High-quality health care, efficiently delivered and equitably available to the people who need it when and where they need it, at a cost which doesn't threaten to equate medical catastrophe with financial disaster.

A tall order. But one which MERLIN K. DUVAL '44, Assistant Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, is confident that the partnership of public and public medical resources in the United States can deliver — given sufficient ingenuity, flexibility, and commitment.

A medical educator and administrator who gained an enviable reputation for innovative programming as first Dean of the College of Medicine at the University of Arizona, Dr. DuVal approaches his role as the nation's chief health officer with a balanced blend of idealism and realism, affability and determination. He appeals to his professional colleagues' dedication to their humanitarian calling and the principles of free-enterprise medicine; he exhorts the more recalcitrant among them to put their house in order or risk throwing the baby of "America's extraordinary health capability" out with the bathwater of spiraling costs and unequal access.

Dr. DuVal dismisses the question of whether health care is a right or a privilege as outdated and simplistic. "It is a monumental folly to waste our time in rhetoric about the right of the helpless to relief from suffering in the most civilized country in the world." He urges accelerated search for workable alternatives to a potentially disastrous confrontation "between the perceived rights of an entire people and the perceived rights of an entire profession." His prescription for treating the "health-care crisis" evokes the best of both worlds: the initiative of the medical profession, retaining the freedom he sees as its greatest strength, supplemented as needed by public resources.

The government's role, Dr. DuVal asserts, is "to prod, to make selective investments to encourage institutions to find more creative approaches"; its obligation to the individual citizen is "to deploy resources to achieve a better quality of life for those who can't achieve it on their own."

Dr. DuVal uniquivocaliy predicts that by late 1973 universal health insurance — mandatory in the sense that employers must offer it — will be in effect. Like Social Security, the administration's plan depends on costs shared by employer and employee; unlike Social Security, it would be administered through private companies. For low-income families with children, not covered by employer plans, public funds would pick up part or all the check. The government would stipulate minimum benefits, regulate costs, and require that consumers have the option of participating in prepaid Health Maintenance Organizations. HMO's — group practices organized to deliver a full spectrum of health services, preventive as well as curative, to enrolled members for a set monthly fee — are an integral part of Dr. DuVal's vision of providing equal access to high-quality care at reasonable cost.

As physicians and para-medics have joined many of their lay brethren in retreat from rural and inner-city areas, maldistribution of medical personnel has aggravated an already serious national shortage. As measures toward alleviating both, Dr. DuVal points to federal stimulation of new medical schools, expanding enrollments in existing ones, and plans to increase the supply of qualified allied health manpower, a laudable example of which is Dartmouth's MEDEX program, which trains assistants "to extend the arms of the physician" by relieving him of many routine tasks. An advocate of the principle of the carrot rather than the stick, he notes such approaches as the National Health Service Corps, which assigns medical teams to underserved areas as alternative to armed-forces duty, and various financial incentives to make general practice in rural districts and city centers more attractive to young physicians.

Medical trail-blazing is an ineradicable habit with "Monte" DuVal. Imported from Oklahoma to play midwife to the embryonic Arizona medical school, first in the state, he was initially a "staff of one," involved in every facet of the pioneering venture: fund raising, building design, faculty recruitment, and curricular planning. The first class of 31 freshly minted M.D.'s emerged in May 1971, within days of his nomination to the HEW post.

Only on leave from the deanship at Arizona, Dr. DuVal looks forward to returning when his commitment to HEW is fulfilled. Seven years at the University of Oklahoma Medical Center and eight in Arizona have made confirmed devotees of the desert of Dr. and Mrs. DuVal and their three children.

Meanwhile, back at the Department, there is work to be done: programs to be promoted and support to be won. But, given the legislative tools and harmonious cooperation of public and private sectors, Dr. DuVal is confident that the health-care crisis can be on the run before he rides westward into the setting sun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBetting man's choice: Dartmouth. Then Harvard, Columbia, Cornell

October 1972 -

Feature

FeatureVerdict on the Dartmouth Institute: A-OK

October 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

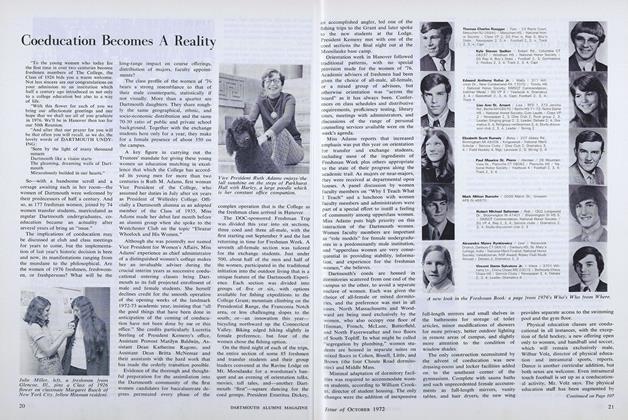

FeatureCoeducation Becomes A Reality

October 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

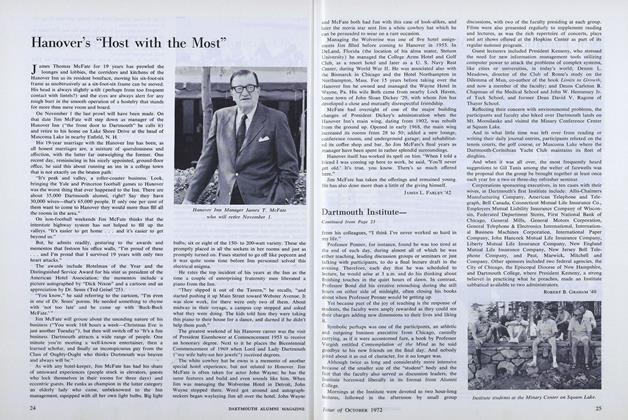

FeatureHanover's "Host with the Most"

October 1972 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

FeatureHomage to the great god Pigskin: One hundred years of Ivy rivalry

October 1972 -

Feature

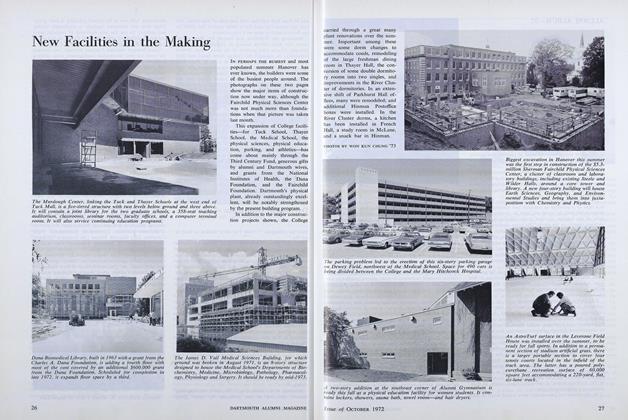

FeatureNew Facilities in the Making

October 1972

Article

-

Article

ArticleLITERARY MAGAZINE

December, 1911 -

Article

ArticleSummer Enrollment

April 1942 -

Article

ArticleThe Green Scene

JULY | AUGUST 2015 -

Article

Article1951 Adopts 2001

NOVEMBER 1999 By Casey Noga '00 -

Article

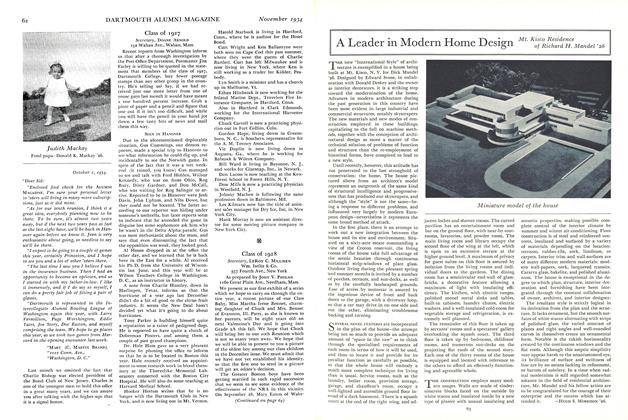

ArticleA Leader in Modern Home Design

November 1934 By of Richard H. mandel '26 -

Article

ArticleUn-Named Alumnus

May 1942 By The Editor