It is in the long-run national interest of the United States to live besidea Canada that is independent politically, economically, and culturally

PRESIDENT OF THE COLLEGE, EMERITUS,BICENTENNIAL PROFESSOR OF PUBLIC AFFAIRS

Little noted in this country but of great significance to Canadians was a pronouncement made by President Nixon when Prime Minister Pierre Elliot Trudeau visited the White House in December 1971. Upon returning to Ottawa, the Prime Minister reported to Parliament as follows:

One of the purposes of my visit was to seek reassurance from the President, and it can only come from him, that it is neither the intention nor the desire of the United States that the economy of Canada become so dependent upon the United States in terms of a deficit trading pattern that Canadians will inevitably lose independence of economic decisions. . . . He assured me that it was in the clear interests of the United States to have a Canadian neighbour, not only independent both politically and economically but also one which was confident that the decisions and policies in each of these sectors would be taken by Canadians in their own interests, in defence of their own values, and in pursuit of their own goals. . . . We are a distinct country, we are a distinct people, and our remaining such is, I was assured, in the interests of the United States and is a fundamental tenet of the foreign policies of that country as expressed by the Nixon administration.

Trudeau, leaving nothing to chance, characterized the President's words as "fantastic," in the happiest sense of the word, of course. And clearly it was this reception of his December reassurances that led President Nixon to elaborate on the same theme when he addressed the Canadian Parliament in April 1972. However taken-for-granted the President's words may be for Americans, they are in fact addressed to the most fundamental issue in the contemporary relations of the two countries and it is not unlikely that they will prove quite as long-lived as they are unprecedented. No previous presidential utterance has ever proclaimed the independence of Canada in its relations with the UnitedStates as being "in the clear interests of the United States."

Canadian independence in other respects has had a long history of entanglement with the American national interest. Indeed, American interest in promoting Canada's independence predated the United States as a nation. Washington, Franklin, Lafayette and the other notables of the American Revolution at various times sought unsuccessfully, through both persuasion and force, to further the rebellion against the British Crown by getting the Canadians to join their cause.

The decisive failure of the American effort to "liberate" Canada from British rule by military force, of course, came in the War of 1812. One can only speculate on what later form the issue of Canadian independence would have taken if these early American incursions had succeeded, but it is probably safe to say that the issue of an independent Canada would not have disappeared; almost certainly it would have resurfaced as an earlier, more militant call for a QuébecLibre.

The American national interest in the independence of Western Hemisphere nations as expressed in the Monroe Doctrine was more implicit than explicit in respect to Canada prior to the rise of the Axis Powers. From World War II on through the cold war and the advent of intercontinental bombers and missiles, this Monroe Doctrine form of American national interest in Canadian independence was readily translated into a concern for the protection of Canada as a necessary condition of American military defense. At the time, this perception of the external threat was shared by both Canada and the United States and the joint continental defense arrangements which resulted were all but universally welcomed in both countries. During this period the rhetoric of "partnership" and the concept of "continentalism" spread into other areas of the relationship. This era reached its full flowering with the Merchant- Heeney Report of 1965 under the rubric of "Principles for Partnership."

Today, the words "partnership," "continentalism" and "integration" as well as the concept behind them are eschewed by most Canadians and bitterly rejected by some.

II

The validity of the cliché that Americans take Canada for granted is borne out by the unexamined ease with which in little more than 100 years we have switched from an assumption that Canada's "manifest destiny" was to be annexed by the United States to today's benign unawareness that Canada has anything to worry about from us. It is only one of our areas of ignorance about things Canadian, but it is a fact that until very recently it has not occurred to more than a handful of publicists, scholars and diplomatists that a well-intentioned United States with its spreading American presence in Canadian life might be regarded as, let alone actually be, a threat to a viable Canadian nationhood.

Greater awareness of this particular insensitivity could be immensely instructive to American understanding—in bringing to the surface two ill-founded premises which underlie American assumptions about the U.S.-Canadian relationship, namely: our intentions being good, no harm can result; and the two countries being so similar, what is true for the United States is also true for Canada.

As far as U.S. intentions are concerned, there is very little concern in Canada that contemporary America has ulterior designs on Canadian independence. Even the most militant Canadian nationalists do not make this charge; their grievance rather is that the omnipresent American influence in all its manifestations of defense, trade, investment, publications, mass media, academic life and popular culture just keeps on spreading with no thought on the part of Americans and too little on the part of Canadians for what, in the view of the nationalists, must be devastating consequences to Canadian nationhood. It is not within the purview of this article to analyze the nature and impact of today's American presence in Canada, but it must be said unequivocally that for both better and worse it is an awesome reality. If Americans have a genuine interest in the future quality of Canadian nationhood they, as well as Canadians, must reckon with this reality.

Our taken-for-granted good intentions toward Canada have beyond question dulled our sensitivity to the increasingly critical perception on the part of many Canadians of the consequences of American influences in their national life. And perhaps more pernicious is the American tendency to assume that because there are many similarities and shared experiences between them, the two nations are essentially alike in all fundamental things. There is probably no firmer tenet of faith in the Canadian character than that this is not so. And there are few situations that are better proof of the validity of this Canadian belief than the fundamentally different posture on the issue of national independence in the two societies. For over 150 years, Americans have been able to take independent nationhood for granted. It therefore comes naturally to us, particularly when we are desensitized by our good intentions, to assume that Canada, being, as it seems to us, so like us and so similarly situated, also takes her nationhood for granted. The hard fact is that she never has, she does not now, and for the foreseeable future will not be able to take independent nationhood for granted in any sense similar to that of the United States.

The division of views that exists in Canada today about the American presence is not over whether or not it is a major factor in Canadian life but rather over how serious it is as a threat and how it should be met. The main disagreement is whether some of the proposed remedies, particularly in the control of foreign investment, would not be more harmful to Canada and individual Canadians than an often irksome, ubiquitous American presence. This is particularly true on the heated issue of American investments in Canada. The recent proposal of the Trudeau government for screening foreign "takeovers" to serve Canadian purposes may or may not dampen the issue for a time, but it will not satisfy the militant nationalists and its implementation inevitably will add another contentious issue to the already overburdened agenda of Ottawa-Provincial relations. At the same time the proposal should appeal to the substantial sectors of Canadian opinion that, while not prepared to cede the nation to the Americans as their hypernationalistic critics claim, believe the American presence is probably as inevitable as it may be irksome, and that Canadian well-being will be better served by learning to absorb it and put it to Canadian ends rather than by expending energy and sacrifice on what they regard as an ultimately frustrating, if not actually anachronistic, effort to exorcise it from Canadian life.

One could analyze the differences in perceptions of the threat of the American presence regionally, economically, vocationally, politically and ethnically, without altering the essential conclusion that there is in Canada today a substantial, spreading concern which is not likely to be well met by leaving it to time and unattended circumstances. Presumably it was such a judgment of the matter that led Prime Minister Trudeau to seek and President Nixon to give explicit assurances that the United States has a stake in the political, economic and cultural independence of Canada.

III

Viewed positively and functionally, the stake of contemporary America in an independent Canada is grounded not in Canada but in the United States. It is in the self-interest of this country as a great concentration of power to be subject to an independent, critical scrutiny, which is free of both the hostility of an adversary and the acquiescence of a sycophant, as well as sufficiently knowledgeable to be received seriously, even if not always accepted.

One of the tenets of American society is that its pluralism, its constitutional freedoms and its democratic process assure the nation of a measure of self-criticism sufficient to protect its policies from unexposed error. The historical record generally supports the proposition that the nation's errors have rarely for long flourished simply for want of exposure, but the time lag between "a voice crying in the wilderness" and the straightening of the path has sometimes in the past been rather long.

The nation's experience with the Vietnam War testifies convincingly that U.S. self-criticism is far from being a paper tiger, but equally importantly, the Vietnam War experience leaves little room for future argument about the high degree of interaction in a communication-intensive world between a nation's self-criticism and that coming from the outside. American critics of the war might have prevailed on their own; we cannot be sure about this, but we do know that criticism from the outside constantly played a confirming, fortifying role and was a sufficiently worrisome factor to bother American officialdom. Although Canadian public criticism of the war was slow to gather and has been mostly moderate, it has been sufficiently widespread and sustained to register here, and on the one occasion when Lester Pearson, then Canadian Prime Minister, ventured to expose his views to the American public on the desirability of a pause in the bombing, President Johnson was—to use a Texas-sized understatement—not amused.

China policy is one of the clearest examples both of the value to the United States of an independent Canada and also of the degree to which Canadian fear of U. S. resenment of Canadian policy divergence can stifle Canadian independence. As early as 1950, under the leadership of Prime Minister St. Laurent and Lester Pearson, then Minister of External Affairs, Canada was disposed to follow the lead of Britain and India in extending recognition to Peking. She held off, however, and the decision itself was delayed for another 20 years, largely because, as St. Laurent's biographer, Dale Thomson, states, "the possible advantages were outweighed by the disadvantages within Canada and in relations with her neighbor." Mr. Pearson has never made a secret of his judgment that the matter had not seemed worth "a first- rate row with Washington." At the same time the Canadian government's divergence of view on the matter was no secret to Washington and over the years the possibility of eventual recognition was freely discussed in the Canadian press and public circles, as well as the academic community, all very much in contrast to the situation in the United States where serious discussion of the subject was immobilized in a bipartisan freeze that loosened a little in the early sixties but then hardened again as the American situation in Vietnam worsened.

We do not as yet have the full story behind either the Canadian recognition of Peking in 1970 or the ensuing pingpong charade which preceded the U.S.-Chinese rapprochement in 1971, but unless there are later revelations that totally discredit what is now known and presumed, it seems certain that the independent Canadian initiative was one of the significantly "favorable circumstances" that helped both the American public and U.S. officialdom to break out of the dangerous, mutually reinforcing immobility that for 20 years characterized the U.S.-Chinese standoff. In this matter as in few others, the osmosis of the border worked a transfer of influence from north to south.

China policy also provides a classic example of the degree to which the U. S. national interest in an independent Canada can be compromised by a Canada which, rightly or wrongly, lacks confidence in its capacity to pursue a divergent course from the United States without undue risk, as the diplomats are fond of saying, of inducing a "counterproductive" U.S. reaction. The attitudes of the American Congress and press toward an independent Canada are particularly important. Wisely or not, Canada gives special weight to congressional sentiment as the best single indicator of both the direction and intensity of American national feelings. John W. Holmes, a former officer of the Department of External Affairs and an astute student of the U.S. relationship, has said of the early decision not to recognize Peking: "Direct pressure from Washington was not so much a factor as Canadian uneasiness about provoking the wrath of the U.S. Congress."

Although American observers have given Canada considerable credit for leading the way on the recognition of China, Prime Minister Trudeau understandably refrains from claiming any intention to lead the United States out of the wilderness. In a December 1971 interview with James Reston of The New York Times, however, the Prime Minister spelled out his belief in the value of Canadian initiatives, saying that: ". . . because we're a smaller and more manageable society ... I think we can afford to take some risks of opening up new avenues which we think are correct. For even if they are incorrect we will be slapped down by events or force of circumstances or by our friends without great adverse consequences on peace and stability in the world. But for a power like yourselves, if you are naïve and your confidence doesn't breed confidence, but rather brings a terrible response from other countries, then it is of much greater moment not only for you but for the whole world, than if we make a mistake."

Whether or not the servant girl's justification of her indiscretion—". . . but, ma'm, it's such a little baby"—has as much to be said for it in international affairs as Prime Minister Trudeau suggests, there can be little doubt that divergent Canadian initiatives can on occasion provide the United States with a sort of vicarious experience against which to make a more confident judgment of its alternatives.

Parenthetically, but not unimportantly, it should be noted that the U.S. stake in the vicarious experiences of Canadian policy divergences may be fully as great in domestic affairs as in foreign policy. The federal structures of the two countries have a particularly fruitful mix of contrast and similarity for purposes of comparison. A notable current instance is found in a 1971 study of the U.S. Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations entitled "In Search of Balance—Canada's Intergovernmental Experience." This report, as described by the Commission Chairman, Robert E. Merriam, "focuses its attention on a comparative analysis of Canadian experience relating to selected intergovernmental fiscal tensions prevalent in the United States. . . . The Commission's concern centers on an analysis and description of Federal-Provincial relations, financing of public education and social welfare, and Provincial-local relations."

As the United States moves toward radically new fiscal relationships between the federal government and the states and of both to local communities, the more venturesome and varied experience in Canada with these relationships, particularly with revenue-sharing arrangements, may be useful to Americans. A Canadian political scientist, Pauline Jewett, with first-hand experience as a member of Parliament, has described Canada as a U.S. "window" for observing social experiments and "as a kind of loyal opposition to traditional conservatism in the United States." Canadians take a special pride in their particular brand of government as a combination of some of the better features of both the British and the American systems. A growing interest on the part of Americans in the social policies of an independent Canada will serve a significant U.S. national interest and could contribute significantly to the long-range health of the relationship.

IV

A second area of international concern sufficiently basic to be a national interest of the United States is that Canada should be accepted in the eyes of other nations as a genuinely independent nation. For a considerable period of the post-World War II era, especially during the deepest freeze of the cold war, there was a widely held view in the international community that Canada was peculiarly well suited to play what has been called a "mediatory role in world affairs." "Middle powermanship," with its accommodating, imprecise view of what "middle" meant, became in the eyes of many Canadians a way of being on the side of the angels while still remaining in geopolitical realities a North American nation. And as things then stood, most other nations, including the United States, welcomed the existence of such a Canada. However the Canadian middle- power role was perceived at home or by others, it assumed a Canada that, while fundamentally friendly to the point of alliance with the United States, could still be regarded by the other side as sufficiently independent not to be classed as a spear-bearer for "American imperialism."

This benign ambivalence was put to good use by a generation of remarkable diplomatists, led by Lester Pearson, in rendering distinctive service to the international community through such major undertakings as the resolution of the Suez crisis in 1956, the U. N. Emergency Force in the Middle East, the U. N. operations in the Congo, U. N. peacekeeping in Cyprus, and as a member of the largely frustrated tripartite Commission for Supervision and Control in Indochina. From 1945 through 1970, Canada actually participated in ten U.N. peacekeeping operations.

In 1968, with the coming to power of the Trudeau government, Canada undertook a comprehensive reappraisal of the national interests and principles which should guide her foreign policies in a changing world where, as the 1970 white paper, "Foreign Policy for Canadians," put it: "International institutions which had been the focus and instrument of much of Canada's policy were troubled . . ." and where "the world powers could no longer be grouped in clearly identifiable ideological camps...." A combination of considerations, some internal, such as the mounting crisis in French Canada, and others external, led the Trudeau government explicity, if perhaps gratuitously, to reject the type-casting of Canada "as the 'helpful fixer' in international affairs."

Even assuming that Canada's "middle-power" heyday as interpreter, mediator and peacekeeper for the international community is a thing of the past, there certainly will be future needs for such a nation to serve what might be fairly designated the disinterested interests of peace. When such circumstances arise, a Canada that has practiced, as the 1970 white paper adjures, an unrelenting cultivation of her national interest in remaining "secure as an independent political entity" can hardly fail to be a source of strength in the international community and as such a substantial national interest of the United States.

While most policy problems in the relationship can be met within a relatively short time-frame, the U. S. stake in having Canada regarded by other countries as genuinely independent of the United States requires a substantial showing of sustained U.S. sensitivity. Such convictions must be grown in a variety of situations over a period of time; they cannot spring "fully armed" from the brows, or public statements, of either presidents or prime ministers at a moment of need.

Finally and most fundamentally, all other considerations of U.S. national interest, now and in the future evolution of the relationship, depend upon the relationship's psychological health. As things stand today, the sine qua non of such health is that Canadian independence should pass current with Canadians themselves. It was therefore no idle thing that the Prime Minister chose to feature the President's commitment to "a Canadian neighbor . . . which was confident" of its independence of choice and decision. Actually such Canadian confidence is still and for the foreseeable future is likely to be an uncertain thing that both requires and generates a new-nation kind of highly self- conscious nationalism. The concern which Americans can share with most Canadians is that what is still an essentially positive nationalism should not deteriorate into a frustrated, debilitating, neurotic preoccupation with the United States as the cause of all that's wrong and uncertain in Canada.

V

The interest of the United States in an independent Canada must reckon with the fact that there will always be divergences of interest and view between the two nations. Even though some issues may arouse strong feelings, where the United States thinks it has the better case it assuredly will seek to prevail. An independent Canada neither needs nor should expect to meet a soft, complaisant United States on the other side of such arguments. In truth, U.S. paternalism in the dealings of the two countries could quickly give Canadian independence the coup de grâce. The point was made by A. E. Ritchie, Undersecretary of State for External Affairs, before a committee of the Canadian Parliament on May 5, 1970, in testifying that in U.S.- Canadian negotiations the expectation of favors was unrealistic and that their acceptance by Canada would be "risking our independence in a way that I think we do not risk it when we negotiate a pretty hard-headed bargain on a particular point."

Realistically viewed, the issue here is not one of favors, paternalism, soft negotiations, suppression of dissatisfactions and a fantasy of bland politeness between the two societies; rather, it is the ability of the United States in its enlightened self-interest to live and work and disagree, without petulance or retaliatory posturing, with a Canada which on occasion, for reasons of her own, chooses to diverge from the United States in the conduct of her foreign affairs and which for a long time to come will be an uneasy neighbor. The important truth for both nations to perceive and practice is that this is one of those twilight areas of statecraft where great consequences may turn on differences of degree: for Canada, in the way she distinguishes between the legitimate assertion of American interests and the remote possibility of being blackguarded to her serious harm for a divergent initiative; for the United States, in its need to assert its views and interests without losing sight of its national interest in having a neighbor which is neither pusillanimous nor paranoid.

Canadian divergences from American policy on China recognition and the vote on U.N. admission and in such matters as wheat transactions with China, trade with Castro's Cuba, NATO force reductions, assertions of jurisdiction in coastal and Arctic seas, prime ministerial observations in Moscow about life alongside the United States, the Amchitka nuclear tests, etc.—all these fall into a perspective that from our point of view is at worst undesirable rather than unbearable. At best they protect the larger, long-run national interest of the United States in a Canada which is accepted both at home and abroad as a genuinely independent nation and which as such may have much to offer to the United States and to the evolving relationship of the two countries.

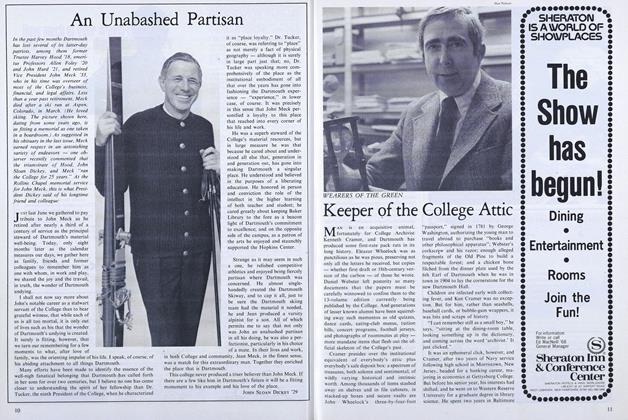

Professor John Sloan Dickey photographed in his Baker Library office.

MR. DICKEY'S ARTICLE is a condensed and slightly revised version of a paper, "Canada Independent," written as part of his studies as Senior Fellow of the Council on Foreign Relations and first printed in the July 1972 issue of Foreign Affairs. It is one chapter of a larger project dealing with the impact of the American presence in various forms on Canadian nationhood and the stake of the United States in an independent Canada.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureEgyptologist

December 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureHall of Hallmark

December 1972 -

Feature

FeatureClub Officers Hold Annual Meeting

December 1972 -

Feature

FeatureRugby Posts A Winning Fall Season

December 1972 By TREVOR O'NEILL '73 -

Article

ArticleFaculty

December 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Article

ArticleBig Green Teams

December 1972 By Jack DeGange

JOHN SLOAN DICKEY '29

Features

-

Feature

FeatureThe Faculty

April 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Rise of Research

FEBRUARY 1989 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureTHE OLD ROMAN SPEAKS TO US STILL

June 1976 By DAVID SHRIBMAN -

Feature

FeatureWhat Is Success?

MARCH 1983 By E. R. (Skip) Sturman '70 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryM. Lee Pelton

OCTOBER 1997 By Jane Hodges '92 -

Feature

FeatureHeeding the Beat of a Different Drummer

SEPTEMBER 1987 By Teri Allbright