With the pledge of a gift of $30,000 to the College, the Class of 1930 and Dartmouth College have agreed upon the establishment of The Class of 1930 Endowed Lectureship. The following account of the purpose and spirit of the lectureship was written by G. Winchester Stone '30, chairman of the committee named to determine what sort of project the Class should endow.

The Class of 1930 Endowed Lectureship has been conceived to have sufficient elasticity to break, if necessary, the bonds of the formal classroom spiel, or the illustrated travelogue that slightly enlivened a Sunday evening in the church social room or the town hall within the distant memory of some members of our Class. The lecture will be as lively and penetrating as the lecturer, may be as informal as a seminar gathering, and as elongated as a week of dialogue with groups large or small of students, faculty, and the Hanover community. This flexibility, at least, was in the minds of the committee members who suggested the lectureship as a major class project.

We used to think, perhaps, in the late twenties of the day-to-day effects of the course lectures of the David Lambuths, the Kenneth Robinsons, the Benfield Presseys, the McQuilken DeGranges, the Royal Nemiahs, the Griggses, the Hendersons, the Skinners, the Greenes, the Urbans, the Longhursts, Ungers, Riegels. McDuffies, and even the Pattons of the world—the list of excellent teachers was long. But in those days we seldom thought much about the overall purposes of a liberal education—to preserve, to disseminate, and to advance knowledge. We lived upon the stimulation of the moment, riding on the backs of those who had gone before us, who in their maturity contributed to keeping the special process of education going at Dartmouth. And its special flavor then, one supposes, was sparked by two concepts in the mind of President Hopkins—opportunity for the clash of ideas, and opportunity (even in the then isolation of Hanover) of exposure to many options, many folkways, many choices.

When the Baker Library arrived the Hanover experience was really rich. "'Tis not a soul, 'tis not a body that we are training up, but a man, and we ought not to divide him," wrote Montaigne in 1580. "The central aim of a liberal arts college such as Dartmouth," wrote Mr. Hopkins in 1931, "is to develop a habit of mind rather than to impart a given content of knowledge." And this habit of mind he defined as the facility to learn easily, the taste for learning continually, and the will to learn accurately. To further this aim, and to become a true disciple of Montaigne, he organized the accumulated wealth of a long tradition, and supplied us with the playing fields, the tracks, the courts, the courses and trails that were a joy to many; the arts, the music, the books that afforded equal joy; the faculty that could transform the consciousness of the inexperienced young, as well as reaffirm what needed reaffirmation in the magnificent cultural heritage of the western world open to us, and often to restore for us some original forgotten meaning in a text that both reached to the past and opened a door to the future.

One of the possibilities for enrichment in those quite simple days resided in a flow of lecturers from outside Hanover, who spoke in Webster Hall, and whom we were under no obligation to hear save the compulsion of our own budding intellectual curiosity. Some of us at a meeting this past summer recalled the evenings 43 years ago when Louis Mumford spoke of the major and unique contributions of America to the history and perennially changing art of architecture and urban planning, or when Edna St. Vincent Millay read her poems and quipped about the presence of dogs in the audience, or when Sinclair Lewis reeled across the stage, or when Irving Babbitt sought to bring as far north as Hanover his hopes for the "new humanism," or when Bishop Stratton affirmed essential fundamentalism amid the dying echoes of the Scopes trial, or even when an opera company sent its cast and costumes to Dartmouth, Massachusetts instead of to Hanover, yet with a few major voices and co-opted talents of student and townsfolk supers put on a Carmen that was out of sight! One of the real unintentional farces of musical history in Hanover.

Now Hanover no longer abides in isolation. Its community has grown, its interests have broadened, its Hopkins Center has become the focus of intellectual and cultural stimulation north of Boston. Its ski trails, its ice ponds, its playing fields remain, one of them fenced by a gift from the Class of 1930. Its murals of Orozco, once "so daring and surprising, may now be taken for granted, but its exhibitions of art continue and change and refresh them- selves. We even contributed, once, an exhibition of Latin American Art for the edification of the community.

Who knows whether the "Endowed Lectureship" series which the Class is now establishing will bring to the young, as the century moves towards its close, a parallel sense of the varied quality of life which we experienced and now remember with increasing vividness? To the committee which recommended the project (Dickerson, Haffenreffer, Horn, Parker, Scribner, Thompson, and Stone) it seemed that among the options for a class contribution (in addition to increased dollar giving) we might best enable an educational tradition to continue at Dartmouth by the "lectureship" venture. By it we identified a certain kind of intellectualism undying at Dartmouth.

And so we are engaged. We are raising a capital fund of $30,000 to implement the lectureship. The income, amounting to about $1500 annually, will be used to provide housing, travel expenses and honoraria for distinguished men or women who would spend a week on campus, deliver a public lecture, hold a number of seminar sessions, and maintain hours for discussion and consultation. The fund could also be applied to engage distinguished alumni in the non-academic fields, or in fields not supported by Dartmouth curricula. A lawyer, judge, artist, producer, poet, orientalist, statesman, or man of business, for example, in residence for a week might extend the opportunities of curious students to increase their knowledge of procedures, practices, and philosophies of persons successful and active in various walks of life. Students now restless under the requirements of formal class work might welcome such a voluntary extension of the educative process.

The persons chosen to come through the fund will be selected by a Committee appointed by the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences in consultation (as long as the Class lasts) with the Chairman of the Class of 1930. The Committee will include the Dean of the Faculty, at least one other member of the Faculty, one or more undergraduate representatives, and a representative from the Class of 1930. After the Class has ceased to function as a Class, the lectureship will be administered in such fashion as the President and Trustees of the College may determine, it being understood that to the extent practicable the undergraduates will continue to have a voice in the selection process.

Many of us will be curious to learn about the start-up, the feed-back, and early impact of the series. But as we all know, with the right choice (i.e. an imaginative, experienced, door-opening speaker) the influence may, like a nugget of radium, continue in subtle fashion to spark and refresh the mind of the curious listener year after year, even as the Mumfords and Millays sparked us. Continuity of educational opportunity in this fashion was the impulse to which the Class has responded.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureKiewit: A Man-Machine Success Story

April 1972 By Charles J. Kershner -

Feature

FeatureBaseball Chief

April 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureAdvocate for the Aging

April 1972 -

Feature

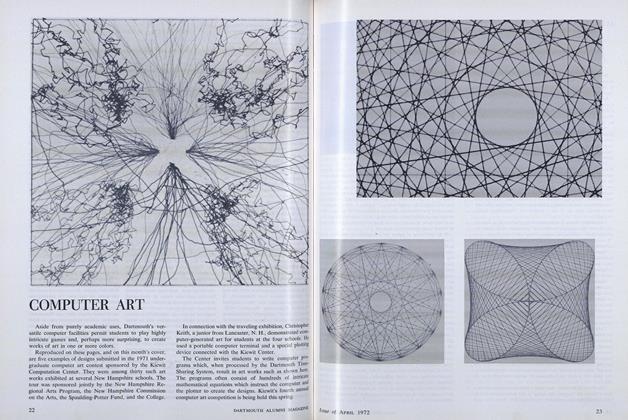

FeatureCOMPUTER ART

April 1972 -

Article

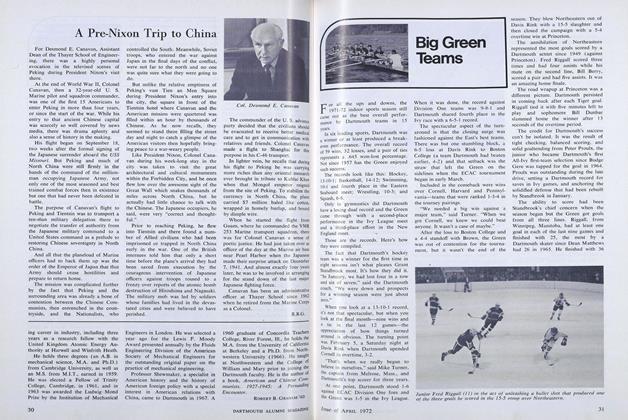

ArticleBig Green Teams

April 1972 By JACK DEGANGE -

Article

ArticleFaculty

April 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40

Article

-

Article

ArticleBridge Honors Knights

May 1961 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

MARCH 1989 -

Article

Article'60s on Saddam

FEBRUARY 1991 -

Article

ArticleA Find For Ripley's

MARCH 1992 -

Article

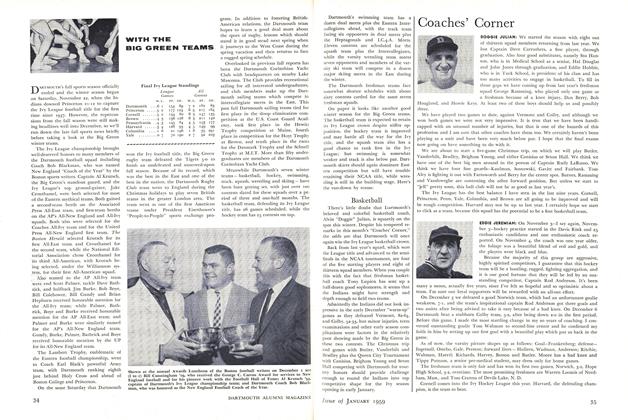

ArticleWITH THE BIG GREEN TEAMS

JANUARY 1959 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth’s Greatest Conservationist

December 1990 By Peter S. Bridges ’53