found nine different ancient Eskimo camp sites, consecutive in time, exposed on a progressively built-up beach line.

The expedition last summer, which lasted two months, did not unearth anything so spectacular as the copper amulet found in 1967, but it obtained larger quantities of data, including charcoal samples.

The amulet, found at Richmond Gulf in an excavated Eskimo summer tent ring, has since been determined by element analysis to be non-North American copper. Further, spectroanalysis showed that the copper had been heated and rolled. Since the Eskimo culture under study, called Dorset by archaeologists, knew nothing of smelting, "the amulet, one had to guess, was of European and likely Viking origin," Professor Harp says.

Daniel J. Geagan, Assistant Professor of Classics, and his wife, Helen von R. Geagan, also a classicist, spent most of the past academic year engaged in classical detective work in Greece where they explored two different but related facets of antiquity. Each was trying to decipher, sometimes as a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle, clues to the social fabric of the past from bits and pieces of art and architecture.

Professor Geagan, a student of epigraphy (Greek inscriptions on stone), worked in museums on records of the Isthmian Games, a festival of poetry, horse racing, and gymnastics held every two years from about the 8th Century B.C. to about the 3rd Century A.D. His research was supported by a fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies.

Mrs. Geagan worked on the reconstruction of a collection of terra cotta plaques, all dedicated to the Greek god Poseicjon, which once hung in a Corinth grove. Time and the accidents of history scattered the shards of these plaques from Greece to Paris and Berlin.

The story of the plaques is a tangled one. A Greek farmer discovered them while excavating a pit in Corinth about 1880. He sold some, violating government laws protecting antiquities, to representatives of the Louvre and the Berlin Museum. Those fragments in Germany have subsequently been divided between East and West Berlin. A later, legal excavation by an American archaeological expedition in 1906 unearthed still more fragments. Additional fragments were collected by archaeologists later. From this scattered record, Mrs. Geagan says, much can be learned about the art, myths, and history of classical Greece. Technical data about the rigging of ancient ships and the development of pottery are also gained.

By using photographs of pieces in the Paris and Berlin Collections, Mrs. Geagan was able to match them up with fragments still in Greece. An article on her research will appear in Anzeiger, published by the German Archaeological Institute of Berlin.

In collaboration with Prof. Michael Jameson of the University of Pennsylvania, Professor Geagan is planning a book on the inscriptions, testimonia, and history of the Isthmian Games and Festivals. It will be published by the American School of Classical Studies in Athens.

The study of the reaction of a stalk-like part of a single-celled organism to light may yield important clues to the multicelled workings of the human eye, reports Prof. David S. Dennison of the Biological Sciences Department. He devoted the past academic year to research on the single-celled organism, Phycomyces, at the California Institute of Technology. There he worked with Dr. Max Delbruck, a Nobel laureate with whom he studied as a graduate student 15 years ago. His research was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Phycomyces is a genus of fungus akin to breadmold. Professor Dennison has been studying the responses of Phycomyces to light and other stimuli since graduate school days. He has also become an expert at macrophotography, used to record the minute movements of the Phycomyces stalks reacting to light and other stimuli.

Being a single-celled organism, Phycomyces is much simpler to study than the human eye which is composed of millions of light-sensitive cells. If the chemical mechanism that triggers the light response in Phycomyces can be isolated, it could well have important bearing on the study of the mechanism of the human eye.

The two main parts of Phycomyces are the mycelium, a root-like maze of threads from which arise the sporangiophores, which look somewhat like Tinkertoy rods topped with a ball. The sporangiophore part reacts measurably to light, being attracted to white light and repelled by ultra-violet light.

In addition the sporangiophore reacts to gravity. If it is moved from the perpendicular to the horizontal, it begins to bend upright in a few hours. Phycomyces also reacts to mechanical stretching; if a glass fiber pushes it off the vertical line, the sporangiophore pushes back quickly toward the center. It even has a radar-type avoidance response. If it is placed near an object in the dark, it grows away from the object. The gravity and light response of Phycomyces originate in different processes in the cell, but somewhere along the line they both reach a branch point. From that point both responses effect differential growth of the sporangiophore. If the origin points of the responses and the branch point at which they meet can be determined, important new scientific knowledge will have been gained.

Professor Dennison intends to keep at his research in the time available outside his teaching duties. "It's really working on the frontiers of knowledge," he says, "I feel that teaching must go with research, and research with teaching. I couldn't do one without the other."

The computer is an everyday tool in President Kemeny's office and his secretary,Mrs. Ruth LaBombard, has become adept, under the very best of tutelage, atusing it to obtain information for the President.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Hear 1970 Called "Great Year for Dartmouth"

February 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThe Blackman Era: Sixteen Special Years

February 1971 By JACK DE GANGE -

Feature

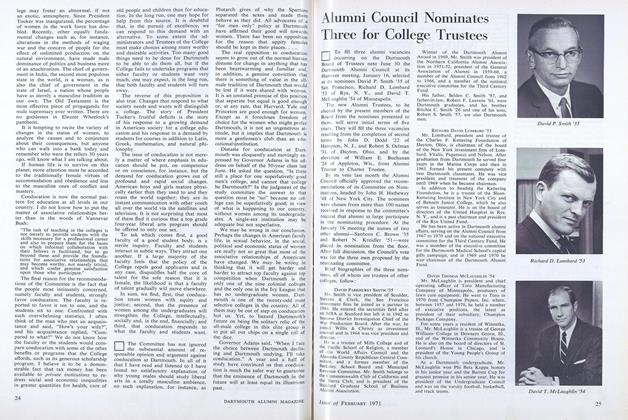

FeatureAlumni Council Nominates Three for College Trustees

February 1971 -

Feature

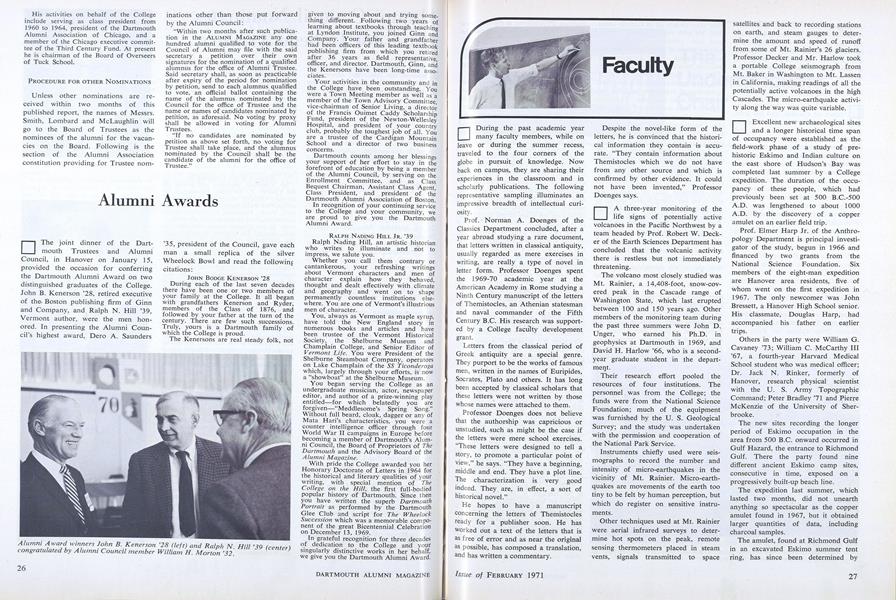

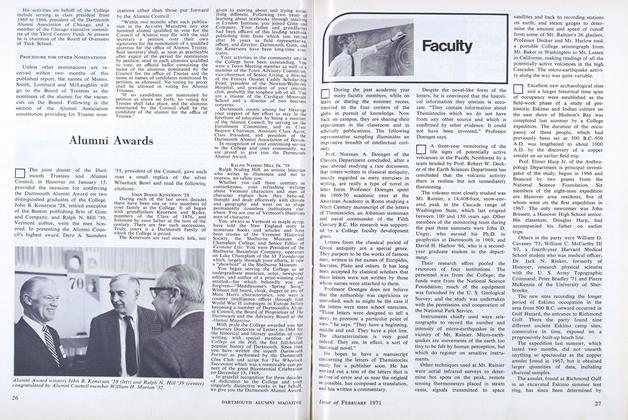

FeatureAlumni Awards

February 1971 -

Article

ArticleA Different View of Vietnam

February 1971 By STEPHEN HART '68 -

Article

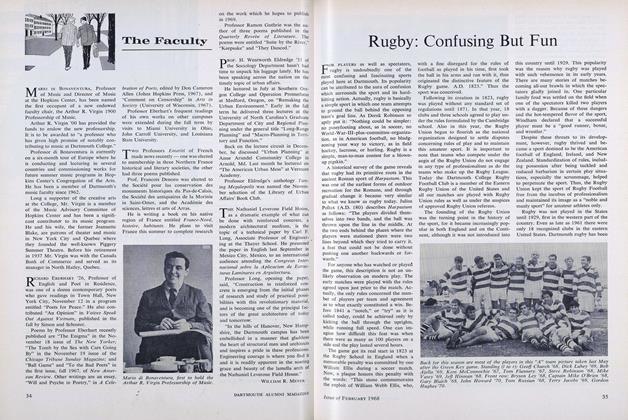

ArticleThe Undergraduate Chair

February 1971 By STEPHEN K. ZRIKE '71

WILLIAM R. MEYER

-

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

FEBRUARY 1968 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

FEBRUARY 1969 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

JANUARY 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleThe Faculty

JUNE 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleFaculty

DECEMBER 1970 By WILLIAM R. MEYER -

Article

ArticleFaculty

MAY 1971 By WILLIAM R. MEYER

Article

-

Article

ArticleFavorite of Dartmouth Students Dead

February, 1911 -

Article

ArticleTHIRTY-SIX FRESHMEN WIN HIGH SCHOLARSHIP STANDING

MARCH, 1927 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

APRIL 1989 -

Article

ArticleAstronaut James Newman '78:

May 1994 -

Article

ArticleCocktails, Anyone?

September | October 2013 -

Article

ArticleTENNIS

JUNE 1971 By JACK DEGANGE