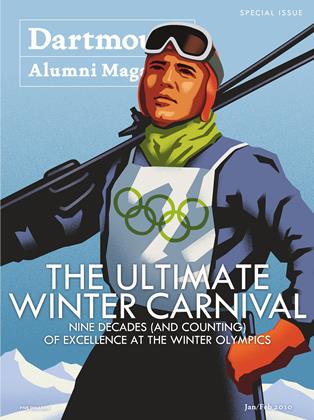

The Ones To Watch

The College has another strong crop of athletes now making plans for Vancouver. Here’s the rundown.

Jan/Feb 2010 Brad Parks ’96The College has another strong crop of athletes now making plans for Vancouver. Here’s the rundown.

Jan/Feb 2010 Brad Parks ’96THE COLLEGE HAS ANOTHER STRONG CROP OF ATHLETES NOW MAKING PLANS FOR VANCOUVER. HERE'S THE RUNDOWN.

Scott Macartney ’01

Despite a frightening crash that smashed his helmet and kept him off skis for months, there’s no quit in this downhiller as he goes for gold at his third Winter Olympics.

If the only thing you knew about Scott Macartney came from roughly 90 seconds of YouTube footage, you’d be surprised he is still upright, much less aspiring to his third Olympic team. The video is easy enough to find. Just start typing “Scott Macar…” into YouTube’s search field, and “Scott Macartney crash in Kitzbühel 2008” pops up in the autofill. Once you click through the graphic content warnings, you too can join the roughly 3 million people worldwide who have viewed the small portion of Macartney’s life that he doesn’t remember.

You can see him whiz through a speed trap at the Kitzbühel World Cup downhill course at 87.74 miles per hour, the fastest time recorded that day. You can see him hit the final jump and twist high into the air. Then you hear the Austrian announcer say, “helmet gebrocht” (helmet breaking), which is what happened when Macartney’s head hit the ice. In another version an announcer just starts whispering “mein Gott, mein Gott, mein Gott” as the gruesome crash unfolds.

There’s yet another YouTube video of Macartney being airlifted off the mountain to a hospital in Innsbruck, where he was placed in a medically induced coma. It was January 19, 2008, Macartney’s 30th birthday. His coaches and doctors passed the night thankful it appeared he would make it to 31.

Had that been the final race of Macartney’s career, he would have retired with a resume matched by only a handful of Americans who ever put on skis. In his two Olympics he accumulated five top-30 finishes, including a seventh place in the Super-G at 2006 in Torino, a mere quarter-second outside the medals. He had twice medaled in World Cup competitions.

What’s more, he had plenty of things beyond competitive skiing with which he could fill his retirement. In addition to his degree from a reputable college, he had the contacts he made from serving on the U.S. Ski and Snowboard Association board of directors, and he and Dartmouth buddy Derek Draper ’02 had begun planning an online ski coaching business. He was also involved with World Cup Dreams, a nonprofit foundation that helps fund up-and-coming American skiers. He had plenty else to do that wouldn’t involve slamming into ice at close to 90 miles per hour.

But quitting never occurred to Macartney. With no swelling in his brain—the helmet, breaking as it is designed to do, absorbed the worst of the crash—he was brought out of the coma the next day. Four days later he left the hospital. Within a week and a half, even though he was still in something of a fog, family and friends practically had to restrain him from getting back to strenuous training. Four months later, with his cognitive functioning fully returned, Macartney started sliding around on skis again.

“That was one of the most dramatic crashes in the history of the sport,” says Bryon Friedman ’02, Macartney’s roommate at Dartmouth and on the U.S. ski team. “I probably would have quit the sport on the spot if I had been there to see that crash. But I never heard Scott talk once about quitting.”

Macartney’s parents, Laurie and John, a schoolteacher and a principal who still live in Scott’s hometown of redmond, Washington, didn’t even bother asking him to consider retirement. “I knew darn well he was going to keep racing anyway,” Laurie says.

This, after all, was the kid who would come home from first grade with drawings of himself skiing in a downhill suit with Olympic rings in the background. From the time he was in junior high school he slept under a poster of Tiger Shaw ’85 with the words “Tiger Shaw, Olympic Skier, Dartmouth Graduate.” That pretty much explains how he ended up in Hanover. Driven? Motivated? That doesn’t begin to cover it. Skiing was his life. It would take a lot more than a gruesome crash to get him off the slopes. He moved on.

it’s just that no one else could. when he returned to the World Cup circuit for the 2008-09 season the crash was all anyone asked about. Finally, after an ambush interview by an Austrian newspaper reporter—who promised no questions about Kitzbühel, then presented Macartney with the “gift” of 9-by-11 glossy pictures of the crash so the newspaper could photograph him looking at them—Macartney decided he was no longer answering Kitzbühel questions.

“It’s an easy story to sell, it’s a story that gathers a lot of attention, it was a spectacular crash. I understand all that,” says Macartney. “But as an athlete who is still trying to compete at the highest level I have to look forward, not back.”

Soon he had bigger problems. At Macartney’s next race, just as he was finally returning to form, he landed on the back of his skis after a jump, tearing his ACL, injuring his meniscus and ending his season. In an unfortunate twist, that accident—which Macartney calls “the most annoying and ill-timed injury of my career”—is now a far greater threat to Macartney’s bid for a third Olympics. He underwent reconstructive surgery last January, receiving a ligament graft from a cadaver, and is just now getting back to competitive skiing. The final team won’t be selected until a few weeks before Vancouver. But no one doubts Macartney when he says he’ll be full strength by then.

“The beauty of Scott is you just add water, and the muscle appears on that guy,” says Friedman. “He looks like a running back—his legs are huge, his upper body is huge. He’s just super strong.”

And at 31, an age when downhillers are in their prime, he’s been there before.

“Salt Lake [in 2002] was all about the experience of being in the Olympics,” Macartney says. “Torino was all about having a chance to medal.”

Maybe that makes the third time around all about winning a medal—the only kind of YouTube footage Macartney hopes the world sees of him in the future.

Carolyn Treacy Bramante ’06

When this multi-tasker discovered the biathlon it was “love at first shot.” now she has set her sights on her second Winter Games.

It’s all about changing in the parking lot. This is one of the ways Carolyn Treacy Bramante explains how she manages handling the training load of an Olympic athlete while pursuing a medical degree and a master’s in public health and a variety of research projects, all while organizing a full slate of community outreach activities.

So just say it’s a typical day in the life of the University of Minnesota medical student/U.S. biathlon team member/volunteer activist. She starts with a two-hour roller ski run. Then she attends lectures. Then she scoots off to a two-hour interval training session. Then she sneaks into the lab for a while. Then she volunteers at a free clinic at night. How does she pack it all in? Easy. She changes in the parking lot.

Another example: Two winters ago Bramante won the City of Lakes Loppet, a 35-kilometer cross-country ski race in Minneapolis, barely pausing at the finish line to accept her medal. Then she jumped into her car to catch a flight to Washington, D.C., where—as the president of her school’s chapter of Physicians for Human Rights—she had been selected to participate in a national summit on HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. She made the flight with time to spare. Why? She changed in the parking lot.

“That’s just an example of a little thing you can do to save time, because then you don’t lose 15 minutes going back home and changing,” says Bramante. “You do that six times and you’ve just gained an hour and a half.”

It’s an acute sense of time management that seems to have been with Bramante since, well, birth. Her parents, Anne and Kevin Treacy, swear that the day their daughter was born she propped herself up on her forearms and had a look around, as if she just couldn’t wait to conquer everything she saw.

“It made her an incredibly difficult toddler,” says Anne. “She was never a kid who would sit still for anything. The only time she ever allowed herself to be held or cuddled was when she got sick.”

Climbing trees and playing on monkey bars eventually gave way to swimming in the summer and cross-country skiing in the winter. At age 14 she attended a U.S. biathlon recruiting camp. It was, says Bramante, now 27, “love at first shot.”

After all, biathlon is the perfect sport for the serial multi-tasker. While sometimes misunderstood—one popular joke is that biathlon is for triathletes who can’t swim—biathlon marries Nordic skiing (which requires strength and endurance) with target shooting (which requires steady hands and steely concentration). It’s a bit like running a half-marathon and stopping every couple of miles to thread a series of really small needles.

For Bramante that just meant it was a good challenge. She threw herself into junior competitions and made the national team. In 2002 she was a member of a relay team that earned a silver medal at the World Junior Biathlon Championships—the first relay medal ever won by a U.S. team at a world championship competition.

She matriculated at Dartmouth the next fall, taking full advantage of the D-Plan’s flexibility to continue training with the national team. In 2006 she qualified for the Olympics by the narrowest of margins—a perfect performance on her last set of targets at the U.S. trials proved to be the difference—then ended up anchoring a U.S. relay team that finished 15th, its best Olympic showing ever. Bramante’s signature achievement was starting 30 seconds behind the Canadian team but finishing 49 seconds ahead of it.

After graduating in 2007 she and her husband, Anthony Bramante ’06—they met through the Dartmouth Outing Club, got engaged atop Mount Moosilauke and were married in July 2006—spent their “honeymoon” teaching english in Siberia and formulating plans for the future. Anthony shocked friends and family by joining the Marines (an intelligence officer with an interest in military policy, he is now home from his first tour in Iraq). Carolyn, who was already notorious among her teammates for spending her “down” time at World Cup events studying, shocked exactly no one by going off to medical school.

“Staying involved academically keeps me from overtraining,” she says. “Like today, I did four and a half hours of training in two huge interval sessions. But tomorrow I’ll just train for an hour and a half or two hours.”

Oh. Is that all?

“When I started med school,” she explains, “I sort of had to cut out all the fluff workouts.”

Of course merely studying and training aren’t enough. Bramante comes from a Catholic family that ingrained the importance of charity at a young age, whether it was her grandmother constantly volunteering or her ophthalmologist father founding a program to provide free eye care on the Caribbean island of St. Vincent. At Dartmouth Bramante helped start a chapter of Unite for Sight, an eye-care outreach group, was a student leader in the DOC and volunteered with the Tucker Foundation.

“She just gets involved in everything,” says Cami Thompson, Dartmouth’s cross-country coach, for whom Bramante skied on and off during her five years in and out of Hanover. “She’s one of those people who wants to save the world.”

Her parents, who still live in Bramante’s hometown of Duluth, Minnesota, say their daughter never stops seeing—or inventing—ways to help people. Her current project, a medical outreach program for the homeless, started when, while delivering free meals to the homeless during the holidays, she was struck by the paucity of their healthcare.

“As an Olympic athlete I have access to all these resources and get to spend all this time focusing on keeping my body healthy,” she says. “And here were these people who didn’t even get access to the most basic resources.”

So last year she co-founded Inter-professional Street Outreach Program (ISTOP), a program that sends medical students and their professors into Minneapolis’ toughest neighborhoods to provide free healthcare. ISTOP now has 259 volunteers making trips into the field four times a month. (Volunteers use Bramante’s official Olympics duffel bag to haul medical supplies.) Jacob Feigal, ISTOP’s co-founder, attributes the program’s success to Bramante’s bubbly personality, disarming leadership style and nonstop energy.

“Med school is full of busy people, but she’s the busiest person in the room,” says Feigal. “We just laugh at her level of activity.”

Not that Bramante ever hears them. By that point she’s already in the parking lot, changing for whatever comes next.

Brad Parks is a freelance writer and author. His first novel, Faces of the Gone: A Mystery, is due out from St. Martin’s Press in December.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureHow Does It Feel?

January | February 2010 By LEANNE MIRANDILLA ’10 -

Feature

FeatureCampbell’s Coup

January | February 2010 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Feature

FeatureBeyond the Glory

January | February 2010 By SARAH TUETING ’98 -

Feature

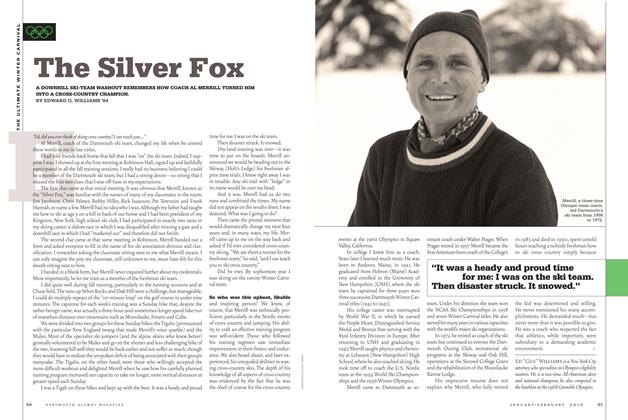

FeatureThe Silver Fox

January | February 2010 By EDWARD G. WILLIAMS ’64 -

Feature

FeatureFree Ride

January | February 2010 By ED GRAY ’67 -

Feature

FeatureGames Changers

January | February 2010 By LISA FURLONG

Brad Parks ’96

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDifferent Strokes

May/June 2002 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Sports

SportsThree Times a Coach

Mar/Apr 2006 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Feature

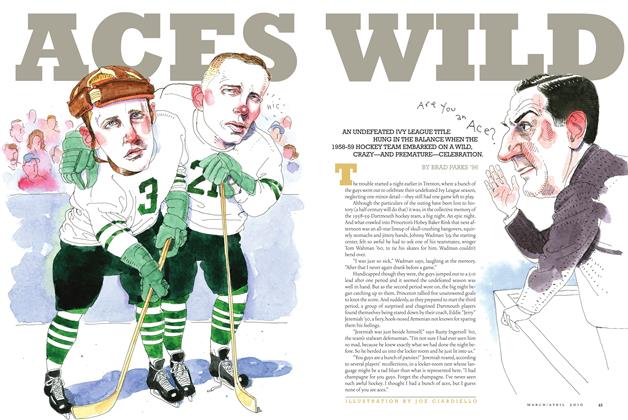

FeatureAces Wild

Mar/Apr 2010 By BRAD PARKS ’96 -

Feature

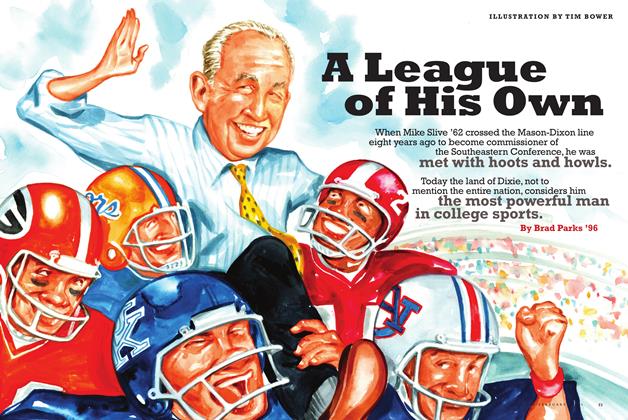

FeatureA League of His Own

Jan/Feb 2011 By Brad Parks ’96 -

Sports

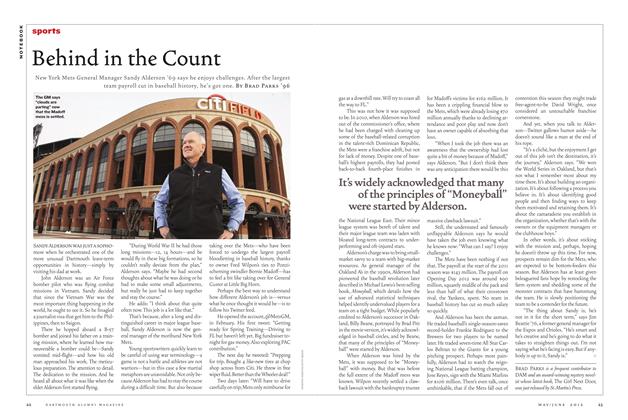

SportsBehind in the Count

May/June 2012 By Brad Parks ’96 -

SPORTS

SPORTSGame Changer

SEPTEMBER | OCTOBER 2018 By BRAD PARKS ’96

Features

-

Feature

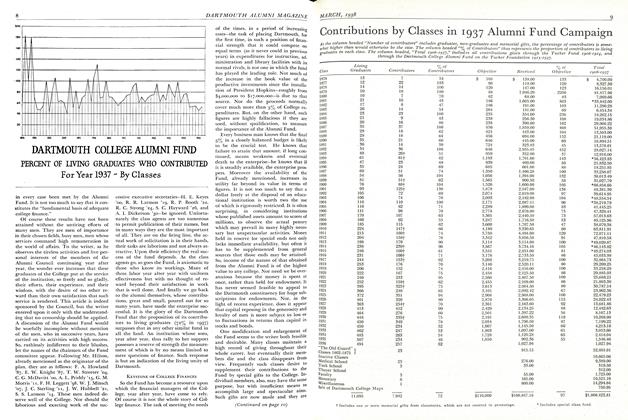

FeatureContributions by Classes in 1937 Alumni Fund Campaign

March 1938 -

Feature

FeatureDr. Gilbert Horton Mudge Named Dean of Medical School

January 1962 -

Feature

FeatureReport of the Office of Development

September 1975 -

Feature

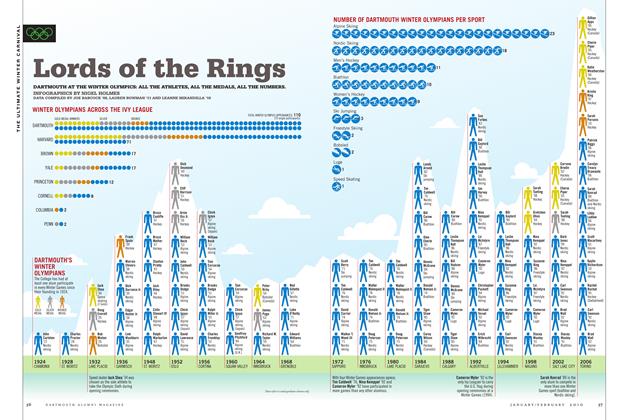

FeatureLords of the Rings

Jan/Feb 2010 -

Feature

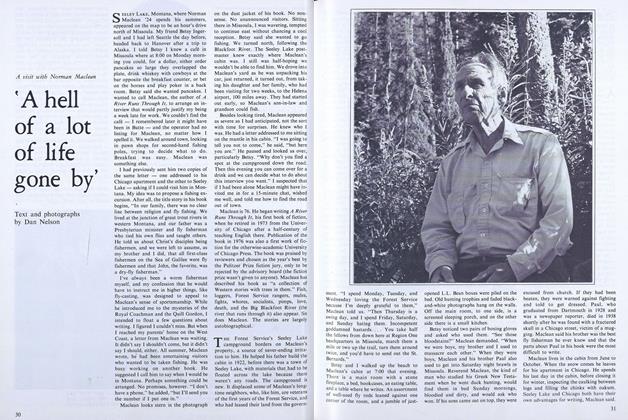

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson