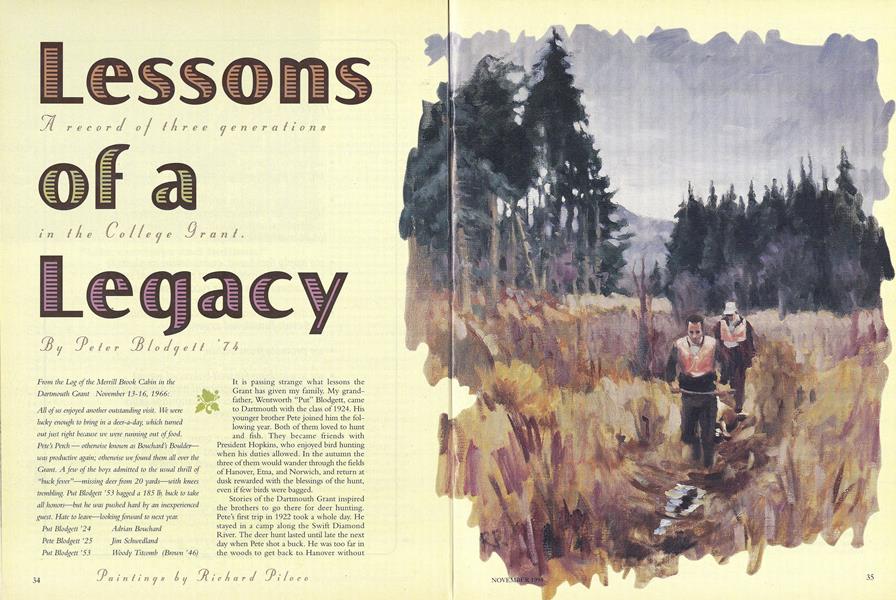

A record of three qenerations in the College grant

From the Log of the Merrill Brook Cabin in theDartmouth Grant November 13-16, 1966:

All of us enjoyed another outstanding visit. We were . 1lucky enough to bring in a deer-a-day, which turnedout just right because we were running out of food.Pete's Perch otherwise known as Bouchard's Boulderwas productive again; otherwise we found them all over theGrant. A few of the boys admitted to the usual thrill of"buck fever"—missing deer from 20 yards—with kneestrembling. Put Blodgett '53 bagged a 185 lb. buck to takeall honors—but he was pushed hard by an inexperiencedguest. Hate to leave—looking forward to next year.

Put Blodgett '24 Pete Blodgett '25 Put Blodgett '53 Adrian BouchardJim SchwedlandWoody Titcomb (Broum '46)

It is passing strange what lessons the Grant has given my family. My grandfather, Wentworth "Put" Blodgett, came to Dartmouth with the class of 1924. His younger brother Pete joined him the following year. Both of them loved to hunt and fish. They became friends with President Hopkins, who enjoyed bird hunting when his duties allowed. In the autumn the three of them would wander through the fields of Hanover, Etna, and Norwich, and return at dusk rewarded with the blessings of the hunt, even if few birds were bagged.

Stories of the Dartmouth Grant inspired the brothers to go there for deer hunting. Pete's first trip in 1922 took a whole day. He stayed in a camp along the Swift Diamond River. The deer hunt lasted until late the next day when Pete shot a buck. He was too far in the woods to get back to Hanover without missing a day of classes. He cut class and brought the deer back the next day. He found a note from the dean posted on his door. The policy for cutting classes was strict—after three unexcused cuts a student could be dismissed. Dean Craven Laycock was known for his toughness. Pete was in trouble.

In the Dean's Office, Pete was told to explain the reason for his absence from classes. He said, "I was in the Dartmouth Grant deer hunting. It was late in the day when I shot a buck over Windey Ridge. I dressed him out but could not get the deer back to camp before dark. What should I do? Leave the deer and return to Hanover in time to attend class? Or wait until morning to bring back the deer and face the consequences? What would you have done, Dean Laycock?"

The dean smiled and said, "That's a new one on me, Mr. Blodgett. You are excused from missing class. And I hope that deer tastes as good as your story sounds!" The next day a venison steak was delivered to the dean's house.

In 1922 there were no College cabins in the Grant, only some logging camps filled with loggers who slept two to a bunk and ate breakfast in five minutes to be out in the woods on time. At night the camps were hot, almost suffocating. Once, Pete opened a door to let in some fresh cool air. "Shut the goddamned door," he heard. He tried a conversation at breakfast. The men grunted and kept shoveling down the food. The boss got up in three and a half minutes; the loggers knew they had to be close behind. Pete spent just one night with loggers.

Some part of the Northcountry took root in the brothers, changed them. After graduation my grand- father went west to help survey the Olympic Peninsula, the last remaining unsurveyed section of the lower forty- eight. Pete flew one of the first planes across the United States to Alaska in order to hunt and fish and film the wildlife of the North. He brought back the first color films of salmon and the Kodiak bear, which were later shown at colleges and clubs around the East.

In 1934 Put moved his family from Boston to Bradford, Vermont. He had looked all over New England but felt drawn to the Upper Valley. In Bradford he had found a farm through which several brooks ran. In one of the brooks he could see trout. Inspecting the spring, he saw deer tracks, and he knew he had found his home.

Over the decades his farm grew, as did his son, my father, Putnam Blodgett. He graduated from Dartmouth in 1953. Like his father and his uncle, my father was drawn to wild places. One summer he drove a Model A Ford from Hanover across Canada and up the Alaskan Highway. He made regular trips to the Grant.

Dad was married in 1952, and I was the class baby, arriving in March the following year. When my father graduated he took over running the farm, and began at Tuck School. The commute to Hanover was more than 20 miles each way, and milking had to be done before he left for classes. My sister arrived the following May, and the farm took over all of my father's attention. He worked hard, treated the land like a steward. I grew up surrounded by woods and meadows, cows and trout, traps and chores and wooden boats. In the mid fifties my father joined his father and his Uncle Pete on their deer hunting trips to the Grant. One time Dad returned with a beard, and I remember that I decided then that someday I, too, would have a beard.

From the Log, November 9, 1976:

If there were deer all over the Grant, even one for everyhundred square yards, but each man had to come here alone,none of us would come. If there were only one deer in the wholeGrant, but we could hunt with this gang, we would still comegladly. What conversation! What memories are invoked! Thiswas a convocation of the world's best storytellers, cooks, and bottle-washers, whittlers, and bear tallow boot grease makers.

Have seen the deer a little thicker, but can't complain.Four does and two bears, including Bouchard's first bruin,which he shot only after a long philosophical discussion withhimself.

A good week; may there be many more.

In the mid sixties Dad developed a boys camp where his aim was to teach boys the wilderness skills of camping, cooking over a fire, canoeing, hiking, swimming, fishing, and riflery, along with providing the adventure of trips to the great mountain ranges and rivers of the Northeast. For 20 years my father taught boys how to respect and appreciate the north woods and streams. Alongside the campers I learned how to cook with birchbark containers and create a shelter for a night. With my father I have hiked all over New England and paddled the region's calm and wild waters.

From the Log, November 13-16, 1987:

Up for a few days of deer hunting. We saw 9 does and onebuck. Dave got a shot at the buck. Good food and good company. The deer will be bigger next year.

I have seen changes in these men over the last 20 years. My father was once a great hunter who would follow a track for ten hours, shoot his deer, and then spend another four hours dragging it back to camp. Sometimes he would keep a deer moving all day by trotting along its track. After 30 years of almost always getting his deer, though, his desire to hunt waned. The need for meat, hide, and horns diminished. Yet he still would come to the Grant. Together he and I would strive for a peak or a lake that he had not seen in years.

Several years ago we tried to reach the summit of Magalloway Mountain north of the Grant. The weather was cold and snow-blown. We drove to the end of a log- ging road, then disappeared into the woods on a bush- whack north. A blizzard wrapped around us. We came upon a moose track going in our direction and followed it. We reached the height of land, and Dad said, This is when we might see something. We're downwind and coming over the ridge. Keep your eyes open.

We hiked silently over the top. The moose sprang from its bed, the snow cascading from its back. It was like watching the earth shudder, rise, and shuffle into the wavering white walls of the storm. In the footsteps of my father I felt a direct connection with the past. This moment has been an abiding truth between generations of fathers and sons. The moose shambled away, leaving me in the shocked silence of awe, leaving me to wonder who in the encounter was the more surprised. In a blizzard, without witness, this ceremony appeared and disappeared like a vision. A truth shrouded in silence and wrapped in snow haunts me still.

From the Log, November 16-18, 1990

After a couple of years exploring the Upper Grant fromHellgate Gorge during deer season, we are grateful to be back atMerrill Brook. Put Blodgett '53 remembers being in theMerrill Brook Cabin the first deer season after the cabin wasbuilt in 1960. Legendary hunters and legendary woodsmenhave all left their mark through the years on this annual pilgrimage.

Adrian Bouchard, Bill Robes, Al Merrill, Put Blodgett'24 are now released from this earthly existence but they areremembered and honored whenever we gather here. Year byyear, the layers of adventure join in a seamless drift that each ofus carries beyond the boundaries of this special realm .

Sixteen inches of snow has hardened under rainfall (Sat.)to a tough crust, noisy and tiring. Fresh snow powdered theGrant for Sunday morning to help the trackers. As of this writing no deer in camp and daylight is dwindling. Heading hometomorrow.

A hunting camp on Martha's Vineyard that Pete bought with friends in the thirties was donated to the Massachusetts Trustees of Reservations so that a portion of wildness will remain on the Cape. Working with the Connecticut Watershed Council, Dad has helped preserve the undeveloped shoreline of Pout Pond in Lyme, New Hampshire. The pond he built (once known as Put's Puddle) for the boys camp in Bradford has also been saved from any development, and the camp continues to teach the wonders of living with a respect for wilderness.

From the Log, November 11-14, 1992:

In 1992 my great uncle Pete Blodgett came to the Grant tocelebrate his seventieth anniversary of deer hunting at theGrant. It is the fall of his eighty-ninth year. The deer are hardto see, let alone shoot, this year. In our time here only one deeris hanging in the Grant (at the Management Center). Insteadof deer we have been busy counting memories of thisplace. ...Laughter, arguments on how to cook everything; storiesof deer, fish, Alaska, Arctic canoe trips, Iceland, Arizona, elk,moose, New Brunswick, Scottish Salmon, golden trout,Kodiak bears, coyotes, rabbits, pine martin, fishers, lynx, collegedays, good Deans and bad ones; good college Presidents andnot-so-good ones; loons, beavers, porcupines, crows, jays, ravensand always the abiding places of the Grant.

Every place has its own story. Each cabin, every brook,ridge, and valley all bring back associationsfrom adventures past. The seasons andcycles begin to be seen. The coyotes comeand they go. The deer are thick and thenthin. The moose returns. Logging comesand goes. Bridges are built and are washedaway.

Another grand year at the Grant. Theend of an era.

After a long dark drive I reach the cabin. Will is on the porch to greet me. The serious hunters, including my brother, are all asleep, but Dad has saved some supper of beanhole beans which are out of this world.

Mike and my Great-Uncle Pete are swapping stories and jokes. Dad is at ease. Jack Noon is his friendly, affable self. I feel that time itself has gently stopped, and this hunting season melts into all the hunting seasons before. Old pictures of deer hanging from the cabin are passed hand to hand and the tales told grow bolder and more incredible with each telling. Uncle Pete gazes into the fire as he remembers people, places and adventures from 70 seasons in the Grant.

Outside in the moonlight the clouds race by. Some come here every year to hunt the deer. They have a dream: to seek, find, and bring home meat and memories. I come here every year to hunt my dreams: to seek, find, and bring home meaning and memories. I come here like my father and his father before him to learn to see, to feel some glimmer from the wild heart of the world. To wander all day out of sight and sound of the human tribe, to briefly connect with the rhythm and rhyme of the North Woods.

I must pay attention. The gifts are given so quickly—the northern lights quivering in the midnight sky, a partridge feeding, a fish leaping downstream against the sky.

Through a passage of years I have earned a place in a company ot men who love the natural world and especially this small corner of it.

A life can be measured in the number of visits to the Grant.

Inspecting the spring, he sawdeer tracks,and he knew hehad found his home.

J feel that time itself has gently stopped, and this hunting season melts into all the hunting seasons before.

PetePeter Blodgett is the town librarian forThetford, Vermont.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryYou Thougnt Rotc was Dead?

November 1994 By Frederic J. Frommer -

Cover Story

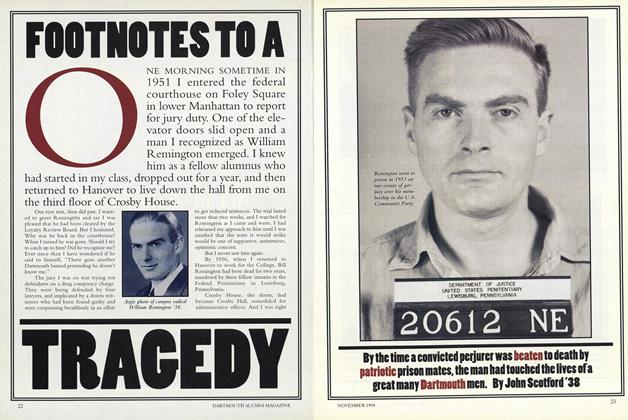

Cover StoryFOOTNOTES TO A TRAGEDY

November 1994 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

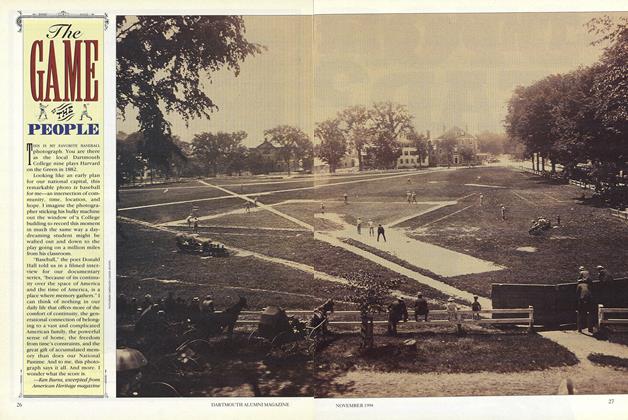

FeatureTHE GAME PEOPLE

November 1994 By Ken Burns -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

November 1994 By Daniel Zenkel -

Article

ArticleEssayists and Solitude

November 1994 By James O. Freedman -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

November 1994 By "E. Wheelock"

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCONVOCATION ON THE ARTS

DECEMBER 1962 -

Cover Story

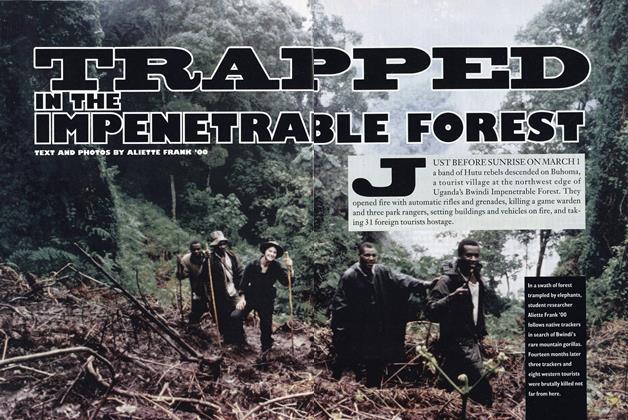

Cover StoryTrapped in the Bwindi Impenetrable Forest

MAY 1999 By ALIETTE FRANK '00 -

Feature

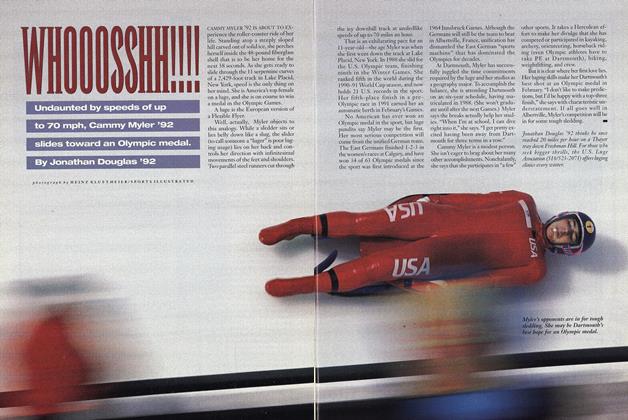

FeatureWHOOOSSHH!!!!

December 1991 By Jonathan Douglas '92 -

Feature

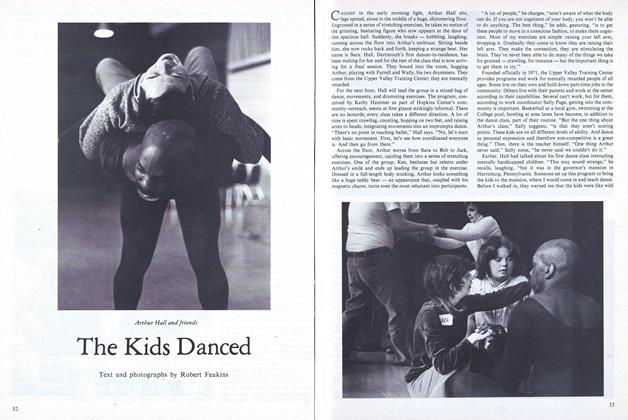

FeatureThe Kids Danced

September 1979 By Robert Feakins -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCROSSROADS

DECEMBER 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature"As Active As They Are Bright"

June 1961 By THADDEUS SEYMOUR