One hundred years have gone by since that afternoon in 1872 when Yale and Columbia played the first football game between Ivy League colleges. Yale won, 3-0. Since then, the eight Ivy colleges have peopled the football world with legendary figures, including Sid Luckman, Lou Kusserow, Gene Rossides, and Mike Pyszczymucha (Columbia), Pudge Heffelfinger, Albie Booth, Dink Stover, and Frank Merriwell (Yale). Merriwell, whose heroic performances are now limited to the Elysian Fields, will still talk football with anyone. Not long ago he took part in a dialogue with the shade of Quentin Compson III, a melancholy, suicidal youth who spent a year at Harvard in William Faulkner's The Sound and the Fury and Absalom, Absalom! As Ivy League football moves into its second century, excerpts from the Compson-Merriwell exchange may prove enlightening.

Compson: Why should eight teaching and research universities invest large amounts of time and money in a game played with an oblong ball? Is it really worth it? Why does anyone watch it?

Merriwell: Quentin, I'm afraid you're ragging me.

Compson: Not at all. The case against the sport is clear enough. Football is a violent game which finds its appeal in the basest human emotions. Despite its sanctimonious public stance, Ivy League football is no different from any other football in its intense emphasis on winning as the only thing. The recruiting of high school players by representatives of universities amounts to a group hypocrisy. Alumni are encouraged to relate to the university, not through its substantial intellectual achievements, but through the exploits of its football team. Preposterous! Social scientists long ago dispensed with the notion that manly combat builds any more character than a chess game.

Merriwell: I should gladly test that proposition against any of your social scientists nose to nose, on the gridiron. Forgive me for asking, Quentin, but did you ever attend a football game?

Compson: I have heard reports. Massive traffic jams before and after the contest. Seat locations immediately in front of an inebriated student, or behind a phalanx of comatose alumni. I believe that even the enthusiasts inevitably concur that the caliber of play on the field brings dishonor to the sport. The athletes themselves are impersonal, faceless machines, garbed in medieval armor. They are outfitted and huckstered like professionals, although they play less adroitly.

Merriwell: In contrast to the professional game, Ivy League football offers an afternoon full of interesting minor surprises - the pass dropped, the missed extra point, the extraordinary catch. Unlike baseball, it is the complete team sport. Twenty-two players move at one instant; if one does not fulfill his assignment, the play is a failure. There is an everpresent element of dramatic tension: eleven men endeavoring to move the ball across a line at the end of the field, eleven other men charged with stopping the advance. The action is circumscribed by a rigid structure of downs and time-outs, all serving to heighten the sense of drama and anticipation.

Compson: All this in light, freezing rain

Merriwell: Only partially so. There is a rhythm to the football season that puts one in touch with the larger rhythms of nature itself. The season, opens in summer and shirtsleeves. Then a game or two played before sweaters and topcoats, an eerie Indian summer game, and at last the resolute march into the chills and damps of November. Indeed, games are not infrequently played on pristine fall days, redolent with the smell of burning leaves.

Compson: Despite local ordinances.

Merriwell: Football is all this and more. It is freshmen on their first dates, a tweed coat removed from summer's mothballs, lunch with old friends before the game, the long walk back to the car. And the silent satisfaction of reading the Sunday sports pages, knowing that you had the real story.

For an athlete, it is emotion so intense that he will not feel its like again. A chance to test himself against unknown challenges. A public show of excellence. Football is the final outdoor ritual of the year, and with the end of its combats come the long shadows and the descent of winter.

Compson (absently): Drowned in the fading of honeysuckle.

Merrwell: Like to have a catch?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBetting man's choice: Dartmouth. Then Harvard, Columbia, Cornell

October 1972 -

Feature

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

October 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

October 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureHanover's "Host with the Most"

October 1972 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

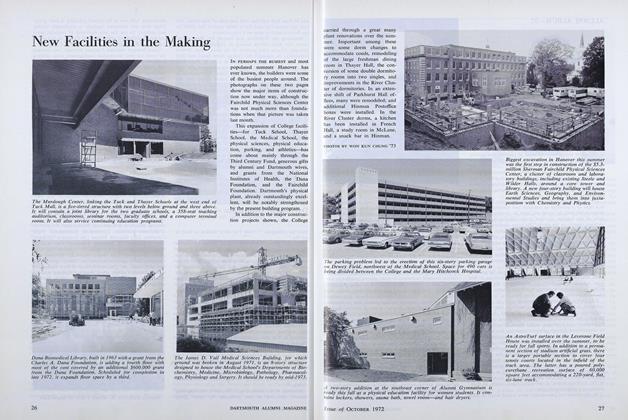

FeatureNew Facilities in the Making

October 1972 -

Feature

FeatureIvy League bands: The beat goes on

October 1972

Features

-

Feature

FeaturePrelude to a Third Century

NOVEMBER 1964 -

Feature

FeatureReunions Draw Big Turnouts

JULY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureM.S. Candidate

MARCH 1967 -

Cover Story

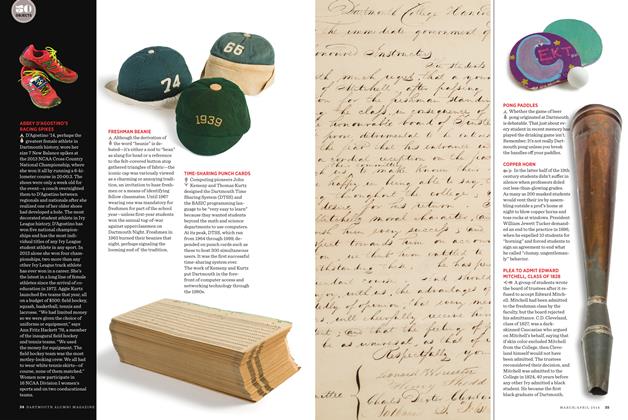

Cover StoryCOPPER HORN

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERPROMISE AND OVERDELIVER

OCTOBER 1990 By William H. Davidow '57 -

Feature

FeatureONE PLUS ONE EQUALS THREE

MAY | JUNE 2014 By Yuki Kondo-Shah ’07