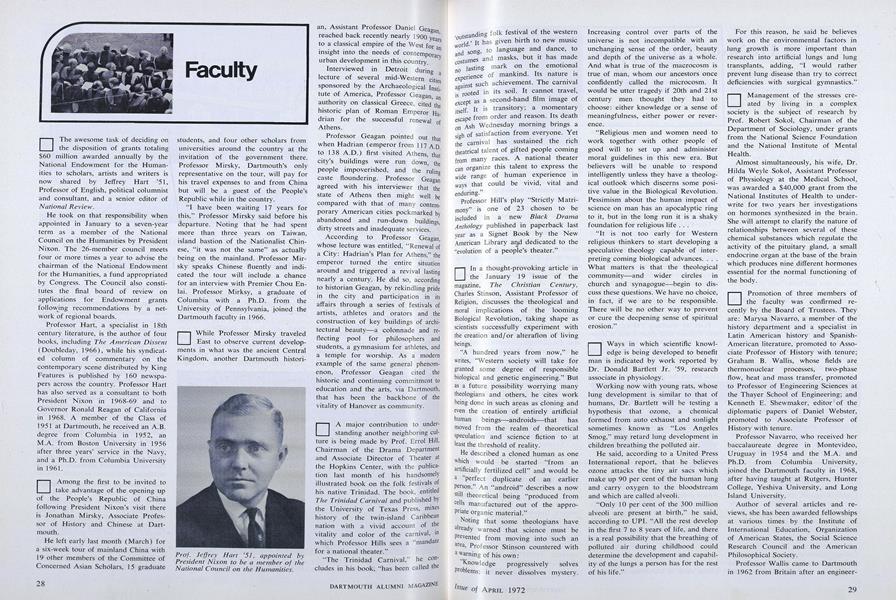

The awesome task of deciding on the disposition of grants totaling $6O million awarded annually by the National Endowment for the Humanities to scholars, artists and writers is now shared by Jeffrey Hart ’51, Professor of English, political columnist and consultant, and a senior editor of National Review.

He took on that responsibility when appointed in January to a seven-year term as a member of the National Council on the Humanities by President Nixon. The 26-member council meets four or more times a year to advise the chairman of the National Endowment for the Humanities, a fund appropriated by Congress. The Council also constitutes the final board of review on applications for Endowment grants following recommendations by a network of regional boards.

Professor Hart, a specialist in 18th century literature, is the author of four books, including The American Dissent (Doubleday, 1966), while his syndicated column of commentary on the contemporary scene distributed by King Features is published by 160 newspapers across the country. Professor Hart has also served as a consultant to both President Nixon in 1968-69 and to Governor Ronald Reagan of California in 1968. A member of the Class of 1951 at Dartmouth, he received an A.B. degree from Columbia in 1952, an M.A. from Boston University in 1956 after three years' service in the Navy, and a Ph.D. from Columbia University in 1961.

Among the first to be invited to take advantage of the opening up of the People's Republic of China following President Nixon's visit there is Jonathan Mirsky, Associate Professor of History and Chinese at Dartmouth.

He left early last month (March) for a six-week tour of mainland China with 19 other members of the Committee of Concerned Asian Scholars, 15 graduate students, and four other scholars from universities around the country at the invitation of the government there. Professor Mirsky, Dartmouth's only representative on the tour, will pay for his travel expenses to and from China but will be a guest of the People's Republic while in the country.

"I have been waiting 17 years for this," Professor Mirsky said before his departure. Noting that he had spent more than three years on Taiwan, island bastion of the Nationalist Chinese, "it was not the same" as actually being on the mainland. Professor Mirsky speaks Chinese fluently and indicated the tour will include a chance for an interview with Premier Chou Enlai. Professor Mirksy, a graduate of Columbia with a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania, joined the Dartmouth faculty in 1966.

While Professor Mirsky traveled East to observe current developments in what was the ancient Central Kingdom, another Dartmouth historian, Assistant Professor Daniel Geagan, reached back recently nearly 1900 years to a classical empire of the West for an insight into the needs of contemporary urban development in this country.

Interviewed in Detroit during a lecture of several mid-Western cities sponsored by the Archaeological Institute of America, Professor Geagan, an authority on classical Greece, cited the historic plan of Roman Emperor Hadrian for the successful renewal of Athens.

Professor Geagan pointed out that when Hadrian (emperor from 117 A.D. to 138 A.D.) first visited Athens, that city's buildings were run down, the people impoverished, and the ruling caste floundering. Professor Geagan agreed with his interviewer that the state of Athens then might well be compared with that of many contemporary American cities pockmarked by abandoned and run-down buildings, dirty streets and inadequate services.

According to Professor Geagan, whose lecture was entitled, "Renewal of a City: Hadrian's Plan for Athens," the emperor turned the entire situation around and triggered a revival lasting nearly a century. He did so, according to historian Geagan, by rekindling pride in the city and participation in its affairs through a series of festivals of artists, athletes and orators and the construction of key buildings of architectural beauty—a colonnade and reflecting pool for philosophers and students, a gymnasium for athletes, and a temple for worship. As a modern example of the same general phenomenon, Professor Geagan cited the historic and continuing commitment to education and the arts, via Dartmouth, that has been the backbone of the vitality of Hanover as community.

A major contribution to understanding another neighboring culture is being made by Prof. Errol Hill, Chairman of the Drama Department and Associate Director of Theater at the Hopkins Center, with the publication last month of his handsomely illustrated book on the folk festivals of his native Trinidad. The book, entitled The Trinidad Carnival and published by the University of Texas Press, mixes history of the twin-island Caribbean nation with a vivid account of the vitality and color of the carnival, in which Professor Hills sees a "mandate for a national theater."

"The Trinidad Carnival," he concludes in his book, "has been called the ‘outstanding folk festival of the western world.' It has given birth to new music and song, to language and dance, to costumes and masks, but it has made no lasting mark on the emotional experience of mankind. Its nature is against such achievement. The carnival is rooted in its soil. It cannot travel, except as a second-hand film image of itself. It is transitory; a momentary escape from order and reason. Its death on Ash Wednesday morning brings a sigh of satisfaction from everyone. Yet the carnival has sustained the rich theatrical talent of gifted people coming from many races. A national theater can organize this talent to express the wide range of human experience in ways that could be vivid, vital and enduring."

Professor Hill's play "Strictly Matrimony" is one of 23 chosen to be included in a new Black DramaAnthology published in paperback last year as a Signet Book by the New American Library and dedicated to the "evolution of a people's theater."

In a thought-provoking article in the January 19 issue of the magazine, The Christian Century, Charles Stinson, Assistant Professor of Religion, discusses the theological and moral implications of the looming Biological Revolution, taking shape as scientists successfully experiment with the creation and/or alteration of living beings.

"A hundred years from now," he writes, "Western society will take for granted some degree of responsible biological and genetic engineering." But as a future possibility worrying many theologians and others, he cites work being done in such areas as cloning and even the creation of entirely artificial human beings—androids—that has moved from the realm of theoretical speculation and science fiction to at least the threshold of reality.

He described a cloned human as one which would be started "from an artificially fertilized cell" and would be a "perfect duplicate of an earlier person." An "android" describes a now still theoretical being "produced from cells manufactured out of the appropriate organic material."

Noting that some theologians have already warned that science must be Prevented from moving into such an area, Professor Stinson countered with a warning of his own:

“Knowledge progressively solves Problems; it never dissolves mystery. Increasing control over parts of the universe is not incompatible with an unchanging sense of the order, beauty and depth of the universe as a whole. And what is true of the macrocosm is true of man, whom our ancestors once confidently called the microcosm. It would be utter tragedy if 20th and 21st century men thought they had to choose: either knowledge or a sense of meaningfulness, either power or reverence.

"Religious men and women need to work together with other people of good will to set up and administer moral guidelines in this new era. But believers will be unable to respond intelligently unless they have a theological outlook which discerns some positive value in the Biological Revolution. Pessimism about the human impact of science on man has an apocalyptic ring to it, but in the long run it is a shaky foundation for religious life...

"It is not too early for Western religious thinkers to start developing a speculative theology capable of interpreting coming biological advances.... What matters is that the theological community—and wider circles in church and synagogue—begin to discuss these questions. We have no choice, in fact, if we are to be responsible. There will be no other way to prevent or cure the deepening sense of spiritual erosion."

Ways in which scientific knowledge is being developed to benefit man is indicated by work reported by Dr. Donald Bartlett Jr. '59, research associate in physiology.

Working now with young rats, whose lung development is similar to that of humans, Dr. Bartlett will be testing a hypothesis that ozone, a chemical formed from auto exhaust and sunlight sometimes known as "Los Angeles Smog," may retard lung development in children breathing the polluted air.

He said, according to a United Press International report, that he believes ozone attacks the tiny air sacs which make up 90 per cent of the human lung and carry oxygen to the bloodstream and which are called alveoli.

"Only 10 per cent of the 300 million alveoli are present at birth," he said, according to UPI. "All the rest develop in the first 7 to 8 years of life, and there is a real possibility that the breathing of polluted air during childhood could determine the development and capability of the lungs a person has for the rest of his life."

For this reason, he said he believes work on the environmental factors in lung growth is more important than research into artificial lungs and lung transplants, adding, "I would rather prevent lung disease than try to correct deficiencies with surgical gymnastics."

Management of the stresses created by living in a complex society is the subject of research by Prof. Robert Sokol, Chairman of the Department of Sociology, under grants from the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Mental Health.

Almost simultaneously, his wife, Dr. Hilda Weyle Sokol, Assistant Professor of Physiology at the Medical School, was awarded a $40,000 grant from the National Institutes of Health to underwrite for two years her investigations on hormones synthesized in the brain. She will attempt to clarify the nature of relationships between several of these chemical substances which regulate the activity of the pituitary gland, a small endocrine organ at the base of the brain which produces nine different hormones essential for the normal functioning of the body.

Promotion of three members of the faculty was confirmed recently by the Board of Trustees. They are: Marysa Navarro, a member of the history department and a specialist in Latin American history and Spanish- American literature, promoted to Associate Professor of History with tenure; Graham B. Wallis, whose fields are thermonuclear processes, two-phase flow, heat and mass transfer, promoted to Professor of Engineering Sciences at the Thayer School of Engineering; and Kenneth E. Shewmaker, editor of the diplomatic papers of Daniel Webster, promoted to Associate Professor of History with tenure.

Professor Navarro, who received her baccalaureate degree in Montevideo. Uruguay in 1954 and the M.A. and Ph.D. from Columbia University, joined the Dartmouth faculty in 1968, after having taught at Rutgers, Hunter College, Yeshiva University, and Long Island University.

Author of several articles and reviews, she has been awarded fellowships at various times by the Institute of International Education, Organization of American States, the Social Science Research Council and the American Philosophical Society.

Professor Wallis came to Dartmouth in 1962 from Britain after an engineering career in industry, including three years as a research fellow with the United Kingdom Atomic Energy Authority at Harwell and Winfrith Heath.

He holds three degrees (an A.B. in mechanical science, MA. and Ph.D.) from Cambridge University, as well as an M.S. from M.I.T., earned in 1959. He was elected a Fellow of Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1961, and in 1963 was awarded the Ludwig Mond Prize by the Institution of Mechanical Engineers in London. He was selected a year ago for the Lewis F. Moody Award presented annually by the Fluids Engineering Division of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers for the outstanding original paper on the practice of mechanical engineering.

Professor Shewmaker, a specialist in American history and the history of American foreign policy with a special interest in American relations with China, came to Dartmouth in 1967. A 1960 graduate of Concordia Teachers College, River Forest, Ill., he holds the M.A. from the University of California at Berkeley and a Ph.D. from Northwestern University (1966). He taught at Northwestern and the College of William and Mary prior to joining the Dartmouth faculty. He is the author of a book, American and Chinese Communists, 1927-1945: A PersuadingEncounter.

Prof. Jeffrey Hart '51, appointed byPresident Nixon to be a member of theNational Council on the Humanities.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureKiewit: A Man-Machine Success Story

April 1972 By Charles J. Kershner -

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

April 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureAdvocate for the Aging

April 1972 -

Feature

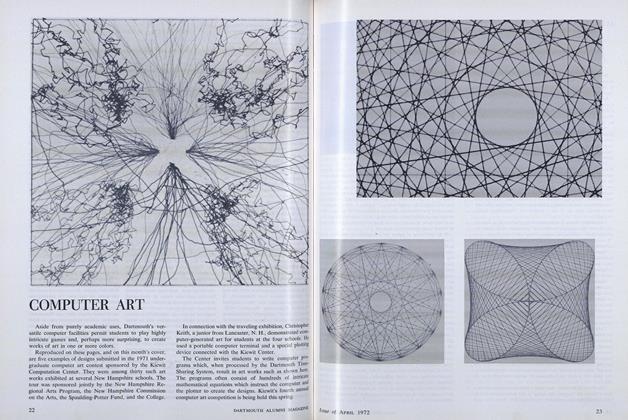

FeatureCOMPUTER ART

April 1972 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

April 1972 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleMaximum Return vs. Social Concern

April 1972

ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

-

Article

ArticleFaculty

NOVEMBER 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

DECEMBER 1971 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

MAY 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

DECEMBER 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureDartmouth Gives Its Name to U.S.—Soviet Understanding

FEBRUARY 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

APRIL 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

Article

-

Article

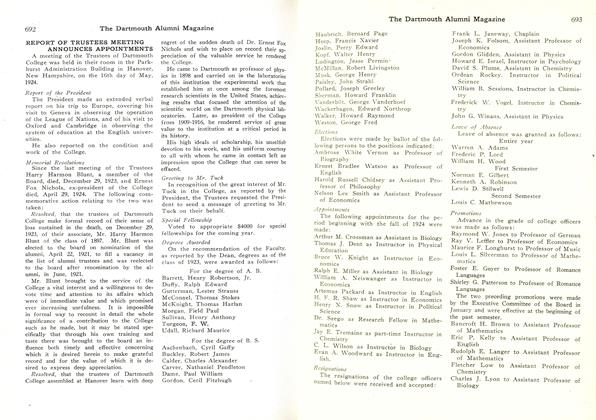

ArticleGreeting to Mr. Tuck

June 1924 -

Article

ArticleTHE ATHLETIC COUNCIL

JULY 1931 -

Article

ArticleA SPRING STREAM

APRIL 1932 -

Article

ArticleFreshman-Sophomore Reading Program

OCTOBER 1958 -

Article

ArticleFOUNDATIONS & CORPORATIONS

OCTOBER • 1986 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH'S PART IN UPBUILDING PHILLIPS ANDOVER ACADEMY

January 1918 By James Fairbanks Colby '72