Volume I: 1940-1956. Edited,with commentary and annotation, byAllan W. Cameron '60. Cornell UniversityPress, 1971. 451 pp. $15.

Although in this collection of documents Mr. Cameron of Tufts' Fletcher School contributes to our understanding of the Vietnamese conflict, unwittingly he also sustains the illusion that what governments proclaim corresponds with their intent.

Vietnam Crisis consists of 190 items, "remarks," "declarations," "memoranda," "speeches," "proclamations," "communiques," "recognitions," "manifestos," "debates," "proposals," and "treaties," all in the public domain and issued by the principals, East and West, involved in Indochina between 1943 and 1956. Mr. Cameron selected his materials from more than 3000 possibilities and reminds us that "many crucial items remain classified by the governments concerned." In the light of TheNew York Times stupefying revelations of June 13, 14, and 15, this reminder is not only too true but forces us to rethink the value of public documentation.

Supplying short commentaries which precede each chronological section, Mr. Cameron surveys the periods of FDR's determination to prevent French reoccupation of her Indochinese colonies, through America's support for flagging France, to 1956 when France, following the Geneva Conference, was "replaced" by the United States.

In surveying these years, Mr. Cameron cresses the development of American policy; he discerns, in Vietnam, two paramount issues: "the conflict between Communism and anti-Communism" and "the unification of the country."

These issues are, indeed, central to our understanding; but how, then, are we to take Mr. Cameron's very first sentence: After 1961 the United States became involved in what was to be the longest, second-largest, and most unpopular foreign in American history—the conflict in Vietnam?" His own volume proceeds to tell an utterly different tale. From at least 1942, Washington would insist that whatever happened in Southeast Asia, two linked considerations remained uppermost: America would play the decisive role, and the Indochmese, "people of small stature" in Roosevelt's words, were not to decide their own futures.

From FDR's death, successive administrations concluded that for the sake of European security France must be supported in Asia. In 1950 Charles Bohlen, in a secret Washington briefing (not included by Cameron), stated, "... if we can help France to get out of the existing stalemate in Indochina, France can do something in Western Europe." The other American preoccupation, after 1949, was China, and here a key document is again not in VietnamCrisis. In July 1949, Secretary of State Acheson instructed a special committee headed by Philip Jessup: "You will please take as your assumption that it is a fundamental decision of American policy that the United States does not intend to permit further extension of Communist domination on the continent of Asia or in the Southeast Asia area."

America's insistence on global hegemony, and its recognition of the obstacles involved, do not emerge clearly from Cameron's volume although the evidence is abundant. In 1951 David Bruce, now our envoy at the Paris peace talks, pointed out that in Indochina alone "a war [was] now being conducted to try to suppress the overtaking of the whole area by Communists," a statement echoed in a 1964 memorandum of General Maxwell Taylor, asserting that Vietnam constituted "the first real test of our determination to defeat Communist wars of national liberation ..." (The New YorkTimes, June 13, 1971).

Although the Vietnamese—not to mention the French—wished to shape their own destiny, we can read in Cameron the Nixon, Dulles, and Eisenhower references to Southeast Asia "going under," the loss to "the free world" of "the rich empire of Indonesia" (if Indochina "went") and "the falling domino principle." These fears of weakness, of loss, of impotence, appear again in TheNew York Times revelations, most starkly perhaps in Walt Rostow's "at this stage of history we are the greatest power in the world—if we behave like it" (The NewYork Times, June 15, 1971).

Cameron's useful book is marred by lack of an index and an inadequate bibliography of "Secondary Works." Not to include, for instance, George Kahin and John Lewis, Anthony Eden or Dean Acheson, Gabriel Kolko or Vo Nguyen Giap (or a host of other Vietnamese analysts) leaves today's student of Vietnam unprepared for the cynical catalogue of "U. S. aims" compiled in March 1965 by Assistant Secretary of Defense John McNaughton:

"70%-To avoid a humiliating U.S. defeat ... 20%—To keep South Vietnam from Chinese hands.

10%—To permit the people of South Vietnam to enjoy a better, freer, way of life.

ALSO—To emerge from the crisis without unacceptable taint from methods used.

NOT—To "help a friend," although it would be hard to stay if asked out." (Capitals in the original, The New York Times, June 15, 1971.)

As Eisenhower looked back, he saw it all: "It was almost impossible to make the average Vietnamese peasant realize that the French ... were really fighting in the cause of freedom, while the Vietminh, people of their own ethnic origins, were fighting on the side of slavery."

Mr. Mirsky, Dartmouth Associate Professorof History and Chinese, is Co-Director ofthe East Asia Center.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

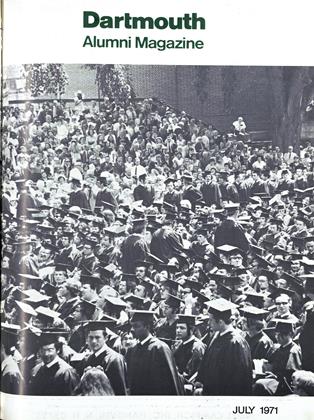

FeatureThe Commencement Address

July 1971 By GUNNAR MYRDAL, Sc.D. '71 -

Feature

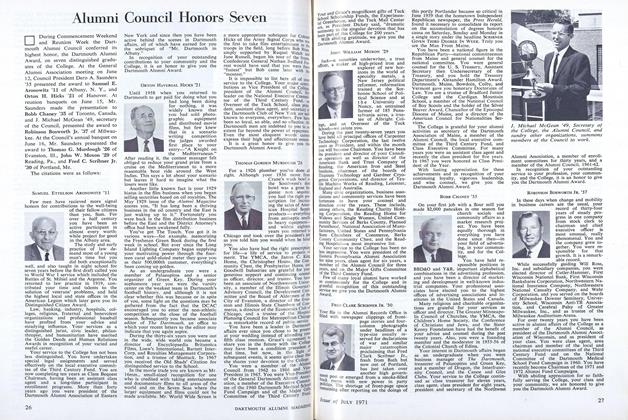

FeatureAlumni Council Honors Seven

July 1971 -

Feature

FeatureThe Fifty-Year Address

July 1971 By JOHN L. SULLIVAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1971 By honoris causa. -

Feature

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1971

July 1971 By CHARLES J. KERSHNER -

Feature

FeatureMcCulloch Heads Council

July 1971

JONATHAN MIRSKY

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JULY 1968 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

MAY 1973 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

SEPTEMBER 1985 -

Article

ArticleA FACULTY COMMENTARY

JUNE 1970 By JONATHAN MIRSKY -

Feature

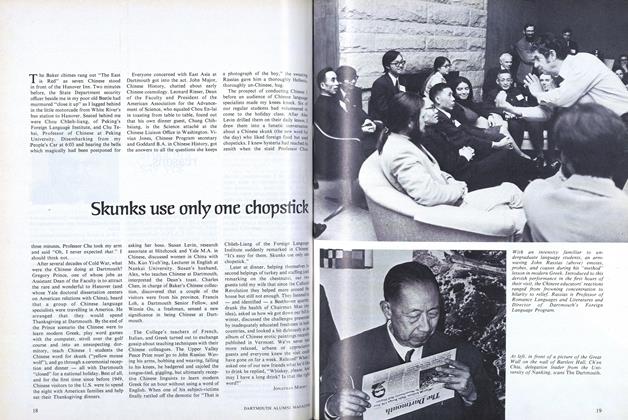

FeatureSkunks use only one chopstick

January 1974 By JONATHAN MIRSKY -

Article

ArticleVox

June 1975 By JONATHAN MIRSKY