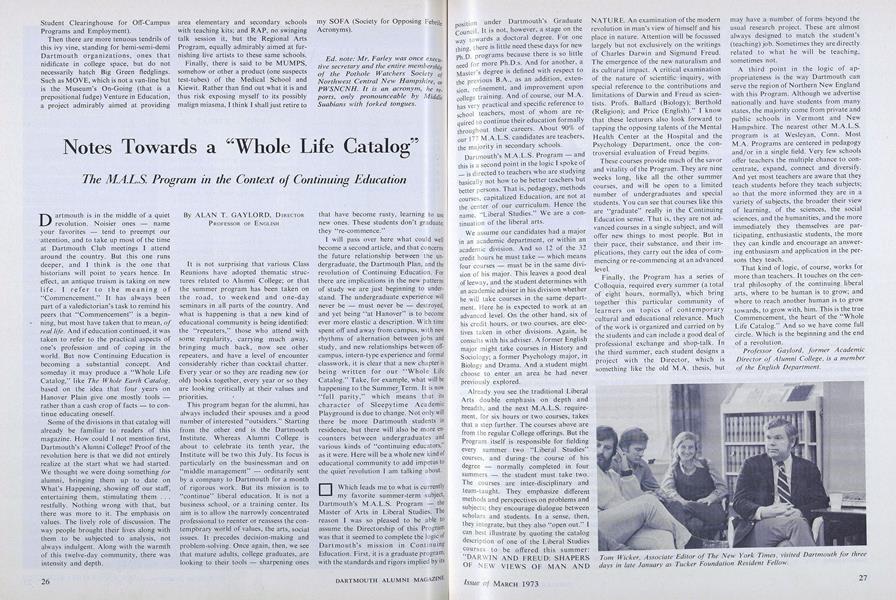

The M.A.L.S. Program in the Context of Continuing Education

PROFESSOR OF ENGLISH

Dartmouth is in the middle of a quiet revolution. Noisier ones - name your favorites - tend to preempt our attention, and to take up most of the time at Dartmouth Club meetings I attend around the country. But this one runs deeper, and I think is the one that historians will point to years hence. In effect, an antique truism is taking on new life. I refer to the meaning of "Commencement." It has always been part of a valedictorian's task to remind his peers that "Commencement" is a beginning, but most have taken that to mean, ofreal life. And if education continued, it was taken to refer to the practical aspects of one's profession and of coping in the world. But now Continuing Education is becoming a substantial concept. And someday it may produce a "Whole Life Catalog," like The Whole Earth Catalog, based on the idea that four years on Hanover Plain give one mostly tools rather than a cash crop of facts - to continue educating oneself.

Some of the divisions in that catalog will already be familiar to readers of this magazine. How could I not mention first, Dartmouth's Alumni College? Proof of the revolution here is that we did not entirely realize at the start what we had started. We thought we were doing something for alumni, bringing them up to date on What's Happening, showing off our staff, entertaining them, stimulating them ... restfully. Nothing wrong with that, but there was more to it. The emphasis on values. The lively role of discussion. The way people brought their lives along with them to be subjected to analysis, not always indulgent. Along with the warmth of this twelve-day community, there was intensity and depth.

It is not surprising that various Class Reunions have adopted thematic structures related to Alumni College; or that the summer program has been taken on the road, to weekend and one-day seminars in all parts of the country. And what is happening is that a new kind of educational community is being identified: the "repeaters," those who attend with some regularity, carrying much away, bringing much back, now see other repeaters, and have a level of encounter considerably richer than cocktail chatter. Every year or so they are reading new (or old) books together, every year or so they are looking critically at their values and priorities.

This program began for the alumni, has always included their spouses and a good number of interested "outsiders." Starting from the other end is the Dartmouth Institute. Whereas Alumni College is about to celebrate its tenth year, the Institute will be two this July. Its focus is particularly on the businessman and on "middle management" - ordinarily sent by a company to Dartmouth for a month of rigorous work. But its mission is to "continue" liberal education. It is not a business school, or a training center. Its aim is to allow the narrowly concentrated professional to reenter or reassess the contemporary world of values, the arts, social issues. It precedes decision-making and problem-solving. Once again, then, we see that mature adults, college graduates, are looking to their tools - sharpening ones that have become rusty, learning to use new ones. These students don't graduate: they "re-commence."

I will pass over here what could well become a second article, and that concerns the future relationship between the undergraduate, the Dartmouth Plan, and the revolution of Continuing Education. For there are implications in the new patterns of study we are just beginning to understand. The undergraduate experience will never be - must never be - destroyed, and yet being "at Hanover" is to become ever more elastic a description. With time spent off and away from campus, with new rhythms of alternation between jobs and study, and new relationships between offcampus, intern-type experience and formal classwork, it is clear that a new chapter is being written for our "Whole Life Catalog." Take, for example, what will be happening to the Summer Term. It is now "full parity," which means that its character of Sleepytime Academic Playground is due to change. Not only will there be more Dartmouth students in residence, but there will also be more encounters between undergraduates and various kinds of "continuing educators," as it were. Here will be a whole new kind of educational community to add impetus to the quiet'revolution I am talking about.

Which leads me to what is currently my favorite summer-term subject, Dartmouth's M.A.L.S. Program - the Master of Arts in Liberal Studies. The reason I was so pleased to be able to assume the Directorship of this Program was that it seemed to complete the logic of Dartmouth's mission in Continuing Education. First, it is a graduate program, with the standards and rigors implied by its position under Dartmouth's Graduate Council. It is not, however, a stage on the way towards a doctoral degree. For one thing, there is little need these days for new ph D. programs because there is so little need for more Ph.D.s. And for another, a Master's degree is defined with respect to the previous 8.A., as an addition, extension. refinement, and improvement upon college training. And of course, our M.A. has very practical and specific reference to school teachers, most of whom are required to continue their education formally throughout their careers. About 90% of our 177 M.A.L.S. candidates are teachers, the majority in secondary schools.

Dartmouth's M.A.L.S. Program - and this is a second point in the logic I spoke of - is directed to teachers who are studying basically not how to be better teachers but better persons. That is, pedagogy, methods courses, capitalized Education, are not at the center of our curriculum. Hence" the name, "Liberal Studies." We are a continuation of the liberal arts.

We assume our candidates had a major in an academic department, or within an academic division. And so 12 of the 32 credit hours he must take - which means four courses - must be in the same division of his major. This leaves a good deal of leeway, and the student determines with an academic adviser in his division whether he will take courses in the same department. Here he is expected to work at an advanced level. On the other hand, six of his credit hours, or two courses, are electives taken in other divisions. Again, he consults with his adviser. A former English major might take courses in History and Sociology; a former Psychology major, in Biology and Drama. And a student might choose to enter an area he had never previously explored.

Already you see the traditional Liberal Arts double emphasis on depth and breadth, and the next M.A.L.S. requirement, for six hours or two courses, takes that a step further. The courses above are from the regular College offerings. But the Program itself is responsible for fielding every summer two "Liberal Studies" courses, and during- the course of his degree - normally completed in four summers - the student must take two. The courses are inter-disciplinary and team-taught. They emphasize different methods and perspectives on problems and subjects; they encourage dialogue between scholars and students. In a sense, then, they integrate, but they also "open out." I can best illustrate by quoting the catalog description of one of the Liberal Studies courses to be offered this summer: "DARWIN AND FREUD: SHAPERS OF NEW VIEWS OF MAN AND NATURE. An examination of the modern revolution in man's view of himself and his place in nature. Attention will be focussed largely but not exclusively on the writings of Charles Darwin and Sigmund Freud. The emergence of the new naturalism and its cultural impact. A critical examination of the nature of scientific inquiry, with special reference to the contributions and limitations of Darwin and Freud as scientists. Profs. Ballard (Biology); Berthold (Religion); and Price (English)." I know that these lecturers also look forward to tapping the opposing talents of the Mental Health Center at the Hospital and the Psychology Department, once the controversial evaluation of Freud begins.

These courses provide much of the savor and vitality of the Program. They are nine weeks long, like all the other summer courses, and will be open to a limited number of undergraduates and special students. You can see that courses like this are "graduate" really in the Continuing Education sense. That is, they are not advanced courses in a single subject, and will offer new things to most people. But in their pace, their substance, and their implications, they carry out the idea of commencing or re-commencing at an advanced level.

Finally, the Program has a series of Colloquia, required every summer (a total of eight hours, normally), which bring together this particular community of learners on topics of contemporary cultural and educational relevance. Much of the work is organized and carried on by the students and can include a good deal of professional exchange and shop-talk. In the third summer, each student designs a project with the Director, which is something like the old M.A. thesis, but may have a number of forms beyond the usual research project. These are almost always designed to match the student's (teaching) job. Sometimes they are directly related to what he will be teaching, sometimes not.

A third point in the logic of appropriateness is the way Dartmouth can serve the region of Northern New England with this Program. Although we advertise nationally and have students from many states, the majority come from private and public schools in Vermont and New Hampshire. The nearest other M.A.L.S. program is at Wesleyan, Conn. Most M.A. Programs are centered in pedagogy and/or in a single field. Very few schools offer teachers the multiple chance to concentrate, expand, connect and diversify. And yet most teachers are aware that they teach students before they teach subjects; so that the more informed they are in a variety of subjects, the broader their view of learning, of the sciences, the social sciences, and the humanities, and the more immediately they themselves are participating, enthusiastic students, the more they can kindle and encourage an answering enthusiasm and application in the persons they teach.

That kind of logic, of course, works for more than teachers. It touches on the central philosophy of the continuing liberal arts, where to be human is to grow; and where to reach another human is to grow towards, to grow with, him. This is the true Commencement, the heart of the "Whole Life Catalog." And so we have come full circle. Which is the beginning and the end of a revolution.

Tom Wicker. Associate Editor of The yew York Times, visited Dartmouth for threedays in late January as Tucker Foundation Resident Fellow.

Professor Gaylord, former AcademicDirector of Alumni College, is a memberof the English Department.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureSailing Dreams and Random Thoughts

March 1973 By JAMES H. OLSTAD '70 -

Feature

FeatureTHE ACRONYM SYNDROME

March 1973 By JAMES L. FARLEY '42 -

Feature

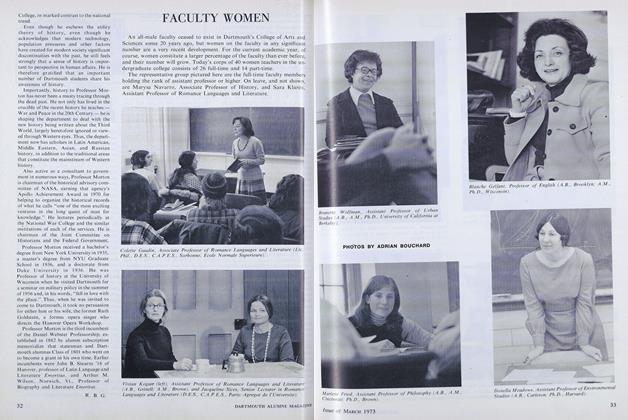

FeatureFACULTY WOMEN

March 1973 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERGRADUATE JOURNAL

March 1973 -

Article

ArticleBrautigan's Search for Reality

March 1973 By RICHARD D. CARYOLTH '73 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Days—60 Years Ago

March 1973 By Leslie W. Leavitt '16

Features

-

Feature

FeatureVincent Starzinger Professor of Government 1,000 miles in o single scull

January 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThao Dinh Vo '91

March 1993 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryINDIAN SYMBOL FELT

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Feature

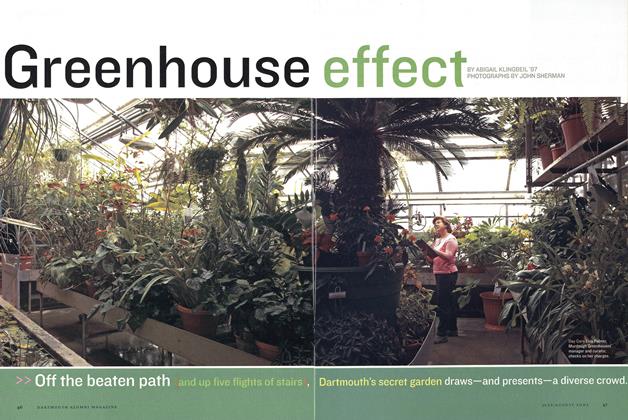

FeatureGreenhouse Effect

July/August 2005 By ABIGAIL KLINGBEIL ’97 -

Feature

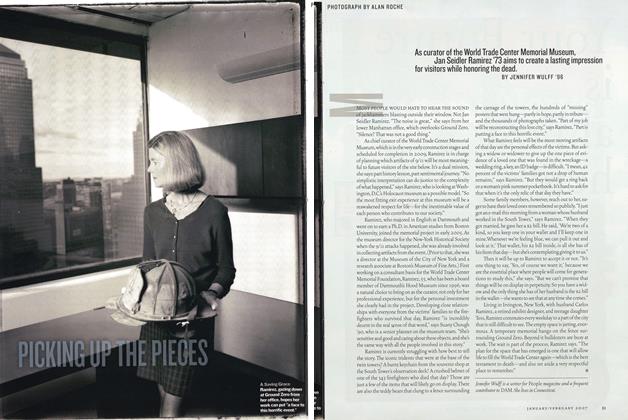

FeaturePicking Up the Pieces

Jan/Feb 2007 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

COVER STORY

COVER STORYTelevision’s Wonder Woman

MARCH | APRIL By Jennifer Wulff ’96