For most inhabitants of the North Country, splitting a winter's worth of wood reducing a truckload of logs to five or six cords of firewood is a monumental task likely to take several months of weekends. But not for Jim Taylor '74, who, local legend has it, once bet that he and his axe could split a full truckload of wood in one day . . . and won. Taylor is also known around Enfield, N.H., for regularly turning his talents to helping out elderly neighbors faced with an empty woodshed and a plummeting thermometer.

But Taylor is neither a masochist nor a diehard do-gooder. Although he earns his living as a personnel manager at a computer firm, he puts his heart into his avocation as one of the Northeast's top woodsmen. From mid May till late October, Taylor spends his weekends axe-throwing, bucksawing, splitting, crosscutting, log-loading, and speed-chopping his way through collegiate, county fair, and professional logging competitions from Hay ward, Wise., to Fryeburg, Maine. And in his spare time, he coaches the DOC woodsmen teams.

Taylor has been a devotee of the woodsmen's sport since he was hastily recruited in the spring of his freshman year to round out the Dartmouth team. Though he'd never before then swung an axe in competition, he has since acquired a considerable measure of fame in the field, copping many titles for himself individually (including the North American crosscutting championship in 1982 and the New England bucksawing championship for the past three years) as well as for the DOC teams under his guidance.

During Taylor's own undergraduate years, the DOC teams were considered the doormat of woodsmen's competitions intellectuals dabbling at being woodsmen while vying against some of the best forestry students in the Northeast. Today, Dartmouth is the team to watch: At a recent meet in Hanover, both the men's and women's alumni teams and the women undergraduates walked away with top honors, while the undergraduate men took a respectable second.

Much of Dartmouth's turnaround can be credited to Taylor's coaching "they now have more and better practice" and to his knowledge of the tools of the trade. As with any sport that requires perfection of a simple motion over an extended time, good equipment can make a great deal of difference. As Taylor explains, "It's a multiplying factor the competitor's skill times the quality of the equipment." He keeps his own equipment in flawless shape. Unlike the local hardware store variety of axe, Taylor's are all made in Australia expressly for competition. They are patterned and curved to cut through wood fibers as quickly as possible, yet are so delicate that if they hit a knot they would break. His half-dozen axes, each designed specifically either to chop (against the grain) or to split (with the grain), are carefully stored in a beautiful wooden case. And an axe is carefully touched up with a whetstone just prior to being used.

With his saw blades, Taylor is even more particular. He is one of the very few competitors who files his own saws. Because so much of the woodsman's craft is in honing logging skills long since outdated by chainsaws, hydraulic splitters, and other mechanized equipment, the techniques both of using and of maintaining the tools have had to be resurrected. John Carney, an old-timer from northern Maine, respected Taylor enough to teach him the fine points of saw-blade filing. That knowledge has paid off, for Taylor is probably the best buck-sawyer in the country, and he and his partner, Don Quigley, a UNH forestry professor, are among the top North American competitors in two-person crosscutting. At a recent competition in Laconia, N.H., Taylor sawed two "cookies" off a piece of eight-by-eight pine in just over six seconds. Most of the competitors took closer to 30 seconds to do the same task.

There is some financial payback in competing for Taylor, but not enough to call it a break-even sport. By the end of this year he will probably have taken $1,500 in prize money, but he will have driven over 15,000 miles to do it. "It's the people I do it with, my own competitive streak, and the fact that it's fun that keep me competing," Taylor readily admits. "It is also one of the few professional sports where good sportsmanship prevails." Competitors are continually cheering each other on, sharing information about equipment (as well as actual whetstones and WD-40), and complaining about the wood ("part of the sport").

Taylor easily foresees himself competing for the rest of his life. With a recent move to Manchester, he probably won't be able to continue to coach the DOC teams, but he will undoubtedly keep generating a ten-foot-high mountain of "cookies" made from practice cuts each summer. "It is something you can get better at." In fact, most good choppers (one of Taylor's weaker events) are over 40. "There is a lot to learn about how to read a log and there's no such thing as a guaranteed win you never know when there will be a hidden knot or even a bullet."

Taylor concludes by telling of the old-time New Zealander who was the best sawyer in the world until the day he died. Clearly, Jim Taylor would love to have that be his epitaph, too.

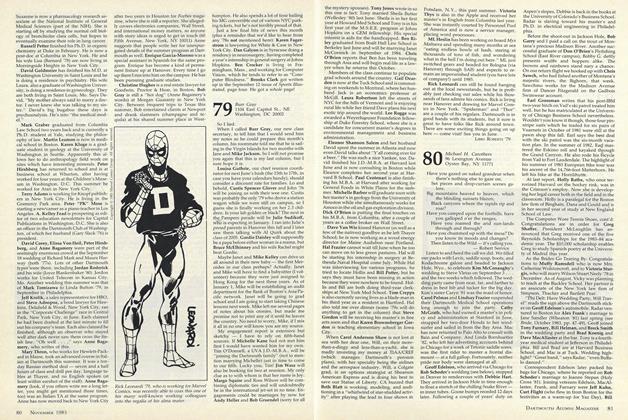

Jim Taylor '74, left, and his partner in the two-person crosscut saw event make quick work of atimber during the Old Time Woodmen's Contest at the 1982 Cornish, N.H., Fair, at whichTaylor took the top prize.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

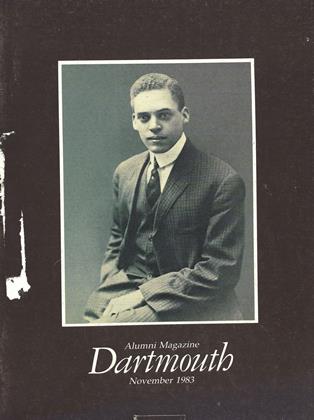

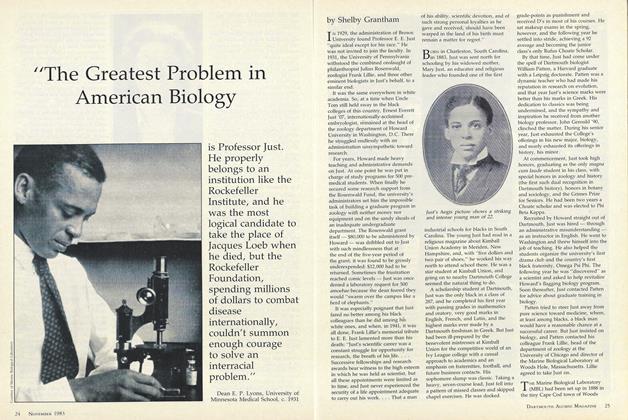

Feature"The Greatest Problem in American Biology

November 1983 -

Feature

FeatureGiving the Rush to the Record books

November 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

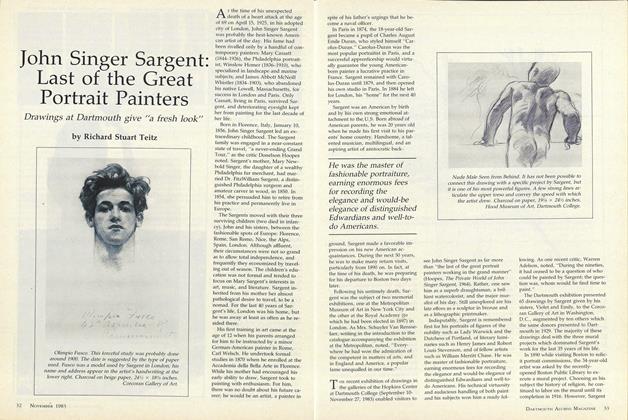

FeatureJohn Singer Sargent: Last of the Great Portrait Painters

November 1983 By Richard Stuart Teitz -

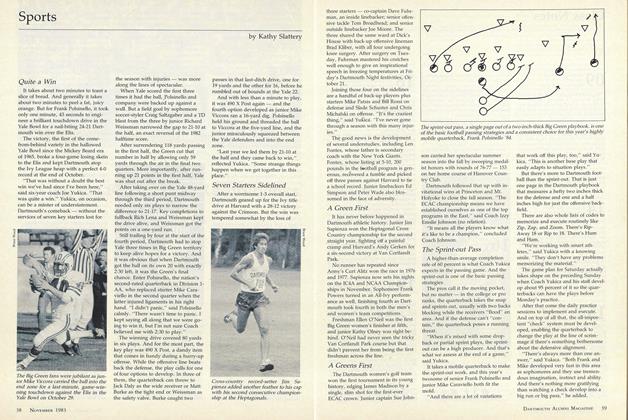

Sports

SportsSports

November 1983 By Kathy Slattery -

Books

BooksAll Biology Is Indebted . . .

November 1983 By Peter Smith -

Class Notes

Class Notes1979

November 1983 By Burr Gray

Nancy Wasserman '77

-

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorLetters to the Editor

APRIL 1978 -

Letters to the Editor

Letters to the EditorOn Wise Teachers

February 1992 -

Article

ArticleTrott Talks Barbering

November 1980 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Books

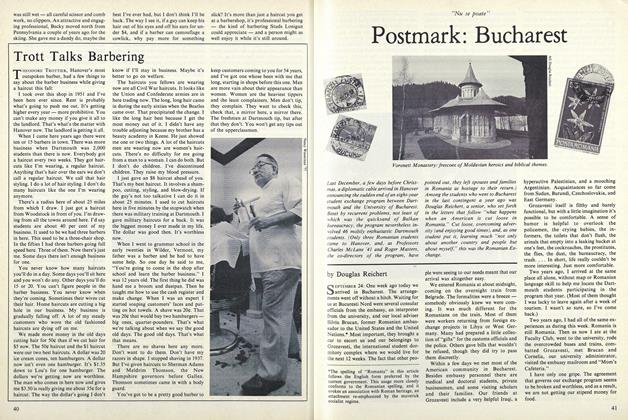

BooksImages

APRIL • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Article

ArticleWhen Right Time Rocks, Good Times Roll

June • 1985 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

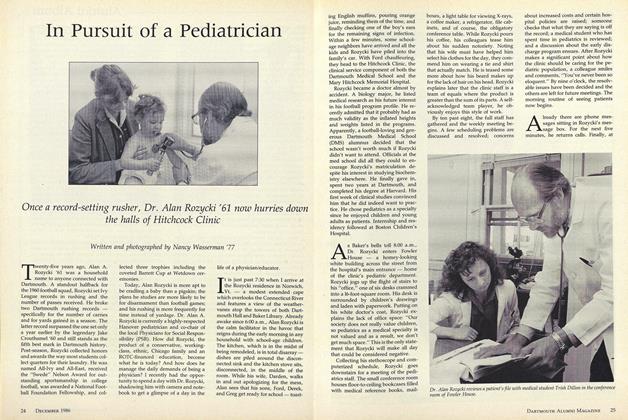

FeatureIn Pursuit of a Pediatrician

DECEMBER • 1986 By Nancy Wasserman '77

Article

-

Article

ArticleYE GLORIOUS SPORT OF RUSHING

November, 1930 -

Article

ArticleWar Measures Adopted

January 1942 -

Article

ArticleCompensation Advance

June 1957 -

Article

ArticleMarvelous Search

October 1978 -

Article

ArticleANNUAL MEETING OF THE DARTMOUTH SECRETARIES ASSOCIATION

April 1917 By Eugene D. Towler '17, W. J. TUCKER. -

Article

ArticleTHE NEED FOR UNUSUALNESS IN THE WORK OF THE COLLEGE

November 1917 By Hopkins