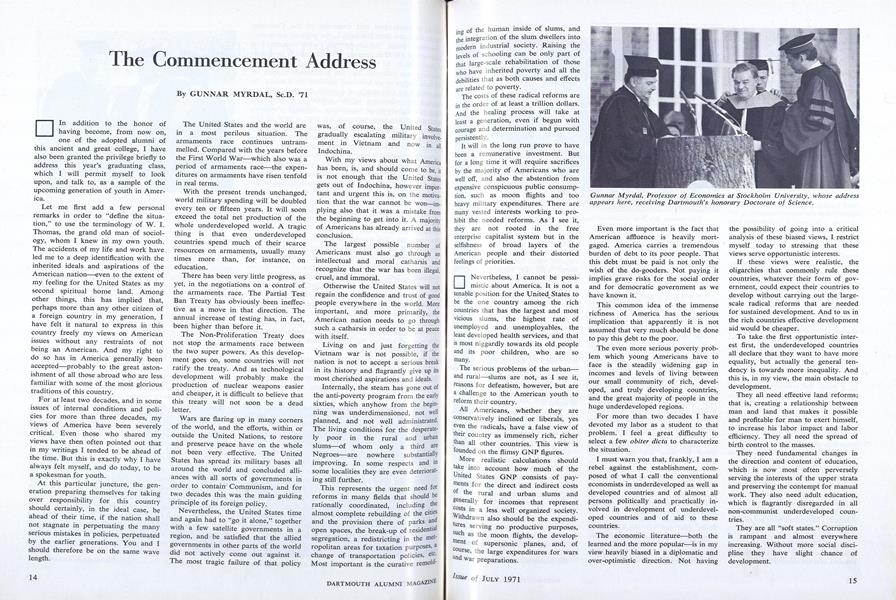

In addition to the honor of having become, from now on, one of the adopted alumni of this ancient and great college, I have also been granted the privilege briefly to address this year's graduating class, which I will permit myself to look upon, and talk to, as a sample of the upcoming generation of youth in America.

Let me first add a few personal remarks in order to "define the situation," to use the terminology of W.I. Thomas, the grand old man of sociology, whom I knew in my own youth. The accidents of my life and work have led me to a deep identification with the inherited ideals and aspirations of the American nation—even to the extent of my feeling for the United States as my second spiritual home land. Among other things, this has implied that, perhaps more than any other citizen of a foreign country in my generation, I have felt it natural to express in this country freely my views on American issues without any restraints of not being an American. And my right to do so has in America generally been accepted—probably to the great astonishment of all those abroad who are less familiar with some of the most glorious traditions of this country.

For at least two decades, and in some issues of internal conditions and policies for more than three decades, my views of America have been severely critical. Even those who shared my views have then often pointed out that in my writings I tended to be ahead of the time. But this is exactly why I have always felt myself, and do today, to be a spokesman for youth.

At this particular juncture, the generation preparing themselves for taking over responsibility for this country should certainly, in the ideal case, be ahead of their time, if the nation shall not stagnate in perpetuating the many serious mistakes in policies, perpetuated by the earlier generations. You and I should therefore be on the same wave length.

The United States and the world are in a most perilous situation. The armaments race continues untrammelled. Compared with the years before the First World War—which also was a period of armaments race—the expenditures on armaments have risen tenfold in real terms.

With the present trends unchanged, world military spending will be doubled every ten or fifteen years. It will soon exceed the total net production of the whole underdeveloped world. A tragic thing is that even underdeveloped countries spend much of their scarce resources on armaments, usually many times more than, for instance, on education.

There has been very little progress, as yet, in the negotiations on a control of the armaments race. The Partial Test Ban Treaty has obviously been ineffective as a move in that direction. The annual increase of testing has, in fact, been higher than before it.

The Non-Proliferation Treaty does not stop the armaments race between the two super powers. As this development goes on, some countries will not ratify the treaty. And as technological development will probably make the production of nuclear weapons easier and cheaper, it is difficult to believe that this treaty will not soon be a dead letter.

Wars are flaring up in many corners of the world, and the efforts, within or outside the United Nations, to restore and preserve peace have on the whole not been very effective. The United States has spread its military bases all around the world and concluded alliances with all sorts of governments in order to contain Communism, and for two decades this was the main guiding principle of its foreign policy.

Nevertheless, the United States time and again had to "go it alone," together with a few satellite governments in a region, and be satisfied that the allied governments in other parts of the world did not actively come out against it. The most tragic failure of that policy was, of course, the United State gradually escalating military involvement in Vietnam and now in all Indochina.

With my views about what America has been, is, and should come to be. it is not enough that the United States gets out of Indochina, however important and urgent this is, on the motivation that the war cannot be won implying also that it was a mistake from the beginning to get into it. A majority of Americans has already arrived at this conclusion.

The largest possible number of Americans must also go through an intellectual and moral catharsis and recognize that the war has been illegal, cruel, and immoral.

Otherwise the United States will not regain the confidence and trust of good people everywhere in the world. More important, and more primarily, the American nation needs to go through such a catharsis in order to be at peace with itself.

Living on and just forgetting the Vietnam war is not possible, if the nation is not to accept a serious break in its history and flagrantly give up its most cherished aspirations and ideals.

Internally, the steam has gone out of the anti-poverty program from the earl) sixties, which anyhow from the beginning was underdimensioned, not well planned, and not well administrated. The living conditions for the desperately poor in the rural and urban slums—of whom only a third are Negroes—are nowhere substantially improving. In some respects and in some localities they are even deteriorating still further.

This represents the urgent need for reforms in many fields that should be rationally coordinated, including the almost complete rebuilding of the cities and the provision there of parks and open spaces, the break-up of residential segregation, a redistricting in the metropolitan areas for taxation purposes, a change of transportation policies, etc. Most important is the curative remolding of the human inside of slums, and the integration of the slum dwellers into modern industrial society. Raising the levels of schooling can be only part of that large-scale rehabilitation of those who have inherited poverty and all the debilities that as both causes and effects are related to poverty.

The costs of these radical reforms are in the order of at least a trillion dollars. And the healing process will take at least a generation, even if begun with courage and determination and pursued persistently.

It will in the long run prove to have been a remunerative investment. But for a long time it will require sacrifices by the majority of Americans who are well off, and also the abstention from expensive conspicuous public consumption, such as moon flights and too heavy military expenditures. There are many vested interests working to prohibit the needed reforms. As I see it, they are not rooted in the free enterprise capitalist system but in the selfishness of broad layers of the American people and their distorted feelings of priorities.

Nevertheless, I cannot be pessimistic about America. It is not a tenable position for the United States to be the one country among the rich countries that has the largest and most vicious slums, the highest rate of unemployed and unemployables, the least developed health services, and that is most niggardly towards its old people and its poor children, who are so many.

The serious problems of the urban— and rural—slums are not, as I see it, reasons for defeatism, however, but are a challenge to the American youth to reform their country.

All Americans, whether they are conservatively inclined or liberals, yes even the radicals, have a false view of their country as immensely rich, richer than all other countries. This view is founded on the flimsy GNP figures.

More realistic calculations should take into account how much of the United States GNP consists of payments for the direct and indirect costs of the rural and urban slums and generally for incomes that represent c°sts in a less well organized society. Withdrawn also should be the expenditures serving no productive purposes, such as the moon flights, the development of supersonic planes, and, of course, the large expenditures for wars and war preparations.

Even more important is the fact that American affluence is heavily mortgaged. America carries a tremendous burden of debt to its poor people. That this debt must be paid is not only the wish of the do-gooders. Not paying it implies grave risks for the social order and for democratic government as we have known it.

This common idea of the immense richness of America has the serious implication that apparently it is not assumed that very much should be done to pay this debt to the poor.

The even more serious poverty problem which young Americans have to face is the steadily widening gap in incomes and levels of living between our small community of rich, developed, and truly developing countries, and the great majority of people in the huge underdeveloped regions.

For more than two decades I have devoted my labor as a student to that problem. I feel a great difficulty to select a few obiter dicta to characterize the situation.

I must warn you that, frankly, I am a rebel against the establishment, composed of what I call the conventional economists in underdeveloped as well as developed countries and of almost all persons politically and practically involved in development of underdeveloped countries and of aid to these countries.

The economic literature—both the learned and the more popular—is in my view heavily biased in a diplomatic and over-optimistic direction. Not having the possibility of going into a critical analysis of these biased views, I restrict myself today to stressing that these views serve opportunistic interests.

If these views were realistic, the oligarchies that commonly rule these countries, whatever their form of government, could expect their countries to develop without carrying out the large- scale radical reforms that are needed for sustained development. And to us in the rich countries effective development aid would be cheaper.

To take the first opportunistic interest first, the underdeveloped countries all declare that they want to have more equality, but actually the general tendency is towards more inequality. And this is, in my view, the main obstacle to development.

They all need effective land reforms; that is, creating a relationship between man and land that makes it possible and profitable for man to exert himself, to increase his labor impact and labor efficiency. They all need the spread of birth control to the masses.

They need fundamental changes in the direction and content of education, which is now most often perversely serving the interests of the upper strata and preserving the contempt for manual work. They also need adult education, which is flagrantly disregarded in all non-communist underdeveloped countries.

They are all "soft states." Corruption is rampant and almost everywhere increasing. Without more social discipline they have slight chance of development.

These things are opportunistically kept out of the literature on underdevelopment and planning for development. On the whole, these reforms must be carried out by the underdeveloped countries themselves. There is little we in the developed countries can do to assist them in these matters.

But their situation is so desperate that most certainly they need aid. Globally speaking, aid from the developed countries has been diminishing, at the same time that its quality has been deteriorating. And the United States leads in this development.

As I have pointed out, we are now even juggling the statistics to hide from ourselves the low quality, in real terms, of our aid and assistance, and its low quantity as loans have been allowed to increase at the expense of grants; and both loans and grants have been tied to export from the "donor" country.

What I foresee, if policies in both underdeveloped and developed countries are not radically changed, is a continuous trend towards greater inequality in the underdeveloped countries, a rapid increase of the under- utilization of labor and, following this, a growing misery among the masses in the huge rural and urban slums.

Meanwhile there might be "economic growth" as measured by national product or income—for which the statistics are even more biased and grossly faulty than in developed countries—and also higher incomes and levels of living for the tiny upper class, including what in these countries is called the "middle class."

I have been painting with a wide brush. But I believe I have been telling what is essentially the somber truth.

It is an understatement, bordering on the blatantly ridiculous, to say that the situation in the United States and in the world, which the youth is inheriting from their elders and that it will have to master, is one of mounting difficulties and grave dangers. When now, at the end of this brief address, I venture to give my advice on how young Americans should react to it, I speak with humility but also with great seriousness.

First, I would warn against defeatism. I cannot be pessimistic about America. I have never belonged to those who now and then over the decades, as I can well remember, have said that "it can happen here," not even during the time McCarthyism was a dampening pressure over the nation's life.

Speaking to youth, I must insist that it is your country. You will soon gradually inherit all the power to do with the country what you please. History is not a predetermined fate. The future will be as you will make it.

It is not a revolution America needs but large-scale, indeed radical, reforms. They should be rationally conceived and should with utmost care preserve and protect the methods for peaceful change that we have gradually developed over centuries of democratic growth.

One of the dangerous effects of a laissez faire policy, that permits problems to remain unsolved and to become intensified, is that groups of people and sometimes whole nations come to lose their confidence in peaceful change through democratic and non-violent means and so become desperate and apt to resort to force and violence. That is what I call defeatism.

Already the Bible warned against trying to drive out the Devil by Beelzebub. It also warned that the one who takes up the sword shall perish by the sword. Riots lead to repression, violence to counter-violence. If there is anarchy, and if it is allowed to spread and grow, at the end there is nothing left but the police state.

In its foreign relations the United States must feel the responsibility of being one of the super-states but at the same time realize its dependence on the rest of the world. It cannot afford moral and political isolation.

There are people in America, and at times they might have been in the majority, who feel that it does not matter what the world thinks of its policies. They believe that America's financial and military power makes it possible for the United States to ignore world opinion. This is proving to be a tragic mistake.

Once in my youth, more than a quarter of a century ago, I wrote a book about America's internal problems of justice, liberty, and equality. I was led to consider, in the last chapter of that book, An American Dilemma, the role in the world I foresaw for America when it became "America's turn in the endless sequence of main actors on the world stage." I wrote then, and I wan! to repeat it:

America has now joined the world and is tremendously dependent upon support and goodwill of other countries. Its rise to leadership brings this to a climax. None is watched so suspiciously as the one who is rising. None has so little license, none needs all his virtue so much as the leader.

I refuted the idea I already then found common in America that financial and military power could substitute for the moral power of earning the goodwill of decent people all over the world. Without followers, the leader is no longer a leader, but only an isolated aberrant. And if he then is strong like America, he becomes a dangerous aber- rant, dangerous for himself and for the world.

The leadership the world now needs from the United States must spring from clear thoughts, rational analysis, and devotion to peaceful living and to development. It should be possible to move more courageosuly towards setting a stop to the armaments race and towards giving the poor colored nations of the world trade outlets and substantial financial aid, directed upon social as well as economic advance and not only strengthening the reactionary oligarchies.

In the United States itself this would assume public education and not only the half-truths of official propaganda, and also a resistance to nationalistic pressure groups and vested interests. The universities should have an important role in calling forth the much- needed intellectual and moral catharsis even in this field of international relations as in the national one of consolidating the American people.

It is to America's youth we must attach our hope. America and the world are not in a healthy state. It is your duty, individually and collectively, to strive against a further deterioration and for initiating reforms, which, as I said, must be courageous and far- reaching. And you can take your stand upon those ideals of justice, liberty, equality, and brotherhood, _ which I once called the "American creed," at the same time as I pointed out that they are our common ideological heritage in the whole world which slowly developed over centuries and came to flourish in the glorious era of Enlightment.

These ideals need to be purified and fortified. In particular, the general community interests must be stressed against the anarchistic tendency to rugged individualism, which in America is such an unfortunate heritage from frontier society.

Liberty should thus not imply the freedom for every crank and criminal to buy and possess a murderous weapon. America is paying a heavy price in asocial violence for its eccentric liberty doctrine in this respect.

Neither should liberty be allowed to mean that a majority of the people is eft free to become ever more affluent, while a minority, and a large minority, is pressed down into an alienated underclass. Collusion between people to exclude certain ethnic or religious groups from living in their neighborhood, working in the professions or in trade, sending children to their schools, or from eating in their restaurants and buying in their shops, is not a legitimate exercise of liberty but an insolent infringement on other people's rights to liberty.

There must be equality of opportunity, or else this nation will disintegrate into factions between which there is no national solidarity.

Minimum standards in health and educational facilities and more generally in living levels and in employment opportunities must be established, enforced, and paid for. In these respects the United States is still a comparatively backward country. And this is the main reason for the lack of true liberty for all in America.

Again, in the international arena the United States should not interpret its national liberty as the right to police the world on its own terms and as a simple exertion of its might. Attempts to follow that inconsiderate line—as in Vietnam—lead to gross policy failures and will leave the United States standing isolated in an indifferent and gradually even hostile world.

And the United States must end motivating what it is prepared to do for aiding the poor countries by trying to convince itself that it is being done for a national political purpose—"in the best interest of the United States" or even "for the security of the United States." That type of motivation for foreign aid is neither effective in calling forth a national sacrifice at home or in other rich countries, nor is it soliciting goodwill in the poor countries.

The international leadership needed from the United States must be in the form of vigorous attempts to strengthen international compassion and solidarity, necessary to build up intergovernmental cooperation within the United Nations for disarmament, global peace-keeping, and joint responsibility for the development and welfare of the poor countries.

Of such true internationalism we have in the last two decades seen too little. National selfishness is as dangerous for building up a peaceful progressive international community, as rugged individualism is for consolidating the nation state at home.

I have a strong belief that our national and international problems can be solved by pressing on for an ever more faithful realization of our inherited ideals of justice, liberty, equality, and brotherhood. And our hope must be that the coming generation will more devotedly and effectively than their elders' see the light and do their moral duty.

Gunnar Myrdal, Professor of Economics at Stockholm University, whose addressappears here, receiving Dartmouth's honorary Doctorate of Science.

The seniors this year elected to make Class Day a very informal affair.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

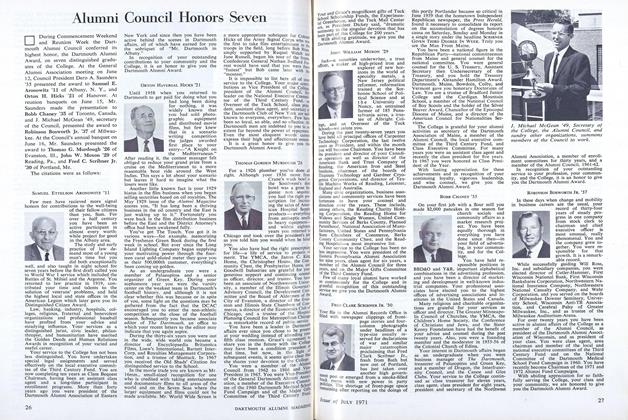

FeatureAlumni Council Honors Seven

July 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1971 By JOHN L. SULLIVAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1971 By honoris causa. -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1971

July 1971 By CHARLES J. KERSHNER -

Feature

FeatureMcCulloch Heads Council

July 1971 -

Feature

FeatureClass Association Delegates Meet to Discuss Coeducation

July 1971

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThorne Smith 1914

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

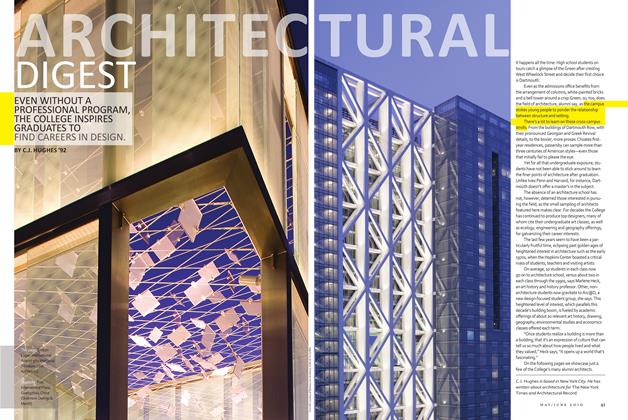

FeatureArchitectural Digest

May/June 2010 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Feature

FeatureCarnival Post-Mortem

March 1956 By CLIFFORD L. JORDAN '45 -

Feature

FeatureHow Do You Socialize a Freshman?

September 1993 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

Feature'Raucous behavior of a different sort'

December 1978 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureELECTION-YEAR CONFERENCE

April 1956 By ROBERT H. GILE '56