FROM the first Dartmouth has been a liberal arts college. It has been often said that the historic college is more concerned with men's lives than their livelihoods. And as far as I am concerned that is well so long as we do not lose sight of the fact that there is some relationship both backwards as well as forwards between leading a good life and the way a man keeps alive.

"The historic college has always insisted on its right and its duty to pursue the truth without let or hindrance from prejudice or any other interest and to make that truth known. And again as far as I am concerned that is well so long as we are sufficiently humble to grant to providence, and the next generation, the possibility that the truth of the day for us may not be an eternal verity - and also so long as this spirit of humility is not in practice carried clear across the spectrum of tolerance to the point where men of knowledge and good will become incapable of action and leave the world's doing either to those who don't know, or who don't care or, as in all too recent times, to those who do evil gladly. ...

"As you gradually discover for yourselves the things you care most about - and I hope for you they may be the right things - don't take them for granted. In all your learning get not only wisdom but also build the will and acquire the capacity for doing' something about those things which need doing. I personally care not very much whether your doing be in the public service or in the ranks of the citizenry. I do want very much that this generation of educated men of Dartmouth should 'be ye doers of the word, and not hearers only, deceiving your own selves.'

"And remember this: there is so little time."

From, President Dickey's first address to theundergraduates, at Dartmouth Night, November 9, 1945.

"Both for you who are returning to Dartmouth and you who are here for the first time, may I remind you that you are taking up three different, although closely intertwined, responsibilities: One, you are citizens of a community; two, you are the organic stuff of an institution; and three, your business here is learning....

"Let me remind you again that your business here is learning. All else is subsidiary; this is the 'why' you are here. Behind you are literally thousands of men who want to be here but cannot because you are here. You will find the pace stiffer, the purpose clearer. The College recognizes the 'right' of no man to be here, but after much effort and concern it has bet on each of you as being worthy to be here - that is, worthy of the business of learning. We know you can if you will. That is something, gentlemen, that is between you and yourself every single day of the days ahead. We will be with you - and good luck."

From President Diekey's first Convocationaddress, March II, 1946.

"For many of you this is your second going out from college into the world. Many of you already know from personal experience or observation something of the rewards and sacrifices which go with courage, fidelity, responsibility and humility - the counsels of virtue commonly given men about to enter the world of affairs. Without hesitation I give them to you again and I will but add two other senses which have always served men well in civil and civilized living. They are, first, a sense of proportion in all things, and secondly, a sense of timeliness at all times.

"Yours will be, I think, a world in which at least working answers must be found for the implications of expanding democracy and expanding government, nationally and internationally. I know not what these answers are, but I am sure they lie ahead, not behind. And I am sure of one thing more, these answers and the answer to your own happiness rest in large measure in your mastering the art and spirit of living with other men just as human - and inhuman - as you and I."

From President Dickey's first valedictory, tothe Class of 1946, June 1946.

"I hope that whatever else you have already learned in war or may learn here in peace, when the time comes you will leave college understanding two things about the world:

"First, that the world's troubles are your troubles even though the converse may often seem to you not to be true; and "Secondly, that the world's worst troubles come from within men and there is nothing wrong with the world that better human beings cannot fix."

Convocation Address, October 4, 1946.

"An introduction to humility, gentlemen, is a large part of any man's education. It is the surest solvent known for those two most persistent enemies of the educated man - pride and prejudice. Whether you are entering your first or your last term at Dartmouth, honest humility is a quality worth your cultivation and your respect. I have no formula for either teaching or learning humility. I suspect there is none of general application. But I can suggest this. True humility is a hard thing to spot in others. Here, as with so many other things, a good place to begin is with yourself. When you have acquired that discipline of self which brings you occasionally to a conscious mental stop, you will soon begin to recognize the presence of humility, or even better, the lack of it, in yourself. As those occasions multiply, they will become less self-conscious and, other things being equal, you are on the road to becoming a thoughtful person who has some chance of getting at the essential working truths of our daily lives."

Convocation address, October 5, 1947.

"The ultimate validity of these facilities, as of all others, must be seen and judged in relationship to the purpose and performance of Dartmouth as an undergraduate liberal arts institution where men live as well as study. At the heart of such an institution is the fact that it is a community - a condition of life in which all men share common experiences together. Today we do not have that condition at Dartmouth. One of the key principles to my mind in the educational philosophy of the College is that the common experience is still the tap-root of cooperative living. That principle is at the heart of the Great Issues course, where all seniors are given a common intellectual exposure to the large issues of their time in an effort to develop a greater sense of common public purpose on the part of all our men as they go out to the responsibilities of a free society."

Remarks at a meeting of regional chairmenfor the Hopkins War Memorial fund campaign, October 23, 1947.

"A year ago on this same occasion I suggested that an introduction to humility was a large part of any man's education. May I today suggest to you that an introduction to loyalty is also a large part of any man's education. Humility is an indispensable prerequisite to learning and wisdom. Loyalty is the temper in the steel of the true man; it is an essential ingredient of effectiveness in the affairs of men. And there is no better time than now and no better place than here for each of us to introduce himself to these two qualities of the truly educated man."

Convocation address, October 1, 1948.

"I want simply to call your attention to another aspect of human experience which seems to me to be ever more important both to individual usefulness and the possibility of carrying this civilization to a more worthy and mature reflection of all that is good in humankind. I refer to the capacity of men for cooperative action, that process which we call cooperation. ...

"The very uncommonplace international affairs of our time demonstrate how indispensable is the process of cooperation at the highest levels and in every phase of human affairs. Cooperation in all literal truth is the very fabric of the cohesiveness which we call by the word community. It matters not whether that community is the Dartmouth community which it is our privilege to fashion this year, or at the other end of the same spectrum, the world community whose fashioning is the business of all peoples."

Convocation address, September 21, 1949.

"I do believe there is a grace in the universe which stands with men who face front. I also believe that a man is helped in the hard business of facing front by his understanding why he faces what he does. ...

"The world's errors and evils are not new. A student of history finds their counterpart in every recorded society. What is new is not the evil in man, but the range of its opportunity and the immensity of its consequences. Within the last fifty years alone the destructive potentialities of human error and evil have been increased beyond calculation. ...

'We could discuss for a long time the bearing of these and other comparable factors on the task of education today. It is an aspect of the world we face which is still perceived but dimly and sometimes not at all. We cannot probe the vastness of that subject now, but I will venture this far: these are the frontiers where the decisive battles of education at every level of life must be waged in our time. Dim and grim as the outlook has been on these frontiers, there have been happenings which seem to me to say that the way ahead is still open and that if you must fight, the cause can be worthy of your best."

Convocation address, September 27, 1950.

"The College has a responsibility for all educational influences connected with it and it cannot look with complacence upon any undesirable external educational influence on the campus. This College neither teaches nor practices religious or racial prejudice and I do not believe that it can for long permit certain national fraternities through their charter provisions or national policies to impose prejudice on Dartmouth men in the free selection of their fraternal associates. I want to be very clear that I am opposed to any suggestion that the chapters must or should take any man whom they do not themselves want as a member; but I am also very clear that I do not think it a healthy educational influence to have Dartmouth students forbidden from 'taking in' respected Dartmouth friends because of the racial or religious prejudices of a remote national fraternity charter or policy. I personally simply want the practical assurance that the undergraduates in Dartmouth's fraternities are free to take or to reject any eligible Dartmouth student on the basis of the undergraduates' own preferences and prejudices rather than some one else's."

From a statement for an InterfraternityCouncil booklet, March 1951.

"Perhaps the biggest lie and the most dangerous concept contending for men's minds today is the dogma of little men that all is understood which needs to be understood. It is not just point-making in argument to assert that our faith and our experience are one in denying the validity of any such ultimate arrogance. There is not a man in the far-flung fellowship of Dartmouth who today does not possess, as common knowledge, understanding of some things as to which the greatest intellects of the past were in error or ignorant. The great truth which all history nurtures is that men have never yet had all the right answers.

"If we are right about that, the pursuit of truth at every level of life remains the prime business of our free society. For that task the free mind in men of good will remains the supreme asset of a peaceful and truth-loving people."

Alumni Fund statement, April 1951.

"Here on Hanover Plain, in the sight of Dartmouth Row, and in the surrounding North Country, a man learns something of beauty almost in spite of himself.

"In this community of teachers and scholars and in the recorded presence of all that the mind of man has ever known, you have learned that he who scoffs at intellect and knowledge is one who least understands how little we know.

"You have seen in our time, as in every time, the futility, indeed the eventual evil of seeking to enforce either the acceptance or the rejection of ideas by the suppression of ideas.

"You have witnessed on the campus and abroad in the land the living truth of the words in which Mr. Justice Holmes reminded us that 'the epithets you apply to the whole of things ... are merely judgments of yourself.' "

Valedictory to the Class of 1951, June 17, 1951.

"I trust it is manifest to you that college is not the point in a man's growth where he first learns of the main moral boundaries which exist in this society. If the family, school and church have not provided a boy with that knowledge, his presence here as a young man is a sad mistake. Let us be clear about it, the fewer such men we equip with the powers and appurtenances of higher education, the better off we'll all be.

"But, gentlemen, this is the point in any young man's life where he begins in earnest to learn the weight of things for himself. The burdens of responsibility now shift rapidly from the shoulders of your parents and teachers to your own back. Whether it be at college, at work or at war, the central moral lesson taught in the curriculum of life at this stage in growth is that free man is answerable because he is free. That, I think, is the root meaning of responsibility. You have heard that experience is the best teacher. In this respect it is the only teacher. The terrifying truth is that young men learn responsibility by being permitted some opportunity to be irresponsible. Your task from here on is to use your opportunities of choice to build into the fibre of your experience the strength of moral choices."

Convocation address, September 26, 1951.

"What is the central need of human society today? In the last five years the central need to me is to bring into better balance the utter physical power which men possess as compared with the moral and political control of that power. ...

"What is the principal factor involved in getting a better balance between physical power and its moral and political control? I believe the central factor in the problem is the time factor. ... We are now confronted with the awful task of so accelerating the development of political and moral controls in our international relations that the sudden acquisition of this new power will not make the international mistakes and evils of our day final and irrevocable in contrast to the situation which has prevailed up to now in the conflicts of our world.

"You ask, what is the hope? I suggest this: the time factor in human affairs is not absolute; it is relative to the will and the capacity of men to serve the public good. This is where it seems to me the liberal arts college and the Bar come into focus on the problem. Leadership is the counter to the time factor in any human problem. The college seeks to create the will and the capacity for such leadership; the Bar probably provides the greatest opportunity for the exercise of such leadership in the home communities where the true strength of America has always rested."

Address at the annual dinner of the Vermont Bar Association, October 3, 1951.

"The point here is that the business of being a gentleman has a deep and direct bearing on whether you ever become a liberally educated man. This is the real reason, I suggest, why this College and any college worthy of service in the liberating arts must ask that those who seek her privileges shall honor and practice the manners of gentlemen. It is not merely, as is so often assumed, that a gentleman is less trouble to have around, although I assure you that that is not an inconsiderable item itself in the eyes of the teacher and his administrative aides; rather, it is the fact that there is a profound working affinity in the liberating arts between those two honored words of the ancient tribute - 'a gentleman and a scholar.' "

Convocation address, September 24, 1952.

"I think it is hardly necessary to more than say that Dartmouth believes in intercollegiate sports; we believe in the value of the will to win in honorable competition; we want good teams, but we know that our fortunes will vary from year to year and from sport to sport in healthy cycles so long as, and only so long as, our teams and the teams we meet are subordinate activities in the service of the purpose of institutions of higher education."

Talk to the student body over StationWDBS, January 10, 1952.

I have said that one of the dangers in discussing this subject [the Communist problem] is that it inevitably gives a negative and distorted notion of higher education. Let me try to avoid at least something of this danger by beginning with a word about the nature of the business of these enterprises which we call colleges and universities. I suggest to you that after all the verbiage is stripped away, the essential function of this business is the maintenance of a free and honest marke place for the exposition, exchange and evaluation of ideas. That gentlemen, to put it somewhat inelegantly, is 'the guts of the business.'

"I have learned from experience that you cannot take for granted that everyone understands the nature of the business of higher education. To put it concretely, it is very hard for most people who are not engaged in the daily work of higher education to realize that the famous statement attributed to Voltaire, 'I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it,' is not merely some lofty ideal of life so far as higher education is concerned, but that in this kind of enterprise those words express what in a commercial business is known as 'the profit principle.' A commercial business goes 'bust' when men lose sight of the profit principle or serve it poorly, and in higher education a college is on the road to bankruptcy when it ceases to honor in either word or practice the principles by which truth is ceaselessly sought through the exposition, exchange and evaluation of ideas by men of honest and independent minds.

"Having said that the business of a college is different from other businesses and that it is governed by different principles, it needs to be said with equal emphasis that these educational enterprises are like all other human undertakings in at least one important respect—they are run by men. Let us be clear about it - higher education is not immune to error and even evil. It has its share of fools and knaves. But, taking into account the nature of its business, the maintenance of a free market for the development and examination of ideas, this business has over the long haul perhaps the best record on earth for exposing and purging any form of human fault. That, gentlemen, I suggest is the great strength, it is, indeed, the indispensable service which higher education renders the free society of which it is a part. Anything which weakens that strength and impairs that service will surely and quickly poison the climate of any free society."

Talk to the student body over StationWDBS, March 13, 1953.

"I do charge you to remember that the power which flows from higher education is not automatically beneficent. By bringing within your reach the better answers which other men need in their daily lives, Dartmouth has endowed each of you with some possibility of power far beyond the common lot. I am not clear myself that power inevitably corrupts, but that it will do so unless it is constantly questioned by its holder I think I know full well.

"In the larger context, most of you are destined to be the stuff of a nation which once again faces the most ancient dilemma of statecraft: how to be strong enough to be free and yet remain decent enough to be long strong?"

Valedictory to the Class of 1953, June 14,

"I speak of maturity as that ultimate self-discipline which rules a free man. It, too, like the power of thought, must be won by every man for himself. It is a quality born of growth and as no other, it measures at every stage the fulfillment of an individual as a human creature regardless of all else. It embraces the intellect, but it is much more. It cushions and beds the sharp edges and brittleness of thought in humility, loyalty, cooperation, good manners and the moral sensitivity of a good man. Maturity in man at his highest is not a substitute for the substantive works of reason and faith but is, I think, that condition of man in which those two sources of power prosper best. ...

"Maturity is one of those prime personal qualities which seems to have its close counterpart in the national character of a people. Nothing within the power of man is more important today than the measure of maturity which Americans contribute to their national character. The time factor is so pressing that the outcome cannot be totally assigned to you either in rhetoric or reality, but I do believe that you will have the really great experience of crossing the threshold of maturity in the company of your country."

Convocation address, September 21953.

"Important and reassuring as it surely is that life's best teacher, experience, vouches for the liberal arts as the richest repository of earthly understanding and joy, I believe we do only very partial justice to our case if we rest it primarily on this passive view of the liberal arts as being merely arts appropriate to a free man. This may have been an adequate view of the matter in societies where the destiny of man in freedom, or in slavery, or in animal-like drudgery, was largely determined by the chance of birth. But that day is gone in our land and it is a day on which the sun will surely set in every land where the idea of human justice and freedom is known even to one as it must some day be known to everyone.

"In a free land the never-ending frontier of freedom's forward thrust is each man's mind. I suggest to you, and I avow for myself, that in our American society it behooves institutions of the liberal learning to take a dynamic view of their mission. Ours is the task to free as well as to nourish men's minds. This is why, as I have sought to understand the nature of Dartmouth's obligation to human society, I have come increasingly to think of our commitment of purpose as being to the liberating arts rather than just the liberal arts. It is the active, liberating quality of these arts, I believe, that makes them the 'best bet' for Dartmouth's purposes. ...

"The motto of the State of New Hampshire reads: 'Live Free or Die,' and as you today go forward in the liberating arts I remind you that for us those words are not merely a political admonition; they are also a statement of fact - 'Live Free or Die' is the law of intellectual life."

Convocation address, June 13, 1954.

"Without attempting here the impossibility of conclusive proof, I suggest that the American liberal arts college (including the church colleges) can find a significant, even unique, mission in the duality of its historic purpose: to see men made whole in both competence and conscience. Is there any other institution at the highest level of organized educational activity that is committed explicitly by its history and by its program to these twin goals?

"This is not to say that our great professional and technical institutions or the graduate schools of arts and sciences are something less than the liberal arts college, but rather that they have set themselves a different task - the mission of developing a special competence. Nor am I unaware that these institutions and the liberal arts colleges are borrowing more and more from each other in approaching a closer integration of all higher education. But my point is that the historic liberal arts college has had a unique mission and that this mission has reality and validity today. ...

"A moral purpose exists for its own sake or it is nothing. I have no thought of propping it up here with extraneous arguments. I merely offer the observation that there seems to be a significant natural affinity between the liberating arts and an educational enterprise committed to the dual purpose of competence and conscience. You might call it reciprocal invigoration.

"To create the power of competence without creating a corresponding sense of moral direction to guide the use of that power is bad education."

From "Conscience and the Undergraduate" in the April 1955 Atlantic Monthly.

"Today the historic, independent college either has its heart set on retaining a margin of excellence or it is on the way down. This is the law of survival in the expanding world of higher education that has been created within our lifetime by the power of taxation.

"The great public universities are not the enemy of the private colleges, but they are daily providing opportunities for both students and teachers by which the margins of private education will be tested. If those margins of purpose and performance disappear, the private college will become a finishing school for men in a society that has long since lost interest in such an enterprise."

Dartmouth Alumni Fund statement, June 1955.

"If you will permit one more word about the experience of 'going to college' that is now behind you, it is this: education is nothing unless it is used. Whatever else you fool yourself about, don't fool yourself about this - after all the courses, good and poor, after all the honors and the flunks, after all else in college that was or was not just right, after all this is behind you, as now it is, the only thing that is decisive about any college education is the follow-through. No college education, literally none, is ever either so good or so poor that this is not true. Your sense of self-interest will take good care of the rest, but the quality of your liberation as a brother of man and as a son of God will be seen in your daily follow-through on those things that even the least accomplished among us must now know is within his grasp as a graduate of Dartmouth."

Valedictory to the Class of 1955, June 12,1955.

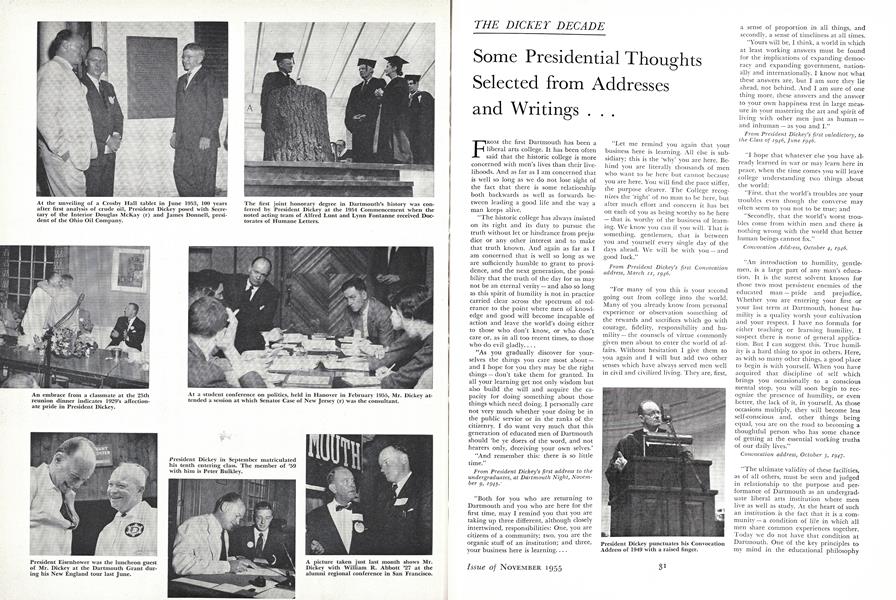

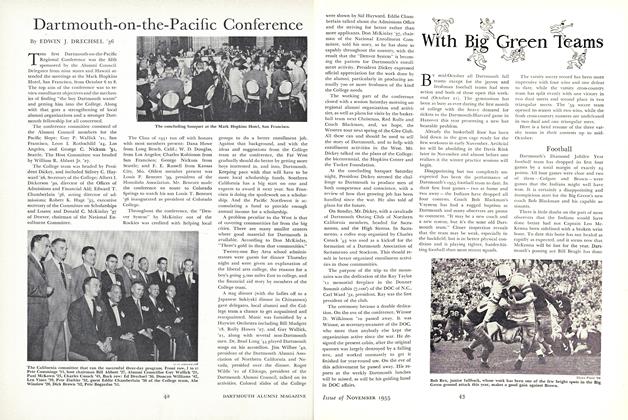

President Dickey punctuates his Convocation Address of 1949 with a raised finger.

Informal occasions for speaking are also numberous in the life of a college president. Above, Mr. Dickey is shown (left) at the Dartmouth Night observance in 1949, and (right) at a party held by the residents of Cutter Hall shortly before the Christmas vacation last December.

Informal occasions for speaking are also numberous in the life of a college president. Above, Mr. Dickey is shown (left) at the Dartmouth Night observance in 1949, and (right) at a party held by the residents of Cutter Hall shortly before the Christmas vacation last December.

The President just before starting a "fireside chat" to students over WDBS

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureTHE REASONS Behind Corporate Gifts to Dartmouth

November 1955 -

Feature

FeatureThe Convocation Address

November 1955 -

Feature

FeatureA Review of Major College Events

November 1955 -

Feature

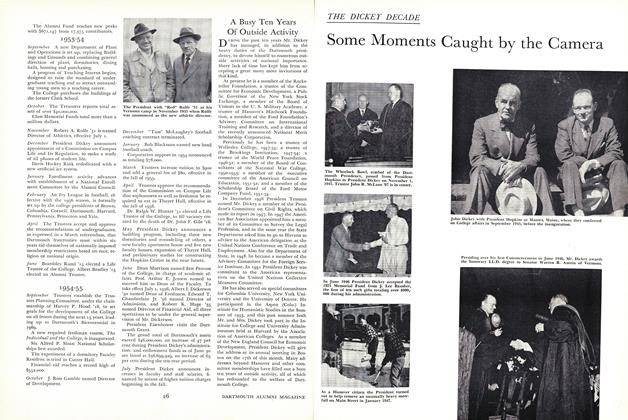

FeatureSome Moments Caught by the Camera

November 1955 -

Article

ArticleFootball

November 1955 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1918

November 1955 By ERNEST H. EARLEY, W. CURTIS GLOVER, RICHARD P. WHITE

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTrustees and Alumni Council Meet

FEBRUARY 1973 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryExcerpts from Beverly Sills' Commencement Address

June • 1985 -

Feature

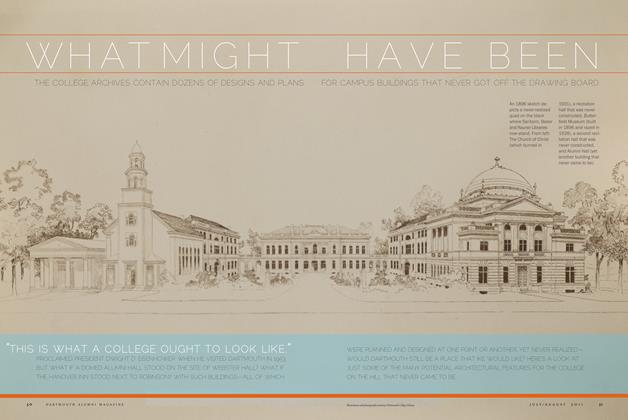

FeatureWhat Might Have Been

July/August 2011 -

Feature

FeatureLessons from the Past

OCTOBER, 1908 By Allen A. Ryan '66 -

Feature

FeatureSoldiers As Policy Makers

February 1951 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Feature

FeatureThe Mold

SEPTEMBER 1996 By Warren Cook '67