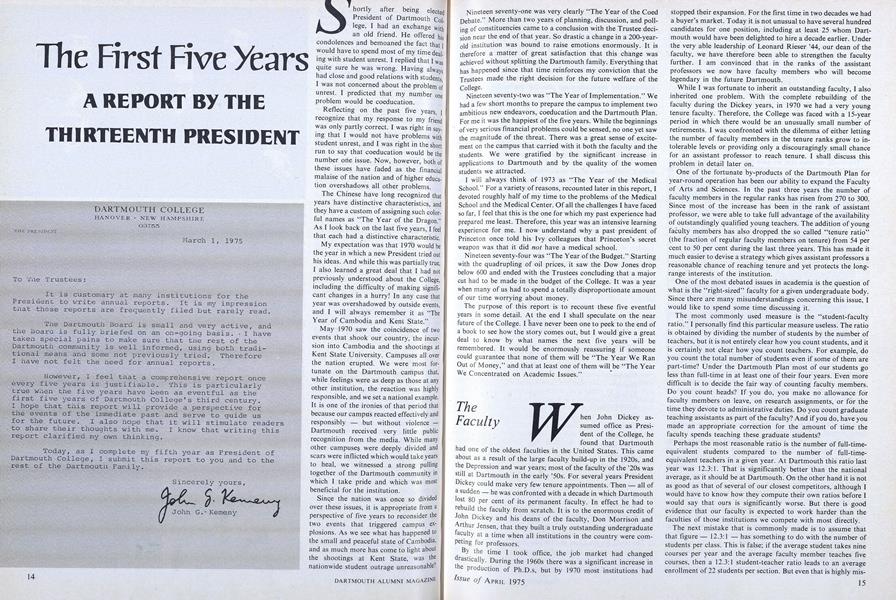

When John Dickey assumed office as President of the College, he found that Dartmouth had one of the oldest faculties in the United States. This came about as a result of the large faculty build-up in the 19205, and the Depression and war years; most of the faculty of the '20s was still at Dartmouth in the early. For several years President Dickey could make very few tenure appointments. Then - all of a sudden - he was confronted with a decade in which Dartmouth lost 80 per cent of its permanent faculty. In effect he had to rebuild the faculty from scratch. It is to the enormous credit of John Dickey and his deans of the faculty, Don Morrison and Arthur Jensen, that they built a truly outstanding undergraduate acuity at a time when all institutions in the country were competing for professors.

By the time I took office, the job market had changed During the 1960s there was a significant increase in the production of Ph.D. s, but by 1970 most institutions had stopped their expansion. For the first time in two decades we had a buyer's market. Today it is not unusual to have several hundred candidates for one position, including at least 25 whom Dartmouth would have been delighted to hire a decade earlier. Under the very able leadership of Leonard Rieser '44, our dean of the faculty, we have therefore been able to strengthen the faculty further. I am convinced that in the ranks of the assistant professors we now have faculty members who will become legendary in the future Dartmouth.

While I was fortunate to inherit an outstanding faculty, I also inherited one problem. With the complete rebuilding of the faculty during the Dickey years, in 1970 we had a very young tenure faculty. Therefore, the College was faced with a 15-year period in which there would be an unusually small number of retirements. I was confronted with the dilemma of either letting the number of faculty members in the tenure ranks grow to intolerable levels or providing only a discouragingly small chance for an assistant professor to reach tenure. I shall discuss this problem in detail later on.

One of the fortunate by-products of the Dartmouth Plan for year-round operation has been our ability'to expand the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. In the past three years the number of faculty members in the regular ranks has risen from 270 to 300. Since most of the increase has been in the rank of assistant professor, we were able to take full advantage of the availability of outstandingly qualified young teachers. The addition of young faculty members has also dropped the so called "tenure ratio" (the fraction of regular faculty members on tenure) from 54 per cent to 50 per cent during the last three years. This has made it much easier to devise a strategy which gives assistant professors a reasonable chance of reaching tenure and yet protects the longrange interests of the institution.

One of the most debated issues in academia is the question of what is the "right-sized" faculty for a given undergraduate body. Since there are many misunderstandings concerning this issue, I would like to spend some time discussing it.

The most commonly used measure is the "student-faculty ratio." I personally find this particular measure useless. The ratio is obtained by dividing the number of students by the number of teachers, but it is not entirely clear how you count students, and it is certainly not clear how you count teachers. For example, do you count the total number of students even if some of them are part-time? Under the Dartmouth Plan most of our students go less than full-time in at least one of their four years. Even more difficult is to decide the fair way of counting faculty members. Do you count heads? If you do, you make no allowance for faculty members on leave, on research assignments, or for the time they devote to administrative duties. Do you count graduate teaching assistants as part of the faculty? And if you do, have you made an appropriate correction for the amount of time the faculty spends teaching these graduate students?

Perhaps the most reasonable ratio is the number of full-time-equivalent students compared to the number of full-time-equivalent teachers in a given year. At Dartmouth this ratio last year was 12.3:1. That is significantly better than the national average, as it should be at Dartmouth. On the other hand it is not as good as that of several of our closest competitors, although I would have to know how they compute their own ratios before I would say that ours is significantly worse. But there is good evidence that our faculty is expected to work harder than the faculties of those institutions we compete with most directly.

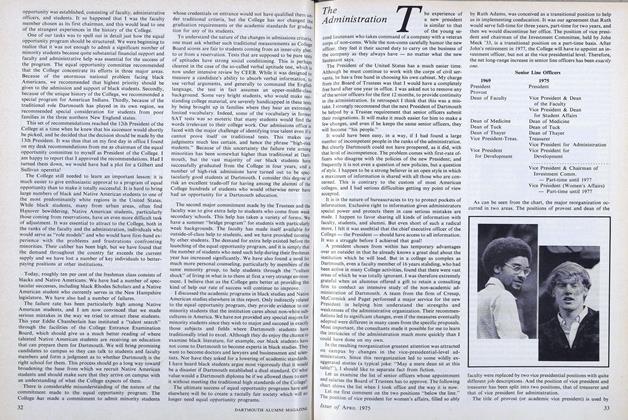

The next mistake that is commonly made is to assume that that figure - 12.3:1 - has something to do with the number of students per class. This is false; if the average student takes nine courses per year and the average faculty member teaches five courses, then a 12.3:1 student-teacher ratio leads to an average enrollment of 22 students per section. But even that is highly misleading, since practically no courses are average courses. If one looks at the Dartmouth catalog, it appears that the ma- jority of courses (and sections of courses) are either seminars or very small sections. I would like to explain why this is a mis- leading impression. To do this I will use an over-simplified model of how course enrollments look to different constituencies. Let us suppose that the following represents a typical distribution.

Enrollment ModelType of Average Number of FacultySection Enrollment Sections Enrollments Load Lecture 120 1 120 2 Regular 30 8 240 8 Seminar or 12 10 120 10 small Total 25 19 480 20

The model assumes that we have only three kinds of courses: lecture sections with 120 students, regular sections with 30 students each, and seminars or small course sections with 12 students each. The next column in the table shows how 19 sections might be distributed among the three types, indicating that the majority of sections are small.

How would this distribution look to the faculty? In the final column I have counted the lecture section as a double load such sections are often taught by more than one person. Note that the average faculty member will spend only ten per cent of his time (2 of 20 sections) in lecture courses and half his time (10 of 20) in seminars or small sections. Thus the distribution is extremely attractive from the faculty's point of view and might lead critics to ask whether we are offering too rich a mix. However, the column labeled "Enrollments" shows that the situation looks quite different from the student's point of view. The average student spends only one-quarter of his time in seminars or small sections and spends an equal amount of time in large lecture courses. I certainly feel that this is not too rich a mix, and any major shift would weaken the quality of the Dartmouth education.

I feel quite differently about courses that enroll three, four, or five students. I am sure that some faculty members think that they are helping students by giving such almost individualized instruction. However, the overall impact on the College is negative. Suppose that the 19 sections above included four very small courses averaging four students. To keep the faculty load constant, we would have to reduce the number of seminars (and reasonable-sized small courses) from ten to four, and increase the number of regular courses from eight to ten. The net effect is that while 16 students would get a superb educational experience, only a total of 64 students would be in small sections. The average student would spend only 13 per cent of his or her time in small sections, instead of 25 per cent.

Therefore, very small courses are justified only under exceptional circumstances. There are occasions when a department that has a small number of majors must offer specialized courses even to a very small enrollment. But such courses should be offered in alternate years and only if absolutely necessary. Dean Rieser is convinced that we have a surplus of such courses, and he is currently undertaking a systematic review with the expectation that some of them can be eliminated.

An important issue to consider is whether, given the increase in our enrollment, adding 30 members to the Faculty of Arts and Sciences was an adequate response. At first look we note that while the undergraduate body increased from 3,250 to 4,000, or by 23 per cent, the faculty increased by only 11 per cent. However, one must remember that at the time we switched to the Dartmouth Plan, the faculty reduced the graduation requirement from 36 courses to 33. In addition there are some economies in size; a course that previously had an enrollment of seven students and now has an enrollment of nine does not require additional faculty manpower. Therefore, as far as course enrollments are concerned, the increase seems just about right.

But there are a number of complicating factors. First, any radical change requires a period of adjustment. The effort to determine which courses should be given in each of the four terms and how to distribute faculty members - each of whom teaches only three terms - among the four terms, has involved lengthy discussion and much long-range planning. The matter was further complicated during the transition years by the fact that a portion of our undergraduate body was still under the traditional plan There is no doubt that this has imposed a significant extra load on the faculty, but I hope that most of the transitional difficulties are behind us.

A second important consideration is the fact that while course enrollments have gone up much less than the increase in the student body, the number of majors has increased by the full 23 per cent of additional students. And majors represent an extra burden for academic departments whether or not the students are on campus. So do the increased number of off-campus programs. I would conclude that we have not allowed sufficiently for this additional demand on the time of the faculty. Unfortunately, given our severe budgetary problems, I do not see any chance of increasing the size of the faculty at this time.

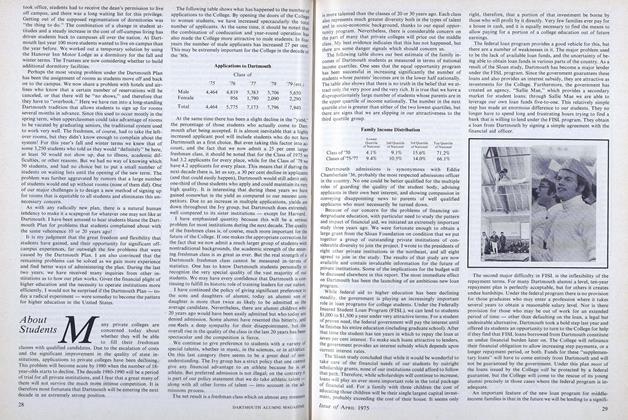

The transition has been made even more difficult by large shifts in student enrollments and the election of majors. The problem is illustrated by showing what has happened to the number of majors in various departments; similar remarks could be made about course enrollments. The following table shows the average number of majors in the larger departments for the last six classes that entered Dartmouth before I took office as compared with the Class of 1976, which was the first coeducational class admitted to Dartmouth.

Distribution of MajorsA verage Class ofMajor Classes '68-'73 '76 Anthropology 14 17 Art 23 39 Biology 47 102 Chemistry 20 36 Drama 7 20 Economics 63 106 Engineering 31 32 English 102 88 Geography 25 17 Geology 17 23 Government 90 83 History 73 83 Mathematics 42 66 Philosophy 16 29 Physics 11 24 Psychology 78 61 Religion ' 14 15 Romance Languages 21 31 Sociology 22 17

The totals for the Class of 1976 are about 20 per cent higher than for the average of six earlier classes because the Class of 1976 was the first large class; later classes are even larger and have a larger percentage of women in them.

Comparing the two columns of figures one notes that some dramatic shifts in student interests have occurred. But the fact that the Class of '76 has women students in it does not explain the dramatic changes in the table; some sex differences do appear, but they are second-order effects. The changes are caused primarily by three factors: (1) students are much more worried about getting a job and tend to elect majors that they think will be useful in finding a job; (2) there has been an amazing increase nationally in the number of students who enroll in a pre-medical curriculum; (3) Hopkins Center has had a major effect on Dartmouth College.

It is interesting to examine the table above in terms of our three academic divisions. The social sciences have traditionally attracted about half of the students at Dartmouth. For the Class of '76 the social sciences still provide the largest number of majors, but there has been a significant shift in their position relative to the other divisions. And there have been dramatic changes within the social sciences, with economics showing a spectacular resurgence and several other departments experiencing decreases.

Traditionally, the second largest number of majors at Dartmouth has been in the humanities. We note that the English Department is no longer the most popular department for majors. However, the losses in English have been more than made up by significant increases in drama, art, and philosophy. This division has roughly "held its own."

The truly spectacular increase has come in the sciences, led by the Biology Department, and today science majors outnumber humanities majors at Dartmouth. There has also been a large increase in the enrollments in science courses.

Dean Rieser and his colleagues have had the responsibility of estimating how the 30 new faculty members should be distributed among the three divisions. I believe that they have done an excellent job, but they could not have foreseen such dramatic changes in student interests. In retrospect we know that a number of departments have received an increase in faculty not justified by student enrollments, while other departments are now shorthanded. It is natural for the latter departments to feel that they have been "cheated by the Dartmouth Plan." The deans face a significant challenge to achieve a more equitable distribution of faculty.

No one enters academic life in the hope of getting rich, but any institution that desires to attract and retain a first-rate faculty must provide competitive salaries. Twenty years ago academic salaries were scandalously low. And Dartmouth's salaries were low compared to other schools. For example, I came to Dartmouth mouthin 1953, as a full professor, at a salary of $6,000. Fortunately, it was also the beginning of a relatively affluent period for academic institutions, and there was a prolonged period during which faculty salaries rose significantly.

John Dickey was faced with the challenge not only of keeping up with national increases but of trying to close the gap between Dartmouth's salaries and those of our close competitors. Although it took 20 years, the objective was achieved. Two years ago we felt that we had finally reached a level where our salaries were competitive with those of our sister institutions. Today the average Dartmouth full professor has a salary of 523,000; even taking inflation into account, that is a vast improvement. (And yet academic salaries are much lower than those typically earned by doctors or lawyers or businessmen.)

Just at the time when we could feel relatively happy about the financial well-being of the faculty, colleges were hit by runaway inflation and terrible financial problems. Faculty salaries cannot keep up with double-digit inflation. We can only hope that the country will work its way out of the present malaise quickly, so that there will not be a major deterioration in the economic status of the faculty.

I have heard it argued that Dartmouth College can afford to pay lower salaries because of the attractions of living in or near Hanover. True, our location is a tremendous advantage in attracting teachers, and it accounts in part for the fact that we lose so very few senior faculty members. And if professors' salaries were competitive with other professions, I would not hesitate to say that our salary level should be 10 to 20 per cent lower than for schools in unattractive locations. But when one recognizes that the average assistant professor, who after completing college spent five to six years obtaining a Ph.D. and has been on our faculty for three years, earns only $13,300, the argument loses its force. We are not concerned if state or city institutions in unattractive locations pay a significant premium over our salaries. But when we are competing with other Ivy institutions, or with outstanding small liberal arts colleges, we must recognize that young faculty members can barely support their families and that they cannot afford to trade a lower salary for the attractions of Dartmouth.

Not only did salaries improve spectacularly during the Dickey administration, but there was also a significant improvement in the College's retirement plan. Many professors who retired ten or more years ago have found themselves in difficult financial straits in the past few years. The percentage contributed to the retirement plan was too low and was based on a salary that would represent a poverty level at today's prices. The Trustees have twice taken action to help out retired faculty members and officers of the College. The most recent action occurred last fall, and we are about to announce supplementary benefits for those retired officers of the College who have unreasonably low incomes.

We hope that in the future such supplementary help will not be necessary. For a number of years the College has contributed an amount equal to 16 per cent of a professor's salary to an annuity fund (TIAA-CREF) after age 40, with smaller contributions in earlier years. Those faculty members who will have been under this plan for most of their academic careers should be able to achieve a reasonable retirement income, barring run-away inflation! As a matter of fact, we are currently facing a different dilemma. Our plan was designed at a time when Social Security played a relatively modest role in the retirement of middleincome people. Given the recent vast escalation of both Social Security payments and benefits, the Trustees have concluded that we must integrate our retirement program with Social Security. This will not be easy to achieve, since it is very difficult to predict what the effect will be of Social Security legislation. It would help enormously if Congress would guarantee certain minimum benefits based on total earnings.

Dartmouth has made a number of other improvements in fringe benefits such as major medical, disability, and life insurance, which at relatively modest cost insure the faculty against financial disaster.

I once heard John Dickey quote the saying, "Changing a college curriculum is like moving a cemetery." I know just what he meant. While in some sense the curriculum is always in flux departments continue to review their course offerings, old courses are dropped and new ones are substituted - the change nevertheless is very slow. Over a period of several decades a complete revision may occur, but over a period of five years the change is hardly noticeable.

During the past five years, the greatest change has occurred in interdisciplinary programs. We currently have such programs in environmental studies, comparative literature, urban and regional studies, black studies, Native American studies, mathematics and the social sciences, and the recently created program in Asian studies. Programs introduce subject matter that does not fall within the province of a single department.

Last year the faculty regularized the rules governing interdisciplinary studies. These programs are originally approved for a period of three years, at the end of which they are subject to'a rigorous review. If they pass this review, a more permanent status is given for the next five years. During the second stage, programs are permitted to make tenure appointments in conjunction with existing departments. For example, the distinguished chairmen of environmental studies and black studies hold, respectively, tenure appointments in earth sciences and English. At the end of eight years there is a second rigorous review, which determines the future of the program. It is expected that some programs will have served their purpose and should be discontinued. Other programs may be incorporated into existing departments or may lead to the creation of a new department or a permanent program.

The programs in black studies and Native American studies will be most successful if at the end of eight years the reason for their existence has vanished. They were created in recognition of the fact that existing departments historically have given an exclusively white orientation to subject offerings. As the orientation of courses in literature, history, politics, sociology, and anthropology fully recognize the contributions and special problems of blacks and Native Americans, we will no longer need the specialized programs. For different reasons, the same is likely to be true for the interdisciplinary program in mathematics and the social sciences. With some of the other programs we will need a great deal more experience to decide whether they were only of temporary interest or whether they should be permanently incorporated into the Dartmouth curriculum.

Two additional proposed programs have received discussion in the last two years. One is a program in linguistics and the other a program that has been called "policy design" or "policy studies." Neither of these has yet reached the stage of a concrete proposal to the faculty.

I strongly believe in the value of the interdisciplinary concept. It is a means for an institution to experiment relatively inexpensively with new ideas, without the necessity of creating anything as permanent as a department. It gives opportunities for present faculty members to explore secondary academic interests and to attract to the faculty specialists in new fields. Currently, about six per cent of the total faculty effort is devoted to special programs, and while individual programs may come and go, I favor their continuation at roughly that level.

A new element of academic flexibility was introduced as a result of the Third Century Fund. New faculty positions, known as Third Century Professorships, were created. While they are patterned on research professorships at certain major institutions, their aim is not the expansion of research but the strengthening of teaching at Dartmouth. A faculty member receiving such an appointment is released from half of his normal teaching assignment and uses that time in any way he or she sees fit to make a significant impact on education at the institution To help support this idea, an initiative fund is provided to be used at the sole discretion of the Third Century Professor. Currently three such positions exist within Arts and Sciences, one in the Medical School, and one in the Tuck School. The Arts and Sciences positions have been named for Albert Bradley '15 (sciences), Theodor Geisel '25 (humanities), and John Sloan Dickey '29 (social sciences). The Bradley chair was the first one to be created and was actually filled before I took office. Unfortunately, the Trustees disqualified the incumbent - by electing him President of the College. Currently, Professor Peter Bien of the English Department holds the Geisel chair, and Professor James Hornig of the Chemistry Department will assume the Bradley chair next fall. We hope to announce the appointment of the Dickey Professor later this year.

We can be extremely proud of the quality of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences. As undergraduate education has always been the heart of Dartmouth College, this faculty is our single greatest asset. The outstanding students now attracted to Dartmouth are well served by a faculty of exceptional qualifications and deep devotion to undergraduate education.

Features

-

Feature

FeatureSix Alumni Awards Bestowed

July 1958 -

Feature

FeatureBicentennial Draws Unusual Gifts

OCTOBER 1969 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn Rassias

OCTOBER 1997 -

FEATURE

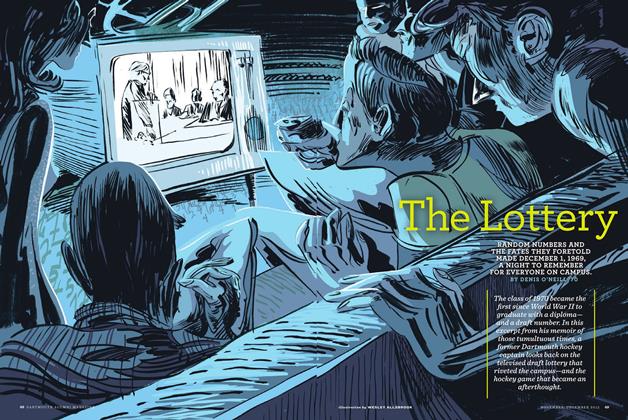

FEATUREThe Lottery

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2013 By DENIS O’NEILL ’70 -

Feature

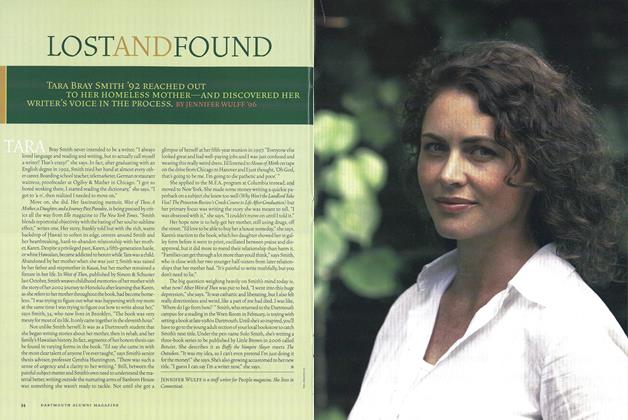

FeatureLost and Found

May/June 2005 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Cover Story

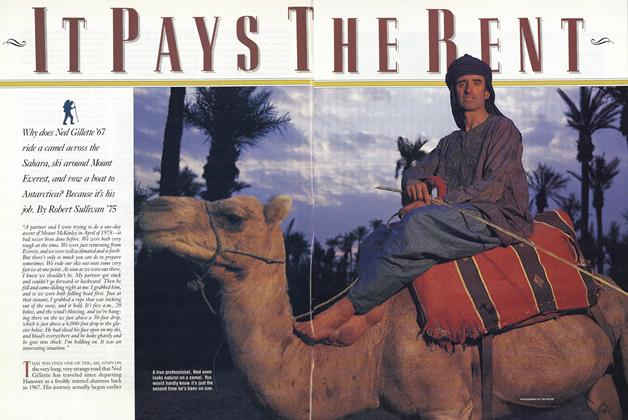

Cover StoryIt Pays The Rent

APRIL 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75