To redeem American music from the "country cousin" status to which the world of musicology has largely relegated it is the primary objective of the Institute for Studies in American Music at Brooklyn College. It is also a long-time preoccupation of H. WILEY HITCHCOCK '44, its first director, a music historian whose writings lent indirect impetus to its formation last year.

The Institute was established with the announced aim of providing "a suitable academic framework in which to encourage, support, evaluate, and propagate research projects in American music." The New York Times, hailing its birth, put it more succinctly: "Taking American Music Seriously."

"Perhaps no nation in the world is as ignorant of its musical past as our own; on the other hand, no nation has as rapidly expanding a musical present," Hitchcock wrote recently. "Our musical past and present, at many cultural levels—'classical' and 'popular,' cultivated and vernacular, white and black, inner-American and inter-American—demand the kind of investigation, documentation, preservation, and propagation that only a great university can provide."

Reasons for the neglect are historical, some originally deserved, Hitchcock acknowledges, but most badly outdated. Early American "art music" was often derivative, poor copies of European masters. Early musicologists, under traditional Germanic influence, took a narrow view of what constitutes "proper" fields of study. But new approaches to music as reflection of culture as well as artistic monument have opened up vast reservoirs of material in jazz, in the rich ethnic mix of folk, in the new sounds of pop and electronic music. And the condescension toward cultivated American music has lost what legitimacy it had, Hitchcock believes: "This country is producing art music of quality second to none."

As director of the fledgling Institute, he will supervise its growth as a repository of knowledge, a center for research, a clearing house for information of use to scholars and performers, a focal point for students at the four colleges and the Graduate Center which make up the City University of New York. Among high-priority projects are a Monograph Series, a Recording Series, new editions of American composers, bibliographies, oral history projects, radio and television series, and symposia on American music and related interdisciplinary subjects. A newsletter is already filling an abysmal gap in communication among scholars and students in the field.

New York is an ideal location for the Institute, Hitchcock points out. In addition to the music faculties of Brooklyn, Queens, Hunter, and City Colleges and the CUNY Graduate Center, the city affords "incredibly rich research facilities" as well as an unmatched range of concert life. The American Collection of the Research Library of the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center and the Schomburg Collection of Negro Literature and History in Harlem (both branches of the New York Public Library), museum and private libraries, and the collections of radio stations, to be catalogued under Institute auspices, offer unparalleled resources for serious study of American music.

Besides administering Institute affairs, Hitchcock is continuing a teaching career of more than 20 years. He became a teaching fellow at the University of Michigan in 1948 and, staying on after completing his Ph.D., moved up through the professorial ranks. He left Michigan in 1962 to become chairman of the Department of Music at Hunter. A prolific scholar, he is the author of Music in the UnitedStates: A Historical Introduction and numerous articles, editor of Earlier American Music, series editor of Prentice-Hall's 11 -volume History of Music, and American editor of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians.

Though known primarily as an American musicologist, Hitchcock is also an authority on French and Italian baroque. His master's thesis was on American, his doctoral dissertation on French music. His publications mirror the range of his scholarly interests: from "Jazz Improvisation and the European Tradition" to "Lyricism and Italianism in the Elizabethan Madrigal." Earlier recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship and two Fulbright Research Scholarships in Italy, he was back in Florence last fall with his wife, an art historian at Hunter, working on the music of Julio Caccini, a figure in 17th-century Italian opera.

Hitchcock is chairman of the musicologists' committee which is planning programs to celebrate the bicentennial of the Declaration of Independence in 1976. As one of the projects, he will edit the six volumes of music composed by William Billings, an 18th century Bostonian who wove a considerable amount of social commentary and revolutionary fervor into what were ostensibly religious hymns for choral societies. The fact that it will be the first critical edition of the work of any American composer is a startling illustration of the neglect American music has had—a neglect which the Institute and Wiley Hitchcock seek to remedy.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Valedictorian Changes His Mind

May 1972 By ALBERT WILLIAM LEVI '32 -

Feature

FeatureMorton, Kilmarx Elected Charter Trustees

May 1972 -

Feature

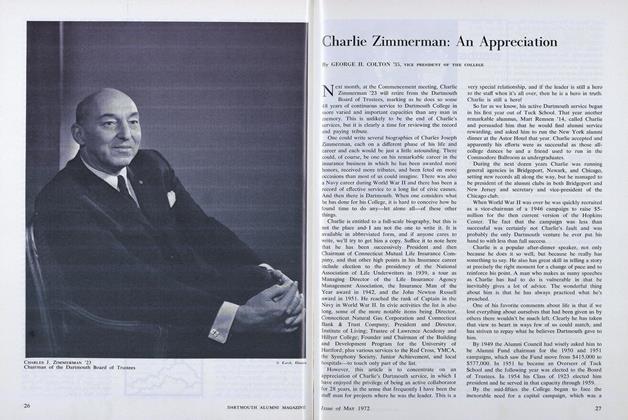

FeatureCharlie Zimmerman: An Appreciation

May 1972 By GEORGE H. COLTON -

Feature

FeatureThe Nautical Nyes

May 1972 By MARY ROSS -

Feature

FeatureTrade Unionist

May 1972 -

Article

ArticleDeaths

May 1972

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Record-Breaking Reunion Week

JULY 1963 -

Feature

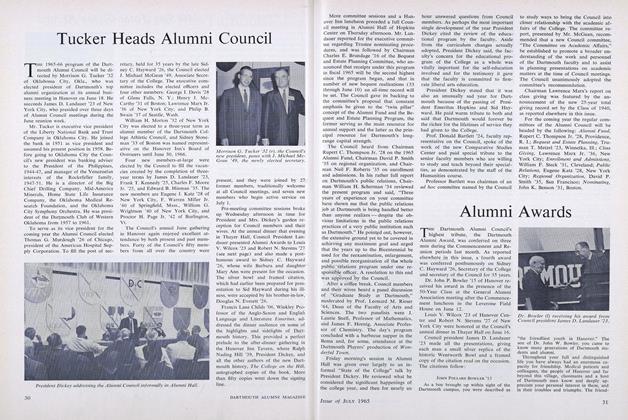

FeatureAlumni Awards

JULY 1965 -

Feature

FeatureThe President's Answers to Some Questions During Radio Interview

DECEMBER 1971 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying (and Laughing) in the Wilderness

Sept/Oct 2005 By BRYANT URSTADT ’91 -

Feature

FeatureNice Work if You Can Get It

December 1995 By DIANE CYR -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNow For The Hard Part

FEBRUARY 1991 By Jay Heinrichs