TODAY the CIA sent me my file. Among other items, this agency for which I help pay the bills refers to me, "subject," as "fairly knowledgeable on Communist China and North Vietnam as well as other areas of Southeast Asia."

It's a bit tooth-gritting being referred to by my CIA employees as merely "fairly knowledgeable." Since gathering such intelligence on me inside the country (the evaluation is quoted from a secret memorandum of the ClA's Domestic Contact Service) is illegal, shouldn't the agency have the grace to classify me "very knowledgeable" or at least "knowledgeable"? Perhaps "fairly knowledgeable" is suspicious enough not only for my CIA employees, but for my employers.

My employers are Dartmouth's Trustees, President and their administrators. About a month ago a Trustee remarked to a colleague of mine (I'm paraphrasing slightly out of no doubt needless caution): "Ah, Dr. X (Trustees are very punctilious) I hope we may count on someone to provide an alternative view of Asia to that of, shall we say, our friend Professor Mirsky."

This Trustee and I, naturally enough, have never met, unless like some Asian potentate he masquerades about Bartlett Hall Bazaar disguised as one of his subjects. For whatever reason, my invisible employer dislikes my knowledge.

In CIA Director Cable 62520 the "subject" (me) is "CONSIDERED ANTI-U.S. VIS-A-VIS VIETNAM." For a moment I imagined it said I was "anti-us." That would have explained everything.

Being anti-us is the ultimate crime against any institution. Not everyone who is anti-us gets to drink hemlock. Some get "terminated," which is the CIA's word for assassination of their own foreign employees (actually "termination with extreme prejudice") and Dartmouth's word for firing.

How one is anti-us can be broadly construed and depends a lot on time, place, and who's irritated.

"Siding with the students," having "student groupies," or, as one colleague of mine described me (trying to account for my large classes) having "sex-appeal as a revolutionary," is anti-us. Being persistently, publicly, vocally anti-war, anti-ROTC, anti-grade, or pro-coed before these became majority views, is anti-us.

My tenure committee, made up of senior colleagues from four departments, disdained the opportunity for excommunication and recommended to the dean of the faculty that I be retained either with tenure, or, in the event "that he continues absolutely to refuse tenure that his present appointment be renewed for not less than five years." My colleagues even made friendly noises about my views: "As a gadfly to us all Jonathan plays a very important role, one the College can ill-afford to lose." One man's gadfly is another's asp.

I expect screams of protest. How about A, B, and C? Didn't they get promoted? There is indeed a tiny number of anti-us exceptions. But along with the well-qualified scholar-teachers and safe mediocrities who rise to the top, it's good to remember the rest of the letters in the alphabet. John Kemeny speaks the truth in his Five-Year Report when he points out that untenured faculty "constantly being examined on their performance . . . are [not] likely to try out radically new ideas in education." If you're in Economics, you better use "the textbook" and not paperbacks from Lenin to Friedman. If you teach and write in numbers of "disciplines," you probably won't "fit" into any department although you were hailed as a triple threat when you arrived If you're in Spanish or Biology and you annoy the wrong folks, start packing. If you're in Biochemistry and you cross the chairman, forget going to department meetings. And if you're Dona Strauss in Mathematics or Paul Knapp in Chemistry and you occupy Parkhurst - even if you came out before the sheriff ordered you to, and your department, if you're Dona, unanimously voted to keep you - call the movers.

As Dona said in her 1969 trial before the Committee Advisory to the President: "I believe that this hearing shows that something is terribly wrong here. It seems to be a symptom of what is wrong in our society that reasonable and humane men such as you, can find yourselves acting in this situation, not tostop the killing, but to crush the people who are protestingagainst it." (Italics added.)

Pain, disappointment, and anger rise to the surface as I face the loss of pleasures connected with working at Dartmouth. Being a professor aroused initial responses now recalled with shame: swiveling about in my new office, pushing telephone buttons (at one point I had two offices), and summoning the secretary.

What I will like to remember are my students, whom I leave with sorrow. They go in every direction: one is an intelligence adviser to our Pacific commander and another went to federal prison for refusing induction.

With my students I learned to 'teach careful reading, writing, listening, and talking. I hoped they would be original, adventurous, irreverent, and radical if they wanted to be. It always seemed to me that we should follow our interests as thoroughly as possible; this can mean both familiar academic pursuits and what others might call far-out pathways. Together we studied Asia for its own sake, not merely as an appendage of the West, and Chinese language to get inside one of its great cultures. Encouraging them to deny national authority per se would, I hoped, move them to understand certain systemic American defects to be more than regrettable errors. In courses concentrating on literature we set novels, stories, and plays in the social and class context which underpin the more traditionally studied symbols, metaphors, and styles. For nine years students have been dear friends, critics, allies, and supporters.

Faculty and staff friends have shared such experiences and others. Teaching and struggling, arguing over College and national politics, sometimes going to court and prison together, my male and later my female colleagues form a loose but comradely collective. A number of secretary friends, especially the first and last, make me more aware of how many people would be doing something different if they were another sex.

When John Kemeny asserts that only tenured radical thinkers can be sure to survive pressure from the administration, he's right. Opposing "the College" mainstream on teaching, research, student life, and faculty-administrative relationships is like being ANTI-US in the eyes of the CIA. Surveillance can lead to termination. Like Dartmouth's President, "I believe that this freedom is essential for the intellectual life of the institution." Yes, but one shouldn't have to wear a bullet-proof muzzle.

A young man asked by the Times for his views on Paul Revere during a celebration near the scene of The Ride replied, "Hell, got nothing to do with history, nothing. All we can do is go pick up our unemployment checks." I know how he feels; when you're not working Great Issues shrink a bit. But the poet Marge Piercy still says something to me: "All predators prefer a dinner that does not fight."

Mr. Mirsky taught Asian studies at Dartmouth for nine years.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Battle of Bunker Hill

June 1975 By LEWIS STILWELL -

Feature

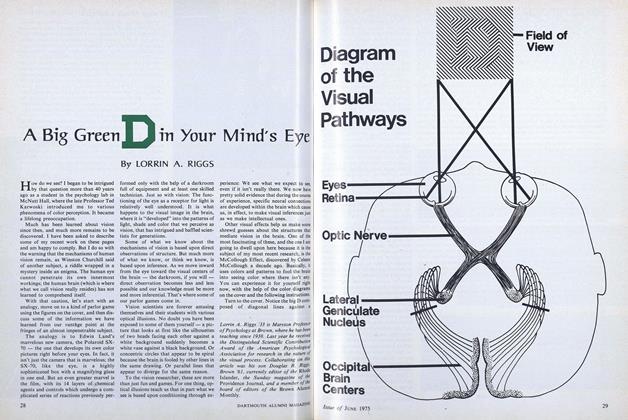

FeatureA Big Green D in Your Mind's Eye

June 1975 By LORRIN A. RIGGS -

Feature

FeatureCommencement

June 1975 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureThe Orioles Are Back

June 1975 By DANA S. LAMB -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

June 1975 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleHonorary Degrees

June 1975

JONATHAN MIRSKY

-

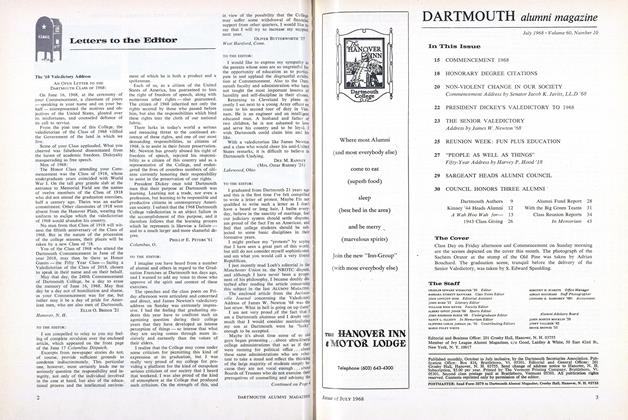

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

JULY 1968 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

MAY 1973 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters

SEPTEMBER 1985 -

Article

ArticleA FACULTY COMMENTARY

JUNE 1970 By JONATHAN MIRSKY -

Books

BooksVIETNAM CRISIS: A DOCUMENTARY HISTORY.

JULY 1971 By JONATHAN MIRSKY -

Feature

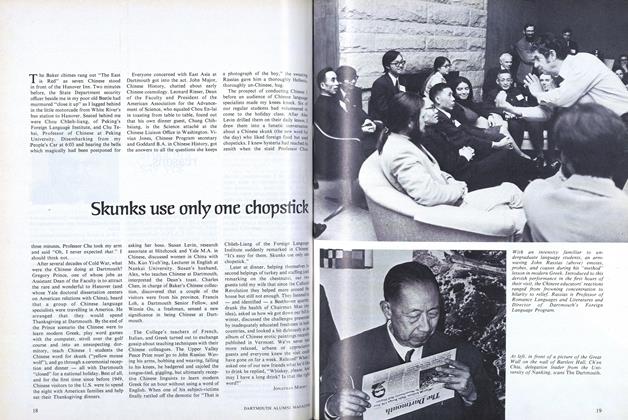

FeatureSkunks use only one chopstick

January 1974 By JONATHAN MIRSKY

Article

-

Article

ArticleAlumni Council Meeting

October 1944 -

Article

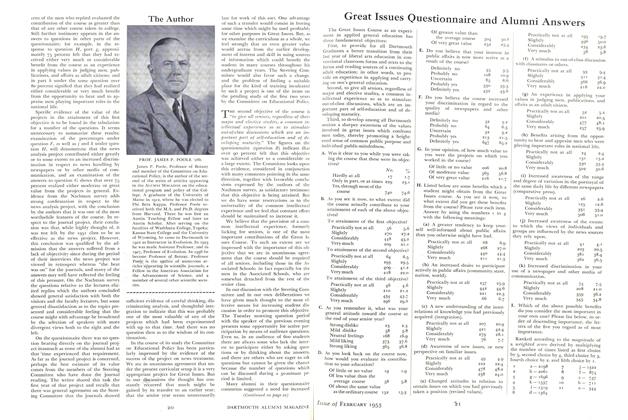

ArticleGreat Issues Questionnaire and Alumni Answers

February 1953 -

Article

ArticleSummer Scholars

October 1951 -

Article

ArticleThe College

OCTOBER 1972 -

Article

ArticleHurricane Provides Memorable College Opening

October 1938 By 60-Mile Gale -

Article

ArticleSkiing

January 1960 By CLIFF JORDAN '45