Dartmouth in Washington

JULY 1972 MICHAEL SORICE '74, MICHAEL JENNINGS '72, JAMES KLOPPENBERG '73A Student Communication

In the words of the president of Stanford University, there has developed "a dangerous and ever-growing disenchantment with a political system" which cannot end our involvement in a war which is "immoral at worst, and a failure at best." President Nixon's speech on May 8, making public his decision to increase the bombing of North Vietnam to include non-military targets and to impose a naval blockade upon North Vietnam produced an immediate response among many students and mem- bers of the faculty at Dartmouth College. The apparently negligible effect of previous student opposition to the war in Vietnam had led many members of the Dartmouth community to an increasing sense of futility. Disillusioned with the lack of receptivity to their opinions, tens of thousands of dissenting Americans had been driven to apathy and silence. Following the latest escalation of the war, observers had interpreted the initial absence of student response as an indication of support for the President's policies. We felt this to be inaccurate, and set about to express our discontent with Nixon's conduct of the war and his continued usurpation of Congressional war-making powers.

President Nixon's policy is predicated on the belief that it commands wide public support. By voicing our protest, we hoped to refute this notion of general consent. That protest could receive only limited response were it to remain in Hanover. Therefore, over 150 Dartmouth students and faculty members optimistically attempted to attain what we considered to be the apex of individual involvement within the political process: a personal visit to Capitol Hill.

At the apex, we found the legislators purportedly representing our interests to be generally unresponsive, often condescending, and even, in many cases, ignorant of the Vietnam situation and the legislation then before them concerning that situation. At times, appointments with the Congressmen themselves proved impossible to get, and groups of five to ten people from Dartmouth usually found themselves confronted with a familiar Washington phenomenon known as the "Legislative Assistant." If conveyed by the "L.A.," the form in which our views were finally received by the legislator was problematical at best.

In our discussions with pro-administration legislators, we tried, first of all, to make them aware of the existence of support for an alternative to war in Southeast Asia, and secondly, to convince them that erosion of their constituency was to be the return on an undesired continuation of the war. With respect to anti-war Congressmen, we urged them to augment their "no" votes with a more active role in the making of strong, effective anti-war legislation. Lastly, we attempted to influence uncommitted "swing" votes toward the side of opposition to the Vietnam war.

After a period of a few weeks, the lack of courtesy and the generally negative reception accorded most young lobbyists began to turn us back to Hanover and a concerned attention to further developments.

In the course of the two-week period spent lobbying in Washington, we became more and more familiar with the slow, painstaking process through which the war issue is dealt with by our Congress. We also became aware of the discourteous manner in which young dissenters are received. It is of no surprise, then, that many of us now have come to sympathize whole-heartedly with the following statement made by the president of Amherst College: "I speak out of frustration and deep despair. I do not think that words will change the minds of the men in power, and I do not care to write letters to the world. What I protest is that there is no way to protest."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

July 1972 -

Feature

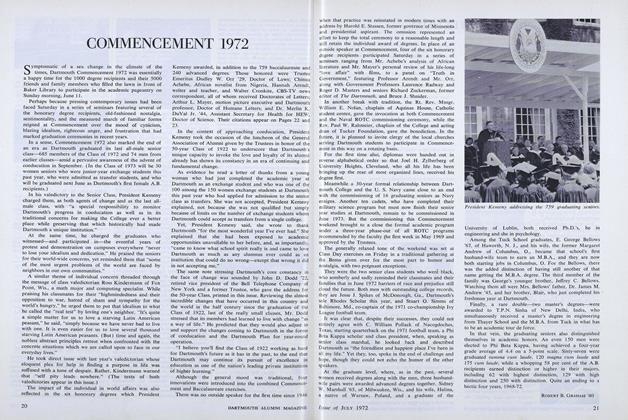

FeatureCOMMENCEMENT 1972

July 1972 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

July 1972 -

Feature

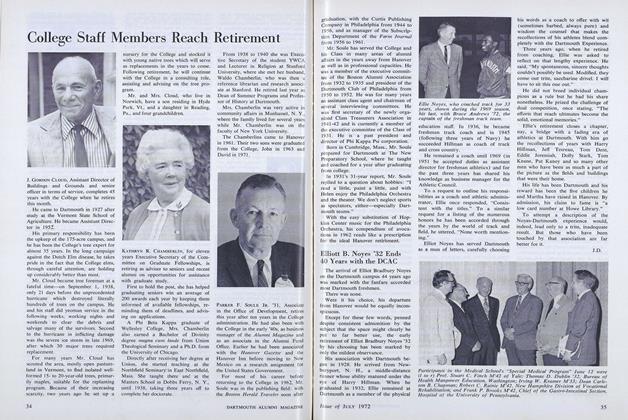

FeatureCollege Staff Members Reach Retirement

July 1972 By J.D. -

Feature

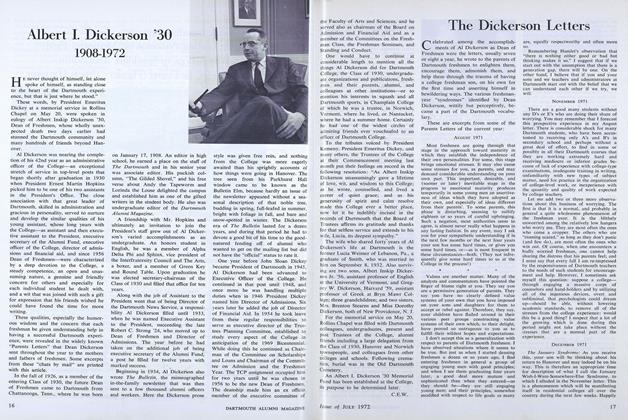

FeatureAlbert I. Dickerson '30 1908-1972

July 1972 By C.E.W. -

Feature

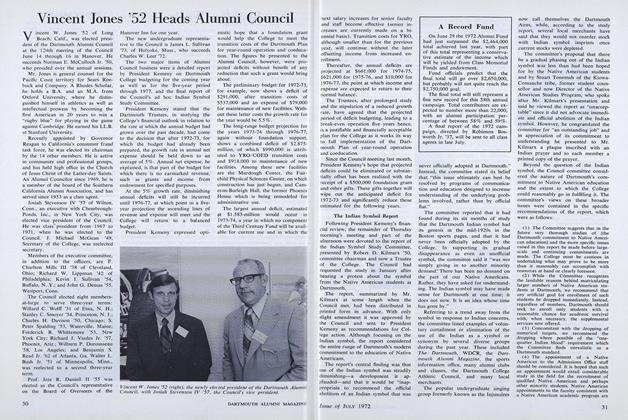

FeatureVincent Jones 52 Heads Alumni Council

July 1972