The College pays a debtto the Indian tribe that stronglyinfluenced its Hanover location

RESEARCH ASSOCIATE IN ANTHROPOLOGY

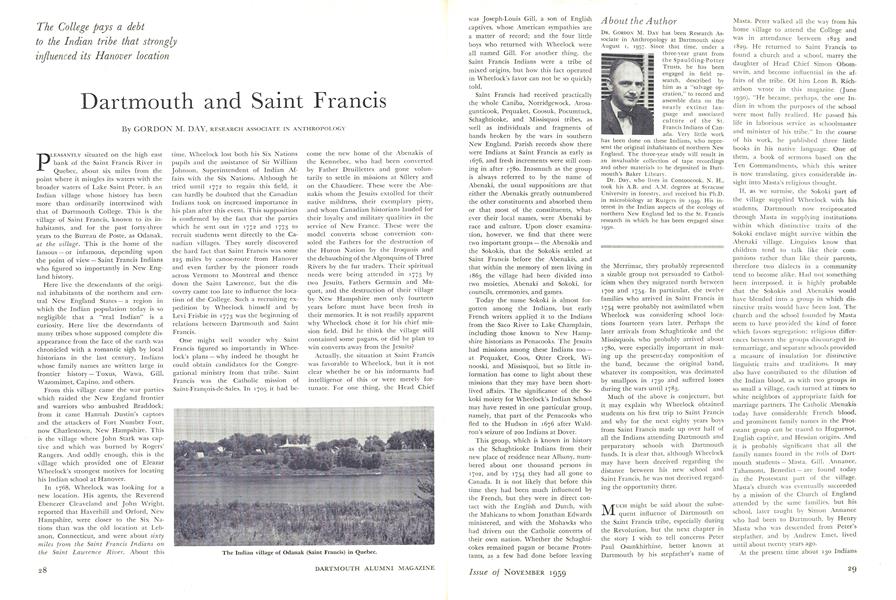

PLEASANTLY situated on the high east bank of the Saint Francis River in Quebec, about six miles from the point where it mingles its waters with the broader waters of Lake Saint Peter, is an Indian village whose history has been more than ordinarily intertwined with that of Dartmouth College. This is the village of Saint Francis, known to its inhabitants, and for the past forty-three years to the Bureau de Poste, as Odanak, at the village. This is the home of the famous — or infamous, depending upon the point of view - Saint Francis Indians who figured so importantly in New England history.

Here live the descendants of the original inhabitants of the northern and central New England States - a region in which the Indian population today is so negligible that a "real Indian" is a curiosity. Here live the descendants of many tribes whose supposed complete disappearance from the face of the earth was chronicled with a romantic sigh by local historians in the last century, Indians whose family names are written large in frontier history - Toxus, Wawa, Gill, Wazomimet, Capino, and others.

From this village came the war parties which raided the New England frontier and warriors who ambushed Braddock; from it came Hannah Dustin's captors and the attackers of Fort Number Four, now Charlestown, New Hampshire. This is the village where John Stark was captive and which was burned by Rogers' Rangers. And oddly enough, this is the village which provided one of Eleazar Wheelock's strongest motives for locating his Indian school at Hanover.

In 1768, Wheelock was looking for a new location. His agents, the Reverend Ebenezer Cleaveland and John Wright, reported that Haverhill and Orford, New Hampshire, were closer to the Six Nations than was the old location at Lebanon, Connecticut, and were about sixtymiles from the Saint Francis Indians onthe Saint Lawrence River. About this time, Wheelock lost both his Six Nations pupils and the assistance of Sir William Johnson, Superintendent of Indian Affairs with the Six Nations. Although he tried until 1772 to regain this field, it can hardly be doubted that the Canadian Indians took on increased importance in his plan after this event. This supposition is confirmed by the fact that the parties which he sent out in 1772 and 1773 to recruit students went directly to the Canadian villages. They surely discovered the hard fact that Saint Francis was some 225 miles by canoe-route from Hanover and even farther by the pioneer roads across Vermont to Montreal and thence down the Saint Lawrence, but the discovery came too late to influence the location of the College. Such a recruiting expedition by Wheelock himself and by Levi Frisbie in 1773 was the beginning of relations between Dartmouth and Saint Francis.

One might well wonder why Saint Francis figured so importantly in Wheelock's plans - why indeed he thought he could obtain candidates for the Congregational ministry from that tribe. Saint Francis was the Catholic mission of Sain-François-de-sales. In 1705 it had become the new home of the Abenakis of the Kennebec, who had been converted by Father Druillettes and gone voluntarily to settle in missions at Sillery and on the Chaudiere. These were the Abenakis whom the Jesuits extolled for their native mildness, their exemplary piety, and whom Canadian historians lauded for their loyalty and military qualities in the service of New France. These were the model converts whose conversion consoled the Fathers for the destruction of the Huron Nation by the Iroquois and the debauching of the Algonquins of Three Rivers by the fur traders. Their spiritual needs were being attended in 1773 by two Jesuits, Fathers Germain and Maquet, and the destruction of their village by New Hampshire men only fourteen years before must have been fresh in their memories. It is not readily apparent why Wheelock chose it for his chief mission field. Did he think the village still contained some pagans, or did he plan to win converts away from the Jesuits?

Actually, the situation at Saint Francis was favorable to Wheelock, but it is not clear whether he or his informants had intelligence of this or were merely fortunate. For one thing, the Head Chief was Joseph-Louis Gill, a son of English captives, whose American sympathies are a matter of record; and the four little boys who returned with Wheelock were all named Gill. For another thing, the Saint Francis Indians were a tribe of mixed origins, but how this fact operated in Wheelock's favor can not be so quickly told.

Saint Francis had received practically the whole Caniba, Norridgewock, Arosagunticook, Pequaket, Coosuk, Pocumtuck, Schaghticoke, and Missisquoi tribes, as well as individuals and fragments of bands broken by the wars in southern New England. Parish records show there were Indians at Saint Francis as early as 1676, and fresh increments were still coming in after 1780. Inasmuch as the group is always referred to by the name of Abenaki, the usual suppositions are that either the Abenakis greatly outnumbered the other constituents and absorbed them or that most of the constituents, whatever their local names, were Abenaki by race and culture. Upon closer examination, however, we find that there were two important groups - the Abenakis and the Sokokis, that the Sokokis settled at Saint Francis before the Abenakis, and that within the memory of men living in 1865 the village had been divided into two moieties, Abenaki and Sokoki, for councils, ceremonies, and games.

Today the name Sokoki is almost forgotten among the Indians, but early French writers applied it to the Indians from the Saco River to Lake Champlain, including those known to New Hampshire historians as Penacooks. The Jesuits had missions among these Indians too at Pequaket, Coos, Otter Creek, Winooski, and Missisquoi, but so little information has come to light about these missions that they may have been short-lived affairs. The significance of the Sokoki moiety for Wheelock's Indian School may have rested in one particular group, namely, that part of the Penacooks who fled to the Hudson in 1676 after Waldron's seizure of 200 Indians at Dover.

This group, which is known in history as the Schaghticoke Indians from their new place of residence near Albany, numbered about one thousand persons in 1702, and by 1754 they had all gone to Canada. It is not likely that before this time they had been much influenced by the French, but they were in direct contact with the English and Dutch, with the Mahicans to whom Jonathan Edwards ministered, and with the Mohawks who had driven out the Catholic converts of their own nation. Whether the Schaghticokes remained pagan or became Protestants, as a few had done before leaving the Merrimac, they probably represented a sizable group not persuaded to Catholicism when they migrated north between 1702 and 1754. In particular, the twelve families who arrived in Saint Francis in 1754 were probably not assimilated when Wheelock was considering school locations fourteen years later. Perhaps the later arrivals from Schaghticoke and the Missisquois, who probably arrived about 1780, were especially important in making up the present-day composition of the band, because the original band, whatever its composition, was decimated by smallpox in 1730 and suffered losses during the wars until 1783.

Much of the above is conjecture, but it may explain why Wheelock obtained students on his first trip to Saint Francis and why for the next eighty years boys from Saint Francis made up over half of all the Indians attending Dartmouth and preparatory schools with Dartmouth funds. It is clear that, although Wheelock may have been deceived regarding the distance between his new school and Saint Francis, he was not deceived regarding the opportunity there.

MUCH might be said about the subsequent influence of Dartmouth on the Saint Francis tribe, especially during the Revolution, but the next chapter in the story I wish to tell concerns Peter Paul Osunkhirhine, better known at Dartmouth by his stepfather’s name of Masta. Peter walked all the way from his home village to attend the College and was in attendance between 1823 and 1829. He returned to Saint Francis to found a church and a school, marry the daughter of Head Chief Simon Obomsawin, and become influential in the affairs of the tribe. Of him Leon B. Richardson wrote in this magazine (June 1930), "He became, perhaps, the one Indian in whom the purposes of the school were most fully realized. He passed his life in laborious service as schoolmaster and minister of his tribe." In the course of his work, he published three little books in his native language. One of them, a book of sermons based on the Ten Commandments, which this writer is now translating, gives considerable insight into Masta's religious thought.

If, as we surmise, the Sokoki part of the village supplied Wheelock with his students, Dartmouth now reciprocated through Masta in supplying institutions within which distinctive traits of the Sokoki enclave might survive within the Abenaki village. Linguists know that children tend to talk like their companions rather than like their parents, therefore two dialects in a community tend to become alike. Had not something been interposed, it is highly probable that the Sokokis and Abenakis would have blended into a group in which distinctive traits would have been lost. The church and the school founded by Masta seem to have provided the kind of force which favors segregation; religious differences between the groups discouraged intermarriage, and separate schools provided a measure of insulation for distinctive linguistic traits and traditions. It may also have contributed to the dilution of the Indian blood, as with two groups in so small a village, each turned at times to white neighbors of appropriate faith for marriage partners. The Catholic Abenakis today have considerable French blood, and prominent family names in the Protestant group can be traced to Huguenot, English captive, and Hessian origins. And it is probably significant that all the family names found in the rolls of Dartmouth students - Masta, Gill, Annance, Tahamont, Benedict - are found today in the Protestant part of the village. Masta's church was eventually succeeded by a mission of the Church of England attended by the same families, but his school, later taught by Simon Annance who had been to Dartmouth, by Henry Masta who was descended from Peter's stepfather, and by Andrew Emet, lived until about twenty years ago.

At the present time about 130 Indians live at Saint Francis, but the band numbers over 500 registered members. There is in addition a sizable number of persons of Saint Francis descent who have given up formal connections with the band and live in other parts of Quebec, in Ontario, and in the Northeastern States, often not known as Indians by their neighbors. In all this number there remain only about fifty persons who can speak the native language fluently. The native speakers are mostly over 65 years of age, and with few exceptions the children are not learning the language. The language, like the people, is called Abenaki, but this name may prove to be more convenient than accurate. It may prove to be essentially the speech of the Sokokis, or it may be an Abenaki dialect from the Androscoggin from which comparative, family-oriented studies may be able to identify Sokoki or Penacook traits.

The village itself has a modern look, and the Indians' conventional attire will disappoint the one who expects to find Wanalancet in full regalia. The number who earn their living by traditional Indian pursuits such as guiding are becoming fewer each year. Nevertheless, the lover of the primitive will find much of interest in the native dances, the language, and the native lore which lingers. The village is still a treasure trove of tradition, folk-lore, and folk-ways which can be rescued by prompt and sympathetic research.

And this closes the circle. Since 1957 Dartmouth's program of anthropological research, already focused upon the native peoples of the North, has been expanded to include this current rescue operation, thanks to a generous grant from the Spaulding-Potter Trusts. Notebook, tape recorder, and camera are capturing the spoken language, the traditional history, the folk-lore, native arts and crafts, the ancient manuscripts, and the physical likenesses of this interesting people. Eventually, Baker Library will house a collection of Abenakiana of incalculable value for the student of anthropology, linguistics, and early New England history.

Thus Dartmouth pays its debt to Saint Francis for its present salubrious location above the Connecticut River, celebrates the memory of an outstanding Indian student, and saves from oblivion a hersitage which his labors helped to preserve for this generation.

The InThe Indian village of Odanak (Saint Francis) in Quebec.

CounciCouncillor Ambrose Obomsawin, who is helping the author as a linguistic informant.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureOur Place in the Sky

November 1959 By PROF. MILLETT G. MORGAN, -

Feature

FeatureCan Chinese Civilization Survive Communism?

November 1959 By WING-TSIT CHAN -

Feature

FeatureSocial Responsibility in Painting

November 1959 By CHARLES T. MOREY, -

Feature

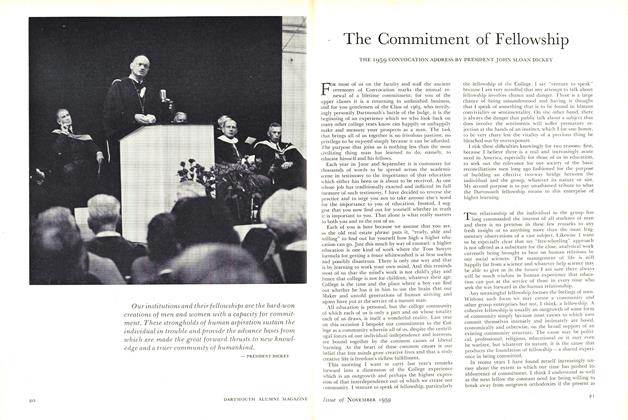

FeatureThe Commitment of Fellowship

November 1959 By PRESIDENT JOHN SLOAN DICKEY -

Feature

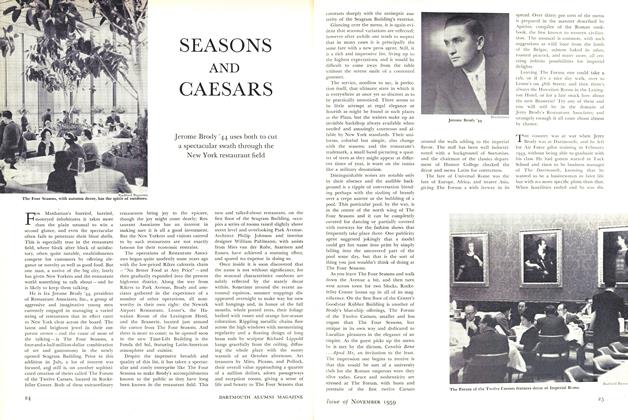

FeatureSEASONS AND CAESARS

November 1959 By JIM FISHER '54 -

Article

ArticleHow I Conquered Alcohol

November 1959 By ALAN COOKE '55

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Spot of Green at Knob Lake

March 1958 By ALAN COOKE '55 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAre Americans Saving Enough?

JANUARY 1999 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureLiberal Arts, yes 'Core of Knowledge,' no Changing the Calendar, maybe

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Mary Ross -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Overtreated American

Nov/Dec 2003 By SHANNON BROWNLEE -

FEATURE

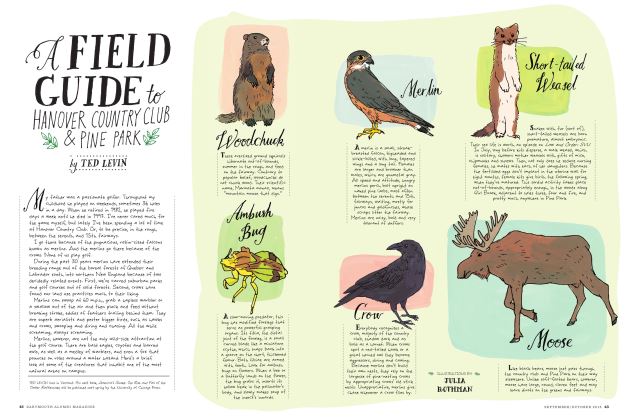

FEATUREA Field Guide to Hanover Country Club & Pine Park

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2015 By TED LEVIN -

FEATURE

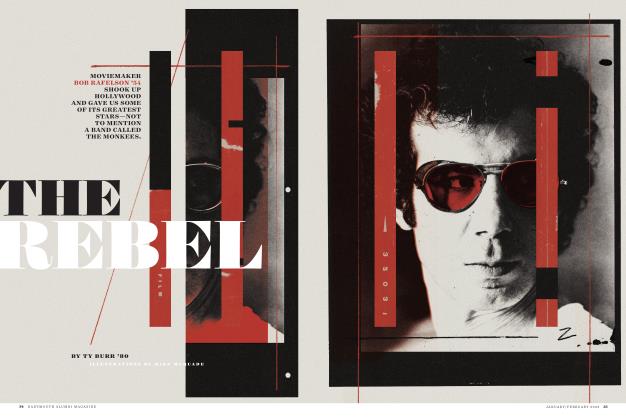

FEATUREThe Rebel

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2023 By TY BURR '80