In late November, having accepted "an invitation to design a world ...,” some 3400 men and women assembled in Washington for the 1971 White House Conference on Aging.

Issuing the invitation was JOHN B. MARTIN. '31, Commissioner on Aging in the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare and Special Assistant to the President for the Aging. As "ombudsman for older people," he regards the plight of the aging as an urgent issue.

"Instead of being rewarded in dignity for the contributions they made in their working years toward building the tremendous productive capacity of the nation," he wrote recently, "older Americans are in fact often regarded as nuisances to be tolerated, as charity patients—all our pious platitudes to the contrary."

The major obstacle to first-class citizenship for the aging, Martin believes, is a lack of national commitment. "In this great and affluent country, we can afford to dream dreams," he told conference delegates. "We can afford to have what we want to have. We can have an adequate retirement income, strengthened and comprehensive health care, more and better housing, chance for useful and constructive employment, and an array of needed social services. We can have them, that is, if as a nation we want them badly enough."

The White House Conference was planned as a frontal attack on the special burdens of privation and isolation which beset millions of aging Americans. Its theme was "Toward a National Policy on Aging," its goal "a design for achieving a satisfying future for all Americans."

Martin looks on the conference as a three-year continuum: the first stage a prologue of community forums and state-level conferences to define needs and map programs; the second the Washington meetings; and the third "the year of implementation."

Implementation will be an awesome task. More than 500 recommendations emerged from sessions on general subjects and specialized concerns. The preponderance dealt directly or indirectly with financial issues; minimum annual income, better pension plans, property tax relief, improvements in Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. Others called for a national health program and various personal services aimed at prolonging independence.

Commissioner Martin concurs in the emphasis on economic considerations. With 40% of the elderly either poor or near poor and 25% living in households below the poverty level, he contends that "the issue of more adequate income overshadows all the rest because it relates to all the other basic needs—good health care, satisfactory housing, proper nutrition, and convenient transportation." But he assigns second priority to "discrimination in opportunity—the lack of a role or welcome to active participation in life."

The Older Americans Act, which Martin administers, lays heavy stress on keeping the aging in the mainstream of life and using their accumulated experience for their own and society's benefit. It emphasizes—and funds—the Foster Grandparent Program and RSVP (Retired Senior Volunteer Program). The Commissioner is a vigorous adherent of cooperative programming with such groups as the Model Cities Administration. "I have never advocated establishment of a large number of new age-segregated services for the old only,” he emphasizes. "Instead I have asked for assurance that wherever there is a program for people, olderpeople are included in its planning, in its detailed design, and in a fair share of its services and opportunities—not the least of which is an opportunity to serve."

If the problems of aging are susceptible of solution, John Martin, who specialized early in conquering lofty challenges, is likely to solve them. In college, he was the man who was—and won—everything. Dartmouth's laurels—outstanding freshman award. Senior Fellowship, Phi Beta Kappa, Casque and Gauntlet, editorship of The Dartmouth, presidencies of Green Key, Palaeopitus, and his Class—were capped by a Rhodes Scholarship which took him to Oxford for two years before he entered law school at the University of Michigan. A successful law practice and elective offices in Michigan have been interspersed with federal government service before, during, and after World War II.

Martin's concern with the discrepancy between pretensions and performance in treatment of the elderly is no recent or sometime thing. He has headed state and local commissions in his native Michigan "and helped plan the 1961 White House Conference on Aging.

In response to a 25th reunion questionnaire about what he got from his college education, he wrote: "I think most of all it was the degree to which Dartmouth gave me an understanding of and a sympathy with my fellow men. That understanding and sympathy seem to me to be the essence of true education."

As Commissioner on Aging, John Martin is putting that understanding and that sympathy, plus his own innate talents, to work on an ironic by-product of American civilization—the problem of how to make worth living those extra years which scientific progress has bestowed upon its citizens.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureKiewit: A Man-Machine Success Story

April 1972 By Charles J. Kershner -

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

April 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

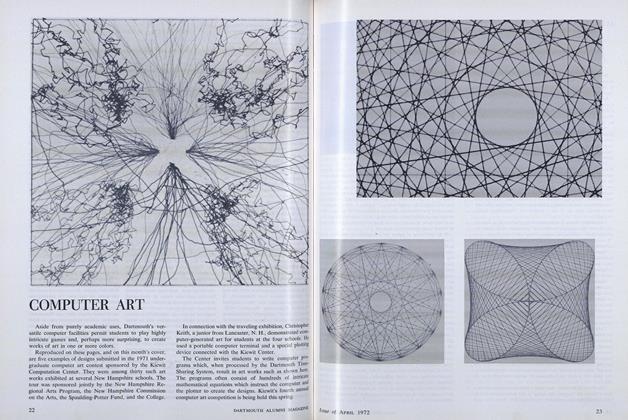

FeatureCOMPUTER ART

April 1972 -

Article

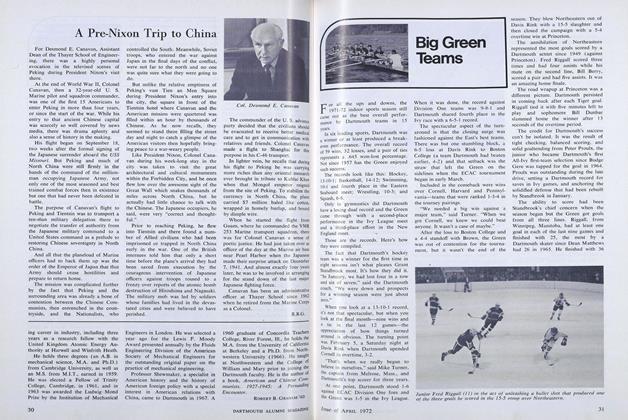

ArticleBig Green Teams

April 1972 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleFaculty

April 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleMaximum Return vs. Social Concern

April 1972

Features

-

Feature

FeatureRETIRING FACULTY

JUNE 1967 -

Feature

FeatureJOHN CAREY

Nov - Dec -

FEATURE

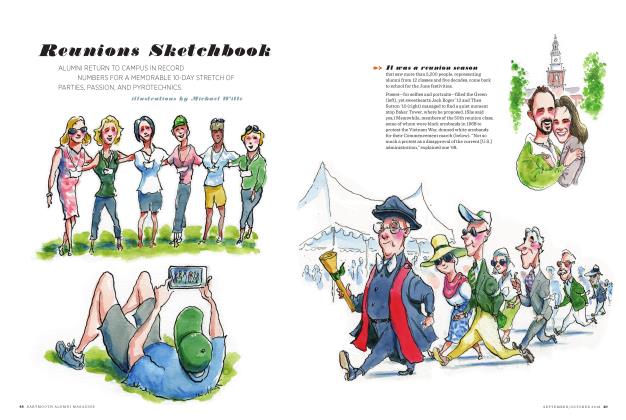

FEATUREReunions Sketchbook

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 -

FEATURES

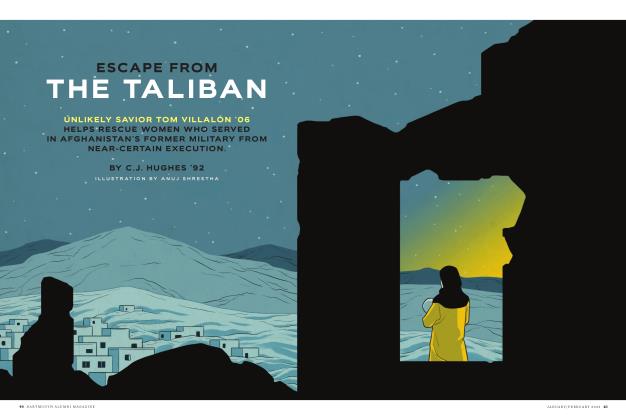

FEATURESEscape From the Taliban

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2023 By C.J. Hughes ’92 -

Cover Story

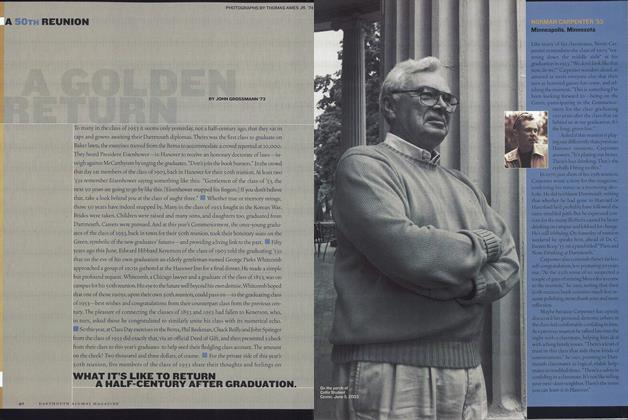

Cover StoryA Golden Return

Sept/Oct 2003 By JOHN GROSSMAN ’73 -

Feature

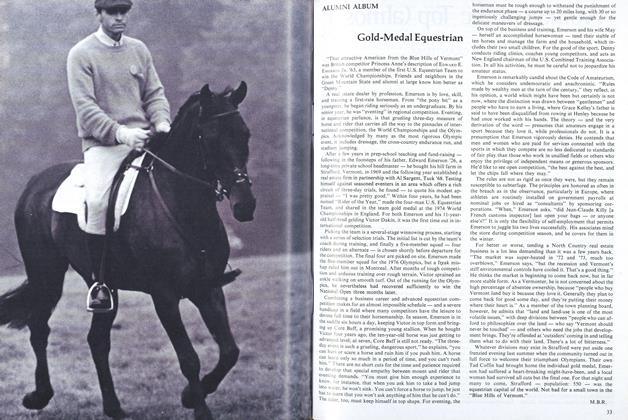

FeatureGold-Medal Equestrian

May 1977 By M.B.R.