CHARLES T. MORRISSEY '56 is one of a new breed of historian, the man whose primary research tool is the tape recorder.

The projects he has headed in the past several years typify the varied aims of oral history. As Director of the Vermont Historical Society, he is concerned with preserving the cultural and historical heritage of what is characterized as "the most rural state in the union." At the Ford Foundation, where he is currently working on leave, he is directing the documentation of that organization's genesis and growth, its original purposes and how they have adapted.

As chief of the oral history project for the John F. Kennedy Library from 1964 to 1966, he was responsible for the most ambitious attempt yet conceived to accumulate on tape recollections of an American President and his term in office. Some 1000 persons—relatives, Congressional colleagues, political allies and opponents, members of administrative and domestic staffs of the late President—have been interviewed to provide future scholars with perhaps the most complete contemporary record ever compiled of an era in U. S. history.

A comparative old-timer in a relatively new field, Morrissey is keenly aware of the importance and urgency of oral history and as conscious of its limitations.

Oral history has grown in significance with the dwindling use of the written word in human affairs, public and private, he contends. Memoirs, diaries, and correspondence, once a major source of information for the historian, have become less common as the telephone and the airplane have simplified direct verbal communication.

The urgency is obvious, and his home state a good case in point, Morrissey believes. "Vermont is a rich pocket of American tradition, with a unique tenor of life. Its values, its life-style—the dialect itself—need to be preserved" before the older generation and its memories fade.

Oral history has proliferated rapidly since modest beginnings at Columbia University in 1948. There are 230 projects now in progress in this country, including continuing research into six presidencies and documentation of Native American tribes. Oral historians have formed a national association, of which Morrissey has been president this year; they publish a quarterly newsletter, which he edited from 1968 to 1971. And proliferation has brought problems to scale.

"Most bothersome to me about the growing interest in oral history is the fairly prevalent notion that recollections may supplant records as the primary documentation of recent history," Morrissey has written. "Records made while events were happening can still be more valuable to historians than recollections of what happened."

His approach to the Ford Foundation project exemplifies his conviction that oral history should supplement rather than supplant written records. "For twelve weeks my staff and I explored the archives of the foundation, as if we were historians with no living source to go to," he recalls. By this procedure they discovered the gaps.

Other hazards exist for the oral historian, Morrissey points out. "Probably the most familiar of all rests in the statement that some people know more than they tell and other people tell more than they know." Faulty memories can account for error; both innocent embellishment and deliberate myth-making take their toll of truth. And many are reluctant to review misjudgments—their own or others—honestly. "Candor, in the minds of some, is synonomous with imprudence," Morrissey notes.

The knowledgeable interviewer, mindful of the pitfalls, can surmount them. Of first importance is thorough familiarity with all available documents, of indispensable aid in spotting the apocryphal. Frankness about sensitive issues can be induced by confidence in the interviewer's discretion and the assurance that the subject's recollections, at his request, can be withheld from researchers for a stipulated time. A good number of interviews about the Kennedy presidency, for example, will remain sealed for varying periods.

Morrissey taught in the Great Issues course at Dartmouth during 1961-62, following graduate work at the University of California at Berkeley, where he took his master's degree. His introduction to oral history came in the pursuit of doctoral studies. He joined the National Archives in 1962, working first on the Truman project until he was "borrowed for 60 days" which became years for the JFK project.

When the Ford Foundation job is done, the Morrisseys plan to return to Vermont, where he hopes the upcoming bicentennial will add impetus—and financial support—to an accelerated accumulation of oral history, not just to record events but to preserve the tone of a culture that time is swiftly erasing.

Committed to its values, cognizant of its limitations, Morrissey is convinced that oral history can add significantly to filling in the tapestry of recent American life.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFour Views of Educational Opportunity at Convocation Opening the 203rd Year

November 1972 -

Feature

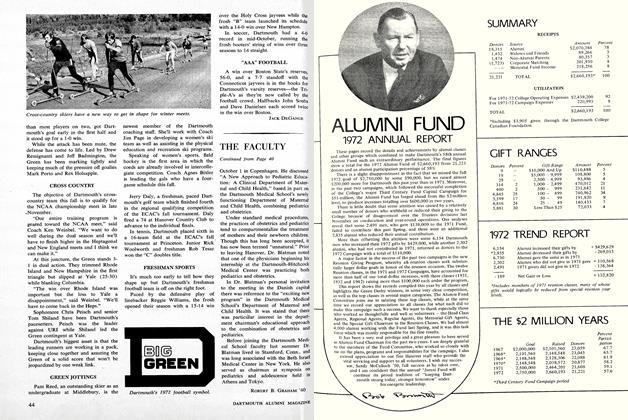

Feature1972 ANNUAL REPORT

November 1972 -

Feature

FeatureElection '72: A Historian's View

November 1972 By JAMES E. WRIGHT -

Feature

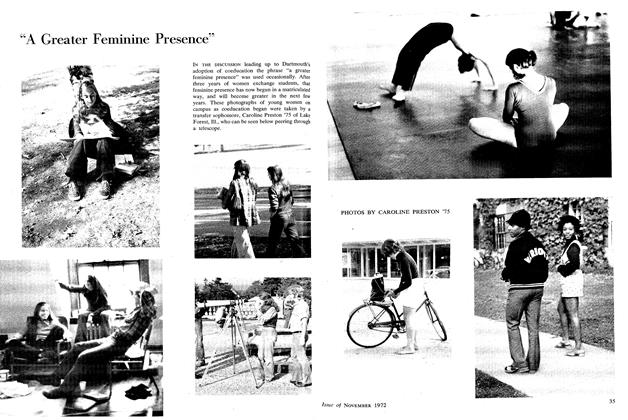

Feature"A Greater Feminine Presence"

November 1972 -

Article

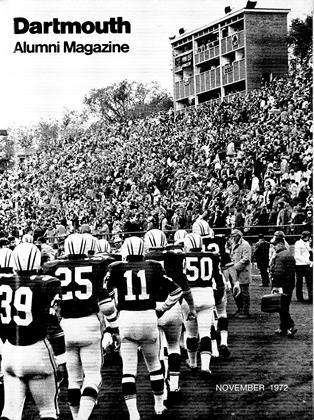

ArticleBig Green Teams

November 1972 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

November 1972